The text has been edited down for clarity and style. Any misunderstandings are my own.

DOVYDAS, generalises, speaks faster than they think

NERINGA, cushions statements with ‘kind of’, ‘I guess that’, ‘somehow

An almost empty chain café in the heart of the city centre. Near the entrance, a table with a leather-padded, tan bench on one side and a black, plastic chair on the other. The table is slightly hidden in the shadow created by the coat rack next to the light of the glass door. Unoffensive music plays at a comfortable volume from the speakers. In the distance, a barista is banging a portafilter to get the used-up coffee grounds out.

At the table, on the bench, sits NERINGA, dressed in a breathable, canary yellow dress, on her phone, with a cup of freshly brewed coffee and a canelé on a plate in front of her. DOVYDAS enters through the glass door and instantly sees her. After a moment of stillness, they move into her line of sight, catching her attention. She smiles and stands up to shake their hand.

Sitting down across from each other, they politely exchange beginning-of-interview pleasantries. Meanwhile, DOVYDAS reaches into a black tote bag and takes out a notebook and a microphone inside a small, plastic pouch. They connect the microphone to their phone and give it to NERINGA, who pins it to the neckline of her dress.

DOVYDAS. Let me make sure it’s recording. I always have such a fear that once the interview is over, I’ll see that I forgot to press record. Okay, looks good…

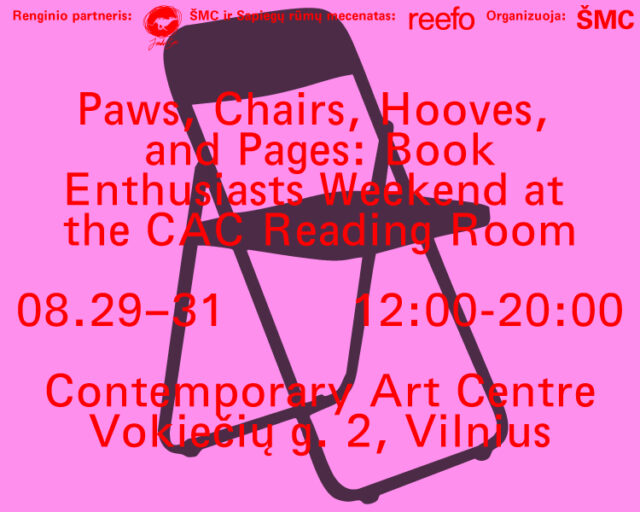

So! I’m very excited about the first Vilnius Biennial of Performance Art which will take place… (checking notes) between the twenty-third of July and the sixth of August across the city. Just to start with, I want to know a bit about your relationship with performance art. What has been your journey with it? Was there a particular moment when you fell in love with it? Just whatever comes to mind.

NERINGA. It all started when I was invited to join the team as the artistic director and actually, at first, I didn’t agree because I was so busy working on the Lithuanian Pavilion in Venice, but they were really persistent and, in the end, I felt it could also be a new chapter for me.

Beforehand, I was mostly working as an exhibition curator. Of course, I had a few collaborations with performance artists; specifically with one curator, Vincent Honoré, with whom I worked on the thirteenth Baltic Triennial in twenty-eighteen. Back then, he was still the director of the David Roberts Art Foundation in London and was interested specifically in performance art.

I don’t know if nowadays you can separate performance art from the rest of art and it was interesting for me to invite people who are not mainly working with performance art; there are quite a few names in our programme who are primarily known for other media. So the biennial is a new platform for experimenting with artists to see what this new, at least for me, field can open in terms of possibilities and discoveries. Even though I’m working with performance, I feel that it’s much more than only that.

DOVYDAS. I’m going to give you a bit of a throwback to your master thesis, written on ‘animism and objecthood in neo-conceptual art’, which to me, speaks very much about the performativity of objects in questioning whether an object can become a subject, and therefore become live. It seems to me that even ten years ago, there was a growing interest in performativity and performance. Is that something you recognise consciously as having developed from that area of interest?

NERINGA. (smiling) I’m very surprised that you dug so deeply.

Let me think… I guess it is connected to my roots as a person, looking at the world as something intrinsically alive and not something that we have the power to completely direct. Of course, the thesis in twenty-thirteen was influenced by the then-new philosophical ideas on object-oriented ontology.

I would say I look at everything as—I don’t want to use this word—but as a miracle. Everything has its own power to act and change the surroundings and everyone within it. This does not only apply to my professional activity but also to my personal connection to the world and the way I see and engage with things. I see agency everywhere… so it probably makes sense that now I work with performance art.

DOVYDAS. Of course, object-oriented ontology is now very trendy and it was fascinating looking at your thesis because it felt like you were building towards it before that term had fully emerged in the popular imagination. So it seems like you were ahead of the curve.

NERINGA. (laughing) I don’t want to take too much credit…

DOVYDAS. You created object-oriented ontology!

NERINGA. I guess there were some ideas in the air already… and I kind of felt back then, and I do feel now…

(Adjusting her posture) So, I was raised with this mix of some kind of old, ancient Pagan worldview, which was intertwined with Christianity, which was then intertwined with neoliberalism coming to Lithuania after we regained our independence in the nineties, so this kind of ontology was not foreign to me. I felt that there was something in me already speaking to it.

DOVYDAS. It’s fascinating the way our Pagan roots create an intrinsic understanding of performativity, like with the fork falling off the table signifying the arrival of someone. Yet, I must say that as a performance artist, I always feel like performance is under-represented in the Lithuanian art landscape among other mediums, and the work I do see, I would think of as closer to performing arts, rather than performance art as there is often a fourth wall that separates the performers and audience.

Coming from the London live art scene, I have my own subjectivities, so I do have to check myself a bit. But with the first edition of the biennial, there is a positioning happening that in a way defines what performance art is in Lithuania, so is that something that you’re thinking about as a responsibility, specifically in this idea of the Lithuanian canon and finding that identity among the distinctions and aesthetics of other countries?

NERINGA. All of us as Lithuanians went through many raptures in our lives. I studied curating in France and had a rather close French friend with whom we had many discussions through which I found out that there are so many things that are different for her and me. She experienced a certain continuity and stability in the history of her country, while I saw one system collapsing and bringing everything down with it. Of course, we were super happy about it, but still, there was a huge change and then new things came and you had to deal with it. No one was taking care of you whatsoever.

Professionally speaking as well, I was dreaming and thinking that I will be a designer and then one thing followed another, and I became an artist and then I became a curator working in visual art, now working with performance art; I lived here and there and there. So I guess don’t really know what the Lithuanian art scene is. I don’t think there is as much of a Lithuanian art scene as there is a Vilnius art scene, Kaunas art scene, Klaipeda art scene, Nida art scene.

Pause

When I graduated from my studies in France and was then directly invited to join the team at the Contemporary Art Centre in Vilnius, I didn’t feel, how to say, one of them. It’s a good question; what is the Vilnius art scene? I’ve somehow never felt an intrinsic part of it and it’s funny because when I hear myself saying this, I think ‘Yes, I did the Lithuanian Pavilion, the performance art biennial, many projects at the CAC’, but I felt I had my own vision and certain kinds of responsibilities that needed to be done and addressed which didn’t exactly coincide with the Vilnius art scene.

DOVYDAS. Your sensibilities didn’t quite match up with what was happening in the art scene?

NERINGA. (shrugs) Maybe it’s me. I don’t know. I always do feel a bit like an outsider, and it comes with a certain struggle because you constantly have to prove yourself and find your place within a certain structure; but it also comes with a certain freedom, because I don’t owe anything to anyone so I can be rather dynamic and do things I feel need to be done.

I don’t know if it’s proper to speak of it this way but I felt that the Vilnius art scene was very much influenced by conceptual art from the beginning of the two-thousands and a certain materiality and heaviness was lacking in the art field.

I’m speaking for myself. I have worked so much with conceptual art and I love conceptual art, but I think the world is a lot more complex than that and we are not only ideas, we are also bodies. Our bodies sometimes feel good, sometimes are sick and getting old; we are in this space and everything in the room affects me: the sound that plays, perhaps you have a smell, perhaps I have a smell, the smell of coffee, someone is passing by… I felt this kind of reality was a bit missing in the Vilnius art scene and I wanted to work with that.

So perhaps what interests me the most is having art that addresses the most urgent things happening in my life, not only as a professional but also as a human being. I don’t intend to oversimplify things or be direct, but I was missing the things that were speaking to what is important to me today.

DOVYDAS. So your answer to my question of setting the tone for performance art in Lithuania is that you’re not thinking of it that way and just using your curatorial practice as a way of processing your experience as a being in this world, rather than kind of taking on this role of ‘I am the curator and I will decide…’—

NERINGA. (shakes her arms in protest and laughs) No, I hate that, please no, no, no, no.

DOVYDAS. Speaking honestly, I looked at the programme and saw that there were quite a few artists who don’t usually work with performance, which I found a bit frustrating—

NERINGA. Why?

DOVYDAS. Well, to be transparent, I did apply…

NERINGA. You applied? I’m sorry—

DOVYDAS. (laughing) It’s totally fine! Looking back, the project was so underdeveloped. But I also have performance artist friends in Lithuania who are incredible, and it seemed that the programme was more giving space for artists to experiment with performance art rather than necessarily highlighting the existing performance art scene. On the other hand, I feel like within art in general, there is a move towards transdisciplinarity. You can see it in music with the dissolution of genres or the meta-meshing of styles in film. Maybe this is just the flow of things, and we are also moving towards a kind of fundamental transdisciplinarity within contemporary art where people are not necessarily thinking in those very strict categorical terms. Is this how you see it?

NERINGA. Yeah, so thank you so much for your remark. I hadn’t thought about it from this perspective, but I totally see what you mean. While you were explaining your position, I was thinking… sometimes you make decisions without thinking too much but something in you tells you to do it. I can understand that certain performance artists who work deeply in performance art might be a bit disappointed not being invited to the programme.

I was invited to do this festival and I arrived with all the background I have, with all my sincerity and openness. But I guess my intention was also to, as you noted in your remark, open contemporary art and make it more accessible to wider audiences. I felt it was specifically needed at this time because we are going to the city and it is also a festival of the city. It’s not somehow enclosed in one institution, which is dedicated to theatre or whatever, it’s throughout the city and unites different institutions and non-institutions.

DOVYDAS. When I came back to Kaunas in two-thousand-and-nineteen, I heard people say they hated performance art and didn’t want to see some person cutting themselves on stage. Performance art has strong connotations of being visceral, painful or really difficult to stomach, which is only one kind of performance art, but it becomes a stereotype that people tend to have. So what would you say to those who have these kinds of preconceived notions or stigmas around performance art to get them to come to the biennial and have this opportunity to maybe change their minds?

NERINGA. Funnily enough, when reaching out to the representatives of the locations we wanted to work with, sometimes one of the first questions was if we would show nudity and if there would be violence. I must say, I’m very far away from these things and I think that performance art historically went through different stages and there were experiments in the body and endurance of pain already happening in the seventies and eighties. I think the questions that were important to answer have already been answered. The field now is a lot more sophisticated, not only philosophically but in the subtlety of the way it addresses different questions that are important in our society.

Pause

I feel that the focus is somewhere else. I think the joy and the fulfilment nowadays is that there are so many different things happening in the world and it’s difficult to say that performance is this or that. Go to any bigger exhibition or biennial and you will see so many different practices happening at the same time. It’s a question of where you stand and what you’re looking for. Of course, here I’m subjective. I’m looking from my perspective.

DOVYDAS. There is this quote from your interview with IKT Spotlight where you said, ‘Among my areas of interest is contemporary art that sensitively reflects the challenges of the current world and helps imagine the future’. That’s kind of what you’re saying here: that you feel like there are very different questions to answer. So what are some of those questions?

NERINGA. In terms of the biennial, one of the main challenges for me was to create a framework of what I’m looking for and what the artworks will be addressing. It made total sense to focus on the city for the first biennial because it coincides with and is primarily financed by the anniversary of Vilnius’ seven-hundredth birthday. It’s such an important and sensitive moment to think about the city as a human-made structure that has its own rhythm and is somehow alive. We’re seeing so close to us all these structures being brutally destroyed.

The city is our focus with all the different tensions, desires and visions overlapping, coexisting and confronting. (looking at the cars passing by the window) In the beginning, I was thinking of the city as visible and invisible structures, things that are addressed openly, together with more shady and vague fields like politics and different power interests.

What was also important for me was the female voice or voices who have been suppressed since a long time ago and now is the moment to let them speak. So I really wanted to open the biennial with a female artist. With Emilija Škarnulytė, we had many discussions and she was constantly saying that she still felt somehow overshadowed by bigger, male artists. So I wanted to give her the Opera House, which is normally a huge, masculine structure. Give it to a woman, let her experiment with it and do what she needs to do.

Pause

After Venice, I was invited to different kinds of presentations of my practice. Only then I realised that the majority of the artists I was working with beforehand were male. Very inspiring people that I work with until today. But I didn’t make these decisions consciously. I asked myself: how did it happen? How am I functioning? How does the world function so I only want to make certain voices heard? In the frame of the biennial, I was very conscious of this. Thinking ‘Who are these people?’.

DOVYDAS. I definitely agree with you and I think it is the same discussion that’s being had within film. There is a lot of work made by one type of person and there’s an extent to which you can push that perspective. When you give the space for voices which are not typically given those main creative roles, there’s just something fundamentally different about their way of looking at the world. It’s exciting to have that shift of perspective.

NERINGA. Exactly, exactly. Very intentionally, I wanted Adam Christensen to be performing in the city. I didn’t want him to be one in one of those closed-off spaces, I wanted it to be accessible so that people passing by could see. We still haven’t managed to address the rights of the LGBTQ-plus community, I think it’s a shame for our country and we need to do it as fast as possible. So I want him to be visible and Adam is amazing, he’s such a talented person. It’s always such a pleasure to see him perform.

In the programme, I do have some sophisticated, male, strong artist figures, who are also very enriching in their own way. So it’s not to say: ‘We’re not showing you anymore, forget it!’. (laughs as she trails off)

DOVYDAS. Now you have fifty years of oppression!

NERINGA. (still laughing, under her breath) Fifty years…

Everything is here and it’s super beautiful. All these various perspectives can give us different ways to solve our biggest challenges and raise important questions in this field.

Going back to your question, there are different sets of questions. Now I’m thinking about Liam Gillick and Anton Vidokle who in their work question: what is your responsibility as an artist or as a practitioner in the art field facing these huge geopolitical crises? What can you do and what can’t you do, and what is important to be done? It’s a big question. What agency does art have? I’m sure it has lots of agency, but it has its own limits as well.

DOVYDAS. Before, I asked you about your quote from the interview regarding contemporary art that reflects the challenges of the world and helps imagine the future. We answered the first part, but what about the futures you would like the biennial to imagine?

NERINGA. I guess I’ve already somehow touched on this. I’m interested in practices that are trying to understand how we can make things more sustainable—

DOVYDAS. Sustainable for the world, or the artist—

NERINGA. For everyone. For the artists, for human beings, for other beings on this planet. Every morning I’m reading this briefing from the New York Times, and for the last few weeks, one of the first articles is either about the war in Ukraine or the heat wave in Southern Europe and the United States. As a society, I think we are approaching the moment… we approached the moment when we need to change something to basically survive.

It’s also about being rather simple, being on the ground. Like the work by Eglė Budvytytė and Marija Olšauskaitė—you could read it as a call to slow down the pace of your life and be more present with yourself and the place you’re in with the living and non-living things that are around you, seeing how you can move from here to a future that is more in tune with you.

DOVYDAS. Imagination is a very critical juncture because to reach a future, you have to be able to imagine it. If we also think about artists as steering the imagination of the communities they’re in, it’s as if we are all on this boat and artists are the ones rowing. Maybe that’s too grand of a statement about the role of an artist but I think it’s something all artists think about: What can I actually do? What is my sphere of influence?

NERINGA. Exactly and it’s important to understand that we have an influence. We are not saving lives at the frontlines of war; we are neither soldiers nor doctors. But we are making a real change and it’s important to understand our power. This moment of imagination is crucial. I was giving an interview a few years ago and someone asked me ‘What are you searching for in art, not just as a curator but as a person?’. I said, ‘I’m searching for ways to survive’. Not in the sense that I need food or water, but as a human being wondering how to survive this life with all these challenges. Art for me is the place where I go to search for answers, for consolation.

DOVYDAS. Continuing in the vein of imagination, something that helps us imagine the future is sci-fi and in the same interview with IKT, you spoke about the fact that you’re an admirer of sci-fi…

NERINGA starts laughing

DOVYDAS. —Which I am too! So I wanted to ask: if you could recommend a companion media piece for the biennial from this genre, what would it be and why?

NERINGA. A few days ago, I started remembering and thinking about the Dragonfly chapter in Tales from Earthsea by Ursula K Le Guin. (slowly recalling) It’s about a girl who is not allowed to learn magic. There’s this huge, very important school for magic and it’s completely closed off to women. Then, this young woman comes along from a difficult background, she is also difficult, she doesn’t obey rules or behave how she’s expected to…

To make a long story short, she manages to sneak in pretending to be a boy, even though everyone knows it’s impossible to trick the magicians guarding the entrance, then, they have a huge discussion about whether she should be let in because they sense that she has very strong powers, but then they decide against it, somehow, I can’t remember in detail, but one thing follows another… and the most powerful creatures in this world are dragons who can speak this language of magicians, that magicians only learn at school… and there is some kind of fight and then this girl suddenly turns into a huge dragon.

Turns out she was this beautiful, powerful dragon just in the shape of this little girl.

So… I hope that this festival can help us discover the powers we have within us.

DOVYDAS. (nodding) Nice answer…

NERINGA starts laughing

DOVYDAS. I think I’m coming to the last question, which I don’t think will be too difficult to answer, it’s short. I wanted to ask you to give us an intriguing but vague statement about what we can expect from the biennial.

NERINGA. Intriguing but vague? Oh my god. (Exhaling loudly) I don’t know how to make it intriguing—

DOVYDAS. But vague!

Pause

NERINGA. To relate to the answer I gave you previously, I would say there is lots of magic in all the performances.

DOVYDAS. (nodding again) Great, intriguing but vague! You were successful.

NERINGA. I hope that you will be able to find the magic.

DOVYDAS. I’m sure I will, I’m coming to every performance—

NERINGA. (laughing) Amazing, me too! (crosses fingers) I hope everything goes well.

DOVYDAS. I’m sure there will be surprises but for me, those moments are always the most enriching. I feel that as a performance artist, I seek that which I cannot predict. Then it feels like something is happening in the here and now, between the connection of the audience and the performer. Like when I did that performance on the trolleybuses, one of the most memorable moments was when I got thrown out of the bus by the driver with all the passengers yelling ‘We don’t want you here, get out!’.

NERINGA. Really?

DOVYDAS. Yes, yes. I really love that moment because they gave me so much of themselves, their time and energy when they could’ve just ignored me, and now it’s one of the highlights from that performance.

NERINGA. It’s a very interesting approach. It’s also encouraging to hear that. Seeing all the situations as things that may profit you, inspire you… hopefully not break you (laughing)

You know, last year I was invited to write this…

Actually, I don’t know if I want it to be recorded…

DOVYDAS. I’ll stop the recording… just a sec, my phone screen is recovering from a horse bite

NERINGA. (taking off the microphone) Oh my god…

DOVYDAS. My sister rides horses and one day at the stables a horse bit the screen, so she got herself a new phone and gave me this one. (after some intense pressing on the screen) Okay, saved.

NERINGA hands DOVYDAS the microphone and they shove it unceremoniously into the same, plastic pouch.

DOVYDAS. So you were saying…

They continue talking as the music swells, drowning out their voices, and the lights dim into darkness.