Ieva Epnere, Renunciation, 2014. Video still

… the experience itself has a satisfying emotional quality because it possesses internal integration and fulfillment reached through ordered and organized movement. This artistic structure may be immediately felt (John Dewey, Art as Experience). [1]

These days, the emotional experience (and adventure) offered by art is like a superfluous privilege that, it seems, among the trends of contemporary art, has already become an old-fashioned requirement. Yet it cannot be denied that the art consumer, and the artist him/herself, continues to secretly yearn for its presence. There are some examples that offer evidence of this, among them the creative work of the Latvian artist Ieva Epnere.

In her works, Ieva takes hold of the surrounding reality and unveils it, offering a distinctive sense of closeness to a particular place or personality. In her investigations of situations, contexts and people, she not only draws close to them but also transmits what she has seen as an emotional experience – a work of art, which is both aesthetically attractive as well as abstract and even magical. It’s hardly surprising that texts describing the artist’s creative work often emphasise that her approach is like an anthropologist’s. The artist has the ability of establishing a connection with the protagonists of her works and the objects of her examinations, and to be genuinely interested in their lives and characters. In her works, Ieva reveals a sense of closeness and intimacy. As the art historian Anita Vanaga pointed out in one of her reviews: ‘She knows how to win trust, doors are opened to her, she receives invitations.’[2] Contact established not only behind the frame, but also within the frame, was already evident a long time ago, in many of the works created in the early days of her career, when Ieva’s surname was still Jerohina. This was around the turn of the century, after she had recently graduated from ‘Grants’ school’.[3] Andrejs Grants has influenced many of Ieva’s peers; however, it is interesting to note that, with regard to Ieva, he guided her towards video art. An initial inspiration for her interest in this medium specifically were the works of Bill Viola.

Ieva Epnere, from the series Mikrorajons, 2007. Photographs, video installation

Ieva Epnere, from the series Mikrorajons, 2007. Photographs, video installation

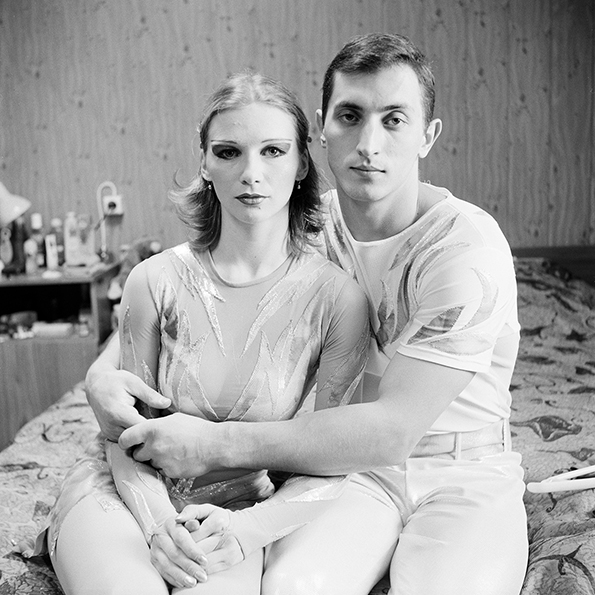

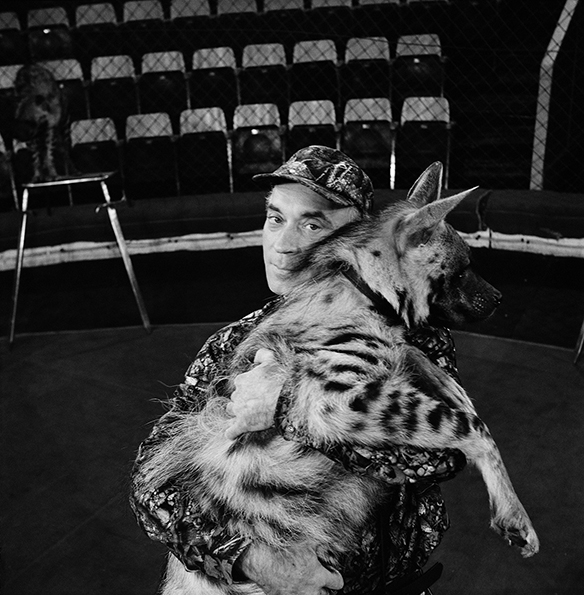

In the earliest stages of Ieva’s creative activities, while her personal style was still being developed, she made several series of portraits. For example, in the period from 2006 to 2007, while participating in various residencies, the artist documented young people in Riga, Reykjavik and Dusseldorf. After that, she created social documentary portraits in the series Mikrorajons (2007) – taking photographs of adolescents in the environment of run-down post-Soviet housing estates, with the peculiar melancholy that is typical of these places. The sensibility of the psychological portrait is present also in the series Notes of a Travelling Circus, which came into being between 2004 and 2008/2009, when Ieva took documentary pictures of circus artists. For a while, she even joined a travelling circus, so as to have the opportunity to gain an insight into their lifestyle. Ordinary people going about their working life gaze at us from the pictures – whether tired or slightly agitated, relaxed or bored, happy and somewhat sad. In her circus portraits, Ieva draws open the curtain, showing the human side of circus artists, their everyday life where the brilliant special effects and make-up are only the surface patina; yet this definitely does not mean that the circus in the photographs becomes trivial and loses its charm; in fact, quite the opposite – it becomes more familiar and comprehensible.

Ieva Epnere, Four Edges of Pyramiden, 2015. Video still

Ieva Epnere, Four Edges of Pyramiden, 2015. Video still

Ieva Epnere, Four Edges of Pyramiden, 2015. Video still

In recent years, Ieva has brought forth several vivid, memorable video works that lead the viewer on a psycho-emotional journey – collages saturated with places, objects, architecture, materials and landscapes. For instance, one such work is the narrative recently seen in a number of exhibitions about the ghost town Pyramiden – an abandoned coalmining village on Svalbard Island, a protectorate of Norway, which was formerly a part of the Soviet Union. Pyramiden was founded in 1910 by the Swedes, who in 1927 handed it over to the Soviet authorities. When in 1998 the coalmining operation was closed, the majority of the inhabitants and workers abandoned the place. Since then, Pyramiden has been largely uninhabited, but has now become an unusual tourist destination. In her work Four Edges of Pyramiden (2015), Ieva turns to the northern magic and beauty of the place, its silence and the attractiveness of its desolation, combining breathtaking scenes of natural landscapes with the stories of the people who are still living there. ‘My soul becomes more contemplative […] Pyramiden gives me good energy,’ says one of the rare local residents in the film about the place. In Ieva’s work, this unusual place in the northern back-of-beyond is not just one of the usual singular peripheries, but rather a symbolic point of reference for an internal journey. It is a place to fall in love with, and to lose yourself. This is also indicated by the protagonist of the film – a dark-haired woman in stylised Russian folk dress who can be seen at work only from behind, conscientiously moving away into the unknown, from one point to another. In this video, place or space becomes the chief protagonist, to be experienced not only emotionally and physically, but also symbolically, in the imagination (for example, the blue dream representing the ideal utopian city), because, as we know, the pyramid shape holds powerful, even curative energy.

The psycho-emotional nature of Ieva’s work could be characterised by a reference to the theoretician Giuliana Bruno’s idea of ‘e-motion’, in which the words motion and emotion are united. The meaning of e-motion is historically associated with ‘a moving out, migration, transference from one place to another’.[4] E-motion provides us with an experience that is related to space and spatiality (both real and unreal), where e-motion happens.[5] Bruno writes that our imagination is led through space by the camera, it is transported and carried away by emotion. As we go through it, it goes through us and our own inner geography. This allows us to look at the transference of emotions from character subject to object and back again in a reverberative process throughout the films.[6]

The stories and experiences depicted in the photographs and video works created by Ieva are enmeshed with the environment and nature, with the surrounding objects and mood. Even the surface and shading of woven fabric can become an important note in conjuring up atmosphere, as can be seen, for example, in the video work Extreme Fugue for One Voice. Laima (2013). At the beginning of the work, the singer Laima Lediņa is seen only from the back – a white, ornately embroidered collar, a milk-white blouse, a crimson red plait, a glimpse of a pearl earring behind the hair. One can become immersed in these beautiful details, until slowly she begins to sing, an extreme fugue composed by the young avant-garde composer Evija Skuķe – at the outset full of sighs, slow-moving, faintly cumbersome, gradually transforming into a sonorous, deep-toned cry. It is an exercise for one voice, along the so-called tortuous path of the vocalist towards a perfect rendition. Ieva states that she was interested in presenting the singer’s body as an instrument, the relationship between the human voice and the performance space. This video close-up or portrait is simultaneously intimate and abstracted. The task is not to reveal the personality of the singer in question, but rather the overall beauty that is expressed in this concentrated and intense recital.

Ieva Epnere, Renunciation, 2014. Video still

Ieva Epnere, Renunciation, 2014. Video still

A similar emotional experience is elicited when watching Renunciation (2014). The chief protagonist of the film is a young priest who works in the Catholic parish of Alsunga, a district inhabited by Suiti (a Catholic Latvian ethnic group with historic links with the Poles). There his life is involved not only with the local Catholic congregation, following a simple and abstemious lifestyle, but also devoted to art, for example, the conservation of priestly garments – historic chasubles, as well as introducing to the public the local tradition of Fauxbourdon singing. The work not only shows the unique traditions and beauty that can be found in the small area of the Suiti, but also describes poetically the passions of this young priest. Even though there is the word ‘renunciation’ in the title, what is being celebrated here is actually devotion to the love of beauty. The frames of the film often pause on nuances and details – materials, textures, surfaces, threads, cloths and the embroidery on them, as if lifted out from picture books. These moments attract particular attention, in this way creating stopping-off points for the journey offered by the camera. A love of materials, textiles especially, which is expressed not only in this video but in many of Ieva’s other works, is a reminder that the artist has a BA degree in textile art. The object with its structure and characteristic features is essential in Ieva’s works – like the people who weave their threads and the paths of their lives, and pursue their choices. The camera in Ieva’s hands is like an instrument for the restoration of the presence of sensations – smells and touch, for a sensory experience which is reawakened in our, the viewers’, memories.

Ieva Epnere, from the series Circus, 2003-2008. Photographs

Ieva Epnere, from the series Circus, 2003-2008. Photographs

Ieva Epnere, from the series Circus, 2003-2008. Photographs

Ieva Epnere is the winner of the kim? Residency Award 2016 in partnership with International Studio & Curatorial Program (ISCP) in New York.

[1] Dewey, J. Art as Experience, page lw.10.45 https://www.uio.no/studier/emner/uv/uv/UV9406/dewey-john-(1987).-art-as-experience.pdf

[2] Vanaga, A. Ievas Jerohinas Zilais putns // Fotokvartāls, No. 1(5), 2007, p. 24.

[3] Andrejs Grants (born 1955) is a well-known photographer in Latvia, famous for his ‘decisive moment’ photographs. Most of the younger generation of Latvian photographers have studied with him.

[4] Bruno, G. Atlas of Emotion: Journeys in Art, Architecture and Film, p.1., from the summary: https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/2314396/guliana-bruno

[5] Ibid, p.2.

[6] Ibid, p.9.