In mid-May, a major exhibition by the renowned Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson opened in the Kumu Art Museum. The first solo exhibition in Estonia of work by Ragnar Kjartansson (b. 1976) consists of six large pieces from 2004 and 2025. A Boy and a Girl and a Bush and a Bird provides an insight into the oeuvre of one of the most fascinating and idiosyncratic artists on the international contemporary art scene. His art has been influenced by pop music, recent and classic art history and, in a less straightforward way, by political upheavals. Although his works are highly conceptual, full of cultural connotations and quotes, Kjartansson’s oeuvre is truly affective, touching the viewer strongly and very intimately. His exhibition is in Kumu’s great hall, and expands into three project spaces in the permanent collection on the third and fourth floors. Today, we are publishing a shortened version of a talk conducted by the Kumu curator Ann Mirjam Vaikla.

Ann Mirjam Vaikla: Ragnar, you have shown your works in major art institutions, like MoMA and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, in Louisiana’s Museum of Modern Art, in the Barbican Centre in London, and so forth. This exhibition in Kumu is your first exhibition here in Tallinn in Estonia, and is curated by Anders Härm. Congratulations to you, Ragnar, on this outstanding exhibition!

The first theme I brought up with you already a couple of days ago is nature and wildness. There are two reasons for this. Firstly, whenever we think about somebody from Iceland, we just can’t help seeing these epic images of glaciers, erupting volcanoes, thermal waters running in the landscape, etc, but also, the motif of landscape painting is a recurrent topic in your art. In the Kumu exhibition, we see it in the newly commissioned painting series ‘The Weekdays in Arcadia’, but also in one of the project spaces in the long durational video installation ‘Figures in Landscape’. This leads me to ask several questions. How do you relate to nature? Is nature an important part of your everyday life? Why do you keep returning to the motif of landscape painting in your work?

Ragnar Kjartansson: City life in Iceland is so recent. My grandmother, who just died three years ago, was raised in a mud hut between glacial rivers that was so isolated that there were not even any mice there. So for me, through my grandmother and my family history, city life is glamorous. I’m only the second generation living in the city. I want to be a city boy, or a city man now, you know (laughs). So for me, going into this ridiculously beautiful Icelandic landscape is always just ‘paahhh!’, like wow. And then I always feel a kind of connection with my ancestry.

For me, nature has this totally fascinating connection with stories and myths. In Iceland, every hill has a story, either a ghost story or something else. Some Viking killed another Viking there, and so on. The landscape, then, almost carries a cultural field of meaning.

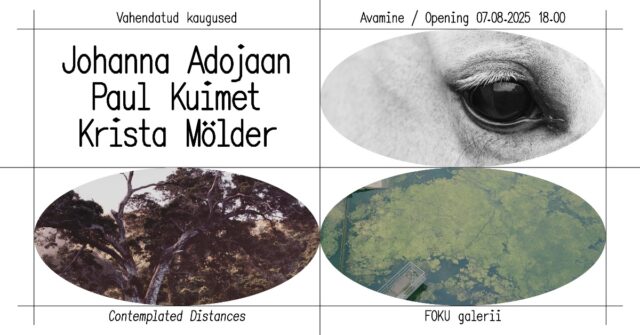

Ragnar Kjartansson, A Boy and a Girl and a Bush and a Bird, exhibition view, Kumu Art Museum, 2025. Photo: Karolin Köster

AMV: Yes, I think in one of your interviews, when commenting on the work The End – Rocky Mountains, somebody asked about nature. Then you said, ‘I don’t understand nature. I only understand culture.’

RK: Yeah, I still stick to that. My mind can’t really grasp a stone on its own, but when I make connections like ‘Ah, your grandmother had a stone like that,’ that’s when I start to understand. Also, for me, when you’re working with nature as an Icelandic artist, it’s almost like being from Italy and saying, ‘Yes, I’m working with themes of the Renaissance.’

One of my main influences is the American artist Roni Horn, who is basically an Icelandic artist. And she consistently understands nature through a cultural lens. Probably no artist knows Iceland better than Roni Horn. And hardly any Icelander knows Iceland as well as Roni Horn does. She’s been everywhere and documented nature: there is always this kind of cultural approach to it. So when working with nature, I almost feel like I am breaking into Roni Horn’s studio.

AMV: I recently met two artists who were doing a residency in Iceland, who were researching glaciers, and they said that historically the farmers in Iceland were sort of angry with the glaciers. That was before the Anthropocene, because the glaciers were still growing and taking over the fields. It seems to me that this narrative, or the position of nature in our culture, is changing, even though Estonians would say, ‘Ah, nature has always been a big part of our identity.’ But if you go deeper, you understand that at the beginning of the 20th century Estonians, for example, didn’t want to identify with nature, because we wanted to become Europeans. And it was only in the 1970s and 1980s, and further on, when nature and forests became such a big part of our identity construct.

RK: It’s very similar in Iceland.

That reminds me of a story where my great grandmother ordered a duvet, and the postman was supposed to bring it, but he fell into a crack in the glacier and died. A couple of years later, he melted out of the glacier along with the horse and all the mail, and the bed linen that was ordered was finally used after all! I have never been on a glacier myself. It seems crazy and can actually be deadly, but glacier tours are a big part of the tourism industry in Iceland.

AMV: Wow (laughs)! I’m now jumping from the theme of nature to the main aspects of your work, and would like to explore how to view and understand your art, which, I would speculate, is also one of the keys to your success. I have interpreted it as a kind of ‘translation’ between different fields and genres of art. You take performance and dance and situate it or ‘translate’ it into the field of the visual arts. When did you realise that this was the right path for you? Why do you place your works in galleries or museums as visual art? Why not create sculptures or installations and present them in the context of the performing arts?

RK: Very good point. I chose visual art because it has a certain playfulness and freedom. Visual art is most free: in the early 20th century it just opened up. No other art form opened as much as visual art. It’s like when you make a film, you must make a film; if you want to do theatre, you must do theatre. But when you do visual art, you can just do whatever you want and call it visual art, which is such great freedom.

We used to play this game: try to make a piece of art that’s not inspired by Marcel Duchamp. Kind of impossible. I’ve tried. But it always becomes a comment on this idea that everything can be art. Of course, there’s also the excuse: it’s okay if it’s bad if it’s visual art (laughs). That’s part of the freedom.

I could go on and on, because I used to be very ambitious. I grew up in Reykjavik, after the Sugarcubes, and I really wanted to be an arty pop star like Björk. And how do you become an arty pop star? You go to art school. They say that all American pop music comes from the soil, but European pop music comes from art school. So I went to art school to become a musician, and then instead I just made art because I found it fun and liberating.

Ragnar Kjartansson, A Boy and a Girl and a Bush and a Bird, exhibition view, Kumu Art Museum, 2025. Photo: Karolin Köster

AMV: I can really resonate with this journey, because I’m trained as a scenographer and came to the visual arts from the performing arts and the theatre world. I think the visual art scene is much more inert, and therefore more political and responsive to social changes, whereas theatre can remain closed off from the outside world.

RK: Also, if you’re doing theatre, there’s always this demand for making people understand. If you make a political gesture in the theatre, it must be clear where you stand in politics. But if you make a political gesture in the visual arts, there is just much more tolerance for being slippery as an eel, you know.

AMV: The other day I read about your work A Lot of Sorrow in collaboration with the American indie band The National. Somebody wrote about it: ‘By stretching a single pop song into a day-long tour de force, the artist continues his explorations into the potential of repetitive performance to produce sculptural presence within sound.’ I just find this ‘sculptural presence within sound’ really precise and beautiful. And I think it’s something we can also experience, for example with The Mercy or No Tomorrow exhibited right now in Kumu.

RK: In No Tomorrow the sculptural aspect also comes through in the movement of sound. The sound is present, tangibly positioned in space.

AMV: Yes. And with the work The Visitors, your most renowned work.

You also mentioned the word ‘politics’. I’d like to take a moment to talk about the feminist dimension, which can also be seen as one of the cornerstones of your work. I believe it’s an important reason why your art resonates with so many of us. Let’s start with a somewhat straightforward question: what does feminism mean to you?

RK: Just very simply, that half of humanity doesn’t have as many rights as the other half of humanity. And I think I have a problem with that.

AMV: That’s a great answer. You’re currently in Estonia, where the gender pay gap between men and women is the highest in Europe. How does the feminist discourse keep informing your creative work?

RK: Honestly, my oeuvre just owes so much to the attitude of the feminist art movement. Like the approach or way to deal with performance and the body and the play with identity. I remember in art school I was in a class about feminist art, and it just blew my mind. To learn about Marina Abramović and all these fantastic artists that just suddenly represented another voice in art history. I found it very interesting to play with this idea of identity. Nowadays, the theme of identity is very prominent in art, and sometimes it can become … a bit too intense. Just the way we focus so heavily on identity today can sometimes feel a little … fascist, you know?

In short, I was fascinated by feminism and studying feminist art, and by the realisation that the problem lay in my identity. I just found that so fascinating, that everything I did was a part of the problem. So I began to make use of my privileged identity as a white freak, and I still think about it a lot. What’s interesting is that, for example, when I perform in the US there’s often this attitude ‘Why do you call yourself a feminist? You’re a man, you shouldn’t do that,’ which is a complete misunderstanding.

And Iceland also changed very fast. Iceland suddenly had a female president in the 1980s, and then there came the women’s party, and they became powerful in the parliament, and then they disintegrated into other parties. That was their goal, to quietly blend into other political parties, so that those parties would start to care more about feminist issues … That’s why now, within the conservative, farmers’ and social democratic parties, each has its own feminist school of thought. And the prime minister, the president, the bishop, the chief of police, they’re all women in Iceland. Being in that kind of society shaped me a lot.

Ragnar Kjartansson, A Boy and a Girl and a Bush and a Bird, exhibition view, Kumu Art Museum, 2025. Photo: Karolin Köster

AMV: Yeah, you’ve also said that ‘Feminism is like a constant practice one needs to attend all the time.’ I really like this idea of ‘a constant practice’.

RK: That’s exactly it, because given my background, I would be a typical chauvinist by all accounts. If I were to let myself go and just be myself, I would simply be a chauvinist. It’s almost like not going to the gym … (laughs). So you kind of have to be very aware of it. For example, I’m not saying that male chauvinist pop songs are bad, they can be really good. But when you hear a pop song on the radio, you just have to kind of realise, ‘This is a chauvinist pop song. I mean, I like it, but it is what it is.’

AMV: I just remembered now you even went to the Reykjavík School of Housewives. What did you do there?

RK: Yeah, it’s still going strong.

I learned how to be a good woman there. It’s now called the School of Home Economics in Reykjavík, but it used to be called the Reykjavík School of Housewives. I was the first man to enter that school. So you can imagine what an adventure it was. As the only boy among girls, I learned to sew, cook, and do all sorts of other things like that.

Now it has been modernised, but when I went to it in 1997 it was basically like stepping into the 1950s. And the headmistress was a wonderful person, but from a different era. When I was starting this course, she said: ‘Ragnar, I have to tell you, on Thursdays we usually teach cleaning. And if you find it too degrading, it’s okay, you don’t have to show up.’ That experience also probably made me very aware of what my mother and my foremothers had to go through. Like you kind of see this world of obedience, but also all the gorgeous things that are created within it. And I think that’s also why I got into art school. I had a shit portfolio. But they were like, ‘Wow, you went to housewives’ school, that’s impressive’ (laughs).

AMV: This is in a way what you’re doing in your art. You use your own identity with the privileges you have to give space for others. I can see it clearly in the main artwork here No Tomorrow. It’s also very important for me that it’s a collaborative piece. Someone from the audience asked why there are only women there, but to me it seems meaningful simply to create a visual world where women exist at all.

RK: Yeah. And because I’ve been working so much with the male identity. Of course, it’s a bit embarrassing, but I like clichés. One of my favourite works is The Cliché is the Ultimate Expression Collaboration by Magnus Sigurdarson.

In No Tomorrow we’re, of course, simply talking about white women wearing jeans. There’s something unsettling about that, but I actually like finding disturbing elements in clichés. I like it when beauty is sometimes a bit cruel.

AMV: Let’s move from feminism to colonialism. This topic appears in one of your early works made in 2003 called Colonization. It’s one of my favourite works of yours. I think you have a very interesting take on how you’re dealing with this super-cliché image of Danish colonialism. Because I guess it could also be speculated whether Iceland was ever a colony of Denmark. The situations of Greenland and Iceland, as I understand, were very different. And are still very different nowadays. Iceland does not depend on Denmark, while Greenland does. Could you tell us more about this piece?

RK: Colonialism in general is, of course, a brutal problem of humanity, and always has been. It’s part of the patriarchal problem. But I mean, you Estonians have had to deal with Russian and German colonialism. We had to deal with Danish colonialism. And I just find it interesting. Colonization is a work where I play an Icelandic peasant, and this actor, Benedikt Erlingsson, plays a Danish merchant who’s just beating me up and is just being horrible to me, but it’s all set in a very theatrical setting. And he’s just saying: ‘You piece of horse shit, you piece of pig shit,’ and just kicking me. It becomes comical, it’s very silly. It’s almost like Benny Hill.

I made this piece when I was a young man. I was drinking heavily in Copenhagen, and I went to the Vega Club, and I couldn’t get in, so I kicked the door, and the glass of the door broke. The security guards took me down and called the police. I found it interesting that instead of being ashamed, I was a drunk bastard and said things like ‘Okay, is this how you’re gonna treat me? Are you gonna treat me like you treated my forebears?!’ I fully took on the postcolonial victim role. And this work was sort of a play on this colonial victimhood of Icelanders, because for Icelanders it’s a very important part of our national identity: that we were victims of Denmark … This narrative was very important for our national identity and bringing us independence. But when you look at the reality of history, it was mostly Icelandic landowners who basically treated people as serfs, and people had no rights. And the Danish king was trying to fix that, to make people have more rights, but Icelandic farmers were vehemently against it.

It’s also interesting that we learn so much about it in school: Danish colonisation. But the Danes kind of have no idea. We have a lot of shared history, but it’s not taught in Denmark. I don’t think it’s the deliberate erasure of history, but I just find it interesting. And it was also interesting to show this piece in Denmark.

Ragnar Kjartansson, A Boy and a Girl and a Bush and a Bird, exhibition view, Kumu Art Museum, 2025. Photo: Karolin Köster

AMV: Why I also wanted to bring this work up is because of this notion of building your identity on victimhood. I believe this also creates a sense of recognition here in Estonia and Eastern Europe. In a way, it seems that overemphasising the victim role status hinders empathy, and consequently the broader development of society.

RK: Yes, everybody likes to identify as a victim. I mean, Donald Trump wants to identify as a victim. I find it most interesting when oppressors, you know, like the Americans, feel themselves as victims. And of course, the whole Nazi ideology was all about being victims.

AMV: Showing the work No Tomorrow here at this moment where we are right now, after three years of war in Ukraine, seems like a gesture of resilience, because it reminds the viewer that it is very important to attend to the beauty of daily life, to the dance and the joy, and so on.

RK: Yes, exactly. Sometimes it feels like there’s so much to say that, at the same time, you don’t know what to say any more.

AMV: What are your plans for the future? Would you like to share a bit about the direction you’re heading in, and the themes you’re working with?

RK: I’m currently working on several themes and projects. For example, one involves the work of the sitcom writer Anne Carson: it will be a sort of endless sitcom, a continuously repeating comedy scene that we’ll be filming next year. It will be six hours long. I’m experimenting there with the repetition of the situation.

And then I’m working on a piece which has a nice title in Italian, ‘Domenica Senza Amore’, which translates into ‘Sunday without Love’. That’s going to be in Italy in September. It’s a musical thing based on a song by a German guy called Rocko Schamoni, who wrote this song in the 1990s. I love this song so much, but nobody knows it. And I sent him a question if I could use this song for this work. And he was just like, ‘What the hell, why do you know this song?’ Nobody likes this song. But it’s a good song. So it’s in German, but in English it goes like this: ‘You have to live without love, love is not good for you. Stop all this longing, looking at stars. Stay on the ground and listen to me.’

AMV: Wow! This song, and you coming to talk with us, felt like yet another act of generosity, Ragnar. Thank you! I’d like to finish with that thought.

RK: I also want to thank all of you for your openness. It has been truly wonderful here. I’m incredibly honoured to show my work at Kumu. Shout out, thank you, mic drop!

Ragnar Kjartansson, A Boy and a Girl and a Bush and a Bird, exhibition view, Kumu Art Museum, 2025. Photo: Karolin Köster