The duo exhibition Itsekuva presents recent work by two accomplished and uncompromising artists, the photographer Violeta Bubelytė (Lithuania, 1956, lives in Vilnius) and the painter Henry Wuorila-Stenberg (Finland, 1949, lives in Helsinki). It also launches a mini-series of two exhibitions, intended to bring artists from Finland and the three Baltic countries closer together in this time of war and crisis.

Itsekuva may be translated as ‘self-image’, itse being the word for both ‘self’ and ‘the Self’ in contemporary Finnish. It is an ancient word with correlates in several other Uralic languages. In Mansi, for instance, a severely endangered Ugric language spoken by some 900 people in Western Siberia and considered one of the closest relatives of Hungarian, is is reported to mean ‘a person’s shadow, the transparent and wandering spirit of a living or dead human’.

When we use Itsekuva as an exhibition title we hope it will reverberate with such lost (or almost lost) shamanic meaning: Itse as a particular part of the soul, a protective spirit that leads a person through life like an archaic doppelgänger and, interestingly, much like the pre-Christian Karelian Luonto, another guarding and guiding spirit whose name today signifies ‘nature’.

Itsekuva thus also reverberates with the titles of the solo exhibition Martti Aiha: Omakuva (‘Martti Aiha: Self-Portrait’) and the group exhibition Luontokuva (‘The Image of Nature’), both shown at Kohta in the autumn of 2018. Furthermore, in this extended meaning itse alludes to the phenomena of ‘soul loss’ and ‘soul retrieval’ that are central to both traditional and revived shamanic healing practice.

The two artists in Itsekuva are no strangers to the problematic of imaging the Self. Indeed they have spent decades elaborating dynamic approaches to it in the relative (but also very real) seclusion of their studios. They have been practising self-searching and self-mockery, carefully avoiding any identification of self-portraiture with self-obsession. The artist’s own body, they both assert, is simply the live model who is always at hand and needs no instruction.

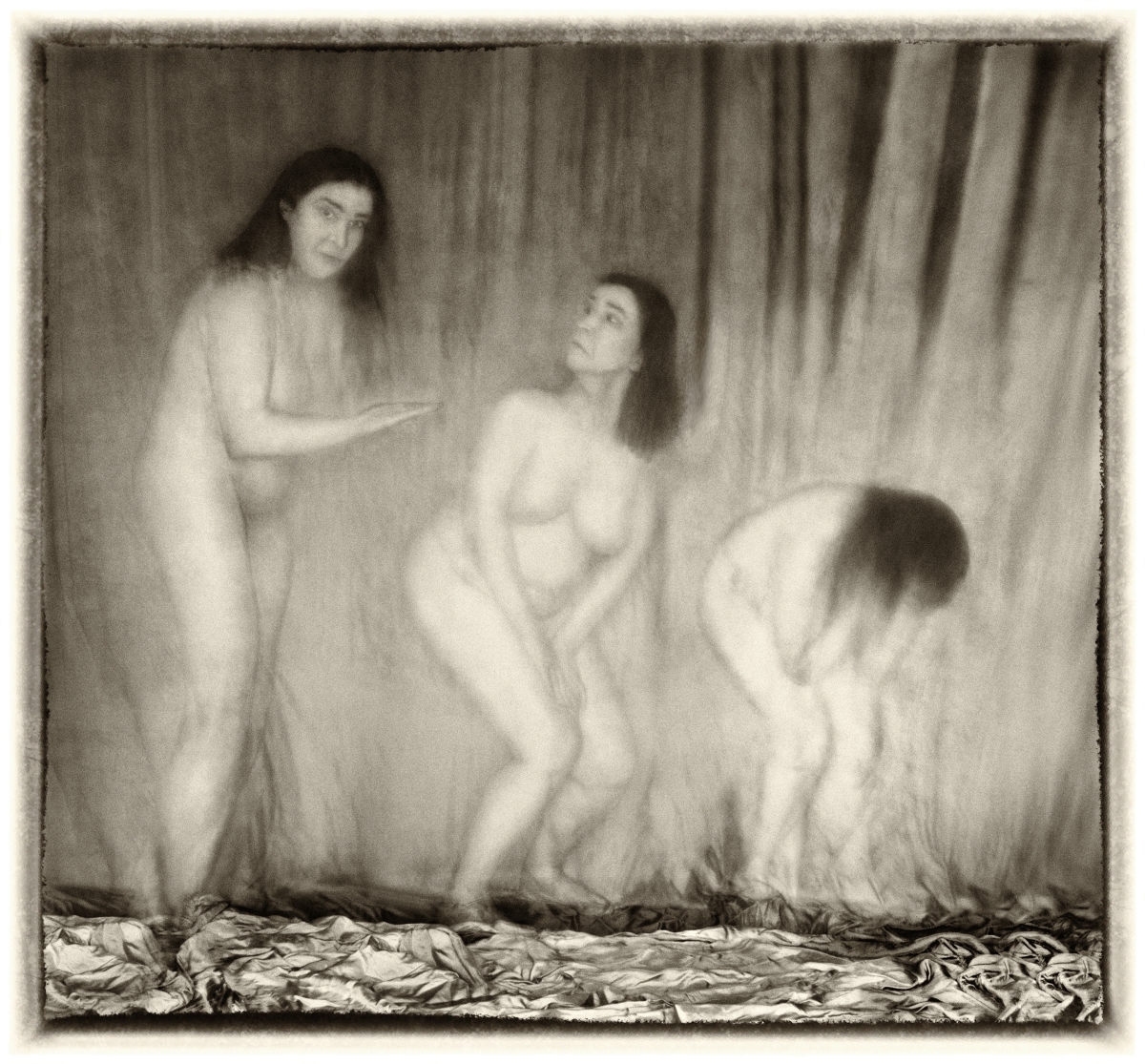

If the exhibition presents a spectrum of approaches to the self-image from the theological to the theatrical (with inspiration from sources as diverse as transcendental meditation and pantomime) then Violeta Bubelytė’s photographs from the last seven years clearly represent its ironically playful end. Nevertheless, some of the attitudes she strikes in them explicitly evoke religious art, as do titles like Expulsion, Expelled and Have Mercy with Us (all 2018).

In the early 1980s the self-taught Bubelytė began a long series of photographic performances, picturing herself in the studio, in the nude, gazing steadily into the camera. This first body of work, titled Act, spanned more than 15 years and has been compared to Francesca Woodman’s and Cindy Sherman’s photographs or Marina Abramović’s performances.

Kohta is showing a selection from a second body of work began in 2015, after she left her job as a newspaper photographer. This reinvented, re-engineered Bubelytė is more advanced: technically, visually and morally. Relying on deep-level digital editing, she seeks artistic freedom of the fullest kind under a regime of nudity that is now quite different – and not primarily because her body and face are no longer those of a woman in her twenties or thirties.

She – the author and the character – is burlesque rather than statuesque, but at the same time dignified in her disregard for decorum. Bubelytė’s newer work brings to mind the best Lithuanian folk art of the early twentieth century, fusing Gothic awkwardness with Baroque artfulness and the quest for a laconic ‘poor’ image that does only as much as it must.

Henry Wuorila-Stenberg studied painting abroad, in Italy, West Germany and East Germany. This was a rare choice for an aspiring artist in Finland at the time. It opened up tracks that many of his contemporaries tended to avoid, from the engaged (but conspicuously coloristic) figuration of the mid-1970s through the emotionally charged (but visually restrained) abstraction of the late 1980s to the exuberant fluid mindscapes, clearly inspired by Buddhist meditation and painting practices, of the mid-1990s and the messy fabulating auto-fiction of the 2000s and 2010s, when works on paper became an important part of his output and when his ever-open mind also embraced Greek Orthodox Christianity.

Yet Wuorila-Stenberg, who has a distinguished teaching career behind him, also inspires younger generations of Finnish painters to regard art as an arena for philosophical speculation, religious searching or spiritual development. These things are often assumed to be about self-expression, but he knows better than most that art depends on taking long detours through knowledge and skill.

He works fast, but what may seem like volatile mental states spontaneously committed to canvas are in fact outgrowths of his superior technique and sophisticated thought. Wuorila-Stenberg has spent the last three years in his studio in Helsinki, working ‘for the rack’, as it were, but sharing the results of his painting process on his Facebook account almost daily. Kohta is showing a selection of these paintings, most of them from 2021 and 2022, of faces and bodies that may or may not be his own.

He lends his new figures identities that are male or female, tactile or cerebral, painterly or graphical. The heads are severed and floating, or attached to necks that sometimes appear too long, or staring at us from austere dark backgrounds reminiscent of the Spanish Baroque. The bodies, when they occur, seem almost to make excuses for themselves, acting as if they were going to dig themselves in under complicated tangles of brushstrokes.

Finally there are the larger compositions (or perhaps de-compositions) that threaten to implode from irruptions of colour and paint but nevertheless leave space for a multitude of piercing eye-like shapes. In such maximalist newer work Wuorila-Stenberg appears open to the possibility that lost souls may be retrieved, or that demons may be rehabilitated and become something more akin to guiding or guarding spirits – at least in painting.

Itsekuva is organised in collaboration with Lithuania’s cultural attaché in Sweden, Finland and Denmark, with support from the Lithuanian Culture Institute.

Itsekuva

Violeta Bubelytė

Henry Wuorila-Stenberg

19 January – 2 April 2023

Kohta