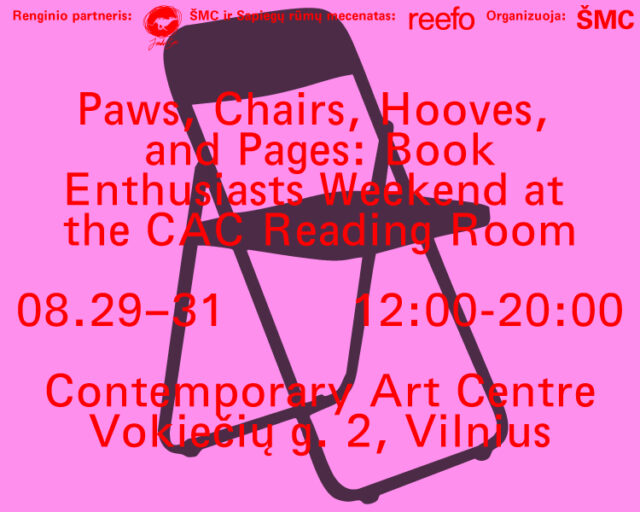

The Radvila Palace Museum of Art, one of the flagship branches of the Lithuanian National Museum of Art, has a prominent strain dedicated to historical overviews of unofficial or dissident art in its exhibition agenda. The most recent show, ‘NSRD: Information About A Transformed Situation’, curated by Māra Traumane and Māra Žeikare of the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, is a vivid example of that. Yet it is not your regular exhibition of underground art, as its sheer multitude of layers and aspects is almost overwhelming, and resists being contained in a familiar consistent narrative of ‘silent’ opposition to the authoritarian system.

Built around the diverse activities of the masterminds behind the Latvian music and art group NSRD (Nebijušu sajūtu restaurēšanas darbnīca or Workshop for the Restoration of Unfelt Feelings), Juris Boiko and Hardijs Lediņš, and their various fellow-travellers, the lush display (credit to the architect Gabrielė Černiavskaja) is bold, and occasionally looks like an avant-garde Utopia come true. But who are the recipients of the information transmitted by the exhibition? This question has stuck with me since visiting the show, and has also led me to ponder some related concerns, namely, where does the NSRD stand in relation to historical (Western) avant-garde, and happening or action-oriented art groups active around the same time (the late 20th century) in the region of Central and Eastern Europe, particularly in the neighbouring republic of Lithuania. Fragmentary insights related to these questions may shed a light on the local socio-political differences in the various countries of the socialist bloc, and about the ties (or lack of them) between those countries’ unofficial art milieus. What feelings were unfelt where, and can they be restored in a different place and context?

Exhibition view, ‘NSRD: Information About A Transformed Situation’, Radvila Palace Museum of Art, Vilnius, 2024-25. Photo: Gintarė Grigėnaitė

Exhibition view, ‘NSRD: Information About A Transformed Situation’, Radvila Palace Museum of Art, Vilnius, 2024-25. Photo: Gintarė Grigėnaitė

Interest in 20th-century art groups in general seems to be on the rise recently, and even the seemingly all-too-familiar subject of Surrealism has been given a thoroughly updated and expanded reading in ‘The Subterranean Sky’, a display of historical and contemporary works at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 2024 dedicated to the centenary of André Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto. While the NSRD is perhaps not a direct descendant of historical Surrealism, some of the avenues of Lediņš and Boiko’s psychoactive explorations, particularly their literary output, such as the 1977–1978 novel ZUN, seem kindred to it in their reliance on absurdity, automatism, non-linearity and paradox. On the surface, the universe of the NSRD looks like a bright, if somewhat weird, place, but the breath of the uncanny can be felt beneath the surface throughout.

Moreover, what can be pointed out as a shared trait of Lediņš and Boiko’s oeuvre, and that of the classic Surrealists, as well as later artists they influenced, is a penchant for mystification, myth-making and psychedelic occultism. Many of the Latvian artists’ documented individual and collective actions involving their close associates like Inguna Rubene and Imants Žodžiks, such as the periodical situationist walks along the railway tracks to the secluded neighbourhood of Bolderāja, or eclectic multi-media stage performances, are ritualistic by nature and are marked by a kind of post-industrial esotericism that brings them close to the 1970s British music and performance collective COUM Transmissions, who were themselves heavily influenced by Surrealism and Dada, among other things. Besides, the fact that Lediņš himself is often perceived as something more of a legend than a real-life individual testifies to the efforts that went into the creation of his obscure persona, not to mention the fictional characters populating the semantic forest of the NSRD, like that of Dr Eneser, Boiko’s alter ego.

While Surrealist and Dadaist artists often focused on the primordial and irrational, they were arguably also keen on observing and reflecting on the heavily mediated nature of industrial modernity, and thus fully appropriated the media of photography, film and print that defined their turbulent era. This is another aspect that allows us to draw a parallel between these historical precedents and the dream universe of the NSRD. The latter is also very media-conscious: it is filled with tape players, synthesisers, cameras, computers and other gear emblematic of its times, and can easily be called an uncredited precursor of the new media culture movement that was to develop in Latvia in the 1990s and 2000s with initiatives like the E-LAB centre for electronic arts and media, later revamped as RIXC. The aesthetic of the NSRD even has some echoes of the 1960s and 1970s Nove Tendencije exhibitions in Zagreb, although it eschews its geeky academicism.

For this reason, another similarly unruly and intermedial analogy from the same tumultuous decade of the 1980s comes to mind: Laibach and Neue Slowenische Kunst. Fittingly, in the summer of 2024, an exhibition entitled ‘Ausstellung! Laibach Kunst’ was on show at the Škuc Gallery in Ljubljana as a kind of homage or reincarnation of two one-evening exhibition-concerts held at the same venue in 1982 and 1983. The specific brand of provocative industrial-themed avant-garde, with ample borrowings from the spectacle aesthetic of totalitarian regimes, that Laibach actively exploited in their visual production can be recognised in the cold brutalist setting of the NSRD’s installation and performance that was part of the 1988 exhibition ‘Riga – Lettische Avantgarde’ in West Berlin. This unprecedented showcase of underground Latvian artists was brokered by the Latvian émigré Indulis Bilzens, a friend of Lediņš, and organised by Neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst, earlier headed by another legendary Latvian expatriate and one of the Fluxus pioneers, Valdis Āboliņš. A year before, in 1987, Bilzens had also contributed to the NSRD’s week-long performative First Exhibition of Approximate Art in Riga, by bringing in Maximilian Lenz, a pioneer West German DJ (or ‘record artist’, as he was dubbed at the time) who would later become known as Westbam.

Exhibition view, ‘NSRD: Information About A Transformed Situation’, Radvila Palace Museum of Art, Vilnius, 2024-25. Photo: Gintarė Grigėnaitė

These facts bring us back to the issue of the (non-)simultaneity of the cultural scenes in the late Soviet-era Baltic. In a sense, the various projects of Lediņš and Boiko appear to have been ahead of their time. What similar phenomena can be found in that period in Lithuania, where the exhibition devoted to the NSRD is now taking place? Most manifestations of intermedial, performative art forms came about here towards the late 1980s, with newly formed artist groups of varying visibility, such as Post Ars (Kaunas), Green Leaf (Vilnius, later reinvented as Jutempus, with a focus on new media and a different set of members), and Doooooris (Klaipėda), each trying in their own way to unhinge creative practice from the officially sanctioned and established forms of expression. Young composers, too, teamed up with visual artists, and organised several unofficial happening festivals in the town of Anykščiai, starting with ‘AN–88’.

But there was nothing quite like the NSRD. Lithuanian art groups were often focused on ecological issues as a metaphor for the repressive regime’s devastating impact on not only the natural landscape, but also on the very mental environment of the people it imprisoned, and these collectives’ performances and happenings often took place outside cities and galleries. This was also partly due to censorship, whose reach did not extend so far to the periphery, while official institutions were often off limits for their provocative and unconventional actions, deemed too transgressive even in the comparatively liberal context of perestroika and the nascent national rebirth. The message sent by the free and radical expression of live art was eloquent enough for the authorities to understand that it was directed against the decaying dogmas of the system.

The activities of the NSRD did feature some land art elements, and a focus on the countryside as well, but in general their aesthetic can be said to be boldly urban and hip, even metropolitan, with discotheques, stage performances and self-publishing that were perhaps more similar to what was happening in West Berlin rather than in Vilnius at the time. If we focus on the first half of the 1980s, no strata of unofficial Lithuanian art displayed this kind of creative freedom and synchronicity with developments further West. While the NSRD probably could not have achieved a level of artistic provocation like that of Laibach and NSK, the group’s projects still look surprisingly emancipated for the time, even if they were not widely visible in the mainstream.

There was also practically no group in Lithuania that would have consistently functioned as both a musical act and an art performance collective. As Lediņš was involved with the discourse of architecture, the prime Lithuanian counterpart could have been the new wave and art rock band Antis, whose original line-up consisted mainly of architects. But Antis was not actively involved in the artistic scene in the way the NSRD was. A later theatrical art rock band IVTKYGYG was fronted by Artūras Barysas-Baras, who was a maverick counter-cultural figure comparable to Lediņš, and had been one of the mainstays of the Lithuanian underground experimental filmmaker community since the early 1970s. However, the frame of reference for Baras would be hippie subculture and not new wave and electronic media culture. In addition, the artistic spectrum of the activities of IVTKYGYG, too, was not as wide and conceptual as that of the NSRD. One possible exception could be Žuwys, a band and later interdisciplinary art collective founded in 1996 in the city of Šiauliai, but it was much more obscure and local compared to the Latvian group.

Exhibition view, ‘NSRD: Information About A Transformed Situation’, Radvila Palace Museum of Art, Vilnius, 2024-25. Photo: Gintarė Grigėnaitė

It should also be mentioned that the political attitude of the NSRD is vaguer and more playful than the openly dissident stance of most Lithuanian groups of the late 1980s and early 1990s. It seems to have thrived in the ambiguities and loopholes of the late Soviet period, blending with a range of imported, imagined and transformed influences and references from Western art and the Western intellectual discourse (speaking of which, the scale of the NSRD’s awareness of concurrent developments and ideas beyond the Iron Curtain, as well as of theoretical prowess, is truly stunning and, I am afraid, unparalleled in Lithuania at the time). Hence the notion of ‘approximate art’ coined by Lediņš and Boiko: in a sense, it is a postmodern reading of the liminal state of the regime leading up to its ultimate agony. No wonder the NSRD effectively halted its activities after the Soviet era ended. But what the NSRD and the Lithuanian art groups had in common was an investment in creative collectivity as an antidote to the dehumanising collectivism imposed by the system.

What I found missing in the exhibition was a broader contextualisation of the NSRD with regard to the Lithuanian art scene. We only find out that the Latvians participated in a youth art festival in Kaunas, but it is unclear whether there were any further contacts with the Lithuanian artistic underground, or an awareness of its activities. However, this may not be the curators’ fault, but rather a reflection of the fact that although the Baltic States are very much aligned in their political orientation and values, there is still much to be learned about their respective art histories, and even contemporary processes that are going on as we speak. ‘Information about a Transformed Situation’ is a bold step towards actually changing this situation. And since it features tributes to the NSRD by some cutting-edge contemporary Latvian artists, it also begs the question which Lithuanian cultural icons from the 1980s would also merit such an inheritance.

Exhibition view, ‘NSRD: Information About A Transformed Situation’, Radvila Palace Museum of Art, Vilnius, 2024-25. Photo: Gintarė Grigėnaitė

Exhibition view, ‘NSRD: Information About A Transformed Situation’, Radvila Palace Museum of Art, Vilnius, 2024-25. Photo: Gintarė Grigėnaitė

Exhibition view, ‘NSRD: Information About A Transformed Situation’, Radvila Palace Museum of Art, Vilnius, 2024-25. Photo: Gintarė Grigėnaitė

Exhibition view, ‘NSRD: Information About A Transformed Situation’, Radvila Palace Museum of Art, Vilnius, 2024-25. Photo: Gintarė Grigėnaitė