Can we sense and talk about others? How much of them is within us? How are projects influenced by different collaborations, both with so-called human and with non-human others? How far can we trust our own senses?

This conversation is a continuation of the talk ‘Experiencing Lives’ at the Ars Electronica festival, and of its subsequent creative workshops. In her event ‘The Plant Oracle’, Brigita Kasperaitė invited participants to sense a plant through an electric current circulating between it and a person. Kamilė Krasauskaitė led her workshop ‘Sourdough DNA’ with the aim of prompting a dialogue between material, its surrounding environment, its geographical position, and its proprietor. In her workshop ‘Rethinking Alive as Material’, Rūta Spelskytė invited us to consider possible events that would follow encounters between cochineal bugs, fluorescent seaweed, kombucha, seeds of the dancing plant (Codariocalyx motorius), and green stain fungus (Chlorociboria aeruginascens). Mindaugas Gapševičius invited everyone to make and experience personalised yoghurt. This conversation with the artists in all these workshops was initiated by Valentinas Klimašauskas.

Valentinas Klimašauskas: During this dramatic, yet still festive, period, we often begin to consider the symbolic turn from the past to the future, from one year to the next, and our state in this constantly shifting world, in which even notions such as ‘I’, ‘the other’, ‘time’ and ‘instruments’, and the language we use, keep changing. These terms sound very different in the current pandemic. Can you tell us about the limits of the possible relations we might have with various others (whether it be microorganisms, plants, etc.). To what extent are such relations imaginary? Are they bilateral, and if so, how can you determine it?

Brigita Kasperaitė: In my opinion, such bilateral relations exist only for as long as we keep imagining them. Unfortunately, we cannot translate what those ‘others’ think of a human, that’d be an attempt to predict another species’ intentions and emotions, which today is still simply impossible. Hence, in this case, the limits are drawn from the human perspective: we start off from our own intentions.

Mindaugas Gapševičius: I agree with Brigita. And I’d like to answer your questions by starting with the last one, about mutuality between the other and myself. As I was growing my bacteria colonies, I noticed that they tend to adjust to each other, to share their territory according to the speed of growth. Perhaps the question becomes more complicated when you consider two organisms that function on entirely different levels: for instance, humans and the microorganisms living on their skin. You might think, say, about sweat, how it intensifies the multiplication of certain organisms. Mutuality is inevitable. However, on the other hand, bearing in mind the fact that different organisms have different sensory systems, we can only continue to speak within the confines of the imagination.

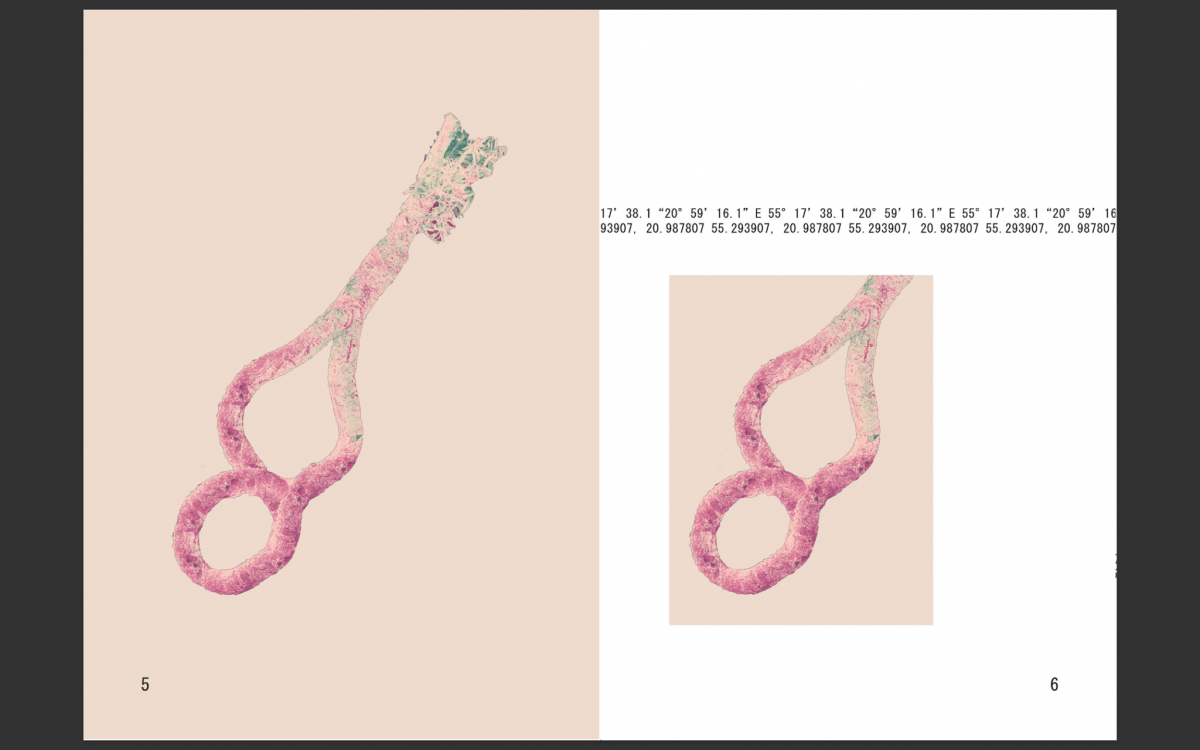

Still from Kamilė Krasauskaitė’s video work

Kamilė Krasauskaitė: Once it enters the dough starter, most wild yeast or lactobacillus bacteria keeps on multiplying; therefore, the substance and its map become richer. That’s an interesting problem in the context of globalisation: perhaps the bacteria could be imported as well. Just as in Mindaugas’ project, where the gut microbiome possibly affects our well-being, our emotions and our perception of the world, through the cycles of dough starter fermentation we metaphorically train and get used to installing new experiences and realisations. We become more flexible, and more resistant to unexpected changes.

During our virtual meetings, we also discussed the boundaries between ourselves and the other. Here, skin and other surfaces were permeable membranes (not any sort of distinctive features), i.e. the surface for the metathesis between substance and transformation itself. Even the bread, the end product, was in a way translated, since the environment became our research field, while the wild yeast and the bacteria became the environment for flour and water.

Rūta Spelskytė: We could also consider the story of how Berlin blue (Prussian blue) was made from Cochineal red; or to be more precise, one version, according to which a mixture of potash, iron sulfate and Cochineal went blue from a single drop of blood when the person mixing them accidentally cut his finger. The boundary between I and the Other seems to be more the ratio between the ingredients of the compound I-and-Other, and not some separate parts. It is much more interesting to think of their intra-activity than to try and look outwards.

VK: Although, when we talk about the other, we usually talk about the external other, how important to you is the relation with the unknown variables within us?

KK: That unknown variable can divide into new variables; eventually, an actual constellation of them may appear. That’s why I’d call my own relation, as well as that of the workshop participants, processual or performative. However, in this case, the performativity lies not within some acts, not within the pandemic’s virtual meetings; instead, it is delegated to organic materials and microorganisms. The bread starter, in its intrinsic sense, would simply be meaningless if it didn’t have any contact with factors such as oxygen and bacteria, which create new meanings and new quality. Another goal, in my opinion, is the relation between the specific substance and its supervisor: participants should see themselves as acting together with the starter, and as creating new significations. Unmindfully, most participants chose to investigate substance through language (poems), meditative journeys, or their own rituals, created personally or otherwise found in texts. That could even give grounds for the connotation in Valentinas’ question linking us with the subconscious and the phenomenon of embodiment, the embodied mind and the dualism of the body, the interpretation of many worlds. The workshop participant is a mere intermediary, who reveals semiotic significations without twisting them, and makes them perceivable to the senses in an accepted format.

RS: I instantly imagined the Cordyceps and Leucochloridium paradoxum :)…

If the other is different, or does not act according to our will, it is treated as a parasite or a threat, we turn to pills or exorcism. But perhaps that’s where the whole complex allure actually lies: one ought to admit there is no need to control everything. I like to think of the power humanity has over the Earth, how it is slipping away from our grip; and yet we could look at our relation with ourselves in exactly the same way.

Ainė Petkūnaitė ROSEASIS RADIXUS HARENAEBE

VK: Does the relation with the other have any influence on how we use and make sense of language? Can language itself be understood as that other? For example, William Burroughs once called language ‘a virus from outer space’.

MG: I think we’ve taken an interesting turn. I’m beginning to think how we observe our friends, colleagues and other people, and seamlessly take on their attributes. By trying to sense these others, that is, by borrowing their manners or qualities, we can begin to understand our language in a different way. Moreover, since a changed language has influence over us, we could start thinking about the interactivity between us and our language.

RS: Indeed, as we attempt to comprehend each other, we adopt others’ attributes: certain words spread within a circle of friends, or they begin to act as codes in certain closed-up bubbles; then they wither or spread even further. It’s fascinating to think of it on that level as a virus; why are the main instruments of communication words in particular? Maybe the communication between trees and fungi is still incomprehensible to humans.

VK: How have your projects been influenced by other participants, in this case human participants?

MG: Within the Maker culture, the social environment is extremely important, since ideas are born and evolve within a social environment. Kamilė talks about it too. An artist in our century should be given the role of mediator, a person who’d be able to transfer or interpret others’ experiences, or help rethink them. At the same time, an artist as intermediary borrows the thoughts of other participants, which he then interprets and signifies in his/her own work.

BK: How an artwork used in a creative workshop is a starting point for each and every one of us to expand our fields of vision, for everyone who hasn’t thought about it before. In my opinion, the consideration of energy exchange alone (later its intention as well) can affect us so much that we would want to talk about mutual communication, and not only to focus on what’s beneficial to us. Each participant comes with his/her own experiences and views, and in this way brings some new ways of perceiving: we exchange information, news and ideas. And our speculation on possible future scenarios is important. We exchange information, news and ideas between ourselves and other species.

RS: I agree with these ideas about the importance of the role of participants in the workshop. After giving out living organisms, tools and initial instructions, I had no clue what thoughts they would bring to the next meeting, where the path would lead us, or whether the discussion would continue for two months. And now we even have a spring hike planned for the future.

Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

VK: What questions are important or interesting or suitable in this context?

BK: Along with my workshop, I attempted to unfurl the context of ‘Pleasure industry’, the problem of pleasure, and how it can be reflected in our everyday lives. The question I formulated and raised during the workshop was about ‘Plant Trafficking’ (cf. human trafficking), about how plants appear in our environment, plants as trophies, as well as about colonialism. That’s a big part of our economy; it’s interesting how we employ other species for our personal pleasure. Equally important to me was the separation of the human and nature, which today is very often spelt out on social media. That’s odd. After all, we are nature.

KK: One of the main questions I have put is how to find new structures to help us act and be together. If I can recall the importance of the dialogue that Brigita mentioned before, not only between ourselves, but also between us and other species, it’s easy to notice that dialogues spark on several different levels. The investigation is happening through touch, the see-through membranes that make us recognise boundaries between us, and to care about them once they are discovered. Perhaps that also explains my interest in the project ‘Experiencing Lives’, in which mutually experienced material and the topic of discussion created a community made up of microorganisms, as well as another one consisting of virtual discussions and mutual interests.

RS: Looking at the grass swaying in the wind behind a participant’s back (she joined the workshop from a gravel quarry), I proposed a question about our inability to keep quiet during a virtual call. We give or read quite a bit of information by feeling it, sometimes by somewhat mystical means. How can we know that what we think we feel is real? Maybe it’s complete nonsense. To what extent can we trust our senses?

MG: Next to the possible influence we have over other organisms and the influence they have on us, an important problem to consider is how we can experience an artwork through our feelings with the help of these other organisms. By the way, have we successfully shifted our inter-species understanding to some direction with our creative workshops and talk cycles?

RS: In your case, Mindaugas, when an artwork takes the form of yoghurt and is consumed by us, there appears a new array of possible perceptions. Art starts acting within your body, even if you are indifferent to it. In this case, workshops and conversations can serve our ability to make observations, to notice what surrounds and affects us, sometimes completely directly, and yet without us initially knowing where or how to search for it.

Items for participants. Photo: Rūta Spelskytė

VK: What other neologisms have been coined during the workshops? Or perhaps certain old notions have acquired new connotations?

KK: ‘Intermediary atmosphere’, that is, an understanding that words such as ‘environment’ or ‘surroundings’ are powerful aspects that create and sustain life. Hands, air, surface, neighbours have gained new lives, new powers to create stories. James Lovelock and other proponents of the Gaia theory talk about these exchanges quite a lot.

‘Immersive sensors’, as we collaborate with the bread starter, we have to do it on a horizontal level, that is, organism to organism. We ‘think’ and communicate with all our sensors: smell identifies the state of a particular material, colours, sounds talk to us, our hands become the tools for communication, we feel the resistance and the backwards motion of the dough pushing against our kneading movements. Our relations with the world here are not merely made up of the rational apprehension of facts, it is the experiencing of processes, with all the archetypal memory and speculative future.

MG: During this series of events, I thought a lot about adapting to others, and about how it would be possible to interfere in a foreign ‘atmosphere’ as little as possible. It’s been very interesting to see how the anthropocentric pyramid starts crumbling in my mind, and how horizontality becomes increasingly more meaningful. A term you coined Valentinas, the ‘aesthetics of probiotics’, is becoming more significant as well. Haven’t we all been thinking about human aesthetics too much? Shouldn’t some laurels of aesthetics be given to others?

RS: In my case, some already-existing descriptions have faltered. Even one of my Pyrocystis lunula, which I brought to the workshop and presented as seaweed, turned out to be an inter-organism, something between a phytoplankton and a zooplankton, once a marine biologist joined the conversation. This situation in particular led me to investigate other inter-organisms later, such as sea anemones, which look like plants and yet behave like animals; or tunicates, which spend the first part of their lives as larvae, and then later, after eating their own brains, permanently attach to the bottom and continue to grow as plants.

Photo: Rūta Spelskytė

Photo: Rūta Spelskytė

The virtual conversation with artists and creative workshop organisers took place on 28 December 2020.

Participants: Mindaugas Gapševičius, Brigita Kasperaitė, Kamilė Krasauskaitė, Rūta Spelskytė-Liberienė. Moderator: Valentinas Klimašauskas.

This event was sponsored by the Lithuanian Council for Culture and Vilnius City Municipality, and organised by Institutio media.

Link www.facebook.com/events/2811567265753647

More information www.o-o.lt, www.howto-things.com