Through breath smelling of alcohol, I’m shot with a cheerful ‘Why so serious?’ It’s early on a Friday morning, and I’m browsing at a newspaper stand, waiting for my flight to Reykjavik at Helsinki airport. I’m offended. I thought I was doing well enough, considering I only managed to get a meagre four hours’ sleep. The source of the question is troll-like man with a nice stocky body, a reddish nose, and a wide smile, who then, without asking if I’m interested, generously starts telling me about his latest adventures. He’s been living at the far end of northern Iceland for 15 years, manages a hotel there, loves nature and mountains, and is concerned, since the flow of Russian tourists dried up after the war started. Lastly, he strongly recommends I keep an eye on the Russian media, because ‘they talk about things our people do not dare to say’ and ‘in general, it’s such a pity what Estonia has come to!’ My allergy towards Estonian expat conservatism starts acting up, and I snap at him: ‘It’s very difficult to make a country better, when you, the finer sons of Estonia, run away!’ That makes him go quiet and he mutters: ‘You’re right about that.’

‘This exhibition stems from the surrounding darkness. It starts from the feeling that the world is crumbling in our hands, while a strong wind blows the last remains even further,’ begins the curatorial text of ‘Can’t See’, an exhibition in the Sequences art festival, curated by the Estonian Centre for Contemporary Art. Aimlessness, hopelessness and elusiveness are integral to contemporary life. I know that both me and my troll-like friend feel powerless against larger forces, but I also know that our reasons for this are not the same. Instead of the social side of it all, the exhibition focuses on the non-human micro and macro worlds through four chapters, entitled ‘Soil’, ‘Subterrain’, ‘Water’ and ‘Metaphysical Realm’, which are supplemented by artworks in the public spaces of the city of Reykjavik and beyond. The exhibition is a massive exercise in empathy, both for the curators and the visitors. How to think about the world from the perspective of someone or something else? How to let go of the brevity of human life as a measure for everything and dive into deep time?

I walk from my hotel to the curators’ tour at the Marshall House, where the chapters ‘Soil’ and ‘Subterrain’ are exhibited. Throughout the guided tour, I enjoy seeing how the four-headed band of curators, made up of Marika Agu, Maria Arusoo, Kaarin Kivirähk and Sten Ojavee, seamlessly give the word to each other. When one of the heads loses momentum, the next one takes over. Although the curators don’t quite agree with me, I still think that the shift that collective authorship creates is above all about values, and the organisational side comes second. Having done creative work both solo and as a member of a collective, I know that in the first case, I have an army of theorists and craftsmen behind me; by channelling their multifaceted contribution, I reach my (singular?) position as an author in the end. The same amount of work is needed to create an exhibition, an artwork or a performance, regardless of how the contributors sharing responsibility are labelled in the exhibition material. But what changes when a person is labelled as a co-curator, and not merely a communications manager or an assistant? In this exhibition, all the curators shared responsibility when it came to the concept and the selection of the artists, but they also took on various additional roles: some focused more on text, others on production and communication, etc. I feel that the horizontal decision of invisible authorship also resonates with the content of the exhibition, its focus on phenomena hidden from the human eye.

Alma Heikkilä, Installation view at the Soil chapter, Kling Bang, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Vigfus Birgisson

Looking at Alma Heikkilä’s work flashing decaying wood, showcasing the inside of a rotting tree stump, I have to remind myself that these kinds of invisible processes are not acknowledged equally by everyone. And if they are, it is often only on the surface. Something like this: an insect consumes wood in order to get nourishment. But no: an insect consumes wood to live, and at the end of its wonderful life, it becomes earth that grows wheat that becomes bread and beer on the table of the human animal, so that we can keep on living and eventually become earth, so that … At a recent family dinner, I had to argue that a tree in a city is not only a thing of beauty, an aesthetic object, it also has the function to offer shade, it is a living being that collects nutrients and water. This deep and empathetic desire to understand is reflected in Bjarki Bragason’s constellation of works that, in their own way, make up a eulogy, a hymn and a dedication to a tree alongside which he grew up, and which will now soon be cut down. Coming as I do from a country that is profiting from its forests in a very short-sighted way, the story of a single tree on this rocky and moss-covered island, where the forests disappeared centuries ago, seems even more tragic.

Yes, ‘Can’t See’ dreams of giving a voice to non-human perspectives, but we can never really step outside our humanity. So artworks by human artists are still based on their experience, that is, they stem from humans’ desire to understand the non-human, to empathise with their strange being. In one of his essays, the writer Paul Kingsnorth expresses a longing for new literature that does not revolve around human characters, but trees and stones, so that our art would truly communicate the experiences of a variety of entities. Walking through the exhibition, I see that experimenting with this kind of embodiment is artistically a fascinating task, and, as I said before, worthwhile, as an exercise in empathy; but we also know that it is trees and stones that should write books on the eventful lives of trees and stones.

Saturday morning, it’s minus 0.5 degrees outside, and the water temperature of the Vesturbæjarlaug outdoor pool is approximately 30 degrees. I swim half a kilometre front crawl, my arms alternating between warm water and cold air. As I breathe in, the icy air grazes my throat, and soft but cold sleet falls on my back. After my work-out, I lounge in a hot water pool and watch children having a water fight in a shallow pool, sliding around. I am the only one wearing a hat, out of fear of catching a cold, making me an obviously inexperienced tourist.

Dozie Kanu, Precious Okoyomon

Defying the wind, I make my way through the narrow land bridge, exposed by the low tide, and towards the lighthouse on the island of Grótta, home to an installation by Precious Okoyomon and Dozie Kanu that makes the Icelandic wind visible and audible. The artists have hung lots of little bells around the lighthouse that make a sound in the wind. At the top of the lighthouse, we can hear the vibrations of the lighthouse itself, relayed by contact microphones. I hear somebody next to me mutter that the work is far too basic for an artist of such acclaim. I, on the other hand, enjoy moments where art is born seemingly out of nothing, but once materialised, shares the dramaturgical weight with planetary forces.

In the afternoon I stop by the Marshall House again, where Pola Sutryk serves (temporary) for ever soup throughout the festival, inspired by the Medieval tavern tradition of perpetual stew. I sip the broth that is still light in colour and substance, a bit of potato, celery, parsley, onion, but which should become increasingly darker and richer over the course of the festival. During dinner we discuss different Icelandic herbs and mosses, but also exchange knowledge about tastes in Poland and Estonia. Before I leave, I ask Pola whether she is planning to join us for the outing to Icelandic nature the following day, and as she shakes her head, I immediately understand the silliness of my question. The art of hosting lies in being present, and just as I had the good fortune to speak to her for a moment next to the pot of soup, the same lucky opportunity will be available to other visitors over the following days.

In the descending darkness of the evening, I reach Nordic House, where the third chapter of the exhibition, entitled ‘Water’, is. In the midst of the opening buzz, the artist Edith Karlson sits with her back turned towards the visitors and sings the popular Estonian song ‘Merepidu’ (Sea Celebration): ‘The sea always is, the sea always was, the sea always will be,’ surrounded by Anna Niskanen’s cyanotypes depicting waves on the walls and her own work Can’t See (which also gave its name to the exhibition). She performs the whole song bravely for the audience, and I feel a strange, even petty, joy rising within me. On one hand, because in addition to the curators, I am one of the few people in the exhibition space who understand the lyrics of the song. But also because I know that it is written by Kihnu Virve, an Estonian folk singer, who also did not live on the mainland, surrounded by the sea on all sides. The water chapter left the deepest impression on me, although I suspect this was because of the space and the rhythm of the exhibition, rather than the artworks. Around the corner from Niskanen’s work, I sniff around Kärt Ojavee’s installation made of glass, silver and incense. Wandering around the exhibition, I find myself coming back to it to inhale the next breath of air.

The other artist whose work I visit several times is Naima Neidre. Her three small pictures, two etchings and a drypoint, establish themselves among the other works with a mysterious harmony. I can’t really find the right words to describe the works, even now, a couple of weeks later. I tried to escape them, to focus on other pieces, but as soon as they flickered in the periphery of my visual field, I felt them call, and gave myself to them again. Including the older generation of Baltic artists is definitely one of the most worthwhile choices the curators made. Even though intergenerational dialogues have been curated in exhibitions with increasing interest and sensitivity, at least in Estonia, in recent years, this direction acquires an international dimension in Iceland, it reaches maturity. (Are we really at a point where we can move on from the generational conflict?) In addition to Naima Neidre, other chapters included works by Elo Järv, whose work is truly thriving at the moment (although posthumously), and is exhibited at two exhibitions in Tallinn, and the Latvian artist Zenta Logina, whose abstract paintings and textiles are inspired by cosmic larger-than-man phenomena and processes.

Quite far from the centre, in Reykjavik distances, that is, behind the airport, stands the black box venue Post-húsið, which, I’m told, is so alternative that a large part of the local art crowd has not visited the site yet. I can feel the hot sauna in the air and around me, beers are opened with a hiss and a click. When the time comes to begin, we are led into a space that has been transformed to such an extent that I need to look up towards the lighting rails to remind myself that I’m actually in a room that’s designed for Johhan Rosenberg’s traps, and not some kind of rat’s nest. In the second part of the performance, Rosenberg invites me to grab his little finger, which I do, and follow him. I and four other members of the audience become participants in the birthday party of the character he has created. To each of us, the birthday boy assigns a pose or a task. My body starts to tremble anxiously and my little finger that I try my best to hold out straight, starts curling up like a snail shell. Before the party ends, Rosenberg raises his little finger in a meaningful gesture, looks at me and says: ‘We rule!’

I begin my Sunday also swimming, this time in the centre of the city, at the Sundhöllin pool. Once again, I take pleasure in the contrast of cold wind and warm water on my body, and once again I am the only one wearing a woollen hat in the hot water pool. Soon afterwards, I sit in a bus, waiting in front of the pool. Guided by the artist Edda Kristín Sigurjónsdóttir, it takes me and my travelling companions, artists, curators, visitors, locals and journalists, on a round trip outside Reykjavik, into Icelandic nature. Our first stop is a work by Þorgerður Ólafsdóttir. Ólafsdóttir is one of the few people who has visited the island of Surtsey which formed in the 1960s after a volcanic eruption. Access to the island is strictly limited, so it is possible to observe how the newly formed land is colonised over time by various organisms without human intervention. The artist brought back from the island probably the first human footprint ever made on the island, now cast in a mix of concrete and rubbish found in the ocean, and placed on top of a concrete column on a high cliff. The island should normally be visible from that viewing point; however, today the sea is cloaked in a thick fog. Walking around the sculpture, I feel how the porous and fragile volcanic rock crunches under my feet, and I remember the embarrassing question I asked my taxi driver after landing: ‘Do you also grow potatoes here?’

Ragnar Kjartanson performance as part of the durational work by Edda Kristin Sigurjonsdottir, Sequences XI Can´t See. Photo Kent Märjamaa

My question is answered at our next stop, the Agricultural University of Iceland, where our tour guide Edda studies sustainable agriculture. We are offered local produce, including a tasty lunch made of potatoes, carrots and tomatoes. For dessert, we are directed to a greenhouse next-door heated with geothermal energy, where each of us is given a tiny piece of chocolate and a glass of wine. With the bittersweet treat in my mouth, I walk in the warm crystal palace and admire the bananas, pomegranates and citrus fruits growing there. I hear beautiful music somewhere far away, and as I move closer to the source, I see Ragnar Kjartansson in a pink silk scarf, singing and playing the guitar, surrounded by lush leaves. A day earlier, when I visited Reykjavik Art Museum, I was completely enchanted by his video Sorrow Conquers Happiness, and now he is standing right here in front of me. The rest of the day passes as if in a fog, and I think I’m not the only one, the whole group seems blown away by the field trip. I visit the opening of the fourth chapter, ‘Metaphysical Realm’, at the National Gallery of Iceland, and enjoy very much the performance by Bendik Giske and Ulfur Hansson, but I feel I am not quite present; instead, my mind is still wandering in the greenhouse among bananas with Edda and Ragnar.

The last morning. I don’t have time to go swimming today. I don’t even manage to have breakfast before I hop in my taxi. Luckily, all brave Estonian journalists are provided with a banana and a muesli bar. Munching on my spartan meal, I lean my forehead against the cold glass and take a last look at the equally spartan landscape. We drive just as the sun is slowly coming up. We begin the drive from pitch-black Reykjavik, and half an hour later arrive at the airport accompanied by the first rays of sun. Although the Nordic twilight feels like home to me, it still astounds me almost every time, as if I’m experiencing it for the first time in my life. Strolling towards the airport security check, I feel a pleasant surge of melancholy, and I begin to doubt whether I can separate the experience of the exhibition from that of Iceland itself in my article. On the plane, I read the first sentence in the catalogue, and realise that there really is no point in trying.

Installation view at the Subterrain chapter, The Living Art Museum, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Vigfus Birgisson

Alma Heikkilä, Installation view at the Soil chapter, Kling Bang, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Vigfus Birgisson

Anna Niskanen and Edith Karlson. Installation view at the Water chapter, The Nordic House, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Petur Thomsen

Brak Jonsdottir. Installation view at the Water chapter, The Nordic House, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Petur Thomsen

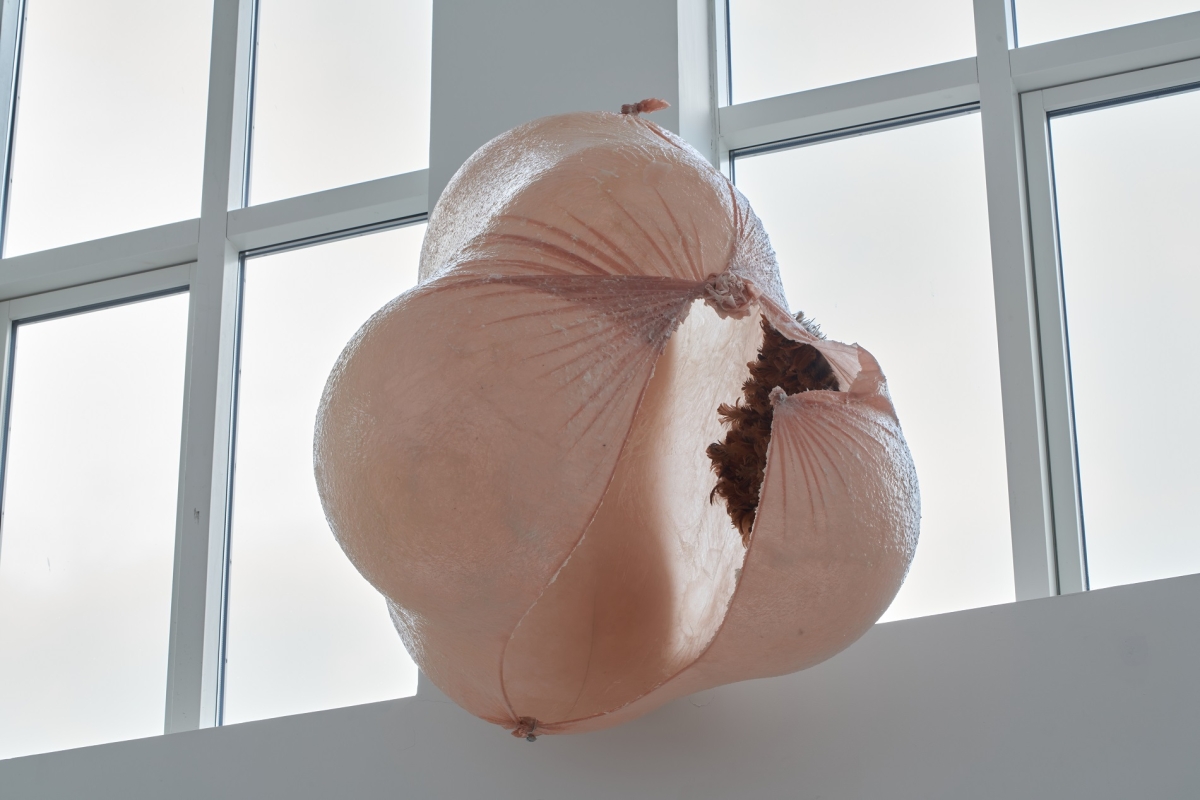

Daiga Grantina. Installation view at the Subterrain chapter, The Living Art Museum, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Vigfus Birgisson

Elo Järv. Installation view at the Soil chapter, Kling Bang, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Vigfus Birgisson

Emilija Skarnulyte. Installation view at the Water chapter, The Nordic House, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Petur Thomsen

Gerdur Helgadottir and Zenta Logina. Installation view at the Metaphysical Realm chapter, National Gallery, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Vigfus Birgisson

Gerdur Helgadottir. Installation view at the Subterrain chapter, The Living Art Museum, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Vigfus Birgisson

Gudrun Vera. Installation view at the Water chapter, The Nordic House, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Petur Thomsen

Icelandic landscape as part of the durational work by Edda Kristin Sigurjonsdottir, Sequences XI Can´t See. Photo Kent Märjamaa.

Installation view at the Metaphysical Realm chapter, National Gallery, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Vigfus Birgisson.

Installation view at the Soil chapter, Kling _ Bang, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Vigfus Birgisson

Installation view at the Subterrain chapter, The Living Art Museum, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Vigfus Birgisson

Installation view at the Subterrain chapter, The Living Art Museum, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Vigfus Birgisson

Installation view at the Water chapter, The Nordic House, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Petur Thomsen

Installation view at the Water chapter, The Nordic House, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Petur Thomsen

Johhan Rosenberg performance Traps at Sequences Can’t See. Photo by Olof K Helgadottir

Jussi Kivi. Installation view at the Subterrain chapter, The Living Art Museum, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Vigfus Birgisson

Kadri Liis Rääk. Installation view at the Subterrain chapter, The Living Art Museum, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Vigfus Birgisson.

Katja Novitskova. Installation view at the Water chapter, The Nordic House, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Petur Thomsen

Monika Czyzyk. Installation view at the Subterrain chapter, The Living Art Museum, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Vigfus Birgisson

Zenta Logina. Installation view at the Metaphysical Realm chapter, National Gallery, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Vigfus Birgisson.

Darja Melnikova. Installation view at the Metaphysical Realm chapter, National Gallery, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Vigfus Birgisson.

Naima Neidre. Installation view at the Water chapter, The Nordic House, Sequences XI Can’t See, photo by Petur Thomsen.