Nothing is more far-fetched than reality. If a UFO were to descend before our eyes in the middle of the world’s largest city, or if someone with tangible evidence were to claim they were a time traveller, there is no way it would not be regarded as a marketing stunt or a deliberate hoax. We tend to be increasingly sceptical about life events. On the surface, multiple simulation theory themed books and movies were not supposed to make us seriously question the very fabric of our existence; but given how they have lulled us into feeling that everything has been orchestrated, scripted and staged, they might as well have been. And yet reality itself sometimes demands a certain degree of suspension of disbelief. ‘Stranger than fiction,’ we often say.

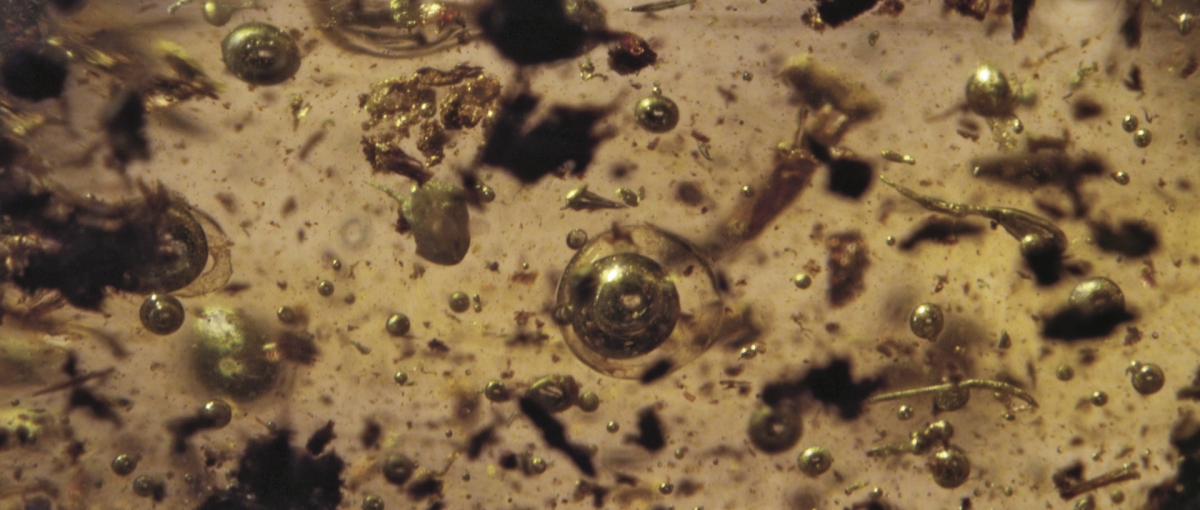

In his creative practice, the French artist Pierre Huyghe successfully transforms reality into something that seems fictional. This is especially evident in his single-work exhibition ‘De-Extinction’ at the Palanga Amber Museum (curated by Neringa Bumblienė). This video artwork, showing microscopic views of insects encased in amber at the exact moment when vitality and death intertwine, is mesmerising, and almost feels three-dimensional. The title of the piece relates to the ongoing scientific research into the de-extinction of prehistoric species, so not only does it speak about the past, but it also allows speculation about the future. Amber, so worn out by souvenir culture, folk crafts, and its role as the traditional ‘stone’ of Lithuania, reveals its other qualities: the ability to hold parallel worlds inside it, and to appear almost other-worldly.

Exhibition ‘De-Extinction’ by Pierre Huyghe at the Palanga Amber Museum, 2022. Photo: Gintarė Grigėnaitė

Pierre Huyghe investigates the possibility of a hypothetical mode of timekeeping. His objects are the earliest known specimens caught in mid-copulation 30 million years ago. We get to observe this hermetic universe without the inclusion of the rest of the world. This physical manifestation of collective (planetary) memory is an object incapable of deception. This contrasts with an older video piece by Huyghe, a two-channel projection on two juxtaposed screens, The Third Memory (1999), which examines the line between the memory of fact and the memory of fiction, and simultaneously questions their representations.

We almost always rely on personal experience when trying to understand art. Therefore, when a work of art requires the viewer not to rely on cultural references or emerging archetypal images in order to arrive at a better understanding of it, the goal seems to be to achieve transcendence. We are so used to concepts being reduced to symbols that images that create their own leverage appear to us as an active denial of experience of the world, almost like a visual deconstruction. And yet our minds still slip into old patterns of searching for narratives. In our daily lives we crush bugs without thinking, but Huyghe presents us with an abstract story with sympathetic characters, insects as the main protagonists of their own cosmogonic myth.

Metaphorically and quite literally, this video artwork is a sort of ‘exquisite corpse’ (in French cadavre exquis), a creative game that in this case is played collectively by both art and technology. It is not a completely new idea to present microscopic worlds as new and unimaginable landscapes, but Huyghe’s cinematic cross-section definitely achieves the illusion that we are travelling inside a cell or an atom, maybe another planet in a distant galaxy. The suspenseful soundtrack of the video artwork relays the whirring sounds of the camera, like an alien drone invading the peace and privacy of a frozen world that does not yet want to reveal all its secrets. As a rich palette of gold fills the screen, we can observe the perfectly preserved, now-extinct insects. Safe from decomposition and exposure, these ghostly apparitions can unconsciously awaken in us the envy of ‘survival’. We can’t know for sure that our attempts at leaving a mark in this world, be it building civilisation, exploration, or even creative endeavours, will stand the test of time. Fossilised tree resin capable of transporting small terrestrial invertebrates to the future may even surpass our time on this planet. Living organisms symbolically survive by taking the form of inanimate natural objects, thus challenging our notion of nature’s hierarchy and our place in it.

A still frame from ‘De-extinction’ by Pierre Huyghe, 2014, film, color, stereo sound, duration 12’38 min

A still frame from ‘De-extinction’ by Pierre Huyghe, 2014, film, color, stereo sound, duration 12’38 min

Sceptics would say that this piece could easily be recreated with other amber objects containing inclusions of insects, because the hard part of the work is done by powerful microscopic cameras; but that kind of argument has been used since the times of the first Dada artists, even though we understand that we no longer live in the era of the artist taking on the role of a skilled creator of original handmade objects. Instead, it would be useful to remember Duchamp’s words: ‘An ordinary object [could be] elevated to the dignity of a work of art by the mere choice of an artist.’ Accordingly, a video that maybe would not otherwise attract the attention of anyone but researchers, not because of its aesthetics but more because of its specific content, rightfully discovers its audience in the realm of video art. The artist shows us elements of reality that we simply would not be able to see with the naked eye, thus expanding our understanding of the world.

With regard to spectatorship, perception and imagination create the narrative which then acts as a tool for the transformation and deconstruction of the colliding cultural past and present. Huyghe’s video artwork gives its spectators an opportunity to ‘extend’ time by causing a contemplative state, similar to the sort of time that we experience when viewing large bodies of water, or the stars above. What is actually ‘extended’ is our sense of the present moment. As spectators, we are both extensions of a piece of art and witnesses to the reality it creates. Thriving in the ‘here and now’ through technological exploration, we make a new raw connection with the object in film. By transporting whole bodies of insects to the future, this amber stone itself becomes a record of nature, which is subsequently skilfully played by the artist.

Exhibition ‘De-Extinction’ by Pierre Huyghe at the Palanga Amber Museum, 2022. Photo: Gintarė Grigėnaitė

The exhibition ‘De-Extinction’ by Pierre Huyghe is on at the Palanga Amber Museum (Vytauto St 17) until 14 August.