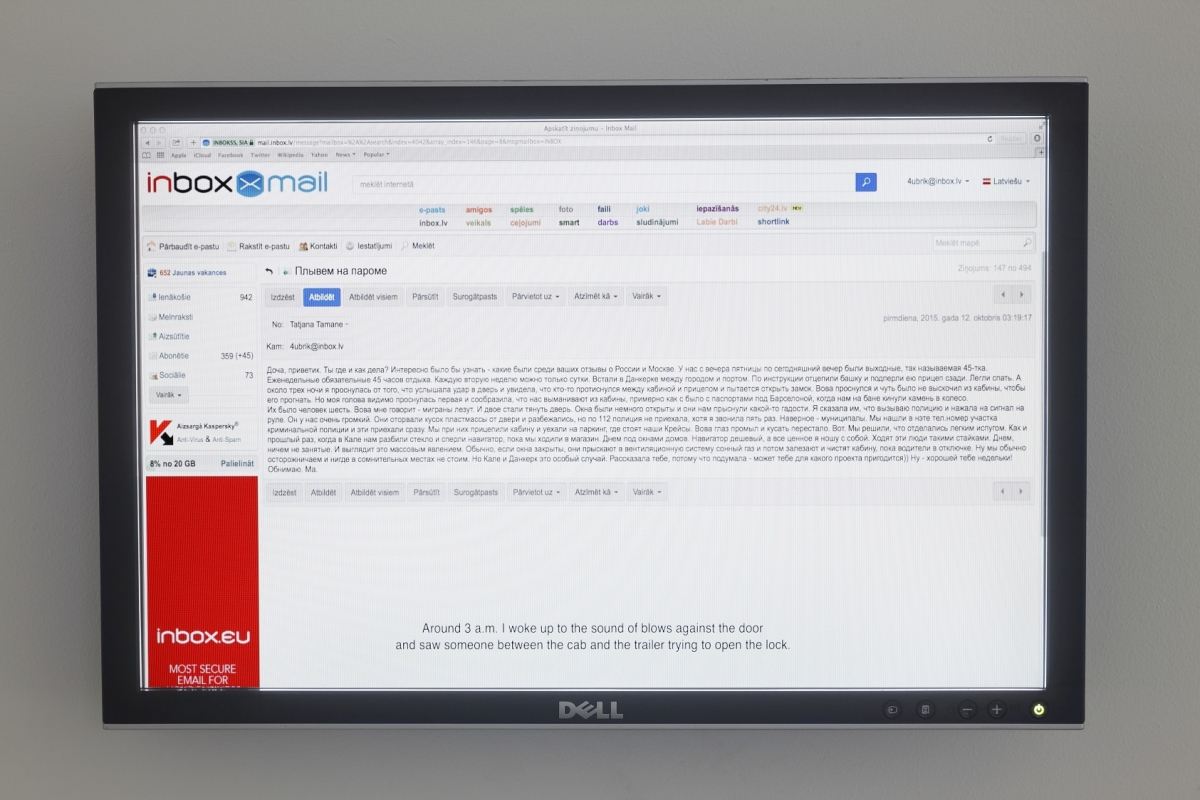

Diana Tamane, Message: 147 of 494, exhibition view, kim? Contemporary Art Centre, Riga, 2016. Photo: Ansis Starks

Interview with Diana Tamane

The work of artist Diana Tamane features private motifs – close-ups of her relatives (literally, as well as figuratively) and form a context for exploring socially significant subjects. The unusual depiction of relationships – ranging from a tender closeness to bewildering estrangement – indicates the ‘illnesses’ and hybrid forms of the post-Soviet society. Likewise, her exhibition Message: 147 of 494 a video documentation of Tamane’s mother’s journey through Europe driving containers, and subsequent contact with her daughter while the route, has developed from a personal narrative into a socio-critical commentary on women’s roles in the post-Soviet era, the value of family and social relationships in general, as well as self-identification. In Tamane’s photographs and video work, tension and emotional attachment are interwoven. Private aspects become collective in such a delicate and unobtrusive way that they lack any unpleasant didactics.

Diana Tamane was born in Riga. She graduated from Tartu Art College and received a master’s degree from LUCA School of Arts in Brussels. Tamane is currently studying at the HISK (Higher Institute for Fine Arts) in Belgium. Artist has had solo exhibitions in Belgium and Tartu, as well as several group exhibitions in Belgium, Russia, Turkey, Estonia and Latvia. Message: 147 of 494 is her first solo exhibition in Latvia. In 2016, she was awarded Friends of the S.M.A.K. Prize (Museum of Contemporary Art) in Ghent, and was selected as one of the upcoming young photographers for FOMU Foto Musuem’s magazine .tiff in Antwerp.

Her solo exhibition Message: 147 of 494 (2017) was on display at kim? Contemporary Art Centre until the 15th of January.

In your work, you have documented the self-portraits of women in your family and close-ups of their skin. Now at kim? we can be witnesses to a journey that is part of your mum’s regular work routine. How did your family become the subject of your art?

Often when I meet someone, I wonder where they come from or what their family is like. That is my natural interest.

Family is a small model of society and those relationships have an intense nature most of the time. Maybe that is why I am driven to that topic, because of the intensity and the complexity of it; some kind of concentrate to dilute.

Has your creative interest in your relatives altered the nature of your relationship with them?

I have collaborated with my family since 2009. Perhaps that fact has influenced and changed our relationships. But it is difficult to say in what way because relationships are always changing. And there are a lot of factors that influence these changes, like distance, time, etc.

Has your work enabled you to review what the notion of family means to you on a personal level and to add new and unusual content to it?

I want to approach this topic from different viewpoints. In general, I want to explore what the family album or portrait is, or what it can become. I want to see how much information I can extract from the one of my own family.

You once said in an interview that as far as art is concerned, you are interested in something that is broken and dysfunctional. Could you please expand on this?

Often my works are like leftovers or moments of failure. I try to do something, but then I fail.

It was the same with my movie On the road (2015), for example. I asked my mother to record her view from the truck for 6 hours non stop, from 12 midday to 6 in the evening. But she called me to inform me that it wasn’t possible and there was this tense conversation between us which happened to get recorded. In the end, I thought this conversation was much more significant to me than my initial idea.

I am also interested in awkward and tense moments of conflict in communication between people; moments of vulnerability. I find those things quite inspiring.

Diana Tamane, Message: 147 of 494, exhibition view, kim? Contemporary Art Centre, Riga, 2016. Photo: Ansis Starks

Diana Tamane, Message: 147 of 494, exhibition view, kim? Contemporary Art Centre, Riga, 2016. Photo: Ansis Starks

An important element of the exhibition Message: 147 of 494 is your mother’s male-dominated profession. Does that intensify the impact on the audience?

Yes, the fact that a woman could be a truck driver is quite exceptional. In Kreiss, the company where my mother works, there are about 2500 truck drivers out of which only 15 are women.

Is it important for you to address social issues in your work?

As much as I’m interested in the psychological aspect of relationships, I’m also interested in social and economical facets; it is interesting to see our past in relation to the present, and in relation to Western movements within Europe. Where and why do we move?

Having been away from Latvia for the last 10 years, I’ve moved around quite a lot, constantly adapting and learning new languages from different countries that I’ve been to, so the question of roots and routes has always been present for me.

I want to locate things in time, to be present, but at the same time it is of no less importance for me to deal with topics what were the same in the past and would remain the same in the future, topics like relationships, aging, love and death.

In the past, you have mentioned a particular interest in the feminine aspect, for example, the ties between the women in your family. Do you ground your work in feminist theory?

When talking about the portrait of my mum in the truck, for example, which also exhibited at kim?, I was inspired by the image of the ideal woman in Soviet propoganda posters. It was an image of a strong and resilient woman, who contributed to the communist society. Perhaps those images were still circulating during my mother’s childhood, of women in front of the factory, women driving tractors or cranes etc. So, I wanted to create this kind of image that was almost like an advertisement, keeping those Soviet posters in mind. Though, of course, the historical and economical context is very different now.

It would be easy to refer here to the feminist movement of the 1960s, which dealt with the private reflecting on the public, or highlighting the personal in order to reveal something political. But it is narrowing. At the end of the day, I would not label my work as being feminist or political, those terms are too strong. I don’t want people to read every work of mine only in that key. If I say it is feminist, the work will take on a kind of educative or dictative attitude, which I don’t want. I just want to share it, to tell the story, and to unwrap feelings.

Maybe you won’t say that when looking at my works, but I work quite intuitivelly, in a kind of flow that encompases energy, feelings and questions I have at the present moment. I am often looking for the climax moment within the quotidian. Banal, everyday actions are my resources.

Have you thought about the position of a female artist in today’s art world? What is your personal experience in relation to this?

I do not separate things by gender. I find this devision incredibly limiting.

What effect has your international experience and education had on your work?

I assume that because of my travelling experience, there was a natural transition from roots toward routes. My interest in roots (memory, identity), which is kind of looking back, extended toward routes (movements, migration, transportation), which I see as a view on the present. I am juxtaposing both and seeing what remains.

A few years ago, you said that you could be referred to as being an Estonian, Latvian or Belgian artist. Do you still feel the same about this statement?

Yes, because I am still living and working between these countries.

Diana Tamane, Message: 147 of 494, exhibition view, kim? Contemporary Art Centre, Riga, 2016. Photo: Ansis Starks

Diana Tamane, Message: 147 of 494, exhibition view, kim? Contemporary Art Centre, Riga, 2016. Photo: Ansis Starks

More about the artist: www.dianatamane.com