On the over 30-hour-long journey home from Brazil to Lithuania, the question of how to write about the Bienal de São Paulo, a huge contemporary art exhibition taking place in a little-known context, never left my mind. The exhibition features over 1,000 works by 120 artists, only a few of whose names I had ever heard of, and even fewer whose work I had seen before. The reassuring thing is that the concept of the biennial legitimises all possible narratives and ways of experiencing the exhibition, as the curious eyes of visitors, including mine, move choreographically over the undulating surfaces of the exhibition architecture. I have decided to start at the beginning, i.e. the facts.

Taking place this year for the 35th time, the Bienal de São Paulo is the largest biennial and the most important contemporary art event in the Southern Hemisphere. It is also one of the oldest art biennials, after the Venice Biennale, first held in 1951 at the initiative of the industrialist Ciccillo Matarazzo, with the aim of spreading ideas in contemporary art in Brazil. Soon afterwards, in 1957, a special exhibition pavilion was built in Ibirapuera Park, designed by a team led by the architects Oscar Niemeyer and Hélio Uchôa. Since then, the Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion, which covers 30,000 square metres, has been the venue for the main events of the Bienal de São Paulo. Interestingly, this biennial, like the Venice Biennale before it, had national presentations (for which it has been the subject of much justified criticism), which in 2006 were abandoned for socio-political reasons.

Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion, Ibirapuera Park, São Paulo, 2023

Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion, Ibirapuera Park, São Paulo, 2023

During my visit to the biennial, the speeches by the architects, the biennial director, one of the curators, and other members of the team, about the process of making a huge exhibition happen, conveyed a message that is rarely heard: not the usual ‘we know what we’re doing’, but the longed-for (at least by me) ‘we believe in what we are doing’, and we trust the people with whom we are doing it, thus opening up possibilities for experimentation and discovery within the vast mechanism, which are intended for a local audience first, and then for international visitors.

It seems that one such experiment was the choice of the curators for the 35th Bienal de São Paulo. Four curators were invited to curate this year’s biennial: Manuel Borja-Villel, a former director of the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid, the artist Grada Kilomba, the independent curator and writer Diane Lima, and the anthropologist and curator Hélio Menezes. None of the curators took a central role in developing the exhibition, and it seems that they did indeed succeed in their goal to become a functional collective where ideas can be developed individually. According to them, the principle of the practice that guided them was an attempt to dismantle the hierarchies and ethical and normative procedures that legitimise the vertical institutional structures of power, value and violence that the contemporary world is increasingly rejecting. Entitled ‘choreographies of the impossible’, according to the curators, the biennial ‘seeks to create spaces and times of perception that challenge the rigidity of the linearity of Western time’. This is reflected clearly in the structure of this year’s biennial exhibition, which not only questions the linearity of time, but also rejects the axial narrative, allowing all possible and impossible stories to unfold freely, providing them with guidelines, but not trajectories.

It is time to go and look for the promised impossibilities … It seems that every time you enter the building, the biennial just hits you, and it is only after a few days of visiting that a map of the paths walked and the personal key points that make the heart beat faster begins to form in your mind. There are more such points than ever. The curators of the biennial have succeeded in creating an exhibition that speaks articulately about the problems of today’s world, important phenomena that have shaped and continue to shape the fates of individuals and of entire countries, nations and communities, about traumas, their consequences and healing mechanisms, and about the possibility of changing attitudes and avoiding condemnation, but not underestimating the complexity of the problems.

Ibrahim Mahama, Parliament of Ghosts, Bienal de São Paulo, 2023

Kidlat Tahimik, Killing us Softly… with their SPAMS… (Songs, Prayers, Alphabets, Myths, Superheroes…), Bienal de São Paulo, 2023

The ground floor of the building is dedicated to installations, large both in scale and theme, which welcome visitors. The first work to catch the eye is Ibrahim Mahama’s Parliament of Ghosts, a project that combines a meeting space made of red bricks, adapted to the biennial’s educational programme, with the artist’s Parliament of Ghosts, created in 2019. Its base is ceramic vases and railway tracks brought from Ghana, recalling the history of industry and the crisis of industrialisation in colonial territories. Next to it is the installation ANTENA IA MBAMBE Mimenekenu Ê lá Tempo! by Anna Pi and Taata Kwa Nkisi Mutá Imê, which explores the phenomenon of the displacement of indigenous peoples, and encourages us to look for dialogue between different generations. Moving on, Kidlat Tahimik’s massive theatrical installation of monstrous wooden figures Killing us Softly … with their SPAMS … (Songs, Prayers, Alphabets, Myths, Superheroes …), overwhelms. The visual and narrative patchwork combines the indigenous mythology of Brazilian and Filipino people, stories of cultural genocide, eco-racism, colonialism, and much more. As Carles Guerra aptly writes in the biennial’s catalogue, Kidlat Tahimik’s installation makes you feel ‘like entering the junkyard left behind by all imperial regimes’.

Escaping the chaos of Kidlat Tahimik’s imagery, we are greeted by the installation Dawn (Kwema/Amanhecer), by the Brazilian artist, activist and fighter for the rights of indigenous peoples Denilson Baniwa. Baniwa’s installation is a corn plantation with a community gathering place around a cosmological stone, which seeks to remind us that, in an ever-changing world, sharing food, knowledge and community nourishes the mind and the body. After the biennial ends, there are plans to make a collective lunch from the corn and other plants grown in the installation. In the exhibition, the artist presents several installations that invite us to reflect on how industrial-scale agriculture on the lands of the Baniwa nation, which becoming increasingly intensive due to the support of politicians, is drastically destroying the rainforest and contributing to the climate catastrophe, as well as to reflect on the damage caused by monocultures.

Denilson Baniwa, Kwema Amanhecer, installation, Bienal de São Paulo, 2023

Climate change, ecology, the drastic exploitation of resources, and the related problems of local populations, are intensely discussed at the biennale. Julien Creuzet’s captivating installation Eternal Zumbi Zumbi invites us to take a look at the African diasporas on islands in the Atlantic Ocean. The work is full of visual, musical and textual references, the deciphering of which turns into an endless game, a political institutional critique, a rethinking of the issues of migration, ecology, and historical revisionism.

The American artists Edgar Cleijne and Ellen Gallagher propose to dive into an ocean that hides the consequences of colonisation, ecological destruction, capitalist infrastructure and tourism. Highway Gothic reveals the ecological, social and cultural impact of the US highway Interstate 10, which cuts through New Orleans and the Atchafalaya Swamp, on the local populations of the Chitimacha Indians and the Black neighbourhood of Faubourg Tremé.

Julien Creuzet, Eternal Zumbi Zumbi, Bienal de São Paulo, 2023

Julien Creuzet, Eternal Zumbi Zumbi, Bienal de São Paulo, 2023

Edgar Cleijne & Ellen Gallagher, Highway Gothic, 2023

Daniel Lie, site and time specific installation, Outres (Others), Bienal de São Paulo 2023

Meanwhile, in Daniel Lie’s meditative, site and time specific installation Outres (Others, 2023), the processes of birth and death are constantly interchanging. Composed of organic matter, plants, soil, seeds, fungi and various bacteria and micro-organisms influenced by the tropical climate, the work reveals itself anew every day. Fungi replace garlands of flowers, and delicate scents are replaced by the sweet smell of rotting and fertile soil. The processes of emergence, growth and disappearance, which are all equal to each other, broadcast to the viewer through all the senses the processes of change and the viewer’s own impermanence.

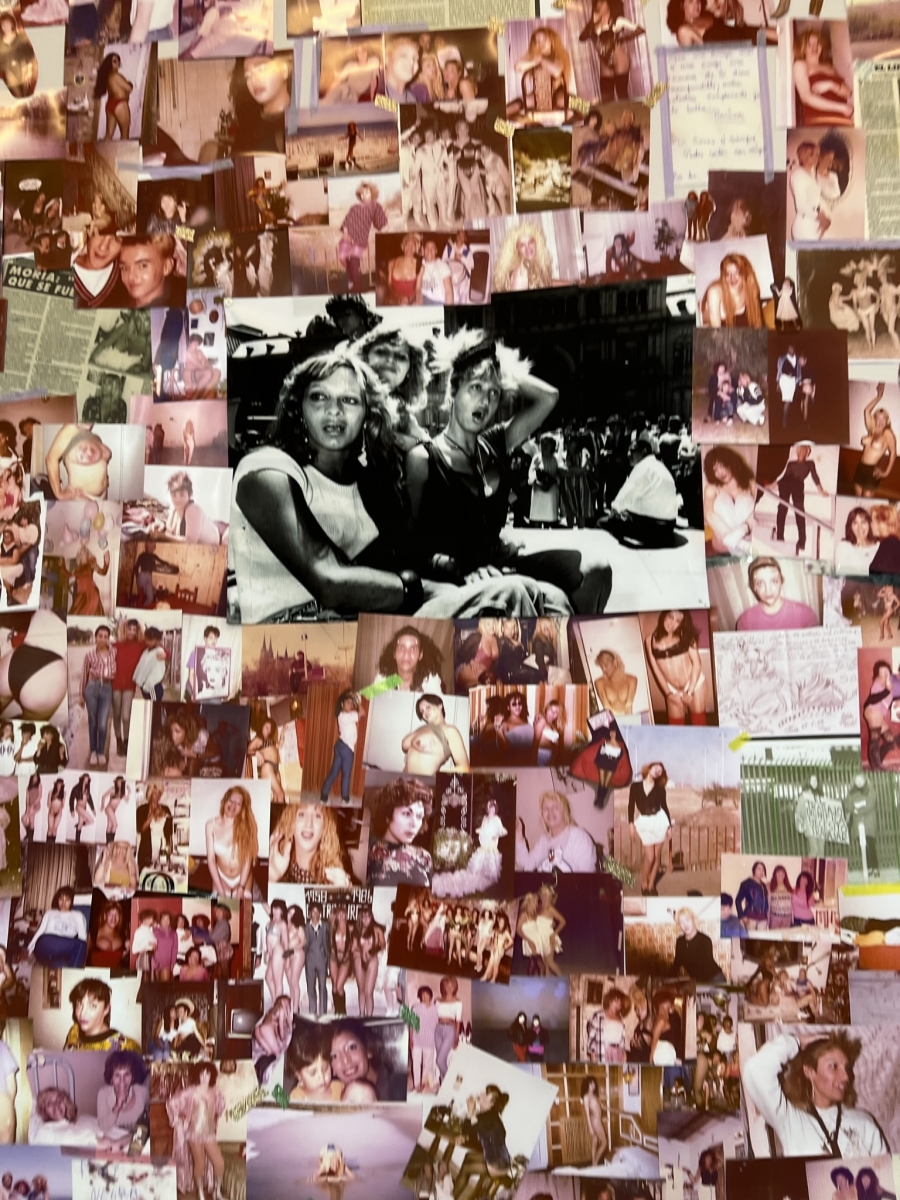

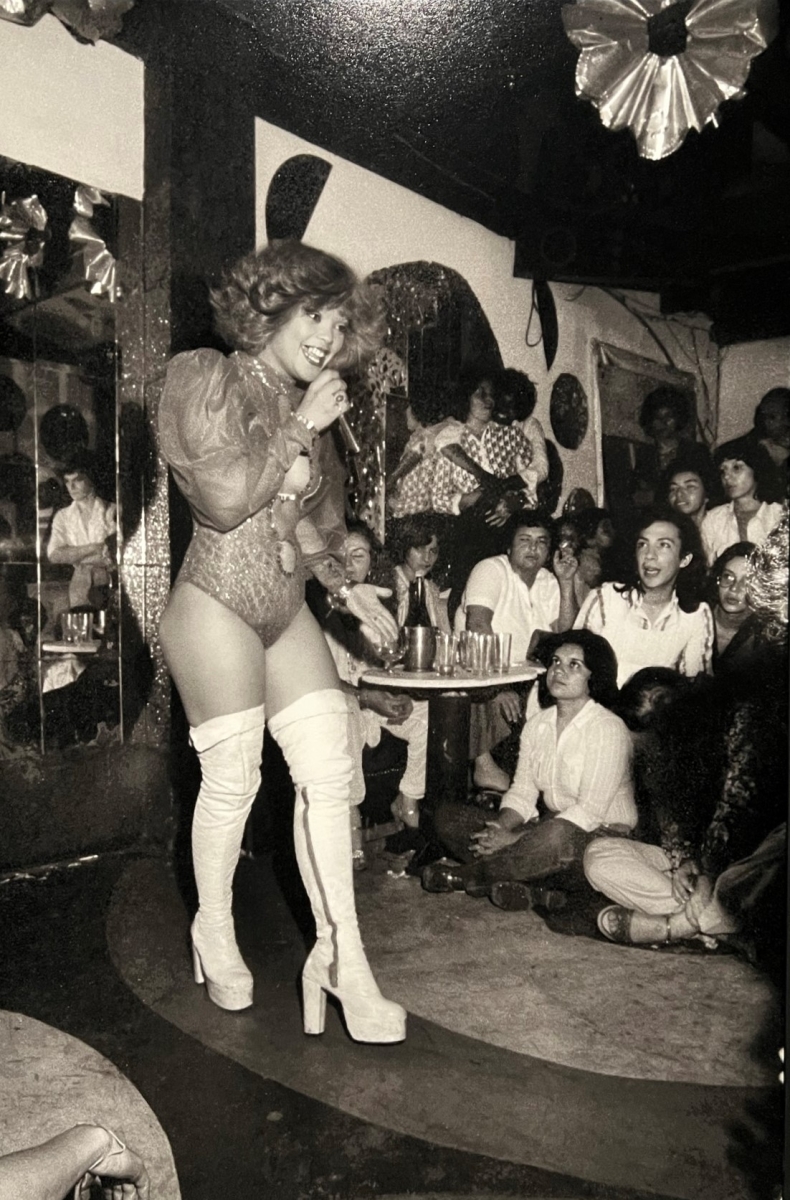

Many of the works discuss the history of colonialism, the forced displacement of people, repressions, trauma and the related search for identity today. The biennial also rethinks the history of South American art and artists’ resistance movements. ‘choreographies of the impossible’ also looks at issues of gender, transgender and homosexuality. For example, Archivo de la Memoria Trans, a project launched in Argentina in 2012, is an archive of the life events of transgender people that captures the joys and challenges of the community, and serves as a form of activism. The archive has collected about 15,000 items, with people sending in new ones every day.

Archivo de la Memoria Trans, 2012-…, installation, Bienal de São Paulo, 2023

Archivo de la Memoria Trans, installation detail, 2023

Marlon Riggs’ Tongues Untied (1989), a particularly candid, and in my opinion still highly relevant film, combines poetry, music, vogue performances and personal narratives to address the racism and homophobia faced by Black gay people. Leilah Weinraub’s emotional documentary Shakedown (2018) is about a Black lesbian strip club in Los Angeles. Rosa Gauditano’s photographic installation takes us back to 1979 at the lesbian Ferro Bar in São Paulo, which later became the focal point of the first lesbian demonstration against discrimination against women. The photographic essay talks about intimacy, the emotional bonds fostered in the bar, new family configurations, and political resistance to the repression of homosexual people.

Rosa Gauditano, Lésbicas, Bienal de São Paulo, 2023

Rosa Gauditano, Lésbicas, 2023

Many of the biennial’s works, including a number of video works, focus on the rituals, traditions, communal processes, crafts, languages and knowledge systems of indigenous people. The highly aesthetic work Ngā Whetū Maiangi o te Maramataka / As estrelas do amanhecer do calendário estelar lunar Maori, by the New Zealand-born Māori contemporary artist Nikau Hindin, revives the traditional Māori practice of making aute, a cloth obtained from processing mulberry bark, which disappeared more than a century ago. By recreating the ancient technique, the artist fosters the old world-view and endangered knowledge systems, as well as a reconnection with the ancestors.

Citra Sasmita, who comes from Bali, uses the Kamasan style of painting from the 16th and 20th centuries, which mainly depicted the exploits of men. However, the artist’s work inverts the usual iconography. Sasmita’s works are political, critiquing the stereotypical colonial gaze. They depict women both suffering and experiencing pleasure, their defragmented bodies merging into one and splitting apart again, transforming into trees and animals.

Rio de Janeiro-born Tadáskía presented a book of loose pages, Mystical Black Bird (Ave preta mística, 2022), turned into an installation. The circular space is filled with colourful drawings, including poetic bilingual texts, and three objects made of bamboo. Tadáskía dedicates the book to Black women, transgender people and Black outsiders, as well as to people who look after children or have the heart of a child, groups united by their vulnerability and environmental sensitivity.

Nikau Hindin, Ngā Whetū Maiangi o te Maramataka (As estrelas do amanhecer do calendário estelar lunar Maori), Bienal de São Paulo, 2023

Nikau Hindin, Ngā Whetū Maiangi o te Maramataka (As estrelas do amanhecer do calendário estelar lunar Maori), Bienal de São Paulo, 2023

Citra Sasmita, Timur Merah Project IX Beyond The Realm of Senses (Oracle and Demons), Bienal de São Paulo, 2023

Citra Sasmita, Timur Merah Project IX Beyond The Realm of Senses (Oracle and Demons), 2023, detail

Tadaskia, Ave preta mística Mystical Black Bird, Bienal de São Paulo, 2023

Unspoken expectations and sensitive personal stories are also the subject of works by two other women. The objects by Sonia Gomes, one of the most famous Brazilian artists of her generation, weave people’s stories, memories and feelings into the materials that people send her and the fabrics she uses. The themes of race, gender and temporalities are encoded in abstract objects. Sonia Gomes’ installation connects organically with the adjacent enigmatic sculptures by the American artist Judith Scott, which resemble mummies or cocoons. The artist used textiles, coloured yarn and other readily available materials to express feelings and states that she could not express in words. Judith Scott was born with Down Syndrome, was deaf, and spent most of her life in institutions. Her own thoughts remained uncommunicated, and her objects defy any classification system.

Sonia Gomes, Bienal de São Paulo, 2023

Sonia Gomes, Véu de Maia (série Pano), 2022

Judith Scott, Untitled, Bienal de São Paulo, 2023

The desire to enable different narratives, to reveal the diversity of coexisting realities, attitudes and states, is often embedded in exhibition concepts, but rarely realised. But not in this case. The biennial’s huge post-industrial glass pavilion, surrounded by a park on all sides, also dictates the conditions for experiencing the works presented. The collaborative work by the biennial’s curators and the Vão architectural team leaves an impression: unique and often successful solutions, and a space for the works to unfold that does not overwhelm or dominate, but allows for coexistence.

The Bienal de São Paulo invites you to hear the voices of those whose lives and stories have previously been excluded, and to rethink how to talk about decolonisation, environmental protection and resistance to oppression created by political systems in today’s art world. It is also about the consequences of the transatlantic slave trade, the forced displacement of people and forced takeovers of territories, refugee camps, the effects of ecological racism, the barriers between people and countries created by political decisions, issues of gender and sexual orientation, and a host of other issues that affect the whole world, but especially countries that are still labelled as ‘the global south’.

Torkwase Dyson, Blackbasebeingbeyond, 2023

Dayanita Singh, Museum of Dance (Mother Loves to Dance), 2021. Bienal de São Paulo, 2023

M’barek Bouhchichi, Nous sommes ce qui vous ne voulez pas voir, We are what you don’t want to see, 2023

Mounira Al Solh, installation at Bienal de São Paulo, 2023

Niño de Elche, An Invisible Sacramental Auto. A Sound Representation Based on Val del Omar, 2021. Bienal de São Paulo, 2023

The Living and the Dead Ensemble, The Wake, 2021. Bienal de São Paulo, 2023