Aap Tepper is an Estonian visual artist and photographer, the co-founder of art space ‘Rundum’ in Tallinn. Since 2016 he works in the Estonian Film Archives, so his artistic interest about the role of the archive in society, heritage, and collective memory is also understandable. Tepper’s artworks are part of the exhibition Digital Dark Age organized by Riga Photography Biennial – NEXT 2021, viewable in the Latvian Museum of Photography until October 3rd.

The conversation with Aap was mediated by technology – it happened digitally, not materially; screen to screen, not face to face. In a way it corresponds with the topics discussed – authenticity in reality and in a digital environment, the next level of the relationship between the original and the representation, subjectivity and its many expressions.

Rūdis Bebrišs: I’d like to begin by talking about your exhibition. The content of it is very closely tied to the work you do besides being an artist – namely, you also work in the Estonian Film Archives. The exhibition has great educational value and I feel like I truly learned something about what it means to archive things. But to start with two broad questions – what makes all of the exhibited objects art and what does it mean to you to be an artist?

Aap Tepper: I think it’s mostly contextual – it really depends on the purpose of the objects exhibited and the goal behind creating them. I’ll come back to this, but first – about the Film Archives. During my last year of master’s studies, I saw an opening there. I’ve always been interested in history and putting things in a wider context, seeing the reasoning behind different situations and events. For example, I took part in an artist-run space called ‘Rundum’ during my master’s – we did exhibitions in different locations that weren’t only white cubes. After master’s I did a curatorial internship in Berlin with ‘Neue Berliner Räume’, and they also put art in different contexts – they do exhibitions in buildings with a historic background that have stories to tell. This really inspired me, so when I saw an opening in the Film Archives, I was thinking that it might be a new place where I can go and learn and do my own art practice as well. I’ve been here for five years now, managing different archive projects, working with digitization and with databases. I’ve been experimenting with my position as an artist in the archives and using a lot of archival objects in my works.

To answer your questions, I think it’s all about the context and the way one presents different objects. If I showcase a record in the archives – it’s a record, but if I put it in the context of exhibition, it becomes something else. I think the keyword is “appropriation” – taking objects from one place and inserting them in another, playing with them in a way. Of course, if you’re working with materials with difficult backgrounds, you have to be careful – you must respect the items, know their background. You can’t just aestheticize something.

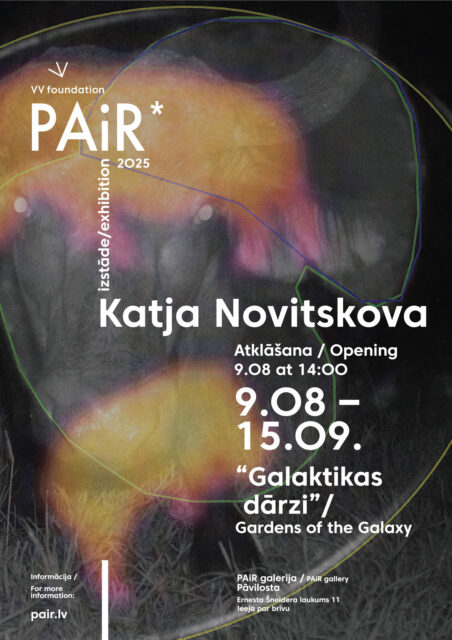

View from the exhibition “Digital Dark Age”. Riga Photography Biennial – NEXT 2021. Latvian Museum of Photography. Photo: Madara Gritāne

RB: So, would you say that the purpose of an artist in society – or maybe not exactly the purpose, but at least something that artists can do – is to provide a different look on things that we consider everyday objects?

AT: It’s a difficult, but important philosophical question – many of us, artists, define ourselves so differently. But I think art always comes from some kind of curiosity, and the function of art is shown by the way it resonates. Some artworks are just beautiful to look at, some artworks make you think. It’s hard to define.

RB: I agree about curiosity – that might be something that philosophy and art has in common… The name of your exhibition is The Shadow of Materiality – what does it mean and what does it refer to?

AT: The name comes from a quote by Joanna Sassoon – she’s a historian and an archivist, and she has an essay called ‘Photographic Meaning in the Age of Digital Reproduction’. The name refers to Walter Benjamin’s text[1], of course. She deconstructs the process of digitization; I like the way she phrases it: “What is produced in the process of translating a photograph from the material to digital is not an ‘echo of the original’ [referring to Benjamin’s text Task of the Translator], but a mere shadow of its former being.” This digital shadow obscures the processes that are important in physical objects, because when you digitize something, you are not creating an accurate representation of the object – it’s something that refers to the object. It’s like a shadow – it refers to something being there, but it’s only a projection.

I became very interested in this sort of institutional “competition” to digitize everything. On the one hand, it’s very important to make history visible, but on the other hand, the process of capturing images on older mediums was very different – bringing them in a digital context gives an appearance of an image, but it doesn’t talk about the social, contextual background that this image has. While doing this project, I wanted to look deeper into the cultural processes that go into digitization. It is a technical process, but first and foremost I think it’s cultural – it’s about the visibility of history, the archives communicating to the public. And it takes a lot of resources – many institutions must make choices about what materials to digitize, and these will be the materials that present certain collections to the public. Sometimes it’s only possible to digitize half.

There’s an important term in archival science called “provenance” – it refers to the context and physical background of an object. When something comes into the archives, not only the object needs to be documented, but the background of it as well – where it comes from, what is its past, how can we communicate it to future generations. I wanted to look at this digital representation system through another medium, so I chose ferrotyping as a method to showcase the process of digitization. It was a socially available method of taking an image from the late 1800’s to the early 20th century. I think it was a playful act to do this, but it also gave me a reason to contemplate the topic.

RB: I think using the plates was an interesting way to tackle the question about how technologies impact the way we archive things. But there is also a fascinating aesthetic or artistic side to some of the pictures. For example, it’s hard to describe the feeling of looking at a photography of a display that is editing another photography of a bonsai tree – if I counted correctly, those are three levels of representation in a single image. We’re going from reality to analogue, analogue to digital, digital to analogue again. It’s somewhat reminiscent of French philosopher Jean Baudrillard’s notion of hyperreality – namely, in a postmodern age reality as a whole is but a shadow of its former self. How could this transfer to an archival context? Is there anything authentic left? Materiality, perhaps?

AT: It depends on the things we talk about. In an archival context, materiality is very important. We’ve been digitizing heritage for at least 20 years, but the technology is constantly changing and we’re even starting to re-digitize objects. But there’s provenance of the physical and provenance of the digital as well – the context always needs to come with the objects that we are showcasing, and the descriptions need to be thorough.

Regarding authenticity – if we’re talking about social media and photography in a wider spectrum, I think you can’t really say that a digital or material/analogue medium is better, more authentic. It all comes down to preference. I’ve studied the history of photographic filters from their first appearance in photography to their use in social media. We could ask, for example – why do people like the “film look”? I’ve associated this with nostalgia that doesn’t have a referent, nostalgia without experience. With early smartphone cameras, this sort of effect helped alleviate the bad quality, make images look better. But I don’t think it’s only to do with nostalgia; taking another example – why do people still listen to vinyl? To me it seems more about enjoying the process itself – enjoying analogue photography, seeing how the picture is made and so on.

RB: There is a theory called metamodernism. It’s a sort of follow-up to postmodernism that states that we are not deconstructing things anymore, but rather striving towards authentic forms of expression. That could be a way to look at our age and interpret why some people are still interested in film cameras and vinyl – it’s a striving towards something real and material that seemingly brings authenticity with it.

AT: Sure – in social media these kinds of provocations of authenticity are always there. Communication of lifestyles, competition of whose lifestyle is more authentic. But I think the word “authenticity” has kind of lost its meaning somewhere along the way.

View from the exhibition “Digital Dark Age”. Aap Tepper’s (EE) exposition ‘Shadow of Materiality’. Riga Photography Biennial – NEXT 2021. Latvian Museum of Photography. Photo: Madara Gritāne

RB: Returning to the topic of your work in the archives – in your view, what does it mean to preserve history and to create an archive? Could we say that we are actively shaping history and heritage just as much as it shapes us?

AT: Yes, I think history is a constant representation and re-telling of a story, but the story changes throughout the process. That is one of the reasons why I came to the archives – I wanted to see how the elements of history are made. Historians read archival documents and different sources to write history, but in the archive you can really see these objects and the stories they have to tell, how they are used to create history. Taking an artistic position here, I think I have more freedom – I am not constrained to the discourse of history and its methodology. It’s very interesting to work with historians, but their way of working is more about telling a story through facts while implying objectivity. I embrace subjectivity while still respecting the background of records and creating critical gestures from that point of view.

For example, a couple of years ago I did a project here in the Film Archives – it was about the restriction of archives in the Soviet era and, more specifically, restricted photo albums from the first Estonian independence and the period before that. It was interesting to see that the images that were restricted weren’t only military photos or something that obviously had to be a secret, but rather pictures to do with ideology, such as images of boy scouts and other seemingly bourgeois civilian situations. I showcased landscape images from the formerly restricted photo albums in the Film Archives’ building, which was a soviet military prison before the archive moved in. I think these landscape images taken by people living in that era really showcased their subjectivity.

RB: Could we potentially consider archiving as saving the subjectivity of people?

AT: We could say so. When working with these restricted archives from the Soviet era and reading minutes from the archivists’ meetings, I was very interested to look at how people were trying to distance themselves from their subjectivities – the way of speaking was very formal. It’s interesting to see how people numb themselves – the biggest example, of course, being the practices and bureaucratic methods of Nazis, which helped some people justify their actions.

But regarding the archive itself – we say that we are an objective institution, that we don’t take sides and don’t have biases, but in reality every person has biases, regardless of whether they think of them or not. Archives are mostly about regimes and ideologies – ideology makes an archive and writes history. I think it’s also interesting to see the subjectivity of the people working there – of course, they care about what they do and don’t really talk about their ideologies, but they’re there.

RB: I agree that nobody’s free of their biases – it’s been a staple argument in philosophy for a while now and with the advent of postmodernism this has been brought in the methodologies of many disciplines, for example, history. History isn’t just a mirror of the past. It doesn’t find out, but rather explains. But regarding subjectivity – could we also call people’s posts on social media expressions of their subjectivity?

AT: I think so. Our subjectivities are constructs of other subjectivities. Social media is very dynamic and fast – people think less and less about posting something, it’s all part of visual language. Herd mentality is also present – you start to see trends that are connected to each other. For example, when studying Instagram filters, I came to the conclusion that the hashtag “#nofilter” is a filter itself, in a sense. I think the subjectivity is there, and it’s interesting to look at the different elements that construct it.

RB: Let’s tackle another section of the exhibition – Images of other images. Interestingly enough, the handout pamphlet didn’t actually have any in-depth information about this section, or I might have taken an incomplete one. Can you provide a sketch of what is depicted here and the main ideas behind these artworks, and how it all fits into the concept of the Digital Dark Age?

AT: Overall, I think the concept of the exhibition is very philosophically provocative, and I don’t think we as artists provide a solution to it. It’s a provocative idea to compare the current moment to the dark ages, but there are elements that I can agree with, for example, when talking about preserving digital objects. The way we do it is very ephemeral – the LTO (Linear Tape-Open) tape that is also displayed in the exhibition is very fragile and needs to be changed or renewed every couple of years, but it’s the standard method for long-term data preservation.

About Images of other images – we were talking with Anete Skuja about making an intervention to the permanent collection of the Latvian Museum of Photography when we started work on The Shadow of Materiality. I thought about what I could add to the collection, so I decided to do another work talking about smartphone photography. You rarely see digital cameras in museums, so I wanted to bring it in this context and see how it works with other objects in the museum.

I started to look at smartphone camera reviews on ‘DxOMark’[2], and it was very interesting to see that many smartphone cameras have scores higher than 100. In these reviews they are using two methods: firstly, they evaluate the technical capabilities of the smartphone cameras by utilizing the same tools used for professional camera equipment testing. Secondly, they analyze the software that the smartphones use to simulate professional cameras and how well they do it. The technical side of the cameras isn’t that important anymore in the context of smartphone photography – the software is utilizing machine learning and the artificial intelligence is studying other images and using effects to create the photo.

I wanted to talk about AI taking over the process of capturing images. So, what I showcased was five images from these camera reviews. A motive that is very prominent is water – when you capture water, it’s easy to see how the AI manipulates the image and makes it almost hyperreal. The most substantial thing that can be seen is that these images kind of look like they’re made with watercolors – the AI calculates and approximates that a pixel should look a specific way, but sometimes it fails. The other thing that was interesting to me was the language that is used to describe this photography, so I made a poem from the review texts. It’s interesting how they describe the camera effects – it’s like language from video games or virtual reality programs, but now it’s part of the vocabulary of photography.

RB: I see, thank you! So, to sum up, this section tackles smartphone photography and shows the new problems that are coming in with the introduction of software in the process of capturing the image…

AT: Yes! I think that the smartphones are trying to replicate the look of a professional camera, but as the reviews are going past the 100 mark, they are approaching new territory, thus creating these hyperreal images. These cameras make images that function at their best on a social level and the technical part becomes secondary. It’s interesting to think how smartphone photography might look in ten years – I think it will be something completely different.

View from the exhibition “Digital Dark Age”. Riga Photography Biennial – NEXT 2021. Latvian Museum of Photography. Photo: Madara Gritāne

RB: And I suppose smartphone photography might fit into the scheme of Digital Dark Age in the sense that it’s accelerating hyperreality and straying away from the idea of authenticity because the camera is much more involved in creating an image.

AP: Which is okay, I think! But the issue is that these trends are provoked by capitalism and big companies, and that’s what is concerning to me. We are using the tools that they are giving us, but if you’re not aware of the tools that you’re using, then you’re a tool for a company.

I think photography education is becoming more and more important. The visual literacy of people is an interesting question right now – people are very aware of different effects and things that ten years ago they didn’t think about because professional photographers were the only ones doing it.

RB: I had another question – some of your artworks, and Images of other images in particular, made me think of the ideas of Hito Steyerl in her essay ‘In defense of the poor image’. She provides a fascinating overview of the social purpose of bad quality, low resolution images that circulate the internet – I suppose we could also extend this to memes as a way people communicate. Since you have studied the phenomena of social media images, maybe you have an opinion whether any of that is worth preserving and archiving and why?

AT: It definitely is – it’s human behavior. If we’re talking about state archives and trying to capture our era, I’m looking into how we could archive social media. To me, the image isn’t the most important part – it’s what we do with the image, what we comment on them, how we share them. We can easily archive an image, but how do we archive the social interactions that are a part of its provenance?

Many colleagues have asked me this as well – what is a poor image in the context of the archive? The poorest images are without descriptions. We can’t describe them. We have a sea of 100 kilobyte images, pixels that form something, but if you can’t distinguish it, it’s worthless. You can’t measure quality in pixels.

RB: I think a fascinating phenomenon is also early internet culture – some of it is preserved and archived on old websites. For example, somewhat recently I wrote an essay about emo music, and I think a very significant part of the information that the sociological studies on the topic used was found on these very de-centralized small forums and fan archives from the mid-2000’s. These are all interesting testimonies of living in the 21st century in general.

AT: And I think it’s becoming more and more relevant to study these kinds of things. When trying to analyze the current moment, in many ways we have to start looking 20 years back, not 50 years back.

RB: The way we tackle information is also changing every day because, obviously, the 21st century is a time when more and more of it is generated – or at least seemingly so. We are constantly leaving traces of our lives on the internet, and the pandemic has only accelerated the move to the digital in many aspects. What is your prediction – will we continue down this digital path, or are we returning to the material?

AT: It comes in waves – the urge to return to the material. In the context of the pandemic, it’s great that we could communicate digitally, but, for example, I was very happy to spend time with people in real life after the long isolation period. Trends come and go, but, unless there’s a huge catastrophe or something that turns off electricity, I don’t think we’re going to stop. We’ll go further and further in the digital. We are becoming more like cyborgs and some people are even biohacking themselves, but we all are more digital than we’ve ever been.

It’s very new for us, so that’s probably the reason why we’re asking these questions. We don’t want to fail. I think the exhibition name works with this idea as well – looking at the future and talking about the negative scenarios that might happen. These are the dangers that we need to be aware of, but it really depends on the social climate. Right now, there’s so much division, and I think that is the real danger for society. If we work through this division and evolve, then I think we’ll go deeper into the digital, but I don’t think it’s going to be a dark age.

RB: Let’s hope so! And what does the future look like for you?

AT: I’ve been asking myself the same question. I’m doing different projects where I’m appropriating more and more objects and showcasing them in an exhibition context. I’d like to go deeper into the topic of the future of digitized images and the representation of archival images, how representation is in the hands of different people and what the perception of an archived image provokes in us. Also, I’d like to contemplate the questions of what it means to appropriate and whether there are any boundaries. Of course, there are moral boundaries – as I said, you have to be careful when using objects with a terrible past –, but as we provide more and more representations of archival images to the public, it’s interesting to think what will happen to them, how they’ll resonate, how they can manipulate memories. For example, in the parish where I’m from – Toila – there was once a castle that was destroyed in the Second World War. People have a lot of nostalgic memories attached to it – it was a key building in the first Estonian independence period –, so I’m curious how the archival materials are provoking the memory of people. There are rumours that they want to rebuild it. I’d like to work on these topics and see where I can go, how I can evolve in the archival context, maybe start working on a thesis here.

[1] Benjamin W. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. 1935.

The interview was published in: http://www.punctummagazine.lv/