At the beginning of 2020, several art institutions in Finland established a new post in their organisations. They hired eco-coordinators to evaluate their carbon footprint, and develop strategies for reducing climate emissions. For example, Helsinki Art Museum HAM, Espoo Museum of Modern Art Emma and the Kone Foundation created such posts in a short period of time. Saara Korpela was hired a year ago jointly by four institutions, IHME, Frame, HIAP and Mustarinda. Airi Triisberg interviewed her to discuss the outcomes and impact of her work. The interview was conducted in December 2020, and was initially published in the Estonian cultural weekly Sirp.

Airi Triisberg: I find the idea of hiring one employee for four institutions at the same time very interesting. I assume the issues they deal with are very similar, and the knowledge gathered for one institution can easily be transferred to others as well. However, it seems that most of the time you work with each organisation individually. What are the main issues in your work?

Saara Korpela: I have been doing slightly different things for each organisation. They are at different stages in ecological practice, and have different needs. Mustarinda has the longest history of working specifically with ecological issues. It runs a residency in Hyrynsalmi, which is 250 kilometres from the Arctic Circle, and is one of the areas with the highest snowfall in Finland. They have a 700-square-metre building, and energy plays an important role in their activities. They have experimented with different technologies, and for a period they even ran their own windmill. Such technical solutions require investment. Mustarinda currently uses wind-power, a geothermal heat pump, and solar panels to produce the heat and electricity for the needs of the house. Their building is not completely carbon neutral, but it produces very low emissions. My role has mostly been about communicating what they are doing. I wrote an article about their energy solutions,[1] and another one about their carbon footprint.[2] I have mostly been learning from them, rather than suggesting changes in their practices.

Mustarinda energy system. Image by Pauliina Leikas / Mustarinda.

AT: Mustarinda is quite an exceptional art institution, because they have been able to make changes in the energy system of the house themselves. Most art institutions work in urban rental spaces, where they can hardly choose what energy sources to use. How are the other three organisations dealing with the question of energy?

SK: Heating is a major factor in the ecological footprint, but we cannot do much about it because we cannot control the decisions made by the energy company. There is a big contradiction between the ecological impact and our ability to influence a situation.

The offices of IHME and Frame are so small that electricity and heating form a very small part of their emissions. It is more relevant for HIAP, which also runs a residency programme. They operate several buildings that belong to the City of Helsinki. They are currently developing an intelligent heating system, in cooperation with the Governing Body of Suomenlinna Island. It is a joint project, and HIAP has also invested in it. The project includes installing new thermostats, which are linked to the weather forecast system. If the weather is very cold one day, but the temperature will rise the next, the heating system will take that into consideration, and heat less. It will bring an estimated 15% reduction in heating emissions. It has taken three years to make this happen; we are almost finished now. It is something very tangible and concrete.

AT: This is a very interesting example in the light of what you were saying about our ability to control and make choices. There are choices we make individually within the existing limitations, such as what to eat or buy. And there are choices we cannot make without changing existing conditions, which is essentially a political activity. Our individual influence on political processes is limited. An intelligent heating system seems to be somewhere between the individual and the political, it expands existing constraints by the use of technology.

Your main task has been to calculate the carbon footprint of art institutions. How did you do that, and what are your key findings?

SK: We started by measuring different aspects: kilowatt hours of electricity and heating; kilometres that were flown long distance, medium distance, short distance; kilometres driven by car, bus, train; travelling by sea; number of hotel nights and the price; list of purchases (furniture, laptop, printer, some 20 items in this list); the amount of money spent on phone calls and the internet; money spent on cleaning; food offered at events; the amount of coffee, tea, and other drinks; kilograms of waste in the office. When events took place at other venues, then the duration in hours, and the square metres of the space.

Based on these numbers, I used the calculator of the project Hiilifiksu järjestö (Carbon-smart organisation).[3] Different calculators use slightly different measurement methodologies, and the standards are evolving as we speak. That’s why we have kept meticulous records of the input data, and can do the calculations all over again with another calculator if necessary.

The outcome is pretty much what we already know. It’s surprisingly evident that flights are the main culprit behind emissions. Reducing the carbon footprint of the art world requires reorganising modes of travel for artists and curators, and the transport of artworks.

In the light of this knowledge, Frame has decided not to fly inside Finland. The staff at HIAP has more or less stopped flying; they have reduced travel emissions by 86%. HIAP is following three guidelines: travelling slowly, travelling less, and travelling closer.

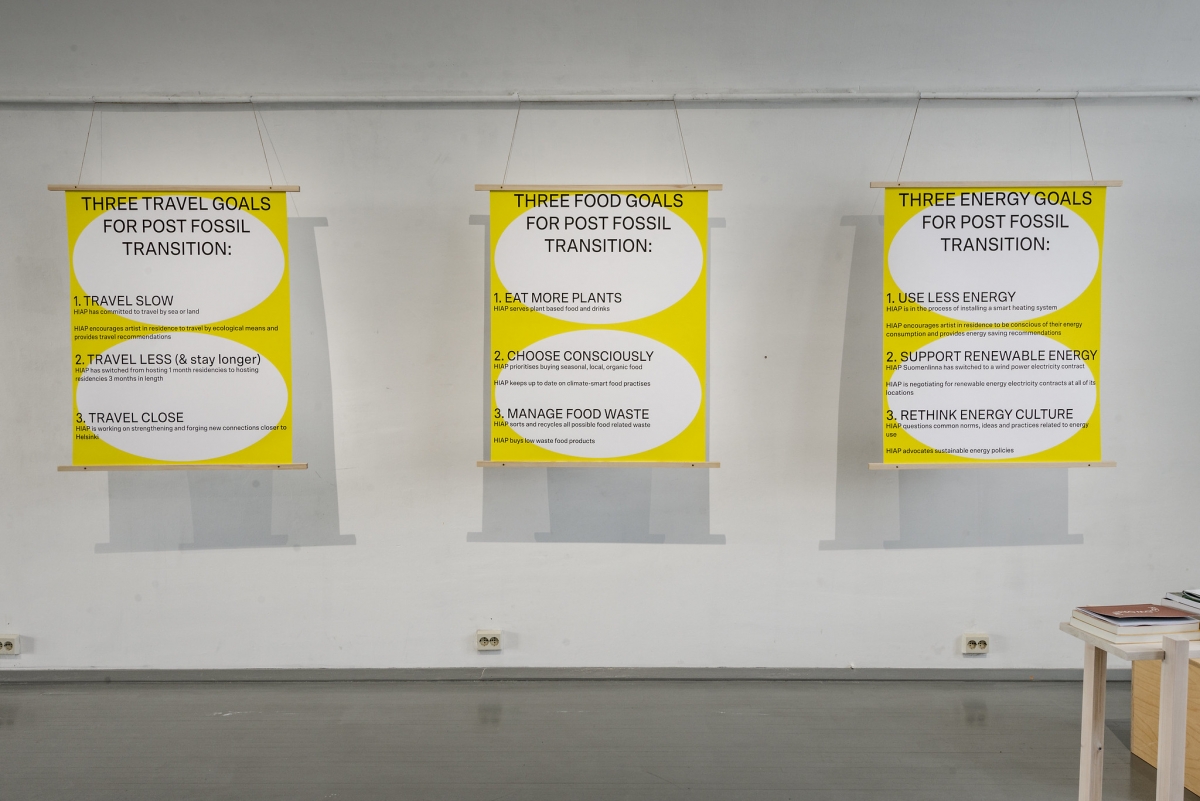

The posters present the important key changes at HIAP regarding the three focus areas of the ‘Post Fossil Transition’ project: Travel, Food and Energy. The posters were designed by Dana Neilson (based on HIAP visual identity by Tsto). Photo by Sheung Yiu.

AT: The practice of travelling slowly should also be discussed in connection with material conditions in the art world. For example, the cost of slow travel is not only the ticket, which might be more expensive for a train than for an airplane; you also need to eat during the two or three extra days. When I take a bus from Tallinn to Berlin, I need to stop for two nights and sleep in a bed, because my body cannot endure a 24-hour bus trip. It seems to me that changing travel habits in the art world also requires some change in how institutions and funding bodies deal with their finances.

SK: Frame gets support from the government, and they are bound by the Finnish State Travel Regulations. These are based on two principles: you should travel as cheaply as possible and as fast as possible, which means that the current regulations instruct all state-funded bodies to prioritise air travel. Frame has launched an initiative to change these regulations.

When it comes to individual art practitioners, all four institutions believe the responsibility should not be on the shoulders of one artist. For example, Mustarinda, which is located in the far north, provides artists in residence with slow travel support. Artists receive extra money in order to choose not to fly.

The question whose responsibility it is to choose not to fly has been a big and important discussion in Frame as well. Frame awards many grants. Can they require artists not to fly? How can the ecological component be taken into account when awarding grants? We have not made any decisions yet.

This also raises broader questions about what decisions an organisation can take, and what decisions belong to the individual person. For example, eating meat or vegan food is a personal decision. It is not going to be calculated or measured in the organisation’s carbon footprint. I only measure the footprint of activities that are financed by the organisation. An employer cannot tell you what to eat for lunch; you buy it or cook it yourself. The question is, how can the organisation support or encourage the decisions you make personally. I have not yet reached a conclusion here.

AT: There are many different scenarios that can arise between an art institution and an artist. My colleague Siim Preiman from Tallinn Art Hall told me that when he curated the exhibition ‘The Art of Being Good’ he encouraged artists to refrain from flying; but some refused. I also talked to an artist who participated in the exhibition, who considered it an absurd request from the curator, and even as pressure exerted by the institution. On the other hand, I also know artists who are pressurised by institutions into choosing the cheaper option of flying due to budget constraints. There is no clear protocol with regard to these questions. Sometimes the artist pushes for ecological solutions, and sometimes the institution makes demands.

For me, it was a big surprise to learn that the difference between flying and travelling by ferry is much smaller than I thought. I recently learned that there is one ferry in the Baltic Sea, Viking Grace, which is newly built and produces much less emissions. I realised that it is not enough to know the general differences between flying and sea or land travel; we should also be well informed about particular travel companies, and even vehicles. I don’t feel competent enough to make such decisions, and I suspect that neither do most art institutions have enough knowledge.

SK: It’s true that you need very specific knowledge to make these choices, and it is too much to ask from individuals. The existing calculators might present conflicting information, because they use different methodologies. Some calculators only record emissions that come directly as carbon dioxide from fuel. That number should be multiplied by at least two, to include emissions from building the aeroplane and producing the fuel. When a plane flies in the upper atmosphere, then there should be a multiplier of 5.7. But as passengers, we do not know what percentage of certain routes is flown in the upper atmosphere. Other differences are related to allocation: take, for example, a ferry, which has both passengers and goods: how should the emissions from a journey be divided, according to the weight or the price paid?

It’s easy to be paralysed by conflicting information, but we live in a time when we need to act, not freeze. That’s why it’s good to remember that we already know for sure that we need to reduce our impact on the planet. We also know for sure that we need to cut travelling (especially flying and driving), meat eating and heating.

AT: Your finding was that the biggest source of carbon emissions in the art sector is travel and transport. However, these four institutions that you have evaluated have very specific profiles. HIAP and Mustarinda are residencies, Frame enables mobility among art practitioners. IHME is actually the only organisation that is mainly focused on the production of art, but it does it on a fairly small scale. I wonder if the result would have been the same in the case of bigger exhibition institutions. Nowadays, everybody talks about travel, but there is much less talk about the materials used in the production of art and exhibitions. For me, this part of the equation remains obscure.

SK: I think it’s an obscure area for everyone, because we don’t know what the carbon footprint of different materials is. It’s hard to find a reliable database that is public and freely accessible. There are some open databases, but they’re about construction materials. I suspect that most emissions from art come from energy and travel, and not the materials. If you don’t use cement or steel as your materials, I wouldn’t worry about the materials at all. Instead, I would think about the flights and the venues connected to the works of art. For example, the environmental coordinator at Helsinki Art Museum (HAM) found that their main sources of emissions were heating and transport.

‘Mire Reception’ by Saara-Maria Kariranta, Riikka Keränen, Hanna Kaisa Vainio. The installation contains an artificial mire made of plastic, organic material and water, and was presented at the ‘Post-Fossil Show’, HIAP Gallery Augusta in 2020. Photo by Sheung Yiu.

AT: What have been or will be the actual changes resulting from your work?

SK: With Frame, we are now working on a roadmap to get emissions down. We know the amount of emissions for last year, and are considering what steps need to be made in order to become carbon-neutral. We are thinking about whether it would be possible to organise some visitor programmes online. Much can be done, but we haven’t taken those decisions yet.

HIAP and Mustarinda have been developing a three-year project called ‘Postfossil Transition’ together. Their three core themes are energy, travel and food.

IHME has been in a more profound transition period. Three years ago, they started rethinking their activities. They realised that climate change is important today globally, because it affects everything. The core of IHME is about uniting art, science and the climate. One way to reduce emissions is to slow down. Instead of organising a festival, IHME now hosts just one work of art every year. They switched from using fossil energy to wind energy. The ecological aspect has been integrated into their strategy and everyday work at different levels.

One strategy is also going digital, for example, not printing a catalogue but putting it online. However, we should also consider the digital carbon footprint. More online traffic means more energy consumption. At the moment, we don’t have a clear figure for the digital carbon footprint. There are different studies: some say it’s tiny, and some say it’s huge. I believe the truth is somewhere in between. But it’s reasonable to bear in mind that different ways of transferring data have different footprints. Text is very energy efficient, then comes sound, then images, and finally video. A video conference produces most emissions. It’s perhaps worth reminding ourselves that writing an email is better than a quick video call.

‘Listening through the Dead Zones’, a sound installation by Jana Winderen produced in collaboration with IHME. The Helsinki Rowing Stadium will be the venue for the project in August 2021. Photo by Veikko Somerpuro.

AT: The Covid-19 pandemic has forced us to change our behaviour in many ways. Air travel has been largely replaced by video conferencing. Many art institutions are organising their public programmes online. During the first wave in the spring of 2020, exhibitions were mediated to audiences through virtual tours and viewing experiences. Meanwhile, more exhibitions have been constructed for online experience. It seems to be a new trend. Is that the future we are striving towards? Does this experience pose new questions for you? I’m not very glad at having even fewer reasons to close my computer and disconnect from the Internet …

SK: There’s a risk that we think we are building a system for video conferencing that causes less emissions, but we still have those huge museums and galleries, which need to be heated. As a result of the pandemic, both these systems are running, so we have more emissions. After the pandemic, we will probably have more video conferencing and online programmes, but we will also be flying again. I’m not too optimistic about the future. I’m quite worried about the possible rebound effect.

[1]https://mustarinda.fi/blog/mustarinda-energy-system

[2]https://mustarinda.fi/blog/mustarinda-carbon-footprint

[3]https://blogs.helsinki.fi/hiilifiksu/