Jung Hsu is a Berlin and Taipei-based media artist whose practice integrates interdisciplinary knowledge with artistic research, crafting heterogeneous encounters that respond to contemporary social situations. Her work often employs metaphorical objects to construct speculative scenarios, offering multiple perspectives on pressing global issues. A Golden Nica winner of Ars Electronica 2022 and the Art & Science awardee of Falling Walls 2023, Jung has also been recognised by Tagesspiegel as one of ‘Die 100 wichtigsten Köpfe der Berliner Wissenschaft’.

Currently engaged in the SODAS 2123 residency, we had the chance to explore Jung Hsu’s perspectives on combining art, science and technology, and her approach to interdisciplinary collaboration. In the interview, she delves into how metaphorical objects and speculative scenarios bridge these domains, offering unique ways to address complex social and environmental issues.

Jung Hsu receiving Golden Nica. Photo: TAICCA

Rosana Lukauskaitė: Your work often combines art with science and technology. Can you tell us how you bring these different worlds together in your projects?

Jung Hsu: Art and science, in my view, aren’t as distant from each other as they might seem. Both are deeply human pursuits, born from our innate desire to understand the world and to communicate our understanding. Science seeks to explain phenomena, while art offers ways to express and share those understandings, often inspired by the same sources. I approach my projects by exploring different perspectives, aiming to find connections between seemingly unrelated contexts. A single fact can manifest differently, depending on the framework in which it’s viewed, and discovering these reflexive connections, where one idea resonates within another, helps me bridge the gap between art, science and technology. It’s about weaving these perspectives into something coherent, yet open to interpretation.

RL: Winning awards like the Golden Nica of Ars Electronica is a huge accomplishment. How do these recognitions inspire or challenge you to keep pushing at boundaries in your art?

JH: When I first learned that ‘Bi0film.net’ had won the prize, I went through an intense bout of imposter syndrome. It was surreal, especially since the project emerged from such a collaborative and deeply personal process with Natalia, who continues to inspire me in profound ways. Over time, I’ve come to see the award as a celebration of our shared work rather than a measure of individual merit. The recognition has given us opportunities to present the project in various contexts, sparking dialogues that reaffirm the importance of collaboration and embracing difference. It also pushes me to keep questioning and exploring, especially on themes like biopolitics, which demand ongoing, dynamic engagement.

RL: Your project ‘Bi0film.net: Resist Like Bacteria’ draws inspiration from bacterial communication. How do you use biological processes as metaphors for civil resistance, and what has been the public’s response to this unique approach?

JH: The feedback has been fascinatingly diverse. Many have noted the project’s non-visual aesthetic, which challenges traditional expectations of art. Others have described it as functional, poetic, rhetorical, and even techno-optimistic or anarchic. Some find it thought-provoking, but acknowledge that it requires significant background knowledge to fully grasp its depth. One of the most rewarding moments was hearing from individuals seeking support for autonomous networks in their own contexts, validating the project’s practical and symbolic resonance. This diversity in reactions reflects the project’s intention, to provoke dialogue about non-human perspectives and alternative forms of resistance.

‘Bi0film.net: resist like bacteria’ Photo: Juan Diego Rivera

RL: You’ve lived and worked in different cities, like Berlin, Taipei and Shanghai. How have these different cultures influenced the way you think about and create art?

JH: Each city represents a distinct reality, shaped by its unique social, historical and cultural fabric. Experiencing these differences has expanded my perspective, helping me see how the same ‘facts’ can be understood in vastly different ways, depending on the context. This awareness sharpens my curiosity about the narratives that underpin our understanding of truth. It also challenges me to approach my work with greater sensitivity, and to embrace the complexities of multiple, sometimes conflicting, realities.

RL: In your project ‘Microbiopolitics’, you map out the human microbiome to explore the relationship between humans and microorganisms. How does this project reflect the tension between our desire to control our bodies and the complex, often unpredictable, nature of the microbial populations within us?

JH: This project stems from personal experience, as my own body’s sensitivity to microbes has forced me to confront the delicate balance within the microbiome. Years of infections and overuse of antibiotics and probiotics have shown me how easily this balance can be disrupted. Society’s pursuit of health and cleanliness often exacerbates this tension, creating conditions where microbial systems are thrown into chaos. Rebuilding that equilibrium is a slow, unpredictable process that underscores how little we truly understand about these interconnected systems. Our bodies aren’t isolated entities, but are part of a larger, interdependent web of life. This project highlights the futility of trying to impose control over such complexity.

‘Microbiopolitics’. Photo: Madoka Kitani

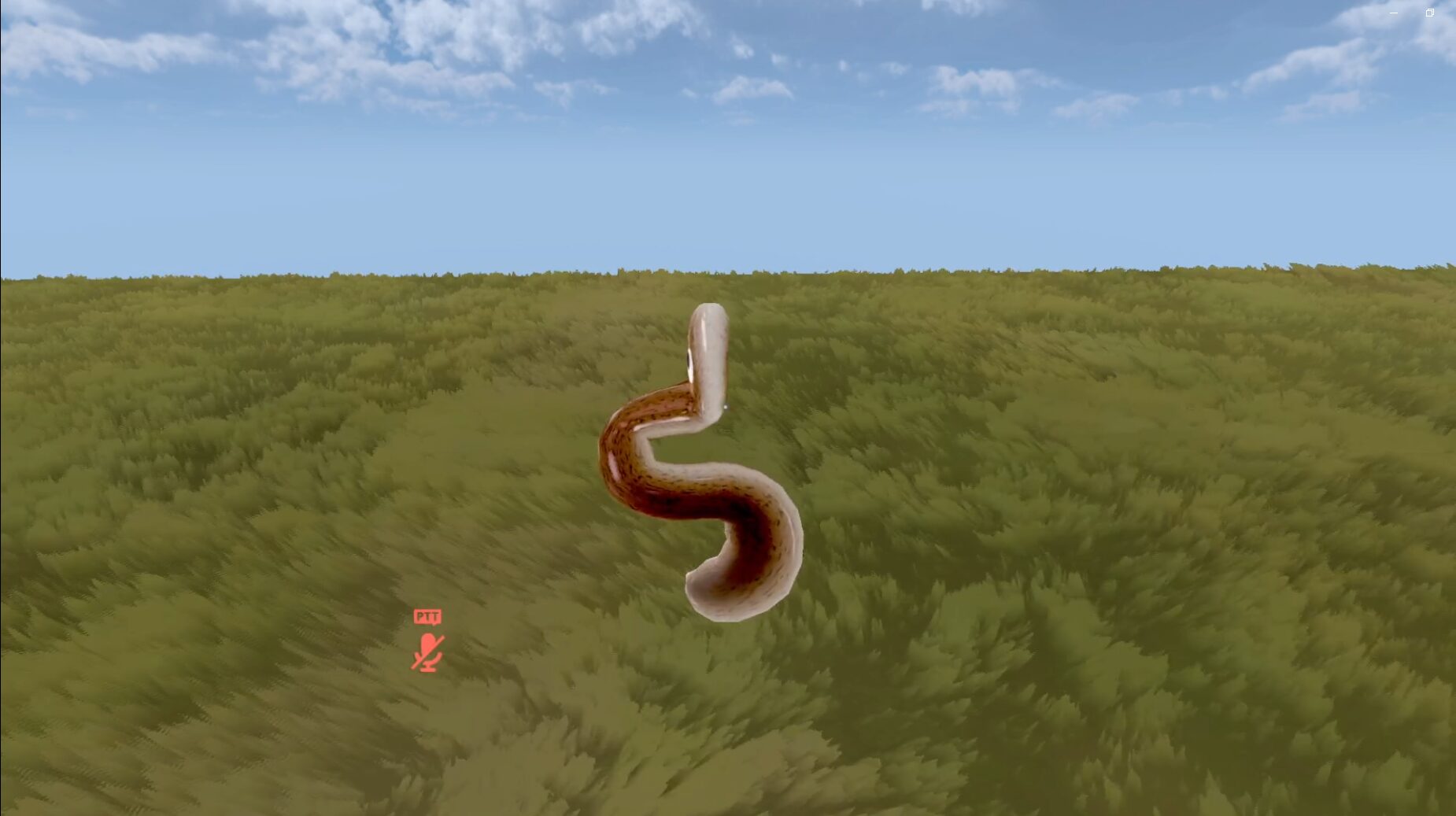

RL: Your project ‘How to meet out of now/here?’ explores the concept of Nepantla within the VR chat world. How does this hybrid virtual space help individuals navigate their complex identities, and do you believe VR can truly provide a ‘borderland’ for those who feel marginalised in society?

JH: The VRChat world offers a small window into the broader possibilities of online platforms for identity exploration. It creates spaces for diverse communities to express themselves in ways that physical spaces might restrict. The Internet already allows us to navigate identity in a more fluid way than before, and VR adds an extra layer of embodiment to that experience. While VR can’t fully replicate the nuances of real-world ‘borderlands’, it provides a powerful metaphorical space for those seeking refuge or reconnection with parts of their identity. These spaces are not perfect solutions, but can be transformative tools for imagining alternative ways of being.

‘How to meet out of now/here?’ Photo: Maria Capello, Jung Hsu, Francesca Valeria Karmrodt, Won Park

RL: As someone who works across disciplines, do you think creativity thrives more in collaboration or in solitude? How do you balance these two dynamics in your own process?

JH: Collaboration is at the core of everything I do, even when I’m working alone. Research, reading and writing often involve dialogues with the work of others, ideas I engage with, adapt and build upon. Asking for help or feedback is a natural part of the process; no one can know or do everything on their own. Even the digital tools I rely on are products of collective outcome, open-source frameworks and libraries, I’m only an individual user of all these creations. I feel like I’m just doing something reflecting ‘the moment’. It’s not my own will, but a reaction to being part of a collective consciousness. At the same time, I value moments of silence and introspection, which allow me to process and synthesise these influences. For me, creativity is about finding a rhythm between these two states: solitude for reflection, and collaboration for growth.

‘How to meet out of now/here?’ Photo: Maria Capello, Jung Hsu, Francesca Valeria Karmrodt, Won Park

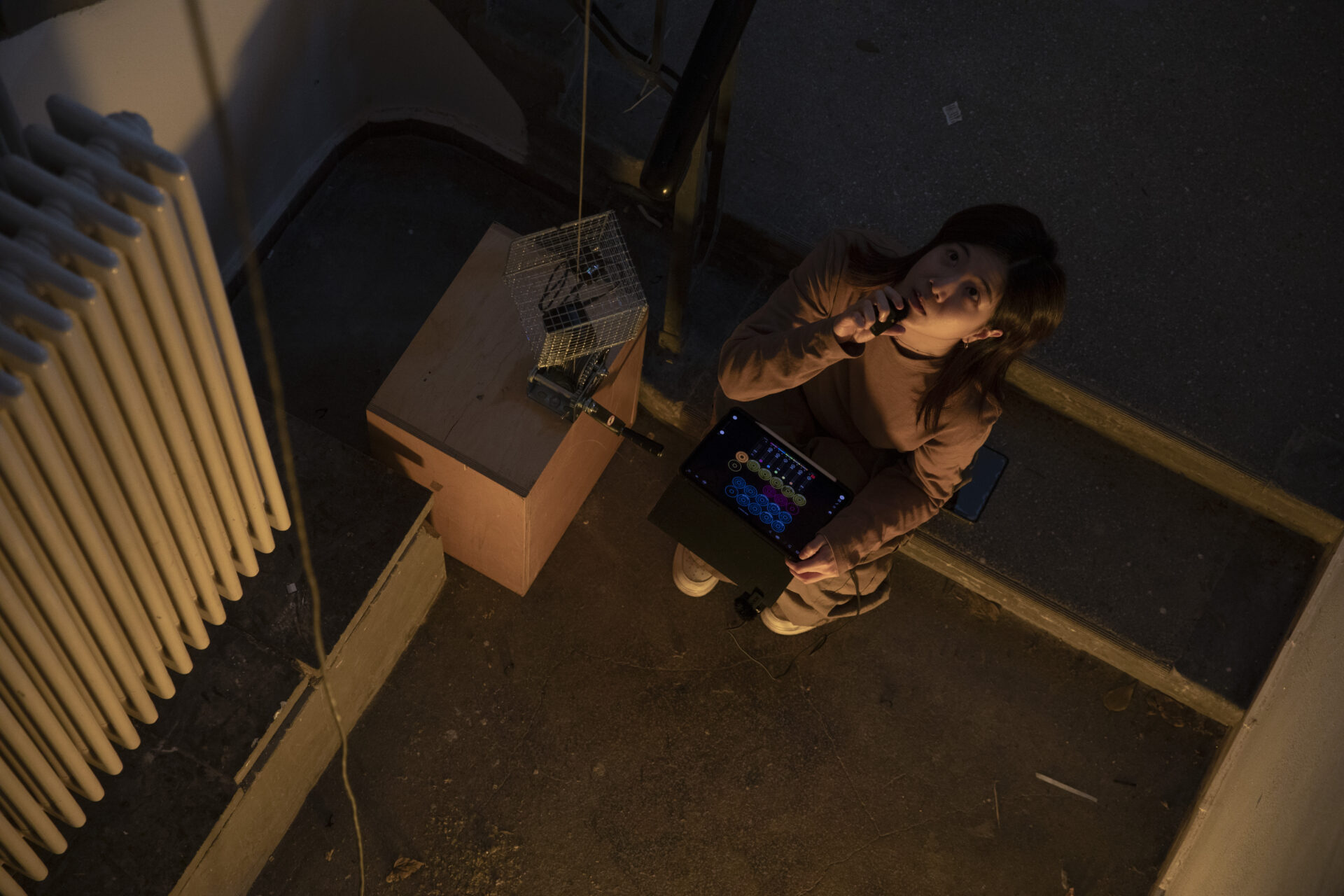

RL: In your project ‘Save a Dying Bird?’ you explore the shift in how humans relate to nature, from viewing it as a resource to feeling guilt and attempting to preserve it. With the canary as a metaphor, do you think our current environmental efforts are genuine acts of restoration, or are they more about easing collective guilt for the damage already done?

JH: My understanding of this question continues to evolve. Are we too late, or is it never too late? Beyond this binary, I’m particularly drawn to the emotions of guilt and mourning: where they originate and how they shape our interactions with nature. The canary has long been a symbol, carrying layers of meaning through history, from its role in coal mines to its status as an ecological metaphor. In manipulating and mourning nature, we create something that is no longer ‘natural’ in the traditional sense. This duality fascinates me: the canary as both a victim of human actions and a projection of our societal struggles with responsibility and empathy. What does it truly mean to save something, and who or what are we really trying to save?

‘Save a dying bird?’ Photo: Maxim Tur

RL: In your downtime, when consuming media, are you able to fully immerse yourself for enjoyment, or do you find that your artistic and critical lens is always engaged, influencing how you process and potentially integrate what you see into your future projects?

JH: For me, the concept of ‘downtime’ feels almost non-existent: artists rarely truly switch off. While I can fully enjoy all kinds of entertainment, whether it’s a film, a game or a piece of music, there’s always a part of my mind quietly processing, analysing and connecting what I experience to my ongoing work. These moments of enjoyment often act as fertile ground for ideas, with every detail or narrative carrying the potential to inspire future projects. Even when I’m not actively thinking about my work, the experiences I consume inevitably become seeds, waiting to sprout in unexpected ways. Creativity, in this sense, is a constant undercurrent, blending enjoyment with reflection.

‘Save a dying bird?’ Photo: Madoka Kitani