Maarin Ektermann: At least two periods can be differentiated in your artistic work: first, working for quite a long time with political subjects applying a conceptual and feminist take on photography and film, and then in recent years turning towards digging the layers of visual culture, critically appropriating images from pop culture and the commercial sphere, images that create strong (visual) desires, but also forbid their realisation. The book that came out in 2022, a wonderful monograph, summarises the recent period. How did this turn in your artistic practice take place, and what were the most important moments that encouraged you to move forward in this direction?

Marge Monko: In around 2013, I felt I was somewhat stuck in my practice. The subject matter in my work also dictated the way of working, which was very much based on subject matter; there was too little space left for intuition. I wanted to work differently, but it took some time to work out how. During that period, I was accepted for HISK, a two-year post-diploma programme in Belgium, and that was a good opportunity to engage in some trial and error. I’ve been always interested in visual culture, especially advertising, and I started ordering some magazine ads from eBay. There is no doubt that I was also influenced by the context of Belgian contemporary art, which is largely apolitical but also very playful. This led to a body of work where I’ve been appropriating advertising photographs, for which I came up with a kind of subtitle, display and desire. So this book includes work from that period.

Erika Hock. Part one. Hosting – Marge Monko at Cosar, Düsseldorf, 2021. On the left and right: Erika Hock, Curtains (Female Fame). In the background: Marge Monko, Untitled Photogram #1. Photo: Cosar

ME: What was most difficult while making the monograph Flawless, Seamless? What was left out, and why?

MM: I think the most heated conversations with the editor Laura Toots and the designer Indrek Sirkel were about which works should be included and which should not. There are works that I thought were not strong enough, for reasons known only to myself, but I was in a situation where I had to explain it to my collaborators. For some works, I was not happy with the documentation, that is, exhibition views, so some hard decisions also had to be taken in this regard.

ME: There are also fewer essays in the book from the usual suspects, like art scholars and curators, and more of your conversations with friends and colleagues. In your conversation with Paul Kuimet in the book, you also talk about creating a discourse for yourself as a way of compensating for the shortcomings of art world agents like critics and curators. The editor Laura Toots and the designer Indrek Sirkel are also old friends of yours: why was it important to you to do this project together with people so close to you?

MM: Indeed, Indrek and Laura are my friends, but they are also excellent at what they do. So when Indrek suggested I start thinking about getting a new book published, I knew I wanted to work with him as a designer. Laura had recently done the editing of Paul Kuimet’s monograph, and she was immediately on board. I think the advantage in working with people you know well is that you can be direct and critical with each other without causing offence.

The book includes an essay by the German writer and curator Moritz Scheper, and conversations with my close colleagues Erika Hock, Maruša Sagadin and Paul Kuimet. Moritz had previously written about my exhibition in the Folkwang Museum, and I really admire the way he combines a psychoanalytical approach with a political approach in his texts. I always enjoy reading interviews and conversations with artists, so I decided to use this format for the book. I had recently had exhibitions together with Erika and Maruša. Both their practices are quite different to mine, but I think they’re great artists, and I’ve learned a lot from them. The initial idea was to have another essay by an Estonian writer, but the writer I had in mind was busy, and sadly there are not so many other local writers who have shown an interest in my work. So we decided to include a third conversation with a fellow artist in the local context. Paul was the obvious choice, because we talk about each other’s work, and art in general, on a regular basis.

Photo: Joosep Kivimäe

ME: In the book, you talk with Erica Hock about how she installed one of your video works in the joint exhibition herself, since you were not able to travel. How open are you to this situation, someone else installing your work, and you losing final control over it? Would you be interested in working in an even more collective way?

MM: It really depends on the work. In general, I don’t mind other people installing and ‘staging’ my work, but there are certain technical standards that have to be observed, and my experience is that these may vary, even if we talk about exhibiting in very respectable institutions. But in the case of Erika’s three-part show We Never Grow Tired of Each Other at the Cosar gallery in Düsseldorf to which I was invited as a guest artist, I had complete trust in her. She has high standards, and has acted as an artist-scenographer in a number of exhibition projects.

ME: Your projects are often based on deep research, a process that is often also left visible in the artworks themselves. Is it possible to do too much research, and thus spoil something for yourself, feeling that everything has already been said and done? Do you sometimes have the feeling that after having researched a topic for a while, an artwork or exhibition is not the most suitable vessel? And what would be?

MM: Yeah, things like that can happen. In my experience, it’s not because of doing too much research, but for some other reason: you might come to the realisation that you don’t have much to say about the subject; or you have sat on an idea for too long, other exciting topics have taken over, and so it just kind of expires. But in terms of research, I’m a bit of a nerd. When I’m fascinated by something, there can never been enough of it, and I sometimes feel that I could’ve dug deeper, but there comes a point when you have to put out a work.

Erika Hock. Part one. Hosting – Marge Monko at Cosar, Düsseldorf, 2021. Marge Monko, Sheer Indulgence. Photo: Cosar

ME: What attracts you to film? What can be expressed in this medium? There is no proper support structure for artist films in Estonia, so some of its practitioners also have to struggle quite a lot to realise their ideas.

MM: I guess my way of thinking has always been more linear and narrative than conceptual. And since my background is in photography, I’ve got the necessary tools for working with the moving image. I don’t think there are aspects you can only express in a moving image, but it’s a language which resonates with me. It’s true that it is very difficult to produce an artist film in Estonia, because until recently the Estonian Film Institute didn’t even recognise any such a category as experimental film, and there also haven’t been producers interested in it. But artists are resilient, and it seems that things are changing slowly. Together with my fellow artists Liina Siib, Paul Kuimet and Taavi Talve, I have created a production company with the name News from Nowhere Films, which will hopefully help us pursue our interest in filmmaking.

Marge Monko and Maruša Sagadin, The A.B.C.D.E.F.G. of Love, 2022, Hobusepea gallery, Tallinn, 2022. Photo: Marge Monko

Marge Monko and Maruša Sagadin, The A.B.C.D.E.F.G. of Love at Hobusepea Gallery, Tallinn, 2022. In the background: Marge Monko, Lucy In The Sky (The More I Make Love The More I Want To Make Revolution). In the middle: Maruša Sagadin, Untitled, 2021 and Bad Mood Without a Kiosk and Kitchen (Juliana with Capitals). Photo: Marge Monko

ME: How about ‘writer’s block’? How do you deal with getting stuck? How does your studio space function for you at difficult times? Is it a safe oasis from the world’s troubles, or do you prefer not to go there when times are difficult?

MM: I don’t have a specific method of dealing with a creative block. Sometimes it helps to keep your eyes open: going to the theatre and movies, listening to music, reading. Even when some of these things are not exactly your cup of tea, there might be a spark, and suddenly you know how to continue your work. Sometimes you just have to sit down and start working, it’s as ‘simple’ as that.

In terms of working in the studio, then yes, when Russia invaded Ukraine in February, it was impossible to focus on working there. Like many others, I felt it was more important to help as much as I could, and so I did. I have resumed my working rhythm now, but I’m constantly haunted by the thought that I should be doing more to help the Ukrainians.

Marge Monko and Maruša Sagadin, The A.B.C.D.E.F.G. of Love, 2022, Hobusepea gallery, Tallinn, 2022. Photo: Marge Monko

ME: Since the format of a monograph is about looking back, one cannot help but ask, what next? What topics excite you right now? What would you like to dive into?

MM: It seems I’ve reached another turning point in my practice again, but I can’t be any more specific, because rethinking one’s practice takes time. I’m still very interested in issues relating to the politics of reproduction, where there have been many setbacks worldwide, that is, thinking about Poland and the USA. The war in Ukraine has radicalised my East European identity (I have a mixed background of Estonian, Jewish and Ukrainian ancestry), and made me wonder what the elements in society are that enable and maintain these hyper-macho structures that we are witnessing in Russia today. With this in mind, I’ve been looking for alternatives in human history, and in this regard, the studies by the Lithuanian archaeologist Marija Gimbutas about Neolithic societies have been fascinating to read. Her conclusion is that the variety of female figurines and other finds from that period suggest that a feminine force played a wider religious role in those times.

However, at the moment I only have a vague idea of what form this line of thinking will finally take, so let’s leave it at that.

ME: At the end of the book, you and Maruša Sagadin exchange reading recommendations: do you have one to share with us as well?

MM: I recently finished the memoir Consent by Vanessa Springora, a first-hand account about a sexual relationship between an underage girl and a much older man, about how relationships like that have been tolerated and even facilitated for a long time, especially in the French cultural sphere, as part of practising artistic freedom. It’s tough reading, but I think it’s important that books like that are being written.

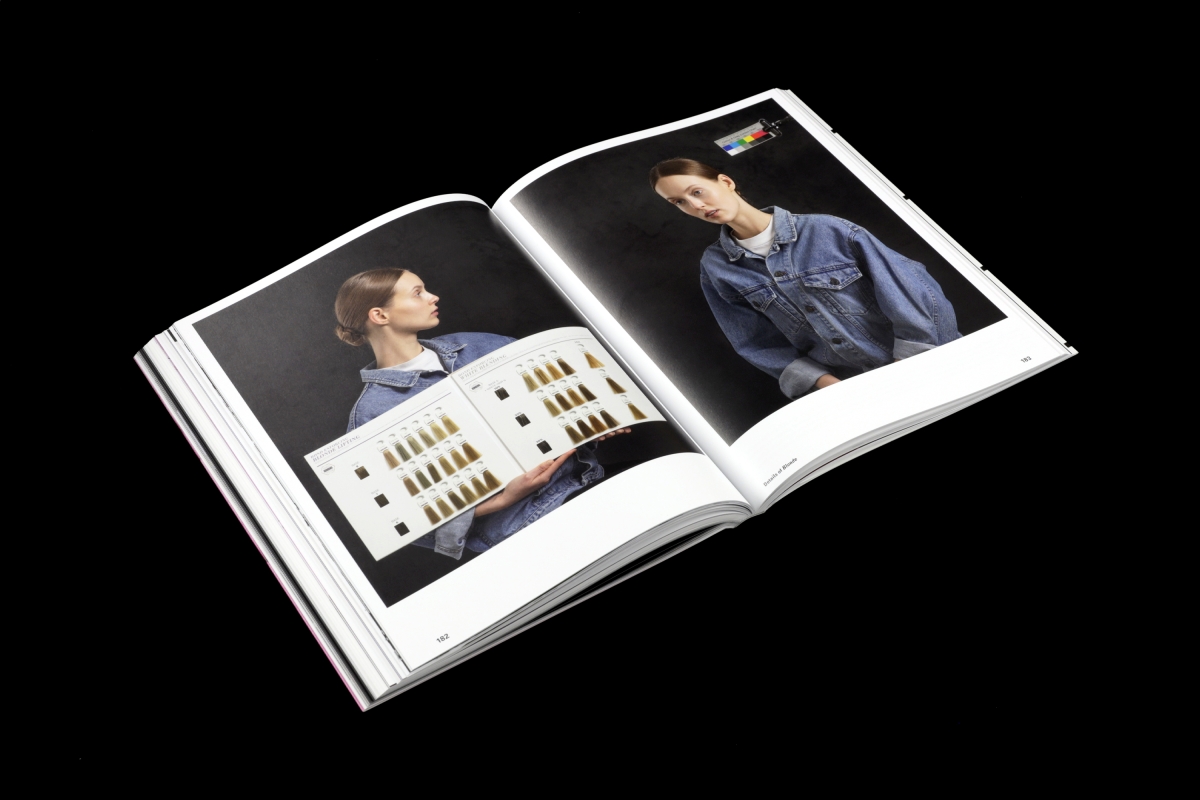

Photography: Joosep Kivimäe

Photo: Joosep Kivimäe

Photography: Joosep Kivimäe

Flawless, Seamless by Marge Monko

Edited by Laura Toots

With articles by Moritz Scheper, Erika Hock, Maruša Sagadin, Paul Kuimet and Marge Monko

205 × 270 mm

272 pp

Offset printing

Sewn binding

In English

Graphic design: Indrek Sirkel

Colour correction: Marje Eelma (Tuumik)

Typefaces: Various

Paper: Galerie Art Matt 130g, Galerie Art Gloss 150g, Galerie Art Silk 150g, Munken Polar Rough 120g, Amber Graphic 60g, Nautilus Classic 120g

Printed by Tallinn Book Printers

Supported by the Cultural Endowment of Estonia, FOKU—Estonian Union of Photography Artists

Edition of 400

Published by Lugemik

ISBN 978-9949-7381-9-9

2022

This conversation was held in Estonian at the launch of Flawless, Seamless at the Kai Art Centre, 23 September 2022.