Excerpt from Chapter 5: Feminine genealogy. Separation and convergence

Jana Kukaine. ‘Daiļās mātes. Sieviete. Ķermenis. Subjektivitāte’ (Beautiful Mothers. Woman. Body. Subjectivity). Rīga: Neputns: 2016 [in press].

Ieva Epnere. Inese. From the series Mothers. 2011-ongoing

[..] One of the themes of contemporary feminist art is devoted to the study of the mother as artist, both by becoming aware of various “underwater rocks” and also by looking for validating and motivational potential for art in this complex situation.[1] In the traditional binary system of thinking, woman—and especially a mother—is incompatible with the idea of a creatively generative being, no matter whether it be writing or art or some other field. In patriarchal Western culture, creative work is linked with the concept of paternity—the author of a text or work of art is the man, the progenitor, the creator, the aesthetic patriarch, whose “pen is an instrument of generative power like his penis”.[2] Women do not write or paint; instead, they are written about and painted. This dichotomic separation, in which creative work is understood as the privilege of a rational and autonomous being, is reinforced even more by motherhood, which is traditionally associated with nature, the corporeal, the instinctive and the emotional.

As literary critic Emily Jeremiah has noted, the acknowledgement of the mother as a creative individual means to seriously challenge the paradigm of creation and demand that significant changes be made to the understanding of the concept “author”. In her view, there is a certain analogy—instead of an irreconcilable contradiction (either a book or a child)—between the practice of motherhood and creative work. This aspect has already been emphasised by Julia Kristeva , who sees a semiotic, ancestral, pre-Oedipal motherly impulse in each creative action. A similar thought is also expressed by Hélène Cixous in her famous work The Laugh of the Medusa, in which, through an analysis of the peculiarities of female writing, she has formulated the memorable notion that a woman writes “with white ink”.[3] This can be understood as an allusion to woman’s invisible contribution to the history of writing as well as—and which is more likely, regarding the tendency of Cixous’ text—an attempt to express a new paradigm of feminine writing that is based on mother’s milk. As a result, motherhood, feminine genealogy, corporeal experience and sensuality become the basic indicators of a creative work.

The artist–mother complicates the traditional separation between the public and private, consciousness and the body, the mind and emotion, culture and nature. A mother’s daily life, as well as the creative activity of an artist, must be understood as a relationship-based practice in which a number of variables play significant roles: the historical context, intertextuality and intersubjectivity. A work of art (just like the practice of motherhood) is not something autonomous, “pure” and universal; instead, it is situative and dynamic. If relationships, bonds and a certain amount of dependency are an essential part of motherhood, then a piece of artwork and the artist are also in a similar, unpredictable situation that cannot be fully controlled. As a result, according to Jeremiah, by including the motherhood experience in our understanding of an artist, we gain a position from which we can critically examine the deep-seated Western image about the independent, secluded and self-sufficient individual who creates independent, secluded (in terms of meaning) and self-sufficient works of art. Sensitivity, openness and an orientation towards establishing relationships is at once a precondition for both a mother and an artist, and this indicates the existence of a body-based, often contradictory, unstable subjectivity in the process of creation.[4]

Of course, these theoretical considerations often cannot solve the practical difficulties that arise when trying to combine the raising of children with creative work. Griselda Pollock has aptly noted that, due to various social factors, the most common images of artists—a misunderstood loner, a bohemian carouser, a collector and researcher of strange things—are often not compatible with a mother’s circumstances and possibilities. Female artists in Latvia are also talking about these same difficulties, which was confirmed by the exhibition Sievietei būt (You Art a Woman). Of the artwork displayed there, I wish to highlight two pieces: Vivianna Maria Stanislavska’s Sieviete (Woman) and Elīna Ģibiete’s textile work Dienas moments (Moment of the Day).

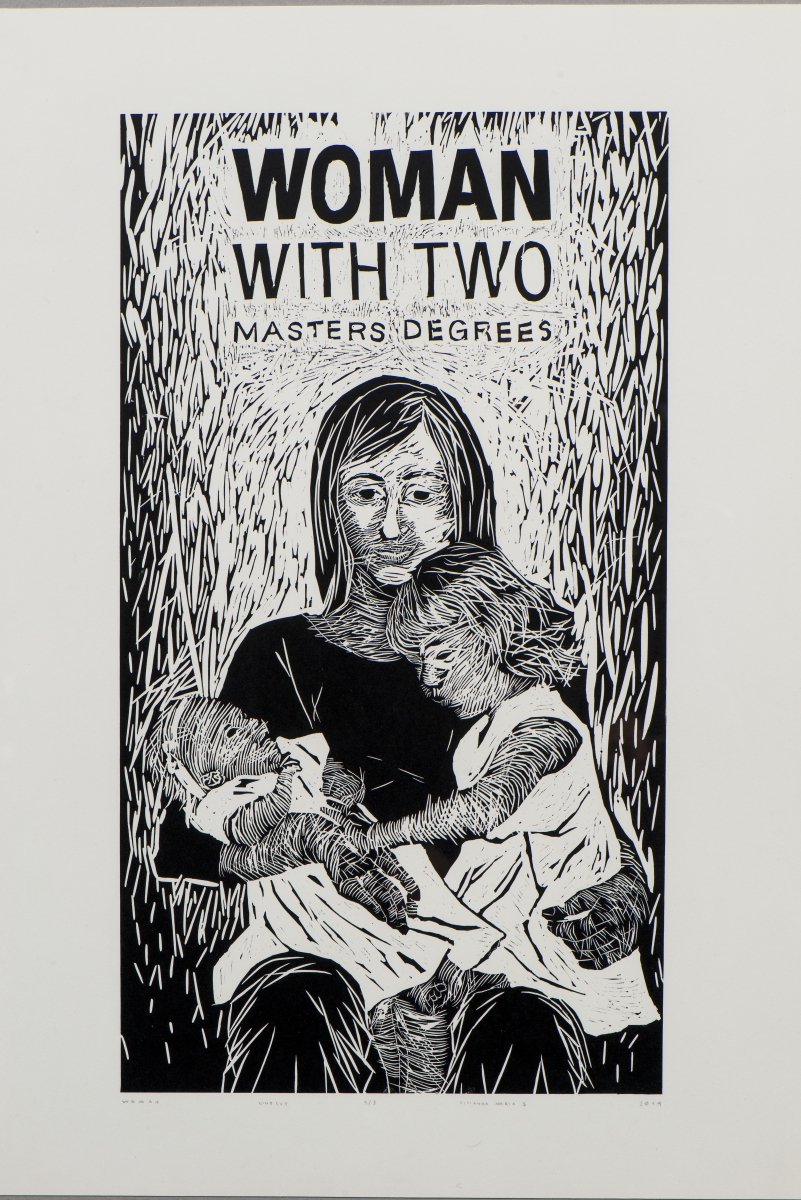

Stanislavska’s work actually needs no additional comment—its story line and precise caption are explanatory enough. In developing the theme, she chose a reference to the classic iconography of the Madonna, expressed in a contemporary style—the mother depicted in the work of art does not resemble Our Lady but instead a regular young woman, perhaps a college student who must try to find balance between obtaining an education and raising a child. The child is not an otherworldly event taking place outside of time and space; instead, it is the totality of real worries and anxiety, sleepless nights, lectures, tests, empty plates, skinned knees, tears, horseplay, laughter and loving touch.

Vivianna Maria Stanislavska. Woman. 2014. Photo: Normunds Brasliņš

Elīna Ģibiete. Moment of the Day. 2014. Photo: Normunds Brasliņš

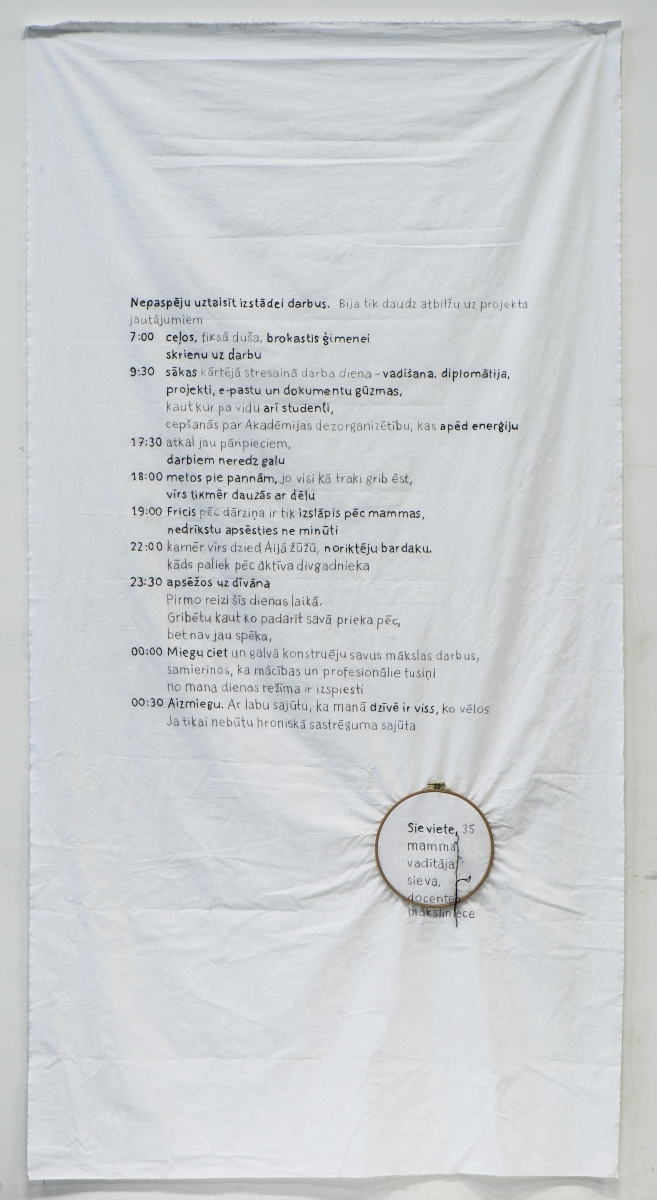

Ģibiete’s work Moment of the Day (2014) reveals the intense flow of the artist’s daily life, which leaves no time for creating artwork or doing anything “for her own pleasure”. Ģibiete describes her daytime work as “stressful”, and evenings with her family are also always busy, in spite of the fact that the children’s father also participates in child care duties. Only six and half hours remain for sleep. In a round frame, Ģibiete has listed all of the roles and responsibilities she must fulfil during an average day, of which “artist”, being the least imperative, remains outside the “frame”.

Moment of the Day resembles another project, namely, one made by Margaret Harrison, Kay Hunt and Mary Kelly in the 1970s and based on a study of female workers in a metal box factory in London. The study, Women and Work: A Document on the Division of Labour in Industry, included interviews with the workers, information about their daily routines and general statistics. For example, in it we learn that, just like Ģibiete, a 21-year-old worker named Joan Martin combines a full-time job with caring for a young child, and after work both young women devote time to preparing meals and general cleaning and housekeeping duties. They both receive approximately the same number of hours of sleep, and their daily routines do not allow for any “free time” or “time for themselves”.[5]

The comparison is quite surprising. How can it be that the daily routine of an artist, assistant professor and leader with a higher education living in the 21st century does not differ much from that of a considerably less educated factory worker ten years her junior and living more than 40 years ago in London? Where is there room for the myth of the creative genius who makes artwork in the quiet seclusion of her studio? Where is there room for the advantages provided by education or the accommodating attitude of today’s labour market towards women’s needs, such as allowing them to work a shorter day? Would their daily routine change if women’s level of income increased or if fathers participated more in child care? For what reasons has an artist chosen to engage in a number of other professional responsibilities in addition to her creative career? These questions form a fertile platform for a critique of the labour market as well as the institution of the family, and they also invite contemplation about the factors determining the cultural environment in Latvia today and, especially, a creative woman’s situation within it.

But the critical potential of Ģibiete’s work is tempered by its final statement, namely, that when the artist falls asleep at night, she feels a certain sense of fulfilment: “I fall asleep. With the good feeling that I have everything I want in my life. If only I did not have this chronic bottleneck feeling.” This last comment is slightly confusing for several reasons. Firstly, can a subjective feeling of satisfaction (assuming that it is genuine) reverse obvious problems that have been created by decidedly non-subjective conditions? Secondly, if a “chronic bottleneck feeling” is really the biggest problem, then the factors causing it should be sought—I assume they would be the same factors that in large part influence all of our daily marathons. And finally, such a statement contradicts the content of the work of art, which shows that the artist lacks time not only for “studies and professional parties”, and not only to do something “for her own pleasure” or just quietly sit on a sofa, but also, strictly speaking, for art. I do not know what Ģibiete’s reasons for such a conciliatory, reconciling gesture were; perhaps it is based in a desire to distance herself from the image of the “angry feminist”, thereby remaining in the comfort zone of a “pleasant woman satisfied with life”. Also, interestingly, the tension that Moment of the Day inevitably creates is to a certain extent balanced by the fine embroidery, which nevertheless required time and peaceful concentration to complete. The sewing ring left in the work of art not only symbolises the “battle” between the various competing roles a contemporary female artist must juggle; it is also a practical allusion to the piece of handiwork that has been left unfinished due to some unexpected thing that has averted the artist’s attention (a situation that, considering the sewer’s oversaturated daily schedule, is not at all difficult to imagine).

Another work of art that has brought the problematic situation of sister artists to the fore is Ieva Epnere’s photography series Mammas (Mothers, since 2011). The series consists of portraits of well-known local women from the creative professions together with their children, and each portrait is accompanied by the women’s comments about the opportunities, advantages and unavoidable disadvantages and sacrifices related to combining family and career. In them, we hear about truths that the women’s children have helped them to understand; but the women also voice concerns about whether the time they have devoted to child care has irreversibly subtracted from their professional lives or ability to work creatively. The women tell about the feeling of a “postponed life”, the responsibility and also the immense fulfilment that the presence of children brings. The stories are deeply personal, and therefore Epnere has not wanted to publish them in any form of media. To a certain degree, this shows that speaking openly about such themes in Latvia is, for some reason, uncomfortable—the psychological and practical difficulties encountered by creative mothers do not really fit with the image of a “good mother” or with the image of a successful actress, film director or artist. Epnere has photographed the women without pathos, avoiding a romanticisation or idealisation of her subject. Instead, she provides a realistic (that is, believable) and sometimes even dramatic portraiture of women and children.

[..]

The various modalities of motherhood that appear in the work of female Latvian artists correspond to the character of the experience of motherhood—it is multi-faceted and ambiguous. The more clearly women articulate their experience, without fearing to also talk about the difficult, despairing, sorrowful and disappointing moments, the fuller the picture and the more authentic the features on the Madonna’s contemplative face. After all, an honest articulation of women’s experiences will lead to fruitful discussions and the transforming of actual motherhood practices. At the same time, the prejudice that a mother’s and parents’ role is “too narrow” or “too specific” a theme for art would be surmounted, thereby allowing various aspects of experience to expand the field of reflection in art.

Ieva Epnere. Guna. From the series Mothers. 2011-ongoing

Ieva Epnere. Kristīne. From the series Mothers. 2011-ongoing

[1] Jeremiah, Emily. Troublesome Practices: Mothering, Literature and Ethics // Journal of the Association for Research on Mothering, Volume 4, Number 2, 2002, pp. 7–16. Even though the author of this article examines feminist literary criticism, I believe that the trends touched upon also describe quite precisely what is happening in the sphere of art and art criticism.

[2] The paradigm of patriarchal creativity is thus described by Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar in The Madwoman in the Attic (1979). Quoted from: O’Reilly, Andrea. Introduction // From Motherhood to Mothering, p. 17.

[3] Cixous, Helene. The Laugh of the Medusa // Signs, Vol. 1, No. 4, 1976, p. 881.

[4] Jeremiah, Emily. Troublesome Practices: Mothering, Literature and Ethics // Journal of the Association for Research on Mothering, Volume 4, Number 2, 2002, pp. 11–12. It should be noted that a traditionally understood criticism of the subject of a work of art was already begun by 1960s conceptualism, which offered new platforms of expression for feminist art. But in the 1960s and 1970s the standard in art was still defined by the implicitly accepted masculine subject, which perceived the artistic and the specifically motherly as two mutually exclusive quantities. See: Liss, Andrea. Feminist Art and the Maternal.

[5] See: Conceptual Art / Ed. by Peter Osborne, p. 156.