The 12th winner of the Young Painter Prize will be announced on the 13th of November at the “Pakrantė” gallery in Vilnius. In the run-up to one of the most important painting events of the year in the Baltics, we asked Lithuanian art critic Viltė Visockaitė to share her thoughts on the contemporary painting, networked painting and about the union between painter and curator.

The question still remains: how to understand and explain contemporary art? Of course, you can feel it, although for an art critic that’s probably not enough. That is why this question is relevant not only for spectators and artists but also for professionals in my field – intermediaries between the work and the audience. In this text, I will attempt to unravel the knot of contemporary art by touching on the very era in which we live, the relationship of the work to the context, and the collaboration between artist and curator – and by doing so discovering at least part of the answer to the question raised.

Viscous Present

My intense attendance of exhibitions in recent years has drawn a map in my mind which unfolds lifelike paradoxes and the (un)truths of the modern world. Contemporary art draws us into its enchanting narratives of the present, increasingly moving us away from the comprehension of the whole. Therefore, modernity, or the present, is one of the categories that enable us to talk about contemporary art. Peter Osborn describes modernity as a useful product of the imagination that links global, unrelated contemporary stories. Boris Groys, meanwhile, argues that modernism sought to bypass the present by shaping the future. Modernity, conversely, is understood as an eternal procrastination[1]. Doubt, uncertainty and indecision are the hallmarks of the modern state – procrastination creates more time for reflection and deliberation. The present is not a transition from the past to the future, because the future and the past are constantly being rewritten[2].

In this context, St. Augustine’s famous conception on time becomes of especial importance. He argues that there are three times: a present of things past, a present of things present, and a present of things future. He explains that the present of things past represents memory, the present of this present is sight, while the present of things future is expectation[3]. A similar concept of phenomenological time was developed by Edmund Husserl who distinguished the chronological perception of time from temporality – the time of consciousness. Temporality manifests itself in the way that the present is affected by both the future and the past. The phenomenon itself consists of the initial impression, its projection into the near future, and the retention of the initial impression. We can observe that in the context of modernity, both the past and the future acquire meaning in the present. As Kristupas Sabolius observes, “in today’s art world a common element of uncertainty reveals both the impossibility of a homogeneous present and the postulation of the asynchrony of its different temporalities, while at the same time raising the problem of the nature of time itself” [4].

Let us recall the work of Andrius Zakarauskas – the first winner of the “Young Painter Prize”. The issues of painting as a medium, painting as a gesture (paint, its application, bright stroke) and the author-artist’s self-representation (at the beginning of his career the artist often depicted his image on canvas) are important in his work. Since 2016 the artist’s paintings have displayed a new plastic expression that is characterised by an excess paint, splashing, pouring and embossing. The latter aspects are also reflected in the titles of his recent paintings, where the word “stroke” is dominant (visible stroke, larger stroke, third wave stroke, lip stroke, caring stroke, pleasant stroke, etc.). Time is one of the tools that allow us to interpret the materiality of colour in Zakarauskas’ oeuvre. Such paintings as Lipstroke (2017) or Skinstroke (2016) function as an outline of a painting itself: a visible process, the traces of time, and behind-the-scenes creation – with the relief of the painting becoming equated with the stroke itself. The moment of the painter’s touch on the canvas is captured: the tactility of the work opens the viewer to the viewer, highlighting the elements of corporeality and ephemerality. The moment of the painter’s touch on the canvas is captured: the tactility of the work takes the gaze of the viewer to the past, highlighting the elements of corporeality and ephemerality.

Laisvydė Šalčiūtė, The Necessary Angel, 2018, 162×150 cm

Networked Painting

Having discussed the widely researched phenomenon of modernity, let us move on to the work of art and its circulation within various contexts. David Joselit in his book, After Art (2013) explains how a work of art operates in the (non)art world. He refuses to create meaning for the work, which is customary for an art critic, instead arguing that the value of the work is revealed in its context and network of interfaces. An image can be closed, inaccessible and without any interfaces, or conversely, an open and accessible image that has the power to reach a huge audience. Consequently, the more widely one can relate the image to different themes or contexts, the more valuable and relevant it is. Networked interfaces create possible contexts for a work of art, while the art itself is in constant flux, changing through the ever emerging new relationships between the work and its perceiver, gallery, fair, biennial, etc. All works of art in circulation acquire meaningful and valuable content simply because they can be rotated and linked to different contexts.

For example, an artist’s participation in a YPP competition is already the creation of one of the networks. YPP has been held since 2009 and gathers together young artists from Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. This means that information regarding this event reaches not only the local audience, but also other Baltic states; therefore, it has a positive effect on the Lithuanian art field, while the jury consists of famous representatives of this field from all over Europe. YPP becomes an apparatus that ensures the preparation of an exhibition catalogue, the opportunity for artists to participate in residencies, the ability to receive cash prizes and the organization of a personal exhibition. The work of the artist, having entered the YPP network, circulates in the field of art and thus accumulates symbolic capital.

In addition to the interfaces between the work of art and the institutions, the state and the global stage, the viewer’s experience and transformation while observing an art work is also important. An experience is defined as a memorable event that engages the viewer personally. While transformation is the effective consequence of such an experience, which alters the person themself, i.e. influences thinking. Thus, art is able to create transformative experiences. Dorothea von Hantelmann also speaks about the shift of meaning towards the perceiver. She proposes that the work of art becomes the operator of the viewer’s relationship with themself and others[5] – meaning arises within experience. As society has shifted from materiality (a society of surplus) to an evaluation of experience, it is not surprising that this also applies to art.

So how does painting belong to the network? As Joselit suggests, painting can visualise these networks. Thus the object of art encompasses several media, contexts and places. For example, in the Lux Interior (2009) exhibition, New York, Jutta Koether’s painting functioned as an installation, part of a performance, and a painted canvas. The painting Hot Rod (After Poussin) is a monochrome remake of Nicolas Poussin’s canvas Landscape with Pyramus and Thisbe (1651), in which the painting technique – hurried and inert – becomes of prime importance and is used to mark the elapsed time between the paintings of Poussin and the artist herself. Moreover, the work was accompanied by three lecture-performances – with the painting thus becoming an artist’s interlocutor and a participant in the performance[6]. The artist actualizes the operation of the object in the network: the canvas embodies the dimension of time and at the same time becomes a part of the performance.

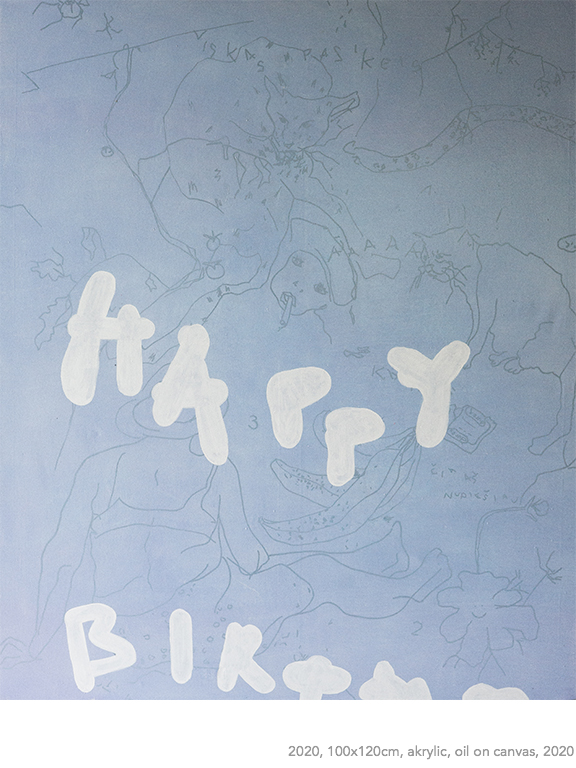

In this case, painting as a medium, painting as a social network, or painting as a relationship with the body opens up new opportunities for interpretation. Painting can become a point of intersection within installations, performances and other media. For example, in Gintarė Konderauskaitė’s work, one can spot “painting” with a finger – the painter makes a sketch on her phone and transfers the exact same image that is “painted” on the phone screen to the canvas. Thus, the traditional painting technique of oil painting and the digital drawing merge on the canvas. Meanwhile, the canvases by Elena Antanavičiūtė with their translucent layers create the volume of the body – the shades of soft grey, brown and pink contrast with the brightness of a body contour, as if saying although “hardly visible” – “I am”. The painter acquires corporeality through the thinness of the paint and its visible materiality, thus revealing the body’s relationship with time – skin pigmentation, stretch marks or wrinkles are layered over with oil paint. Therefore, the painting creates shapes and structures that enable the visualisation of the network, i.e. interfaces with digital images, the media itself or your own body.

Gintarė Konderauskaitė, 2020

The Painter and Curator Union

In this section, I would like to discuss the union of curators and artists that is taking root in the contemporary art market. Although art survived without a curator for 5000 years, the 21st century curator – independent of the institution – has become a figure of particular importance in the modern art world. Harold Szeeman, one of the first independent curators, contributed to this by starting to organize exhibitions that did not reflect the objective canon of art history, but rather the individual gaze of the curator. Dorothea von Hantelmann observes that, like the artist, who from antiquity to the 18th century was considered a craftsman, only to later become viewed as a creative genius, so the curator, seeking a place in society, has moved from their position of service provider to become a creator of content and meaning[7]. According to Georgina Adam, the curator now has the tremendous power to decide which artists are significant and which are not. Furthermore, the curator’s conception sometimes undermines the artist’s work itself, which becomes an adjunct to the curator’s vision[8].

However, a curator, enveloped in the knowledge of art history, can establish the artist’s work in a contemporary context, reveal the strengths of the works and present it all to the public. In this light, it is worth mentioning several personal exhibitions of Lithuanian artists that were curated by art critics. First of all, I would like to draw attention to the creators of the middle generation – Laisvydė Šalčiūtė and Laima Kreivytė. Kreivytė, who had curated a few of Šalčiūtė’s exhibitions, in 2019 invited to the space of the gallery “Left-Right”, with the gate to the Melusian Paradise being opened. According to the artist herself: “this cycle of works features the fictional antihero Meliuzina, whom I created myself, and who ironically and at the same time metaphorically talks about the social relations of our time, social status and anti-status to which she herself belongs; the theatrical mystifications of our consumer society and from it following tragicomic idiotism that is conditioned by the highest value of our consumer society – the pursuit of a “happy life”.” Although the works were first exhibited in the Palace of the Dukes of Mantua, the exhibition in the gallery was “constructed as a localized ritual” with Kreivytė herself assuming a position more akin to an architect than a curator. In the exhibition, the viewer immerses themself in a pictorial oasis, starting with “the earthier, more mundane narration of splashes in the bath <…> to a brighter hall with paintings containing recognisable paraphrases of the works of famous painters. Here, the Baroque is “barracked up”, the angels wear weapons, the toys, skulls and tattoos point to a secondary reality, or an otherworld, against which leans a white ladder”[9]. The viewer is intuitively led to the upper hall of the exhibition (not by chance), as if they were being elevated towards more universal themes relating to cosmogonic myth. In this way, the exhibition creates not only a narrative, but also a bodily experience of the concept that is formed by the architecture.

Detail from the exhibition ‘Hyperlink’ by Monika Radžiūnaitė. Photo: V. Nomadas

The exhibition “Hyperlink” (2020) at the gallery “Arka” put together by a duo from the younger generation – Monika Radžiūnaitė and Linas Bliškevičius – can be singled out as a counterweight to the art of the middle generation. By applying modern creative strategies, Radžiūnaitė revives the plots, symbols and iconography of medieval works of art. However, what has not been preserved by the written sources, the artist fills with the present and makes the images of the past relevant by passing them through a filter of ignorance or stupidity. In the exhibition, the artist’s works lurk in a darkened space in which small images have been stuck within various corners. The gallery’s precisely prepared walls respond to the thoroughness of the artist’s painting, while the works themselves are accompanied by texts selected by the curator – hyperlinks that create new connections and meanings. Both the artist’s work and curatorial solutions actualize the past, extend the present, and make online links the starting point of the exhibition. Consequently, by maintaining the balance of ideas between the painter and the curator, the exhibition becomes an organic art experience in which spaces, works, and narrative planes intertwine.

***

Contemporary art reflects on both current issues and the pulse of today, which we may not always be able to grasp. The artist, as if a mediator between us and time – visualises what at first glance might appear banal or boring – our everyday experiences, individual truths and sensations. The critical evaluation of an art work is possible only through interpretation – by analysing individual works and thus discovering new contours on the map of the modern world.

[1] Claire Bishop, Radical Museology, London: Dan Perjovschi and Koenig Books, 2013, p. 18.

[2] Boris Groys, „Comrades of Time”, in: E-flux journal, 2009, Nr. 1, http://www.e-flux.com/journal/11/.

[3] Saint Augustine, Confessions, Vilnius: Aidai, 2004, p. 281.

[4] https://artnews.lt/isivaizduojant-laika-39561

[5] Dorothea von Hantelmann, „The Experiential Turn”, in: On Performativity, Living Collections

Catalogue, 2014, t.1.

[6] David Joselit, „Painting Beside Itself”, in: October, 2009, Nr. 130, pp. 125-134.

[7] Dorothea von Hantelmann, „The Curatorial Paradigm“, in: The Exhibitionist, 2011, Nr. 4, p. 6.

[8] Georgina Adam, Big Bucks: The Explosion of the Art Market in the 21st Century, London: Lund Humphries, 2014, pp. 90-92.

[9] https://literaturairmenas.lt/daile/meliuzina-veidrodziu-karalysteje?fbclid=IwAR3vpZQe4AOHOYYIrLHkIHCVEP-wq_OcCBgt9AAGPXAbF1Yifv47z3MUQLA