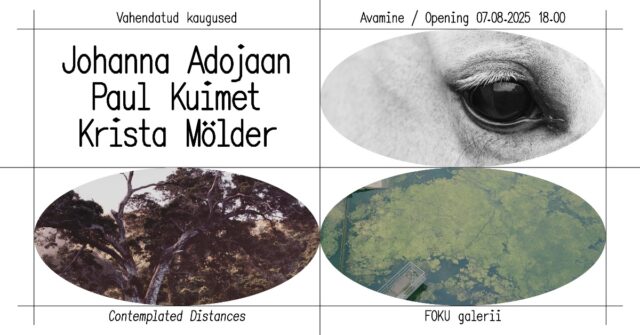

I want a president who is a housewife, a cleaner, a teacher, a nurse, a midwife. Unemployed, a pensioner, childless, a mother of five, a single parent. A woman who loves a woman. A president who wears a skirt, trousers, a sweatsuit …

I want a president who doesn’t have to be guarded, who doesn’t need OMON, but who does need medicines in hospitals, who doesn’t build palaces for herself, or nuclear power stations, who organises no parades, who knows that we are all politics, that war and repression mean the end of politics.

The above words are an excerpt from a manifesto by the Belarussian artist Marina Naprushkina, a work shown at the Survival Kit 13 contemporary art festival in Riga. Written in response to the nationwide protests against Lukashenko’s dictatorship in Belarus in 2020, the work echoes words typed in 1992 by Zoe Leonard, the feminist activist artist who spoke out in support of the queer artist Eileen Myles, who at the time was making a running bid against the whales of American politics George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton. Zoe’s text famously opens with ‘I want a dyke for president,’ from the get-go crafting a path around and beyond straight masculinist politics.

What’s a president? A looming figure of a man, an uncatchable thief, a universalised body of power with no suffering under his fancy leather belt. A figure that is difficult, if not impossible, to imagine away even if brings a threat against us of absolute destruction. The scholars and writers Stefano Harney and Fred Moten thus wondered if Leonard, and all of us who have nothing to lose, could have actually desired a precedent[1] of something else to emerge under conditions of violent oppression.

Installation view of I Want a President by Marina Naprushkina at the Contemporary Art Festival Survival Kit 13 “The Little Bird must be Caught” curated by iLiana Fokianaki, in Riga, September 2022. Photo credit: Ēriks Božis / Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art

Installation view of I Want a President by Marina Naprushkina at the Contemporary Art Festival Survival Kit 13 “The Little Bird must be Caught” curated by iLiana Fokianaki, in Riga, September 2022. Photo credit: Ēriks Božis / Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art

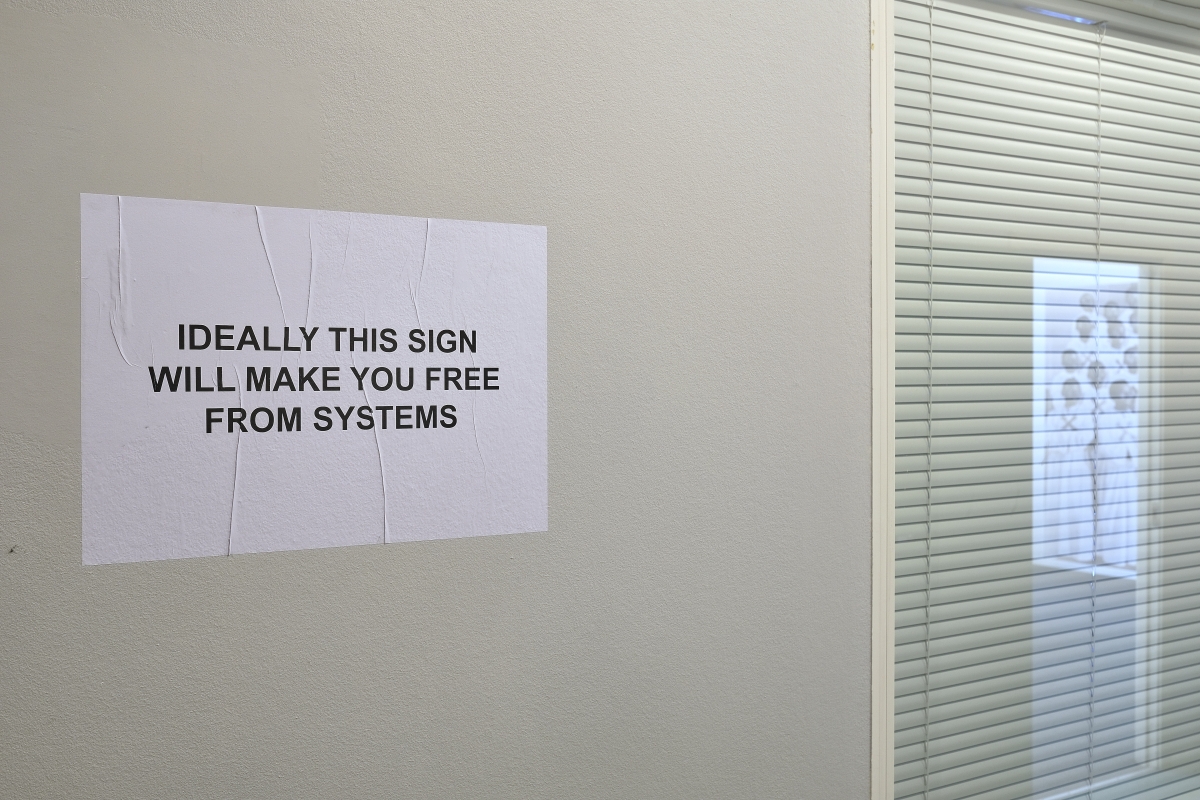

This desire for a precedent is written all over the exhibition ‘The Little Bird Must Be Caught’, curated by iLiana Fokianaki, an iteration of the Survival Kit 13 annual international contemporary art festival that ran from September to October last year. The title ‘The Little Bird Must Be Caught’ references directly a Latvian poem by Ojārs Vācietis, a celebrated poet who in Soviet times mastered cryptic language to speak vividly of oppression. The short work warns of the dangers of a bird’s freedom that gives hope and inspires other birds like it, its song marked by cruelty, coming from within a cage. The exhibition itself is wholly poetic and sonic, being a fluctuating experience full of conspiratorial whispering, through poems, through jazz trombones, through the Singing Revolution: peaceful cultural resistance against the Soviet regime during Perestroika which marched through the Baltics.

Organised by the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, the festival goes on an annual exploration of abandoned facilities. Last year, the location was a majestic and generally daring space previously devoted to guarding money and power: a former bank building in Riga’s Old Town. After a good push on solid wooden doors, an impressive marble interior with high ceilings opens up to the visitor. The cold starts seeping into the bones pretty quickly. But this exhibition requires time: it is large, expansive, difficult to watch at times, there’s no shortage of lengthy films, and sometimes you end up in a dizzying, albeit beautiful, collision of different works.

Crossing the large marble hall and peeking into one of the rooms just off it, I see and hear Wu Tsang’s Girl Talk. Fred Moten, the scholar and poet who was wondering about us needing a precedent rather than a president, spins in garden scenery with a smile, clad in brightly shining crystals and in velvet robes, to Josiah Wise’s swaying gospel-like interpretation of Betty Carter’s jazz classic ‘Girl Talk’ from the 1960s. The video is a work of radiant joy, euphoric ephemerality, and fluidity of body, gender and sonic disciplines, beaming through the hardened clouds of the political climate and finding power in malleable forms of resistance.

They all me-ouw about the ups and downs of all their friends

The who, the how, the why, they dish the dirt, it never ends

The weaker sex, the speaker sex, we mortal males behold

But though we joke, we wouldn’t trade you for a ton of gold

It’s all been planned

Please take my hand

Just understand

The sweetest girl talk, girl talk

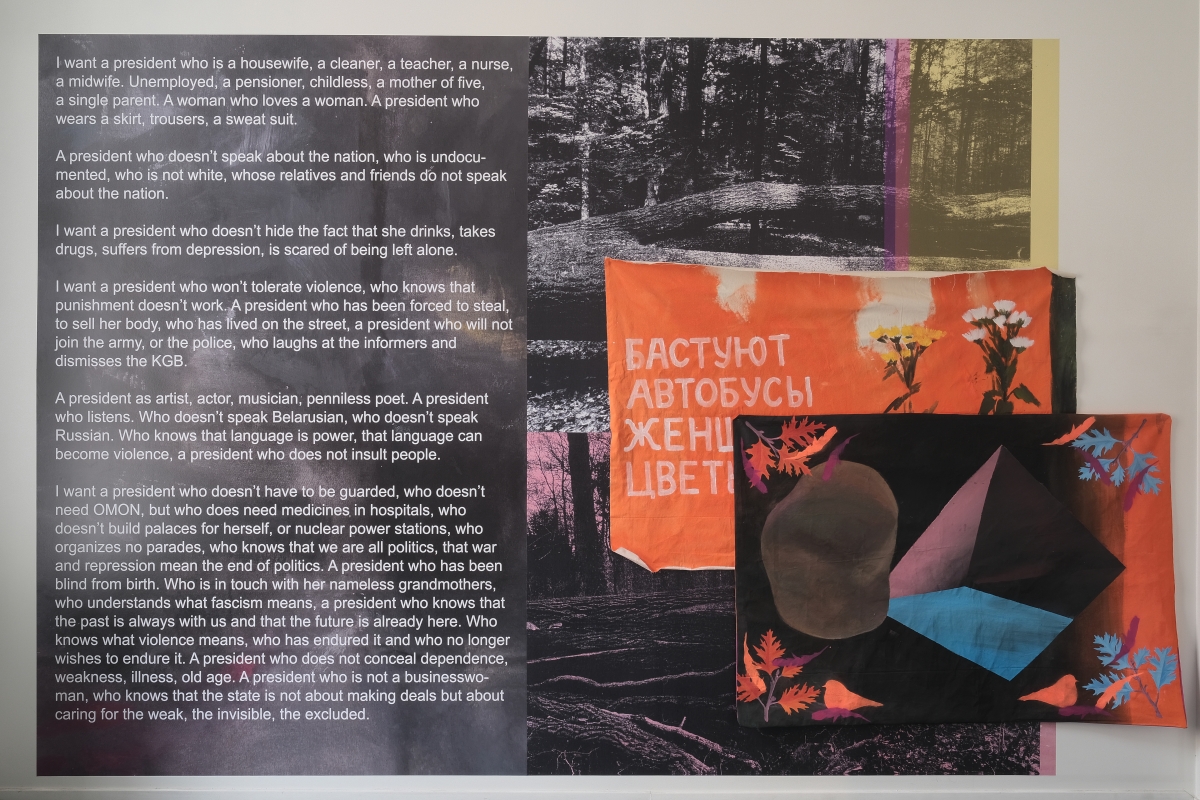

The gospel gently meshes with another swaying melody from a neighbouring room. Kapwani Kiwanga’s work *@!!?*@! is also a rearrangement of a 1960s song, a trombone rendition (by Lauriane Ghils, Nabou Claerhout, Marta Gonzalez and Bianca Sallons) of Nina Simone’s eponymous protest song ‘Mississippi Goddam’. This song appeared in the wake of the killing of four Black girls in the American south in 1963, marking generations of racial violence that saw no end. In the exhibition, the trombone sound fills an empty room, but Simone’s persistent and daring words of great force come to life in one’s head:

Can’t you see it

Can’t you feel it

It’s all in the air

I can’t stand the pressure much longer

Somebody say a prayer

Alabama’s gotten me so upset

Tennessee made me lose my rest

And everybody knows about Mississippi Goddam

From this room with Kiwanga’s work, I am lured by a woman’s whisper coming from yet another nook in the grand bank building.

The voice is a shadow on your face

The sun touching your face

Touches you [lip smack]

Bird flying around stopping on your shoulder

Laure Prouvost’s ‘This Voice Is A Sunshine On Your Face’ is a seductive ode to all unorthodox relations, a memory that slips through the fingers but is felt again and again, a tactile sound entering one’s body. There are three works by Prouvost in the exhibition, placed at different ends: entering the weird-sized rooms of this ex-bank, sounding through the marble halls, and being emitted through a light pink cloud of sorts on the second floor. As I follow the whispers, I keep thinking of them as sonar: scanning and guiding through the exhibition, locating invisible pockets of melancholy, of violence, full of ghosts of the past.

KapwaniKiwanga, *@!!?*@!, Mississippi Goddam from the Album

Laure Prouvost. Installation view at the Contemporary Art Festival Survival Kit 13 “The Little Bird must be Caught” curated by iLiana Fokianaki, in Riga, September 2022.Photo credit: Ēriks Božis / Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art

Laure Prouvost. Installation view at the Contemporary Art Festival Survival Kit 13 “The Little Bird must be Caught” curated by iLiana Fokianaki, in Riga, September 2022.Photo credit: Ēriks Božis / Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art

War is not a singular act; it is not even a time-bracketed armed event between two opposing sides. It is a singularity folding on to itself and taking us with it along new migratory routes. I am thinking of this after having encountered the curator Fokianaki’s question, how we address art and survival in the middle of war and destruction, which she immediately flips back on to itself, of the possibility of art in the middle of war and destruction. These questions are a huge undertaking that has been especially painful since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine this year, becoming a horrible, long drawn-out war. Few of us were left without the urge to rethink different facets of life, including art and culture, in the face of the unimaginable brutality and violence.

The curator addresses war and destruction, dark waves of economic, health and cultural crises, through very specific agents of ‘narcissistic authoritarian statism’: Orban, Putin, Trump, Erdogan and others, all these representatives and instigators of an insidious slide of the world into rightwing authoritarian politics and dictatorships. It is worth staying a bit longer with this term coined by Fokianaki, reintroduced in the conceptualisation of this exhibition. ‘Narcissistic authoritarian statism’, put very shortly, is neoliberal state governance dependent not only on corporate logistics but also on the grasp of a singular political leader, which itself produces narcissistic individuated subjects, who are capable of caring only for themselves and not for Others.[2] While this understanding and analysis of neoliberal state governance, which erodes the separation between corporate and nation-state logistics, and also between the Self and the institution, is not something unheard-of, Fokianaki hones in on narcissistic political leadership as a pressure point for art to address.

So is art our sturdy boat that holds up in the whirlpools of narcissistic state violence, or maybe a tool for conquering them? An embrace of differential imaginaries outside the extrastatecraft? Or maybe, as Fokianaki has suggested,[3] art can also be guilty of the internalised perpetuation of narcissistic governance, as seen in cultural institutions, the art market, and artists-powerhouses? Of course, art can be all of this, and none of this; but in this perpetual motion of war and the disintegration of togetherness we keep finding ourselves in, these questions need at least to be asked, if not answered.

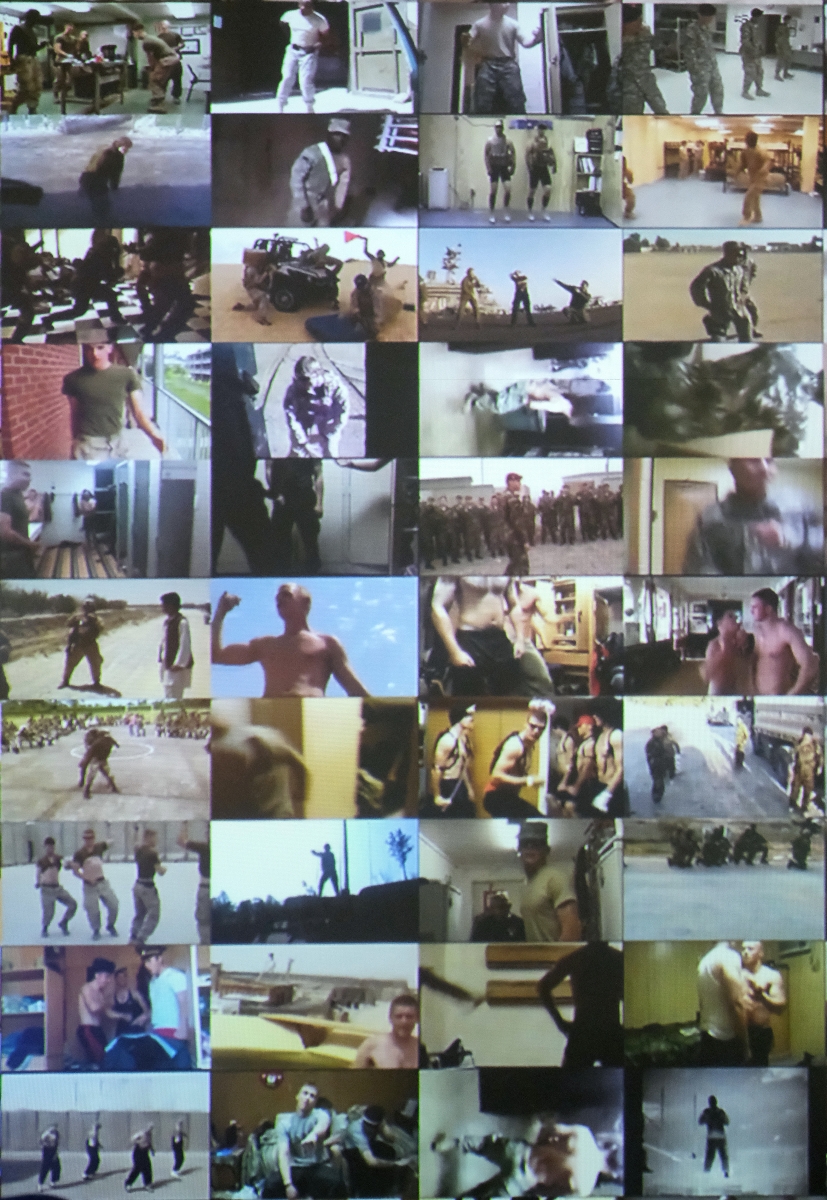

Installation view of This is How We Win Wars by Indre Šerpytyte at the Contemporary Art Festival Survival Kit 13 “The Little Bird must be Caught” curated by iLiana Fokianaki, in Riga, September 2022. Photo credit: Ēriks Božis / Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art

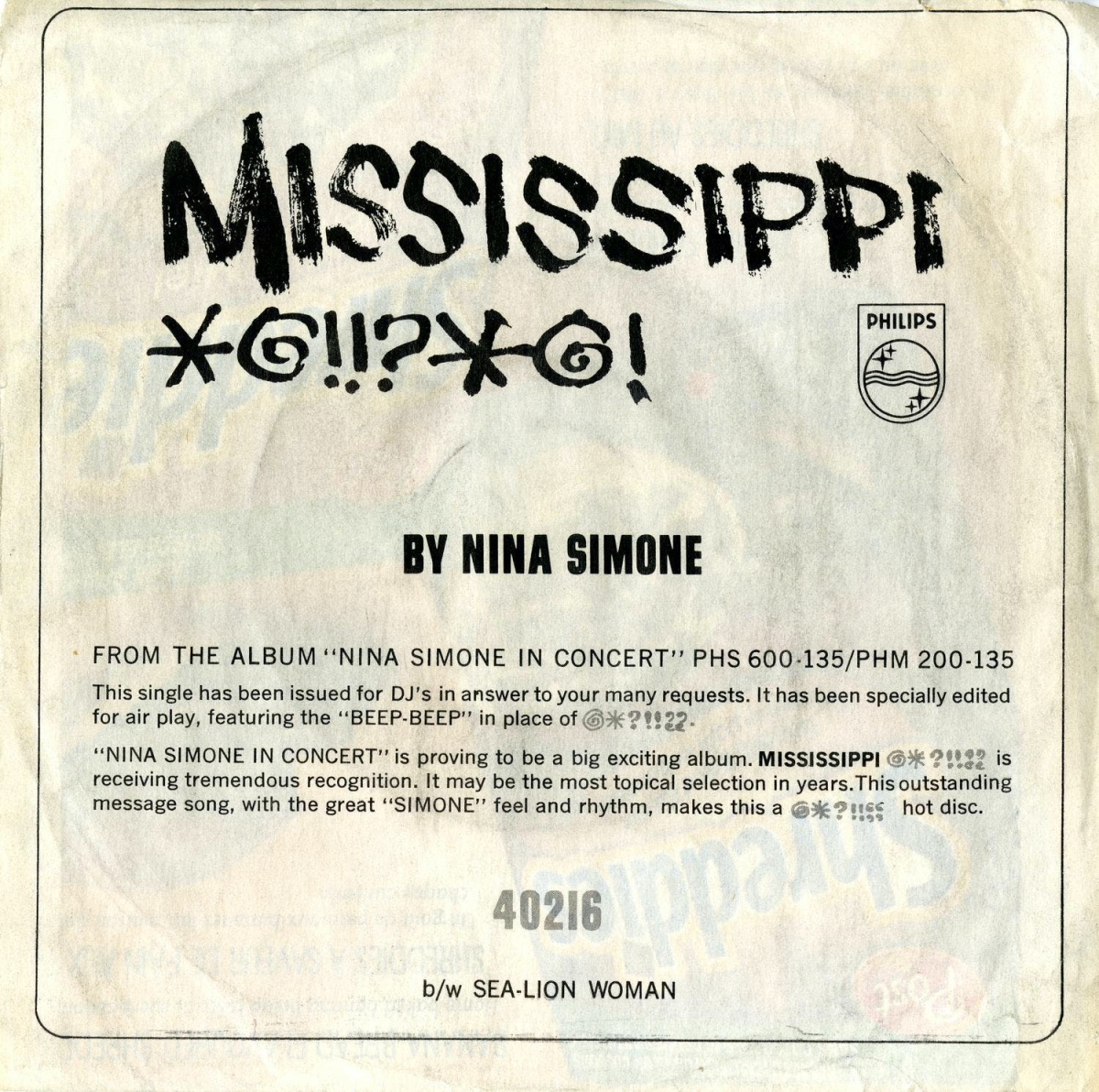

On the second floor where one of the (pink) whispers by Laure Prouvost resides, there is a harsh shift in the scenery. Leaving the marble halls behind, a labyrinthine floor full of various-sized office spaces appears, each holding an artwork, and usually a video work. It is much more a game of hide and seek here, with the growing unease of being watched, surveyed and algorithmically witnessed by the authoritarian eye of technology. An array of works addresses a complicated suspension between witnessing and being witnessed, within the technological realm and beyond it.

Indrė Šerpytytė’s work This is How We Win Wars is a wall of YouTube video squares, each showing soldiers dancing. Their occupation is clearly evident: soldiers wearing dark green military clothing, but some almost naked, moving in tight barracks spaces full of bunk beds or in the open air, a constricted area for training. The soldiers move according to makeshift choreography, emulating popular dances or making uncontrolled motions to music we can’t hear. Rather, it is accompanied by a sound piece by Steve Reich, built in sequences, starting out quite sparsely, and at the end entering an energetic pulse affecting the body. Bearing in mind the context of the war in Ukraine happening so close, seeing these soldiers of no clear (at least for me) national assignation, in relaxed, even silly, moods and stances, arouses feelings of aversion; remembering that they are soldiers on both sides of the war does not alleviate the uneasiness. The videos in Šerpytytė’s work come from a techno-corporate platform, some of which were uploaded by the soldiers themselves, providing an entry into enclosed disciplinary spaces with no civilian access, as well as giving their bodies up to algorithmic control.

Another work that revolves closely around war, as a single but also a singular event, is by Forensic Architecture, who, in their modus operandi, investigated down to the smallest detail a violent event, the bombing of the Television Tower in Kyiv in 2022. The work Russian Strike on the Kyiv TV Tower recounts an attack not only on a means of communication in an occupied country, but also an attack that revived violent history: the missiles missed the tower and landed in the Babyn Yar site of Holocaust massacres. With surgical precision of computational means, Forensic Architecture investigate every trajectory of the event, by reconstructing the missile routes and historical facts, civilian and media footage, and piecing together a ‘full’ narrative from neat archival compartments. Such an airtight space of evidence might be said not to leave any room for doubt about what actually happened, creating a space where we can witness the technology back to itself, and possibly the violence to itself as well.

If ghosts could talk back, it would look like Candice Breitz’s Whiteface. The South African artist poses a double-edged video that makes one’s head turn, literally. The larger screen features comically and threateningly white figures personified by the artist herself: obvious wigs of blonde hair, spooky bright blue eyes, and crisp white shirts that would do well in a corporate job interview. As I enter the room, I hear the words ‘All my life I have been white, and I am proud of it,’ spoken by one of the figures. However, there is a smaller screen in front of the larger one, where it can be seen that the figures are merely mouthing what actual people have said in their videos on their social media accounts, and what reactionary news anchors such as Tucker Carlson of Fox News have narrated. It is material collected as part of an archive entitled ‘white people talking about race’ that Breitz collected over the years (not unlike how I imagine Šerpytytė’s mode of sourcing had to go, looking for dancing soldiers on YouTube) about exploring racial tension, herself being a white artist from South Africa. Such screen doubling delivers the doubling of appropriation: appropriating what has already been appropriated and taken away from many of us, witnessing algorithmic violence to its very end, and enlarging it in bold performative acts.

‘The Little Bird Must Be Caught’ is an exhibition with many questions, embracing them in a cascade of visually, sonically and vocally very strong works, each proposing a different mode of resistance to racially, ecologically and extractively oppressive governances. ‘Dizzying’ might be the word here: the exhibition is heavily, although not heavy-handedly, loaded with different worlds and histories that cannot be made out clearly in one visit, and not in one text about it (and this text itself has taken a fragmented form and a differential rhythm of its own). Like any large exhibition, and this is a festival seemingly growing in scale each year towards the size of a biennial, it will sit in the visitor’s mind not as a detailed map, but as a cluster of intensities woven from the works most attractive to one’s subjective eye and ear.

A precedent arises when we don’t have the option any more of not having an option, as Harney and Moten say. Such a kaleidoscopic exhibition, combining many and very different historical and personal worlds, might rekindle that desire for a precedent of a world built otherwise, which would overcome the need for yet another agent of narcissistic authoritarian statism, yet another representative of ruthless oppression of the communal will. These works come together in the shared understanding that politics-as-usual does not work. Can art provide a vital hand in all of this?

Wu Tsang, Girl Talk, video still, 2015. Copyright and courtesy the artist

Installation view. Ansis Epners, Contemporary Art Festival Survival Kit 13 “The Little Bird must be Caught” curated by iLiana Fokianaki, in Riga, September 2022. Photo credit: Ēriks Božis / Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art

Installation view. Ansis Epners, Contemporary Art Festival Survival Kit 13 “The Little Bird must be Caught” curated by iLiana Fokianaki, in Riga, September 2022. Photo credit: Ēriks Božis / Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art

[1] Stefano Harney, Fred Moten, All Incomplete. Minor Compositions, 2021.

[2] https://www.e-flux.com/journal/103/292692/narcissistic-authoritarian-statism-part-1-the-eso-and-exo-axis-of-contemporary-forms-of-power/

[3] https://www.e-flux.com/journal/103/292692/narcissistic-authoritarian-statism-part-1-the-eso-and-exo-axis-of-contemporary-forms-of-power/