I met the architect Rasa Chmieliauskaitė and the art historian and curator Justinas Kalinauskas, the founders of the ArchiTextura LAB non-visual architecture cognitive research and creative platform, in the exhibition space of the Kaunas Artists’ House. Rasa was carefully winding paper-thin strips from a roll of wood chips, and then attaching them to a wooden frame that was built by Justinas. They were preparing for the final highlights of the forthcoming exhibition ‘ArchiTextura: Unchanged & Evolving’. In their creative and cosy space, we talked about the installation of the exhibition, which was born out of careful research in Lithuania and Japan.

In 2022 the ArchiTextura LAB team started their collaboration with the Japanese artist and architect Tomomi Homma (本間智美). In the same year, an artists’ residency took place in Kaunas, where both artists explored traditional Lithuanian architecture. At the end of the residency, they presented the exhibition of tactile architecture ‘Invisible & Similar’. In 2023, this intercultural residency moved to Japan, where they also conducted artistic research and collaborated with people who were blind or partially sighted. The result of this residency was the first part of the exhibition ‘ArchiTextura: Unchanged & Evolving’ in Kobe. It invited visitors to explore new non-visual and alternative ways to perceive architecture, and to look at the similarities and differences between traditional Lithuanian and Japanese architecture, by finding a universal architectural language in both countries. The second part of the exhibition has already arrived at Kaunas Artists’ House, and is open to visitors who want to experience, touch, see, lie down on, and rest in the installation, until 4 January 2024.

ArchiTextura: Unchanged & Evolving, Kaunas Artists’ House, 2023. Photo: Vytis Mantrimavičius

Agnė Sadauskaitė: Rasa, you are an architect. Justinas, you are an art historian. You met at a crossroads of your professional interests, and together you are developing projects in architectural research. When and how did you start working together?

Rasa Chmieliauskaitė: I was a practising architect, and Justinas worked with architecture from a methodological perspective as a researcher. When I came back after finishing my architecture studies in Japan, I started to look for new activities. Justinas and I met and found common ground between us. He was interested in architecture, but usually worked with artist performances, organised happenings, and experimental theatre projects. I worked in architecture studios, became involved with Ekskursas [an architectural tour platform in Kaunas] and started developing the TeKA cultural research platform of rivers and other projects. Then I began to think about it: what part of my life belongs to architecture as a creative ambition? Just after I asked myself this question, that is, what aspects of and tendencies in professional work limit and deprive architecture as a creative activity the most, the first ArchiTextura project, called ‘Invisible Architecture’, was born. My intuition and architectural experience helped me lead the first projects, while Justinas brought in work settings and methods.

Justinas Kalinauskas: In the first joint projects, I prepared the methodological basis, an educational programme, and a qualitative research plan. I started working on the projects on the academic side, but later I also became more involved in the creative process. For example, our second project on the topic of non-visual architecture was the audio album ‘ECHOtektūra’, for which I created the methodological basis, outlined the goals and aspirations, and helped to maintain a coherent creative process. The artistic part was taken care of by Rasa, and the composer and sound artist Arnas Mikalkėnas.

ArchiTextura: Unchanged & Evolving, Kaunas Artists’ House, 2023. Photo: Vytis Mantrimavičius

ArchiTextura: Unchanged & Evolving, Kaunas Artists’ House, 2023. Photo: Vytis Mantrimavičius

AS: The projects and accompanying exhibitions of ArchiTextura LAB are unconventional: by collaborating with people who are blind or partially sighted, you explore the non-visual cognition of architecture. In 2022, another thread appeared in the project alongside these points, that is, research into traditional architecture in Lithuania and Japan. Was it the planned long-term course of the project, or did the initial activities dictate the next phases?

RC: ArchiTextura LAB has become the name under which we prepare all our architectural research, although the name was born after the first projects. At the beginning, everything revolved around ‘Invisible Architecture’. When we started the first project, it seemed to me that the closest thing to the non-visual cognition of architecture was the touch. However, in the process, it turned out that it was actually sound, which was most accessible, and the very first source of information that could be felt in a space or an architectural object. This is how another idea for ‘ECHOtektūra’ was born naturally from the project. Later, we developed projects in partnership with ‘Kaunas 2022’ for three years: we not only conducted research, but after gathering enough theoretical baggage, we applied it in practice and created a pavilion.

I should note that over the years, some of these activities were planned in advance, but some emerged in response to various processes, questions that arose while working, or answers that were found. In fact, in the first project, I really wanted to talk about contemporary architecture, because it is the most painful topic: it shapes the environment, it is an actuality, a cultural discourse, which is often presented only through visual manipulations, through condensed, subjective visualisations that are frozen in the moment.

JK: This project aims to reconsider what the phenomenon of architecture is, and to understand whether it is universal and overcomes the cultural distance, in this case, between Lithuania and Japan. Organised space is a very rich and interesting world, which contains an inexhaustible, conceptual, multi-layered charge, so it is necessary to expand the understanding of what architecture is, and where its cultural and semantic boundaries are, especially since in recent years, physical space has been increasingly migrating to the virtual environment. It is disappointing that only a very narrow circle of architects delve into these topics and explore how architecture responds to a person’s world-view, influences the mental state, gives meaning to existence, and represents community interactions. All these questions are undoubtedly important and resonate among people in different countries.

ArchiTextura: Unchanged & Evolving, Kaunas Artists’ House, 2023. Photo: Vytis Mantrimavičius

AS: Although the initial goal was to talk about contemporary architecture, you have recently given your full attention to researching traditional architecture. Tell me more about how this architectural topic appeared in your work.

RC: During discussions with Justinas, it became obvious that we cannot yet study contemporary architecture with people who are blind, because there is no context, and there is no broader understanding of architecture, how to read and evaluate it. Therefore, in the first project, we studied the five architectural styles that are most important in Lithuania, and discussed and interpreted them. Later, together with the participants, we created a dictionary of architectural knowledge, and learned how to read architecture in order to be able to discuss it. We followed a similar methodology in 2021 when we travelled around the regions with an educational programme. So in this project, in order to talk about intercultural architectural connections, we looked for something to begin with, a key that would open the door to the spatial experience of different cultures. That is why we started with traditional architecture, with the tradition of the development of the collective space that lasts for centuries and responds to both the authentic relationship with the environment and the social aspect. It is the architecture whose architect is the time, and whose client is the tribe.

JK: Sometimes the topic of traditional architecture sounds controversial in the Western world. I think it is unjustifiably attracted to the radical right. If you look more closely, traditional architecture is interesting primarily because it developed very slowly: from generation to generation, people improved the principles and methods they discovered, they had a lot of time to solve problems that arose in the process, and to figure out how building materials and structural solutions worked. At the same time, traditional architecture responds to our living environment and geographical area. No matter how big the world is, a person is conditioned by the collective social consciousness, the common historical and cultural experience, and the environment. Traditional architecture still affects our subconscious: how we feel in a specific space, how we understand it, and how we interact with it. We believe that these regularities are common to every human, so we tried to find a universal spatial grammar that allows members of different cultures to communicate in the language of architecture, thus overcoming the language barrier. And indeed, we started a dialogue by talking about spatial issues. It is much more difficult to overcome the language barrier.

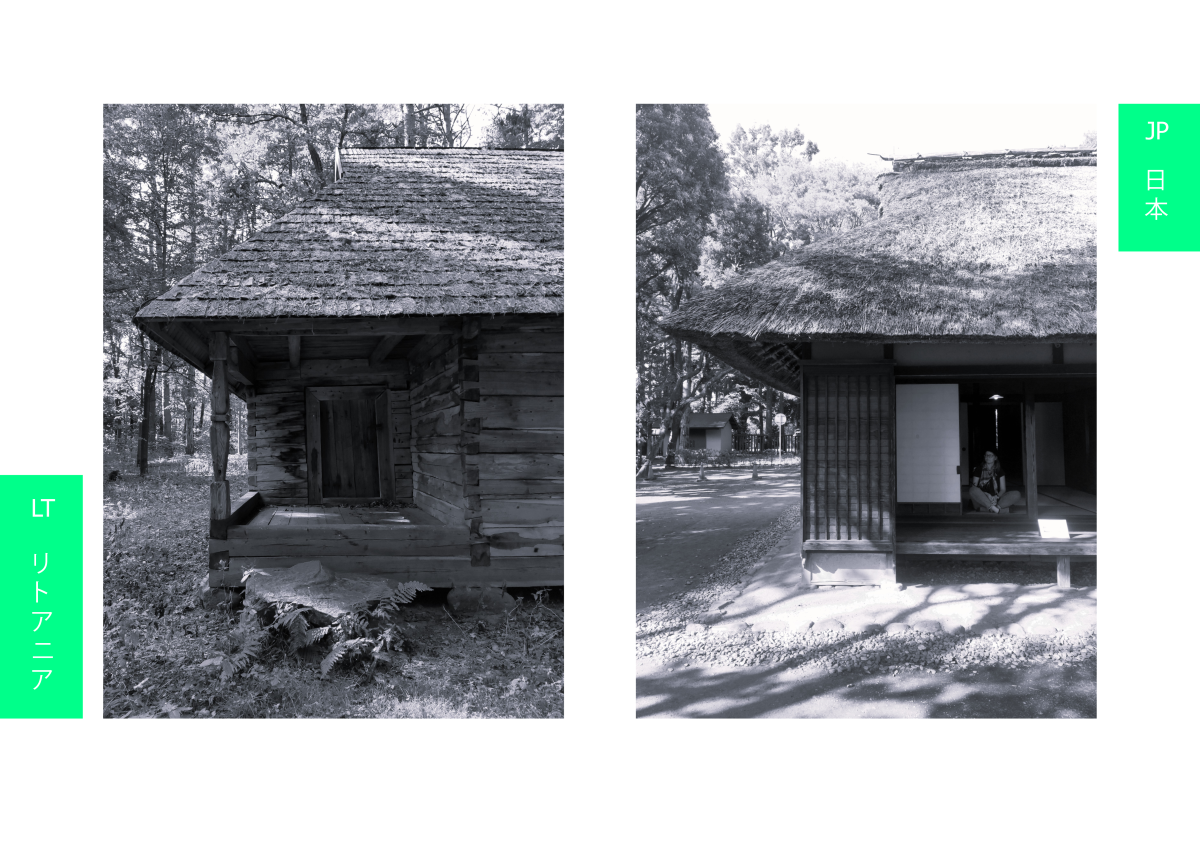

Lithuanian and Japanese architecture. Photo: ArchiTextura LAB archive

Lithuanian and Japanese architecture. Photo: ArchiTextura LAB archive

AS: Why did you choose to collaborate with Japanese artists?

RC: I studied in Japan, had some acquaintances there, and had quite a few insights about the visual similarities of the architecture. It was interesting to explore what was behind it. Other countries in Southwest Asia are not as similar to Lithuania as Japan, for they have a different architectural language and logic.

JK: In collaboration with Japanese artists, we tried to answer the question whether we read architecture similarly, and if so, whether there is something deeper, beyond the culturally embedded architectural character. The form of the exhibition was born from the search for commonality. As Rasa mentioned, there is a visual aesthetic similarity between the traditional environments of Lithuania and Japan, which, no matter how imaginative it may be, is probably accidental. We also found similarities in the use of materials and structural solutions. We cannot say why the traditional architecture of the east Baltic region and Japan are so similar in morphology and the nature of the materials. The Japanese were also surprised by this. The similarity was probably caused by the similar relationships between prehistoric communities and their environment, the availability of widespread local building materials, the partly similar climate in Lithuania, and the extensive areas of forest in parts of Japan. Some decisions were probably influenced by pragmatic thinking about the household, the space, and the need to create shelter as simply and cheaply as possible. First, a roof is built as a shelter from precipitation, and only then are the walls built. All architecture begins with the roof.

Lithuanian and Japanese architecture. Photo: ArchiTextura LAB archive

AS: Even before you visited Japan, you noticed a lot of connections between the two countries. You have said that when visiting museum exhibitions and objects of traditional architecture that are still in active use, you noticed the similar architectural language in both countries. How did you manage to explore the non-visual aspect? What is the universal cognitive language connecting Lithuania and Japan?

JK: When it comes to the oldest traditional architecture in Lithuania and Japan, the composition of the space and the spatial logic are very similar. A building functions as a shelter from rain. Inside it there is an open-plan space, one large room, in the middle of which there is an open hearth. In the long run, a more technologically developed solution, that is, a stove, came into use in Lithuania. Meanwhile, in Japan, the use of an open fire lasted longer, migrating from one style to another, and is still common today. Even in some modern houses, the Japanese try to maintain this tradition: there is a covered niche sunk into the floor, which, when opened, reveals a sand-filled bottom and an open hearth. This is an interesting rudiment.

As for the later architecture of Japan, which formed during the peaceful Edo period (the 17th to the mid-19th century), a greater distance can be felt between Baltic and Japanese architecture. Although the building’s appearance and outline are similar from an aesthetic point of view, they interact with the environment differently. In Japan, the warm season is considered more. The architecture of the country is adapted for ventilation, it is not insulated, and the walls are hollow, covered with easily sliding screens that can be opened in various ways, thus opening up a view of the surroundings. Architecture in Lithuania, on the other hand, is primarily designed to survive the winter, and is focused on comfort and safety.

RC: Another difference is the relationship with the interior space. In traditional Japanese architecture, the interior serves as a piece of furniture with many functions. In Lithuanian architecture, furniture functions as separate elements.

JK: I would also mention the close interaction with pure matter, especially wood and clay. In the Japanese landscape, we would find clay houses, which are almost identical to our old clay houses. Moreover, the space formed by the roof frame is very similar. This became a starting point for us.

Lithuanian and Japanese architecture. Photo: ArchiTextura LAB archive

Lithuanian and Japanese architecture. Photo: ArchiTextura LAB archive

AS: I want to hear a little bit more about your artistic residency in Japan, where you spent the whole of November. The culmination of the residency was an exhibition in Kobe, together with the architect Tomomi Homma. The first part was presented there, and the second part is in the Kaunas Artists’ House. What separates and what connects these two parts?

JK: We were residents together with Tomomi in an artists’ ‘village’ on the outskirts of Kobe, at the foot of a mountain overlooking the city. That is where we developed the idea of the exhibition during the whole month of November. The exhibition of non-visual architecture is not an attempt to present Japan or Lithuania. Rather, the exhibition became a representation of our creative collaboration in physical form: the three of us talked a lot about topics of architecture, culture and traditions, tested various materials that we discovered together, conducted spatial experiments, and gave a meaning to this dialogue in the exhibition. But of course, getting to know the country and comparing it with Lithuania had a big impact. During both the residency and the month-long expedition to traditional towns and villages in Japan, Rasa and I greatly expanded our understanding of Japan, even though it was not our first visit to the country.

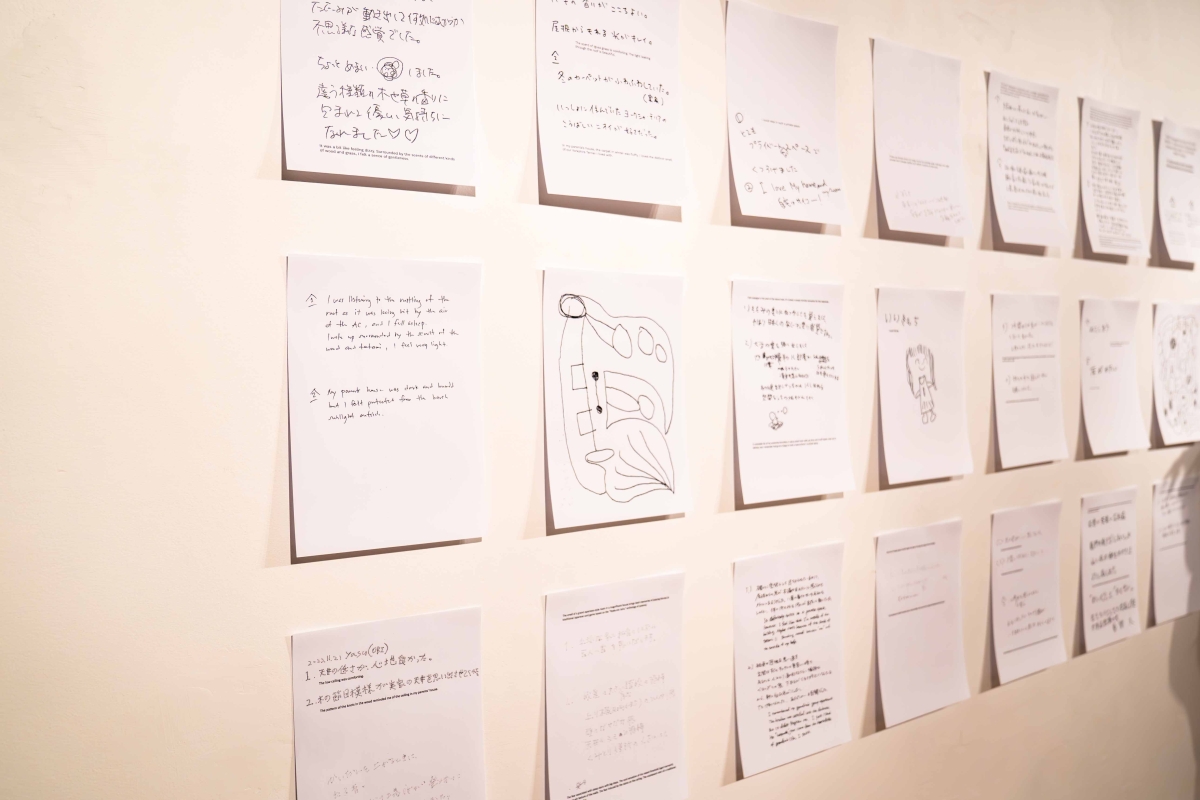

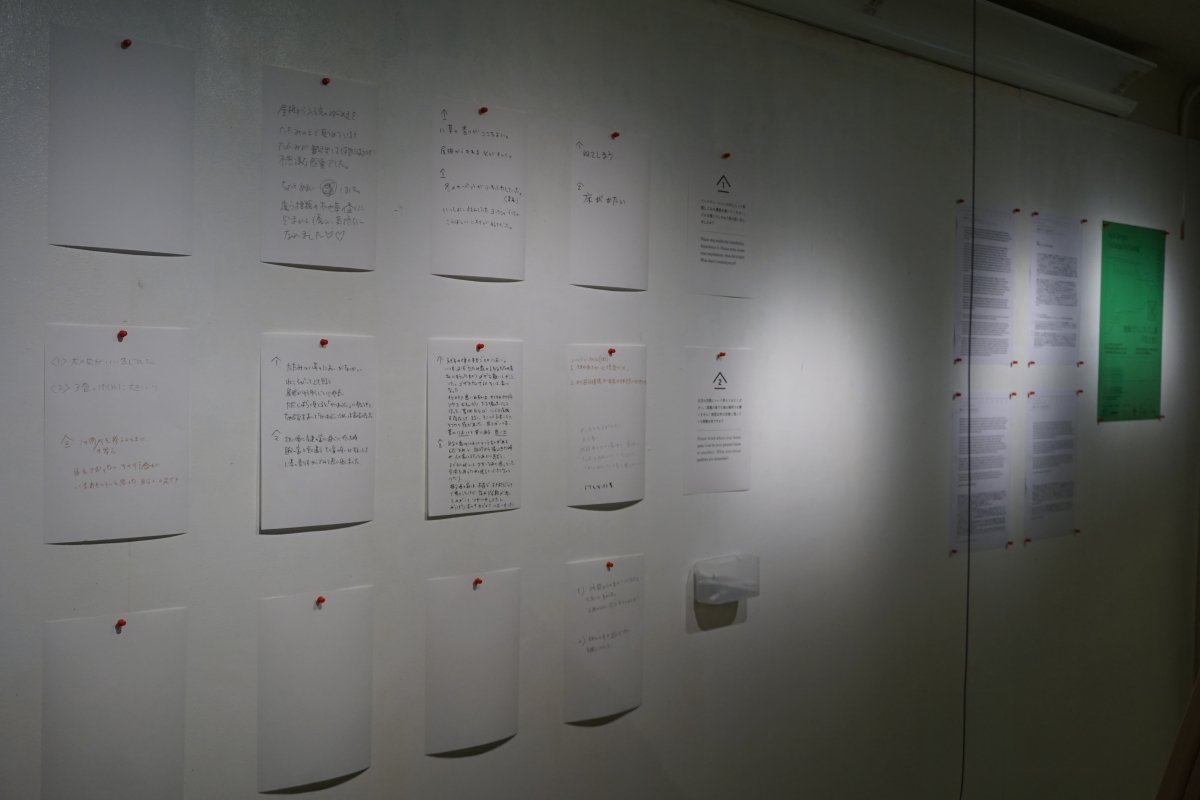

RC: Our goal was to create spaces as similar as possible in exhibitions for both countries. Part of the exhibition is a questionnaire, where we ask visitors two questions. We collect the answers on white sheets of paper hung on the wall. The questions basically invite you to reflect on your personal non-visual relationship with the environment, both in the exhibition space and in other spaces (at home, at work, in the city). The essence of architecture is to provide a controlled space and a shelter from what is outside. As Justinas has already mentioned, first there was a roof and a floor on the ground: so in the exhibition we also create a space of archaic refined architecture, a roof and a floor. In Japan, tatami (traditional woven grass flooring) played one of the most important roles in the exhibition: it is well-recognised there, although it is nowadays used less and less in practice.

JK: The tatami floor is a cultural, social, and, of course, architectural symbol that has an undeniable semantic load in Japanese society, because, regardless of your social status, you have the same tactile, comfortable relationship with the floor. For many Japanese, tatami flooring immediately draws a link with certain social practices, an attribute of community consolidation. However, we decided not to install a tatami floor in the Lithuanian version of the exhibition, because the relationship between such a space and the visitors to the exhibition which is usual in Japan would not be established here. It would be an exotic element, but it would not have a code system recognisable to visitors. In Kaunas, we presented a different solution: we used linen bedding, which inspired many of our childhood experiences.

RC: Tatami is an architectural dimension, and the architecture was determined according to its size. For example, a room size equals six tatami. It is also a measure of wealth, a measure that has a physical expression.

Exhibition in Kobe, STUDIO Y3. Photo: ArchiTextura LAB archive

Exhibition in Kobe, STUDIO Y3. Photo: ArchiTextura LAB archive

Exhibition in Kobe, STUDIO Y3. Photo: ArchiTextura LAB archive

AS: You have mentioned the use of similar materials as one of the similarities between Japan and Lithuania. Do you use the same materials for both parts of the exhibition?

JK: Yes, we brought some ready-made material for the roof from Japan, Japanese cryptomeria wood chips. They form both a visual and a non-visual basis for the exhibition installation. The chip is very fragile due to the structure of the wood, and this fragility also creates an interesting effect: as the chips are light, they rustle in the wind, making an interesting sound. Perhaps the strongest impression is still left by the distinct smell of this tree, which is unfamiliar to Lithuanians.

RC: In the exhibition, of course, you can touch everything. It is important to mention that when we speak or present non-visual architecture, it does not mean that our projects and exhibitions do not have any visuals. That would be impossible. It is important to understand that even if an image is only a by-product of creation, you can choose to control it or not, but subconscious visual decisions still take place, so we choose to control the visual expression in advance, even when the main focus is sound, smell, texture and spatiality. When we are presenting a created object to visitors who can see the exhibition, the problem arises how to encourage them to experience other qualities, not only the visual one. We can’t just turn off our sight, and it’s not enough to close our eyes, because we’re talking about the main sense for receiving information. The solution is to change the material, or to present it in such an artistic form that visitors experience it in a new way. This is also the case with the wood used in the installation: we are used to the fact that wood is a strong, hard structural element; but here it is completely different, fragile and thin, like paper that lets the light flow through it. By giving the material an unexpected aspect, we can feel its different qualities.

ArchiTextura: Unchanged & Evolving, Kaunas Artists’ House, 2023. Photo: Vytis Mantrimavičius

AS: One of the most important parts of both your past projects and the most recent one is collaboration with people who are blind or partially sighted. You already have several years of experience of this kind of work in Lithuania, and you know and cooperate closely with community members. How was it working with people who are blind or partially sighted in Japan? You have to deal with the language barrier too.

RC: It was different, mainly because a translator was needed, but in Japan people courageously participate and get involved in activities. When working with people who are blind, we define the rules and methods that we use in the workshop. All the proposed methods were willingly used by the participants.

AS: What methods did you use to establish a dialogue?

JK: Our colleague Tomomi helped with the translation, but we know from experience that much of the context is lost in translation. Therefore, we tried to weave a dialogue through non-visual language: smell, sound and tactility. Many Japanese people know where Lithuania is, but they have no cultural understanding of the country, so we brought some Lithuanian smells, sounds and sensations to the workshop.

Workshop with the blind and partially sighted community in Kyoto. Photo: ArchiTextura LAB arch.

AS: What was the non-visual representation of Lithuania?

JK: We brought Lithuanian linen, pine shavings, and sounds and smells of the environment. For example, frankincense was one such scent, as in a certain sense it has shaped the traditional Lithuanian cultural environment, which consisted of a forest, a village, a house, and of course a church. When it comes to a church, frankincense and myrrh are strong symbolic scents of reference that linger for a long time in the memory. This ‘map of the senses’ is well understood by the Japanese, because their temples, both Shinto and Buddhist, are also associated with smells: smoke, incense and water. From the point of view of the traditional Lithuanian way of life, the church was one of the factors that shaped the environment. Although Lithuanians are a secular society today, certain cultural signs are still recognisable to us.

Of course, this introduction to cultural sensations was only the first part. The main goal of the workshop was to understand how people in Japan who are blind interact with the environment, where the obstacles are, and where the opportunities are, what the traditional environment means to them, and, most importantly, how the space reveals itself to the people who have perhaps the deepest direct relationship with it. In various projects, we developed a method that we called tactile photography, or, as Rasa called it, finger photography. It’s a piece of chalk paper stuck to a white piece of paper and folded in two. Using this chalk paper, you can touch surfaces of interest, and an impression of the touched surfaces remains inside this ‘tracing paper’, reminiscent of a real photograph. Rasa interestingly formulated this method: looking at such a photograph, all sighted people find themselves on the same level of perception as the blind, because they only see what the latter have touched. Nothing more and nothing less.

RC: This method has become a democratic way of sharing impressions. People who are blind or partially sighted can take pictures with cameras too, but when sighted people are shown the photographs they have made, they see more: colour, context and additional details. But maybe they also see less, because they don’t necessarily notice what the photographer actually wanted to capture. In other words, the experience level of these people is different.

JK: With this method of photography, we tried to bring together the experiences of people who are sighted and who are blind, to understand which spatial experiences are interesting to them. This is not always an easy answer. It is not uncommon for us to have a misconception about blind people that their other senses, like touch, are highly developed, and that they are experts on surfaces and materials. This is not always true, for these people are often told by their parents not to touch anything.

Workshop with the blind and partially sighted community in Kyoto. Photo: ArchiTextura LAB arch.

Workshop with the blind and partially sighted community in Kyoto. Photo: ArchiTextura LAB arch.

AS: Is that really true? I would have thought that people who are blind are always encouraged to explore their surroundings, for their own safety.

RC: I have noticed these trends while conducting research. For example, parents often forbid blind children to touch white walls in order not to damage them. Children are culturally taught not to touch ‘the environment’. Therefore, at the beginning, the workshops were difficult to organise and lead, as it was necessary to encourage the participants to explore surfaces. Some other things also required extra attention. In the first project we explored architectural styles, we went to a Baroque church and touched its marble. Everything seems beautiful, but if you don’t see the material, you touch old, uncleaned marble, and you feel dust and cobwebs … What kind of personal relationship is formed with Baroque?

JK: Sometimes people who are blind or partially sighted have preconceived notions that certain objects are warm, cold, tall, low, rough, slippery, etc, but they may never have touched them. They have heard others talking about them, but they have not had the opportunity to touch and see them. By the way, the word ‘see’ is a word used very commonly by people who are blind, because one can ‘see’ not only with the eyes, but also with the other senses. Using the method of tactile photography, they sometimes actually ‘see’ their surroundings from a whole new angle, especially when we ask them to tell us what they are touching. However, people are busy, and it is often a great luxury to stop and look carefully at the world. Whether you look with your eyes or by other means, it takes time and experience to immerse yourself in the environment. After all, many people who can see are indifferent to architecture (that is one of the reasons for the low expectations of the quality of the environment), because they do not know this language, do not understand its grammar, and do not have a dictionary. If you widen your horizons, the environment can be read like a book: we understand more and more with each new page read. Knowledge requires practice.

RC: Those who do not understand urban planning or architecture, can’t understand the content. We do different things in workshops with people who are blind, such as listening exercises, and passive and active echolocation. But we do it not because we want to teach them these skills, but to show that things they do every day can be used not only for safety or functional purposes, but also to enjoy the space, to explore it. Our aspirations are aesthetics, beauty, and creating such an environment. An acoustically or tactilely beautiful space is quite an unusual but very necessary concept.

ArchiTextura: Unchanged & Evolving, Kaunas Artists’ House, 2023. Photo: Vytis Mantrimavičius

AS: Listening to your stories, it is even more obvious that our spaces are not inclusive: they are created according to one accepted standard, that is, according to the needs of the majority, but not suitable for everybody who uses the environment. What do you think needs to change to make learning about architecture and the urban environment more inclusive for people who are blind and partially sighted?

RC: It is very important to emphasise that when creating an environment, the goal is not to single out one or several groups, and not to think about how to adapt the environment or object to them. Society is diverse, including in its needs. Not all our needs are visible, some are psychological. The space must be democratic, open and multi-layered. It is important to realise that there is a whole spectrum of different users. When working with people who are blind, we do not work for them, we work with them, we learn from them, and we notice that what is pleasant and aesthetic for them is also pleasant and aesthetic for the sighted. We are trying to find ways to turn the sighted from clinging to seeing things, and to encourage them to discover more layers of perception.

JK: You need to learn from the living environment. It is necessary to enrich the environment with the senses, but that does not mean that the only scenario is to load it with objects and overwhelm it with details. Architecture is an expensive and complex field, and at the same time it tends to change slowly, so the desire to constantly reconstruct space is not very sustainable. Perhaps one of the solutions could be not only aesthetic changes in architecture but also experiential changes, an attempt to remember the forgotten qualities of architecture and explore them more deeply, to give them new life and proper attention.

RC: Nowadays, the architect communicates directly with specific clients while working on the design, and tries to understand their wishes and needs, to create a functional and aesthetic space for them, whereas traditional architecture was the result of the work of thousands of architects and the expectations of thousands of clients. It was a long and slow process. The process can be witnessed in the architectural elements that have survived to this day, which now may look like decorative or stylistic details, but are functional or structural rudiments that have lost their original function but still have their own history and can help us read the evolution of architecture.

Because of some coincidence, Japanese and Lithuanian traditional architecture in one period developed with visually similar forms and materials. The reaction of isolated cultures to different environments has created forms that might suggest to us the existence of some kind of relationship between these cultures. And this hint encourages us to look for a common vocabulary to read the architecture, and then close our eyes and look at it again.

Translated from Lithuanian by Ugnė Andrijauskaitė