I was recently invited to an exhibition where three generations of my relatives displayed their amateur artworks. Despite the earnest presentation, distinguishing between creativity and mere craft could have added depth to the exhibition. This experience sparked a conversation between me and my brother: Why do hobby artists gravitate predominantly towards painting, instead of delving into the arguably more captivating realms of installation or video art? One possibility is the allure of ‘polite aesthetics’, or catering to popular taste. Installation and video art often defy convention, challenge norms, and intentionally discomfit the viewer. Perhaps there’s a hesitation among many to expose themselves to scrutiny in this avant-garde context. After all, genuine creativity demands vulnerability, often revealing the artist’s core to the public.

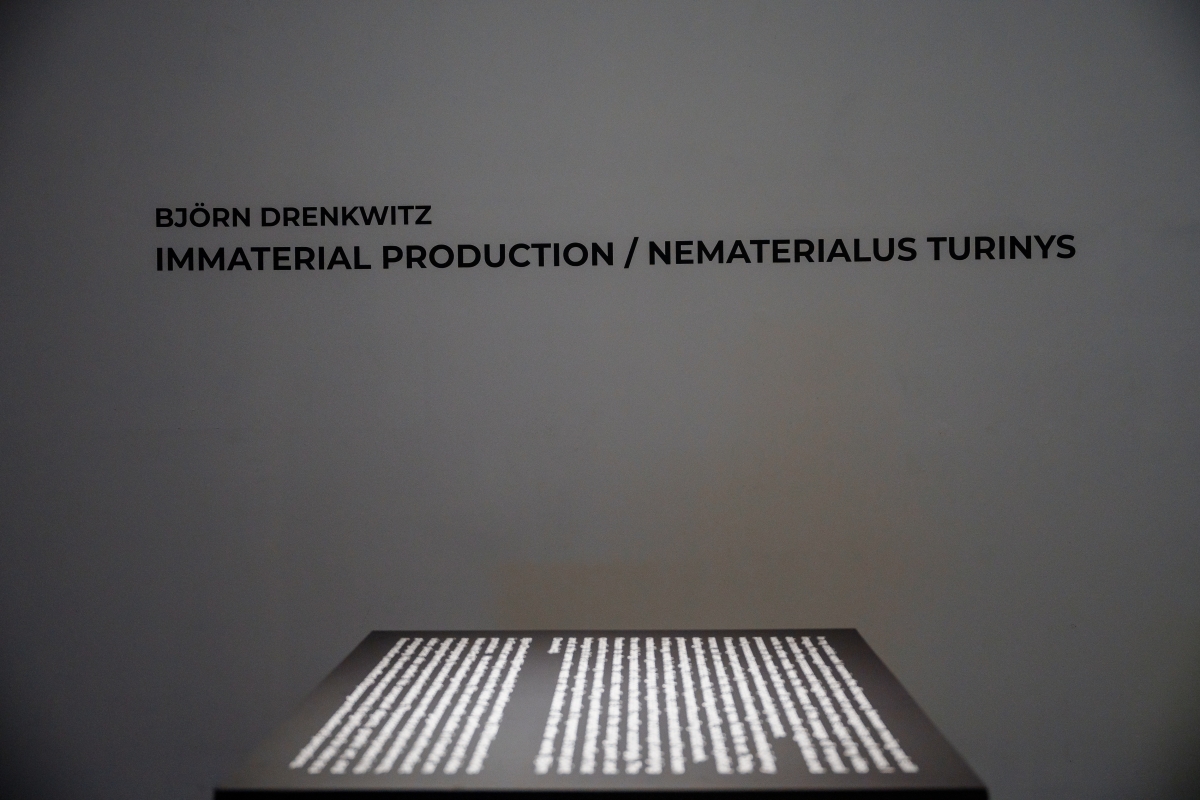

Speaking of video art, I recently came across the solo exhibition ‘Immaterial Production’ by the German artist Björn Drenkwitz. It is on display at the KCCC Exhibition Hall until 17 September. Video art is arguably one of the most immersive art forms. However, it often grapples with viewers’ short attention spans. In many exhibitions, there is a palpable irony: video art pieces, designed for immersion, are frequently skimmed over. Many attendees might put on headphones, but only devote a few brief minutes to the viewing. Is video art approaching the status of a written text, a classic form of communication that many now find too cumbersome to engage with fully? In an era where one can watch Citizen Kane on a telephone at double speed, investing seven minutes in Drenkwitz’s piece Light as Feather, where an actor simply holds a bird’s feather in his outstretched hand, demands an unexpected degree of willpower. I recall thinking, ‘I’ll try to replicate this at home with a stopwatch to try the experience.’ And so I did! But in the absence of a feather, I used a joke postcard featuring George Costanza. Talk about birds of a different feather!

Much of Björn Drenkwitz’s video art delves into the essence of time: its significance as a linear medium in video, and the profound impact of its passage on how audiences perceive it. In his piece 10 minutes, Drenkwitz films ten individuals, each attempting to gauge the passing of ten minutes using only their internal clocks. As viewers, there is an irresistible urge to assess who comes closest to the actual duration, or even contemplate the strategy one might employ to ‘win’ this temporal game. Personally, I would probably count the seconds in my mind, but the rhythm of my internal ticking may not align with real-world seconds. This subjective experience of time echoes the ideas of the philosopher Henri Bergson, who proposed that our innate sense of duration, or ‘lived time’ is distinct from its mathematical or spatial counterparts. Drawing a parallel in cinema, this reminds me of the matchstick dialogue by Max von Sydow’s character in the 1968 Swedish psychological horror film Hour of the Wolf directed by Ingmar Bergman: ‘A minute can seem like an eternity. It’s beginning now … ten seconds … Oh, those seconds … how long they last … the minute isn’t up yet … Now it has gone.’

Björn Drenkwitz interweaves philosophical references seamlessly into his work. In his piece Time and Being an actress sprints on a treadmill while reciting from Martin Heidegger’s renowned work of the same name. Likewise, in another piece that shares its title with the exhibition, an actor delivers a passage from Karl Marx, discussing the artist’s role in capitalist production, all the while doing a headstand. Such juxtapositions, melding physical feats with intellectual musings, provoke the viewer into considering the deeper intricacies and challenges of embodying philosophical thought in our contemporary world. They also pose the question, are many of our modern ideas merely remixes of past concepts, repackaged in ever more contortionist-like presentations? One might joke that there should also be a video where an actor, while citing Friedrich Nietzsche, balances on a tightrope over a pit of existential dread, and juggles flaming torches of truth, all while wearing a moustache that is just a bit too extravagant. And, of course, occasionally shouting ‘God is dead! But my balance isn’t!’

Sometimes, deconstruction can be remarkably literal. In the video piece Banquet, what starts as a meticulously arranged food display is abruptly disrupted by two cats ravaging the feast. While this may echo historical depictions of cats stealing food in still-life paintings, it has a more profound message. These cats, indifferent to the order before them, serve as a poignant reflection on today’s consumerism and economic climate. No matter how aesthetically refined something may be, it can be rendered inconsequential in the face of prevailing societal priorities and instincts. Take, for instance, the rapid obsolescence of beautifully crafted tech products. A sleek, state-of-the-art smartphone may be prized one year, only to be rejected the next year in favour of a newer model. This relentless cycle of consumption underscores the fleeting value we assign to even the most artfully designed items in our modern era. Or perhaps I should not delve so deeply; sometimes, cats’ high jinks are simply just that, cats’ high jinks.

The musician John Cage is credited with the assertion that ‘Art should be an affirmation of life, not an attempt to bring order …’ With this in mind, the video piece 100 Song Titles offers a compelling juxtaposition. In this piece, a professional opera singer improvises a monologue using the words of 100 song titles, each beginning with the word ‘Don’t’. Pop music, often seen as the quintessential art for the masses, is laid bare in this piece, revealing its inherent, if naive, didacticism. However, a counter-argument could be made: when stripped of their musical splendour, many operas might reveal themselves as convoluted tapestries of archaic, often misogynistic, tropes. While art and music across genres can indeed be critiqued, they invariably contribute to the rich tapestry of cultural expression, serving as reflections of the zeitgeist of their respective times. Often, delving into so-called ‘low brow’ culture, which caters primarily to blue-collar workers, can offer enlightening insights. These expressions, often dismissed or marginalised by the elite, express the raw emotions, aspirations, and lived experiences of everyday people.

The exhibition ‘Immaterial Production’, although perhaps not introducing a revolutionary new vision, and potentially seen as a retrospective of Björn Drenkwitz’s body of work (covering pieces from 2008 to 2016), showcases the artist’s gravitation towards classic aesthetics in his video structure. The artist himself professes to explore the aesthetics of the 1980s; however, given the pervasive ‘Eighties fatigue’ in contemporary culture, it may not always resonate with discerning audiences as wholly convincing. Nevertheless, Drenkwitz’s visuals are minimalistic and painterly in composition, often set against stark black or white backgrounds reminiscent of traditional painting. The meticulously arranged scenes, coupled with actors who follow closely the artist’s direction, evoke the style of famous artists like Bill Viola, Gary Hill and Candice Breitz. While some might label Drenkwitz’s style as somewhat ‘safe’ or even orthodox, I discern a distinct and invigorating nuance in his approach. There is a subdued elegance in his work that avoids flamboyance, offering instead an inclusive space for reflective engagement.

Exhibition ‘Immaterial Production’ by Björn Drenkwitz at the KCCC Exhibition Hall. Photo: Donatas Vaičiulis

Exhibition ‘Immaterial Production’ by Björn Drenkwitz at the KCCC Exhibition Hall. Photo: Donatas Vaičiulis

Exhibition ‘Immaterial Production’ by Björn Drenkwitz at the KCCC Exhibition Hall. Photo: Donatas Vaičiulis

Exhibition ‘Immaterial Production’ by Björn Drenkwitz at the KCCC Exhibition Hall. Photo: Donatas Vaičiulis

Exhibition ‘Immaterial Production’ by Björn Drenkwitz at the KCCC Exhibition Hall. Photo: Donatas Vaičiulis

Exhibition ‘Immaterial Production’ by Björn Drenkwitz at the KCCC Exhibition Hall. Photo: Donatas Vaičiulis

Exhibition ‘Immaterial Production’ by Björn Drenkwitz at the KCCC Exhibition Hall. Photo: Donatas Vaičiulis

Exhibition ‘Immaterial Production’ by Björn Drenkwitz at the KCCC Exhibition Hall. Photo: Donatas Vaičiulis

Exhibition ‘Immaterial Production’ by Björn Drenkwitz at the KCCC Exhibition Hall. Photo: Donatas Vaičiulis

Exhibition ‘Immaterial Production’ by Björn Drenkwitz at the KCCC Exhibition Hall. Photo: Donatas Vaičiulis

Exhibition ‘Immaterial Production’ by Björn Drenkwitz at the KCCC Exhibition Hall. Photo: Donatas Vaičiulis

Exhibition ‘Immaterial Production’ by Björn Drenkwitz at the KCCC Exhibition Hall. Photo: Donatas Vaičiulis

Exhibition ‘Immaterial Production’ by Björn Drenkwitz at the KCCC Exhibition Hall. Photo: Donatas Vaičiulis

Exhibition ‘Immaterial Production’ by Björn Drenkwitz at the KCCC Exhibition Hall. Photo: Donatas Vaičiulis

Exhibition ‘Immaterial Production’ by Björn Drenkwitz at the KCCC Exhibition Hall. Photo: Donatas Vaičiulis