“We are used to thinking about past times through the lens of national histories, with their selective, smoothed and linear narrations, instead of the plural, messy and nonlinear stories shared in daily life.” With this statement, the three curators Ieva Astahovska, Margaret Tali, and Eglė Mikalajūnė opened the introductory text for their joint exhibition Difficult Pasts. Connected Worlds at the National Gallery of Art in Vilnius. The exhibition had already been shown in a slightly different form at the Latvian National Museum of Art in Riga in 2020 as part of the large-scale, interdisciplinary project Communicating Difficult Pasts organized by Astahovska and Tali, but it was not on view for long due to the pandemic.

Difficult Pasts. Connected Worlds focused on the intertwining of different national histories. The curators fanned out a kaleidoscope of histories that merge and intertwine, appearing in ever-new guises through a web of references and, in some cases, coming back to the surface of perception for the first time. Thus, right from the entrance hall, the past of the building literally cast long shadows up to the present thanks to Paulina Pukytė’s work Shadows (2022). With black sand, the Lithuanian artist marked the imaginary shadows of the individual columns of the entrance area on the floor. The sand shadows, however, pointed in different directions and thus indicated different sun positions and the restless passing of time. Visitors’ shoes carried the sand into the rest of the exhibition space, weaving together the different stories told there. The modernist building was designed and built in the 1970s for the Museum of the Revolution, opening in 1980 and closing in 1991 after the end of the Soviet era. It was not until 2002 that the Lithuanian government decided to rebuild it for the establishment of the National Gallery, which began to operate in 2009.

Not only did the sand make its way throughout the history-rich exhibition building, but the exhibition itself wound its way across the various floors, some of it embedded in the permanent collection, like Laima Kreivytė’s artwork Mortification: In Search of the Black Book (2022). Kreivytė’s work focuses on the controversial biography of Lithuanian national poet Salomėja Nėris, who fought for Lithuania’s incorporation into the Soviet Union and praised Stalin in a poem. Her tragic death after World War II left many questioning whether she was really an ardent Stalinist or had been forced. The artist set out to explore the poet’s identity as rendered in various representations of her. A video in which Nėris’s face rotates like a mask is surrounded by various paintings and sculptures of her, on which and in which she is represented differently and thus her life is always interpreted differently. This installation is located in a room devoted to the gallery’s Lithuanian art collection and illustrates not only the interweaving of the different layers of time, but also the changing interpretations that individual events can experience in the course of history, thus drawing attention to the constant and repeated rewriting of these. The never-ending process of writing history itself becomes vivid, which begins anew with each generation that writes its own history.

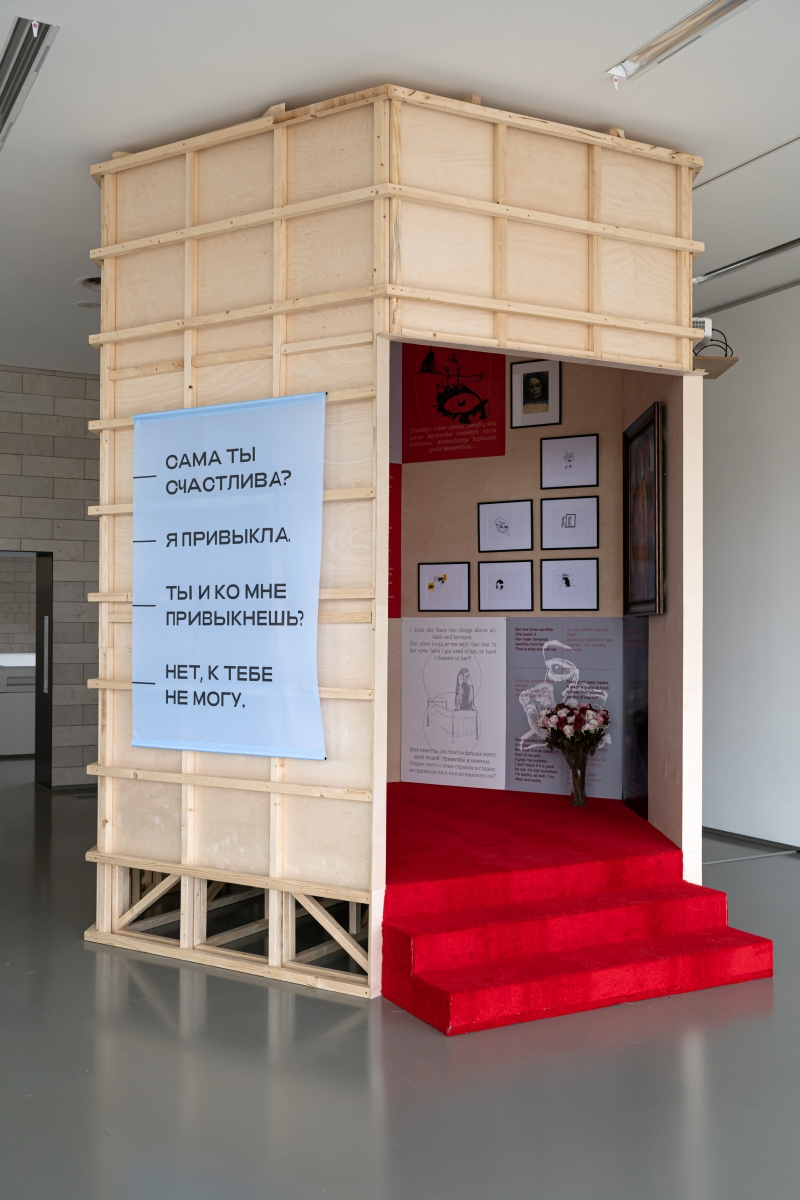

Along the winding path through the National Gallery, works in the exhibition repeatedly entered into meaningful relationships with the history of the building, revealing further temporal layers and the struts of each narrative. For example, both Zuzanna Hertzberg’s 2017 work Nomadic Memory and Eléonore de Montesquiou’s artwork 33 Monsters (2022) were placed in or near locations where propaganda flags from the collection of the former Revolutionary Museum used to hang. In both cases, the voids of history are addressed, reflected in the isolated traces—the flags—of the building’s past, which is otherwise no longer visible or tangible. In this way, they reference the Baltic states’ difficulties in coming to terms with their former affiliation with the Soviet Union, which was painfully perceived as colonization and should therefore be forever erased from collective memory.

Hertzberg recalls the combatants of the XIII Dąbrowski Brigade, erased from the cultural memory in the course of the process of decommunization in Poland. These combatants were not only communist but also Jewish and ethnic and national minorities belonging to a wider left spectrum, who fought for democracy as part of the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War against the fascist Franco regime. A replica of a marble slab honoring the Dąbrowski Brigade, displayed in a glass case, was placed in a 2017 intervention on the site that formerly documented the building where the Polish Communist Party was founded.

In her work, de Montesquiou creates a tribute to her ancestor Lydia Zinovieva-Annibal’s 1907 novel 33 Monsters. That text celebrates lesbian love and therefore made the author an unloved member of her family as her identity deviated from the heterosexual norm. Lydia’s self-chosen surname, Annibal, is a reference to her forgotten ancestor Abraham Petrovich Hannibal, a Person of Color kidnapped as a child who later worked for Peter the Great at court.

Other gaps in the historiography, which ominously affect the present, were brought to our attention in the works of Vika Eksta and Lia Dostlieva and Andrii Dostliev. In the 20-minute video that was part of Eksta’s multimedia installation Conversations with Dad (2020), the artist attempts to engage her father in conversation about his deployment in the Soviet-Afghan War, which only succeeds when he has been drinking. However, the trauma of these war events and their stressful effects on the soldiers and their families were never brought up or acknowledged in Soviet society. The soldiers were left alone with their post-traumatic stress disorders, which not infrequently resulted in alcoholism, as in the case of the artist’s father.

The artist couple Dostliev trace the consequences of the Holodomor in their own lives. The great famine in Ukraine in 1932 and 1933 cost the lives of up to 7.5 million people, yet has not really found its way into Soviet historiography to this day. In I still feel sorry when I throw away food… Grandma used to tell me stories about Holodomor (2018), the pair document the leftovers of their daily meals, uneaten and thrown away, which is linked to a sorrowful yet unfounded sense of guilt. The trauma of hunger is passed on to the next generations. The work shows how past events are imprinted on people’s bodies over decades, shaping them and inscribing the past onto the future.

A second work by Paulina Pukytė, titled Ghosts (2022) – the various crystal vases and bowls scattered around the building in inconspicuous places not only commemorate the Soviet era—when they represented middle-class affluence, although they can now be purchased at flea markets for little money—they also appeal to visitors’ personal childhood memories—in this case, especially those of the author herself. Her own narrative of the crystal bowls—which her mother could never have afforded, but which were given to her out of gratitude by the parents of the children in her school class, and were then given a representative place in the closet, although they then only served to store loose notes and slowly gathered dust—connects with the grand narrative that is invoked here.

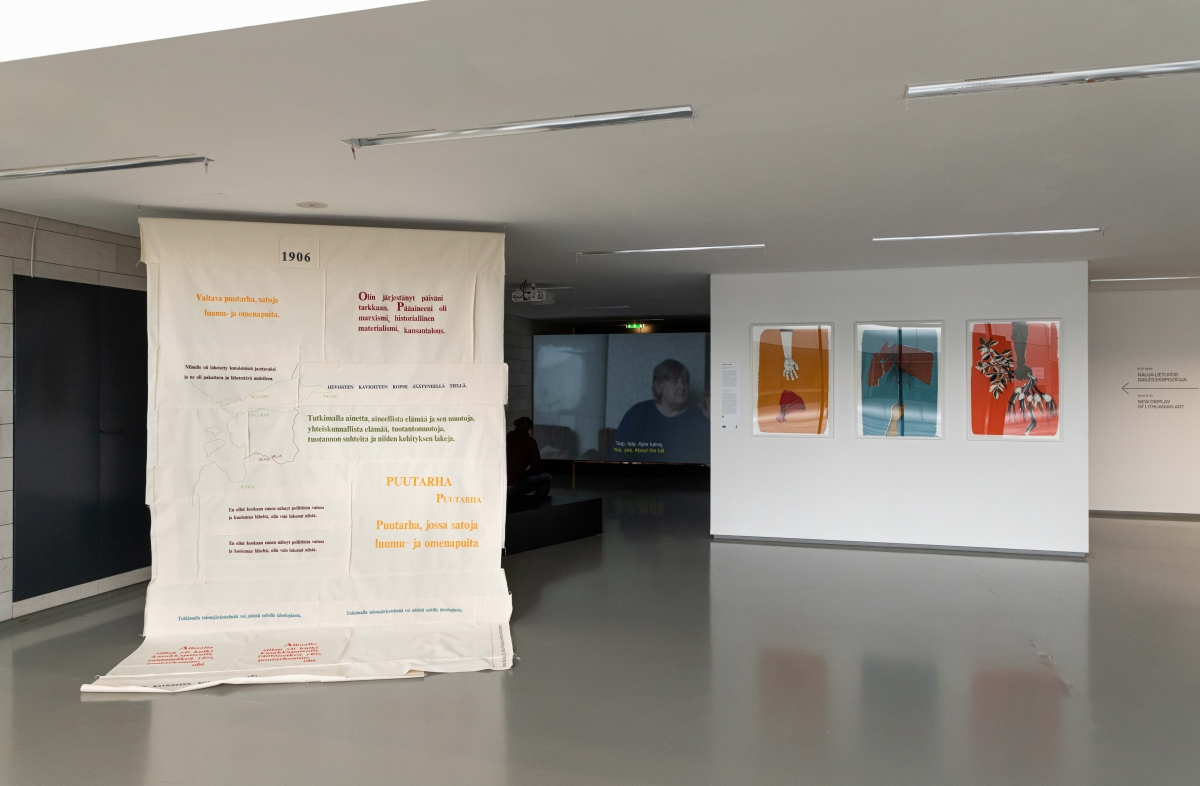

The complexity of history and the concatenation of different strands of history, which in this exhibition demonstrated that it is always a plurality of different narratives and rewritings, which are always in the process of becoming and are not finished even in the present, seemed to culminate in the multimedia installation We Offered Maurice Dates, Grasshoppers and Water Pt. 2 (2020–2022) by Quinsy Gario and Mina Ouaouirst. This work intertwines Saint Mauritius’s journey from Sudan to Switzerland with Lithuanian and Latvian history, as well as Dutch colonial history in the Caribbean. Saint Mauritius was featured on the coat of arms of Vytautas the Great, who was both the Grand Duke of Lithuania and the patron saint of the Brotherhood of Blackheads in Riga during the transition from the fourteenth to the fifteenth century. The chant in the Berber language, Tamazight, that came from the loudspeakers poetically speculates on the saint’s path and the possible stop he might have made in a Berber village. The carpet woven by artisans in Taznakht, which was part of the installation, features both the saint’s route and a map of Tobago. This work points beyond the interweaving of individual national histories through the figure of Saint Mauritius to the ways in which history is transmitted both orally and in the form of artifacts.

With this exhibition, the curators tested a new understanding of history, one that they described as “a radical displacement for our frames of reference, a radical transvaluation of our methods and of our philosophies of history,” in Walter Benjamin’s sense, where history is a mosaic or collage, as constructed from the present, which does not simply proceed chronologically and linearly and allows for a thinking together of antagonisms. This understanding of history also allows us to think of a flare-up of a forgotten past in the present that structures and shapes it; to think of the present, as it were, as a resonating body of the past. This is an approach that proves to be particularly important and meaningful in these times of resurgent nationalist tendencies—not only in the countries of the former Eastern bloc—allowing us to counteract identitarian and exclusive images of history.

Exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in Vilnius from 29 April to 28 August 2022.

Photography: Gintarė Grigėnaitė