The exhibition ‘Of Time and Mind’: Tõnu Tormis’ Portraits of Estonian Cultural Figures from 1964-2008, curated by Peeter Linnap, will be on view from October 18, 2024, to January 18, 2025, at Tartu University Library Gallery.

When choosing a background for the numerous portrait photographs of the Estonian photographer and musician TÕNU TORMIS (b. 1954), it is worth knowing that many Estonian photographers have made portraits of cultural figures their number one mission. As if anticipating the permanent and tragic possibility of the ethnic disappearance of our nation, Estonia has throughout the ages tried to systematically record and catalogue precisely those we call the ‘elite’, the cream of the brain-potential carriers that the uninterrupted history of the East and West has left us in spite of everything.

Jüri Palm, Mihkel Mutt, Hando Runnel, Olav Maran, Sven Grünberg, Peeter Mudist, Rein Kelpman… A short list, in no particular order, so as not to discriminate alphabetically or otherwise against those listed. In short: writers-artists-scientists-poets-educators.

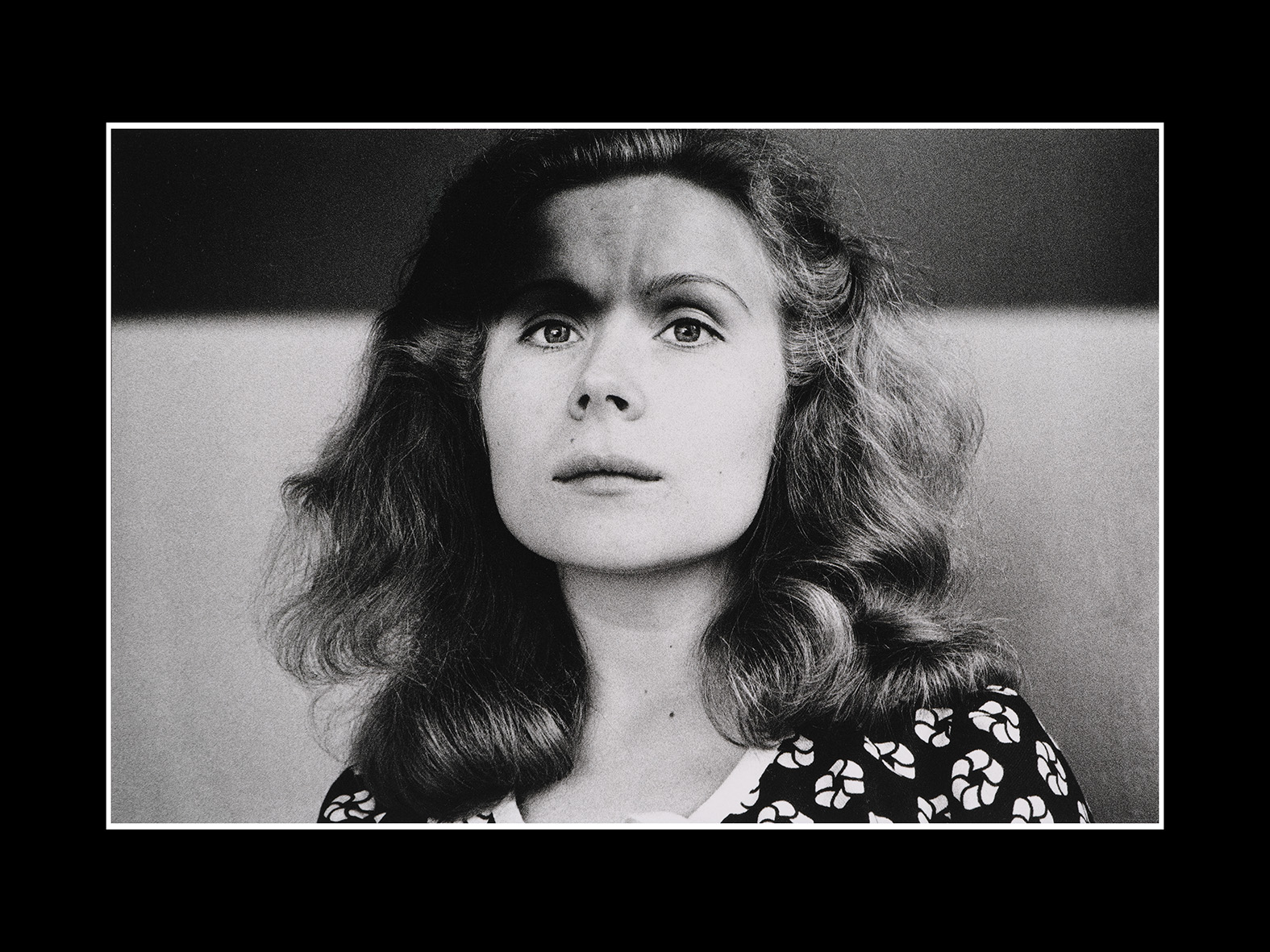

Tõnu Tormis. Doris Kareva, 1983

Their mode of representation is directly inspired by the architecture of Tõnu Tormis’s worldview, a static, even majestic, mode of composition. All of Tormis’s photographs were taken in the era of black-and-white analogue photo technology – they speak to us in a language of blacks, whites and greys, and his images are all about sharpness of image, laconicism and the interplay of light and dark.

A thorough knowledge of the sitter and a long-term observation of the subject are here decisive for his later pictorial characterisation. Tallinn’s craggy church steeples are probably as exclusive to the writer Mihkel Mutt as the three lions for caricaturist Heinz Valk, the pot palms around painter Peeter Mudist, the harbour-side shanty towns of naïve artist Rein Kelpman in the background, and the ethereal air curtains thrilling the senses of poetess Doris Kareva. Each Tormis’ icon draws on the aura of its subject with meticulous precision. Kelpman’s photograph, ‘made by Tormis’, conjures up Kelpman’s paintings from memory, as do Maran’s and Palm’s; showing Kareva ‘as she is’ naturally recreates the visual equivalents of her poetry, and so on. The series of portraits, like many of Tormis’s other photographs, leaves behind the age-old argument of ‘documentary’ versus ‘staged’ photography. The pictorial environment is of course dictated and/or controlled by Tormis, but without it we could not consider him an artist. Let’s settle, then, for the piquant assertion that ‘documentary’ is a certain sub-genre of staging/ which is inevitably informed by the conventions of cultural consciousness.