The exhibition Do Come in, the Door is Open! at the Kumu Art Museum puts together works by three female artists, Edith Karlson, Mary Reid Kelley and Eva Mustonen. According to Triin Tulgiste, the curator of the exhibition, these seemingly disparate art practices can ‘in the broadest terms, be characterised as narrative art that uses fiction as a method. Karlson, Kelley and Mustonen are essentially storytellers who use both words and visual images, often combining the two, to tell their stories.’[1] The title of the exhibition is a happy quote from the Estonian television series Õnne 13 (literally ’13 Happiness Street’). It serves as an invitation ‘to enter a distorted-mirror environment, which is rooted in things mundane or personal, and aims to take a more general stand on contemporary neuroses and tensions’.[2] Once you open the door, there is no way back, at least not before you have found your way through endless labyrinthine traps.

The exhibition is built around four key words: monster, body, home and explosion, which eventually become intertwined and overlapping, described by the artists through rather intimate and personal stories. Entering the exhibition and wandering through the spaces feels almost like encountering a fairy-tale drama. Scenes recalling the film Fanny and Alexander,[3] where an over-imaginative child faces the many joys and dramas of family life, while growing up and hiding his fears and anguish behind lavish theatrical props.

Eva Mustonen’s detailed sculptural pieces reveal layer after layer of a rewarding fantasy world that often consists of everyday (cookery) items and materials, sometimes as simple as coffee (My Head is Strong, 2019), or an old piece of furniture (If I’m Missing Someone, Would it Look Like that?, 2013–2014). Used kitchen utensils and old textiles from the Soviet period bring out rather nostalgic memories, leading the viewer through certain moments and places in the artist’s past. The airy and sweet consistency of a pink zefir, as part of the installation My Head is Strong (2019), can take you back to childhood gatherings or a grandmother’s teas, while it can also give the nauseous feeling of an overdose of sugar. Using food as sculptural material provides the possibility to serve it as a protective prop from the outside world, to keep control of memories that, either in a good way or a bad way, can haunt you.

By deconstructing mundane objects, Mustonen acts as a bricoleur, playing around with meanings that have been given to familiar everyday items. Her intimate and welcoming houses Eva’s Garden (2019), built to ignore conventional grown-up rules of how things should be named and done, offer shelter and protection, and invite us to step in. Meanwhile, the flames (Edith Karlson The End, 2019) surrounding the wooden houses recall the continuous fight over what belongs to the artist and what belongs to the outside world. For Mustonen, home seems to be both a secure comfortable space and a theatrical stage, for everyday rituals that might help to heal anxiety and worry.

Eva Mustonen. Eva’s Garden. 2019. Installation. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Hedi Jaansoo

Edith Karlson’s sculptures are straightforward, not hiding the anguish and fear behind a mask of perfection. Cast either in raw concrete, subtle porcelain or smooth silicone, the monsters created by Karlson are not for the faint-hearted. The installation Sisters (2019), enormous serpent-like creatures crawling around the exhibition space, brings out the beliefs and (mis)interpretations surrounding these earthly beings. Usually referred to as harmful and evil, a symbol of seduction and havoc, here serpents become a supporting and uniting force, gathered together in a headstrong group.

Karlson’s nightmarish tales are often crafted with ambivalence, giving the grotesque side of life-empowering strength. Her installations Doomsday (2017) and Four Letter World (2018) provide evidence of physical and psychological changes in the female body during pregnancy and after giving birth. Motherhood is shown through a prism of distorted body parts, which become a testimony to bodily changes in time. In rather an uncomfortable way, Doomsday sculptures bring into focus the constantly changing (female) body in its utmost natural state.

Feelings of discomfort, tension and fear prevail in Karlson’s sculptural works. In her installation Drama is in your Head II (2013), ghost-like creatures are pushed into the corner, seemingly trapped within their bodies and minds. The robust concrete emphasises the heaviness of these bodies, weighed down to the ground. The artist staged her installation Family (2019), three concrete bodies, a child and its parents, with crooked smiles on their faces, in a more humorous way. These devilish life-size creatures are welcoming and warm, inviting us to join them in an over-lit clinical environment. A framed assemblage depicting a traditional model family, with mother, father and their two happy children playing in a colourful living room, is placed in the lap of one of the parents. Although it is clear that the two families are distinctly different, the tiny framed assemblage is taken as an example to look to.

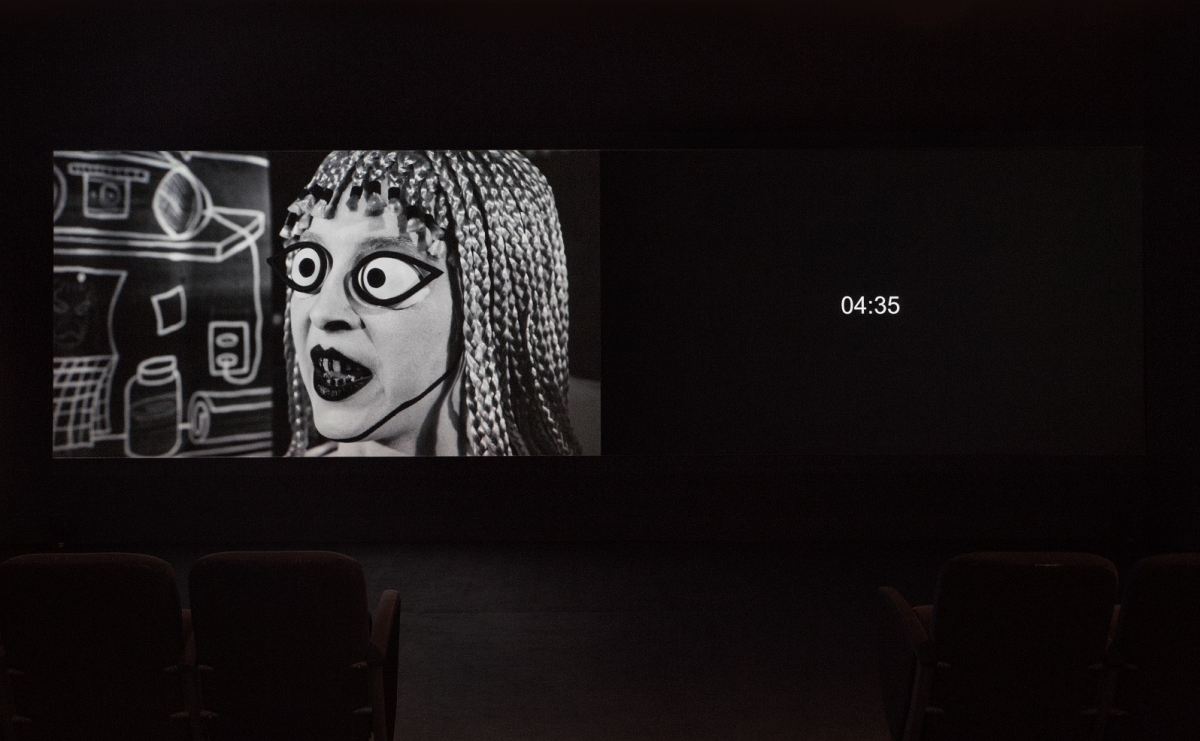

Mary Reid Kelley & Patrick Kelley. The Thong of Dionysus. 2015. Still from the video. Courtesy of the artists and the Pilar Corrias Gallery

Zombies, beasts and cartoonish monsters are also recurrent motifs in Mary Reid Kelley’s films, portrayed by the artist herself. Her Borges-like labyrinthine films have a rather mischievous quality, staged like a monochrome painting, similar to a black-and-white silent movie. Reid Kelley’s film You Make me Iliad (2010) is full of literary allusions, stylistic references to absurdist theatre, word play and visual irony.[4] It is a brilliant appropriation of our cultural past, bearing witness to the invisibility of the woman’s role and the absence of female creators in great historical narratives.

Mary Reid Kelley’s films, often made in collaboration with her partner Patrick Kelley, are inspired by myths, literature and historical events, and based foremost on the artist’s fantasies. In her work, women become the central characters and spokespersons of dramatic events that happened in the past. This is Offal (2016) is a film that whirls around the autopsy of a drowned woman. With allusions to Thomas Hood’s poem The Bridge of Sighs (1844), and to Andrew Marvell’s Dialogue Between the Soul and the Body (1681), it evokes a comic grotesque setting, in which disembodied internal organs engage in a verbal slanging match over the victim’s corpse. The tragic words by the heroine I feel ya, Ophelia continue to echo after leaving the exhibition space.

The show Do Come in, the Door is Open! points rather ambivalently to the tyrannies of our times, bringing to light personal and intimate stories told by the three female artists. Through the works of Mustonen, Karlson and Kelley, it becomes apparent that devilish demons live mostly in our heads. Wicked beasts creep silently but resistantly under our skin, and they grow into monsters before we even notice it. In order not to be pushed into the abyss, we can outdo and trick these mischievous demons. After all, a hazardous destruction and perilous explosion can be turned into a graceful victory.

Photo documentation of the show you can find here.

[1] Triin Tulgiste, exhibition text of Do Come in, the Door is Open! Edith Karlson, Mary Reid Kelley and Eva Mustonen, Kumu Art Museum, 2019.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Fanny and Alexander, film and television series directed by Ingmar Bergman, 1982.

[4] Kate Forde, ‘Mary Reid Kelley’, Frieze, Issue 135, Nov–Dec 2010.