18 April

The deeper I delve into Paracelsus’ theory (though is it really a theory?), the more fascinating it seems to me. No, no, let’s not be stingy with words. This is no mere theory. It is a discovery. Yes, I have stumbled upon a terrible secret. I must reveal it. From now on, this will be my life’s purpose, a life that has been empty until now. As I contemplate this, I feel the presence of an invisible, immeasurable force beside me.1

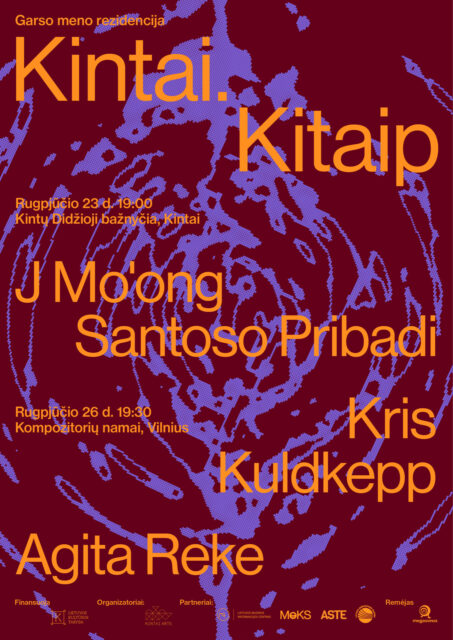

Contemporary art curators have long since moved beyond the role of mere art researchers. Increasingly, artists themselves are taking up curatorial work, while curatorial approaches are drifting away from analytical interpretations, often replaced by a kind of professional verbosity. Even the title of the 15th Baltic Triennial, a line from a poem, along with its curatorial approach, is devoid of theoretical methodology. The exhibition, curated by Tom Engels and Maya Tounta, invites visitors to experience it without expectations or preconceptions, much like the protagonist in the movie Groundhog Day, who, over time, is urged to surrender to the cycle of recurring time. This 1993 absurdist Hollywood film, directed by Harold Ramis, introduced a concept that has since entered the vernacular as a way to describe the monotonous existence familiar even to those who have not seen the film. In it, the cynical protagonist, a television meteorologist named Phil Connors, is condemned to relive the same dreary day in a small Pennsylvania town, paralleling a journey between the depths of suicidal despair and potential redemption, all without any guarantee that this worldly prophet and forecaster of futures will ever find a happily-ever-after in surrendering to fate. In a similar way, I attempt to surrender to this anti-chronological flow in the exhibition, yet despite the apparent absence of clearly defined themes or the decision to forgo titles and descriptions in the exhibition space, a sharp-witted dialogue is ever-present. As I wander through this space and time, an inescapable theme, time itself, begins to emerge, the very subject that has for ever intrigued poets, philosophers and free spirits alike.

Kaarel Kurismaa, “Light Column by the Entrance of the Tabasalu Secondary School”, 1986; “An Object for the Newly-Built City”, 1984; “An Object for Õismäe”, 1984. Mixed media. Installation view, 15th Baltic Triennial Same Day, Contemporary Art Centre (CAC) Vilnius, 2024. Photo: Kristien Daem

A poem by a Greek poet who wrote under the pseudonym Emerson, penned in New York in 1984, inspired the title of an exhibition half a century later, and now serves as a footnote in the curatorial text. The poem hints: ‘And only time can forget you,’ suggesting that perhaps only time cares, or only time affirms your existence. This sentiment resonates with Toine Horvers’ work Rolling 1, which filled the entire space of the Contemporary Art Centre during the Triennial’s opening weekend. Over the span of 15 hours and 25 minutes, ten drummers, in shifts, beat an uninterrupted rhythm guided by a score determined by the sky itself, mediated through a light sensor. However, it is not the fluid sound, impossible to ignore in the exhibition space, that the artist presents as the art itself, but rather, he designates the human being within time as the sculpture. This intention is vividly apparent in the form of the sound, which one wishes to listen to only until locating its source, the trembling hands of the musicians.

On the way to the main hall, I pass by the works of Michèle Graf and Selina Grüter from their series ‘Clock Mechanisms’. These metal gears turn, producing a clumsy mechanical melody, where the poetic primitiveness unites both theories of time, linear and cyclical. The unpredictable, untameable flow of time, and the monotonous cycle of time, converge in everyday witnesses: clocks. Their mechanisms, displayed without jewelled dials and hands, transform into bare music boxes or rattling fragments of time machines. As I step into the main exhibition, I cannot help but notice how the cycle of contemporary art has come full circle. Visitors to this liberating architecture of helplessness wandered these same spaces ten, perhaps even 20, years ago, during exhibitions curated by such eloquent curators as Raimundas Malašauskas. Just as in ancient Eastern wisdom, the world is recreated each moment with a slight, almost imperceptible margin of error, and after thousands of moments, everything essentially repeats. Amusingly, this recurrence happened after an inconspicuous renovation of the CAC building, whose exhibition halls seem frozen in time, with stable political structures that even construction crews cannot shake. The works scattered throughout the Contemporary Art Centre are like laconic comments in a space filled with air, though not necessarily with oxygen. The gas-filled spaces, unrestrained by the wit of the exhibition’s architect, are effortlessly yet precisely cut through by Elena Narbutaitė’s light observations. Meanwhile, the functional objects in the exhibition, sparse as they are, serve as additional literary footnotes from the curators. For example, a bench, a replica of a bench of the Renaissance Society of America, serves as yet another nod to all methodologies employed until now.

I began this article with a quote from ‘The Last Alchemist’, a short story by the lesser-known Greek writer Tasos Roussos. In the story, the protagonist, an orphan named Hieronymus, inherits a modestly comfortable sum after his parents’ death, enough to sustain a life without radical changes until the end. Thus, he becomes a living relic of the past, a small-time collector. Eventually, due to a fascination with one particular antique, he decides to dedicate his impotently comfortable life as a sentimental collector of trinkets to continuing the work of a famous alchemist who had discovered a panacea. After months of journaling, Hieronymus, a scribe of the past, dies as the last alchemist, either unaware of or unconsciously avoiding the responsibility of a noble work that could change the course of humanity. In a similar way, the curators of this triennial engage in a kind of alchemical documentation, poetically rewriting and subtly editing the archives of modern art, often pulling stories from the margins, preserving creative practices that did not fit into the professional art category during their creators’ lifetimes. This curatorial pursuit of truth sometimes feels like an attempt to justify unproductive nostalgia for days one never lived through, with the exhibition’s title acting as a reassurance that nothing is truly lost. But even if my interpretation is flawed, how can such a subjective phenomenon as time serve as a universal measure of reality? Naturally, the exhibition lacks chronology, and many of the works, which reveal themselves over time, are impossible to fully observe or listen to, whether lying on the floor, crouching near a speaker, or leaning against the walls. Such unwelcoming curatorial choices, grounded in decorative linguistic idiosyncrasies, resonate with me personally; yet as a viewer, I realise how ineffective they can be, or even appear to merely simulate activity.

Themes of the inevitability of choice and fate, which we shape ourselves, emerge strongly in the exhibition. We constantly make choices: to drink a glass of water or lemonade (Ian Law’s piece She’d), to marry or to live in solitude (Matthew Langan-Peck’s Red Light Dilemma 2), to stop or keep going. Even if we are choosing from only one-and-a-half options, because one is always lacking (the one we do not choose). In the exhibition, we repeatedly face the possibility of making the wrong decision in a sealed environment. Thus, we encounter ourselves safely and intentionally, allowing ourselves to be tamed by art, especially those parts of our identity that burst out unexpectedly and often alter our destiny. Take, for example, Andrius Arutiunian’s performance, where a staged taxi ride poetically navigates vintage uncertainty, connecting not only two cities, Vilnius and Yerevan, but also the author’s memories with the viewer’s present. Or Kevin Jerome Everson’s work The Return, where a professional novice pilot learns to fly a plane, rating how he feels every minute. These safe forms of adrenalin, impotently reaching for new heights, echo in the trophies of professional climbers summiting for the hundredth time, or in kart racers finishing yet another track. For thousands of years, we have debated time as the ultimate value, equally distributed to all, yet fast actions deceptively seem more valuable. In time, the true measure, meaningless pursuits depreciate, while meaning appreciates.

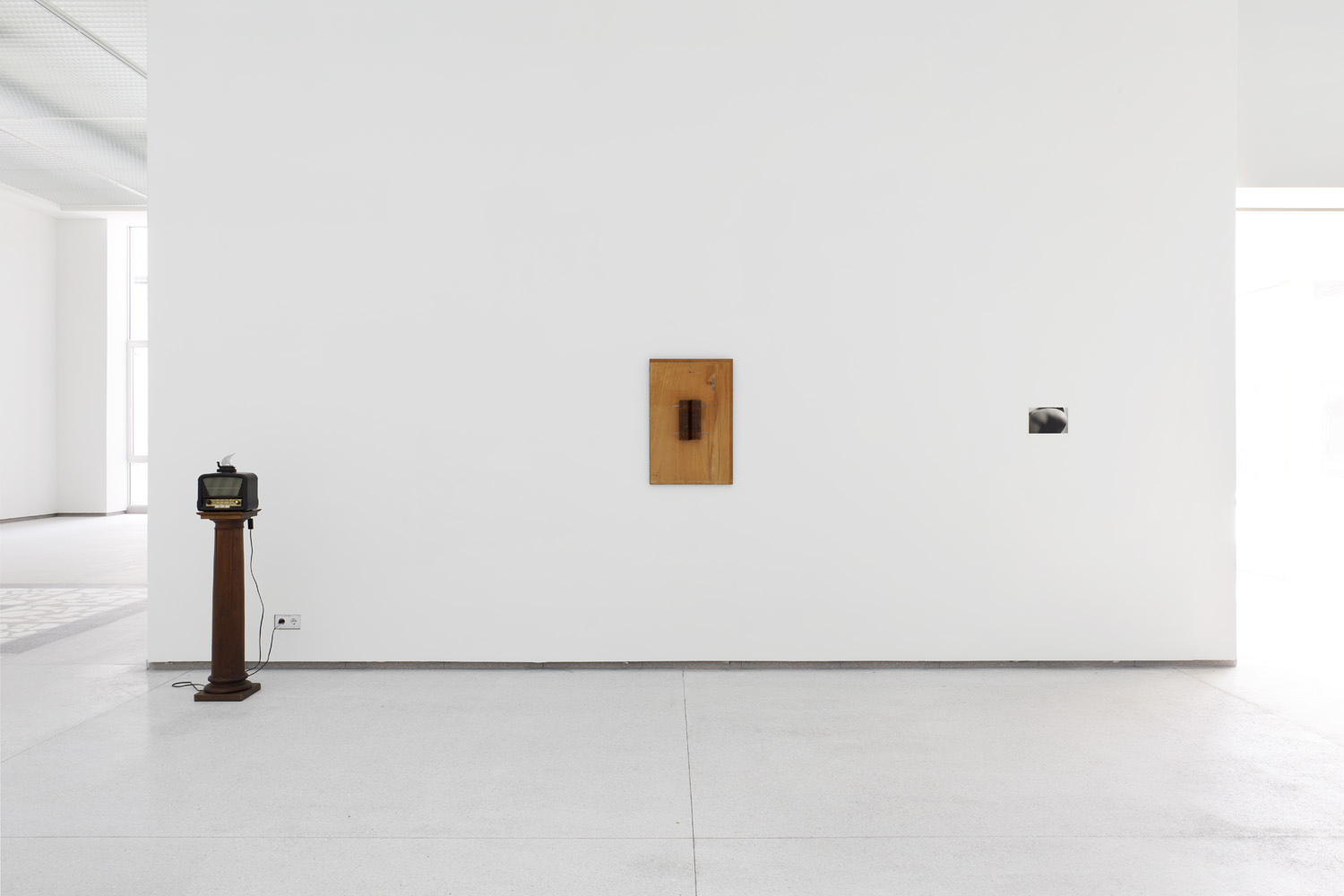

Kaarel Kurismaa, “Viking Radio”, 2001–2003. Ready-made, metal, plastic, electronics. Jiří Kovanda “Slip Away”, 1993. Wood, metal. Ian Law, “untitled”, 2020. Fibre based bromide print. Installation view, 15th Baltic Triennial Same Day, Contemporary Art Centre (CAC) Vilnius, 2024. Photo: Kristien Daem

The seemingly chaotic flow of time has a distinct rhythm: everything is simply events unfolding between sunrise and sunset. Thus, moments of daily life equally affirm our existence in time, rather than the ephemeral current themes vying to prove their undeniable importance and superiority. It is precisely these themes that the Baltic States’ most prominent contemporary art event intentionally omitted. The entire exhibition is a poetry of the everyday, collected in the form of dysfunctional furniture as artworks and diaries that might serve as guides for recreating the world after it ends. Poetry itself is merely a set of instructions, even if its freedom coquettishly masks uncertain intentions. Even the clarity of photographic reality, which limits the ephemeral freedom of art, was held in check in the photographs by the Japanese artist Yamazawa that I encountered at the end of my tour through the exhibition.

Paradoxically, despite the obvious inflation of words, we continuously keep our tongues wagging, not because we are used to this mechanical work, but because we hope to change our fate through language. Language itself should have won the Nobel Prize for Peace; so many combative misunderstandings have been resolved in a primitively miraculous way through dialogue. In the Triennial’s cinema hall, the term ‘landlord’ sheds its economic meaning, and becomes another linguistic twist, embodying a relic of the past, just like the kilometres of 16mm film rolling throughout the exhibition. A critical gaze, unburdened by analytical theories, is visible not in the narratives aestheticised in film frames, but in the materiality of film itself, affirming that images and sound do not appear out of nowhere. Even the nostalgic hum of the slide projector adds a poetic lightness to the space. In the cinema hall, there is no need to pretend the film’s soundtrack is whispering directly into your ear. The asynchronous hum of projectors is not irritating; instead, it fosters a complete detachment from the nearly unavoidable digital realm of zeros and ones in today’s world. The more I think about this exhibition, the more I sense the curators’ heavy efforts to reveal the mysteries of the past, keeping them steeped in intrigue through every possible mechanical force. Like the works of Villu Jogeva, assembled from generators, transistors, microelectronics modules, and other practical odds and ends; they playfully showcase the creativity of a metalworker and the often-forgotten charm of everyday craftsmanship. Everyday meanings abound in this exhibition, without fireworks, pretension or applause, just the subtle yet continuous hum of the curators’ linguistic engines.

Jean-Marie Straub & Danièle Huillet, “En Rachâchant”, 1982. 35mm film, digital transfer, black and white, sound. Installation view, 15th Baltic Triennial Same Day, Contemporary Art Centre (CAC) Vilnius, 2024. Photo: Kristien Daem

The 15th Baltic Triennial opens with the curators’ representative verbosity: soft sheets of text and rows of letters, cleanly printed in black on white by the exhibition designers Julie Peeters and Valiantsin Duduk. These publication designers, who crafted functional soft-paper spaces, maps and transcriptions, deserve a mention as creators of essential tools for the 15th Baltic Triennial, allowing visitors to turn the pages of ‘The Same Day’ anew. It is no coincidence that the final chapter of the Triennial will also take a printed form. This publication, prepared once again by the curators and designed by Julie Peeters, is expected in mid-2025. The thought persists that this Triennial might have remained a book, despite the aesthetic pleasure brought by wandering through these spaces of paper-white, where artworks appear like punctuation marks. This review, too, could perhaps have been a poem, or merely a quote from an author whom only time can forget. For what are words worth, even important ones, if they are endlessly multiplied?

A quote from Tasos Roussos’ short story ‘The Last Alchemist’

Translated by Rosana Lukauskaitė

15th Baltic Triennial Same Day, installation view. Contemporary Art Centre (CAC) Vilnius, 2024. Photo: Kristien Daem