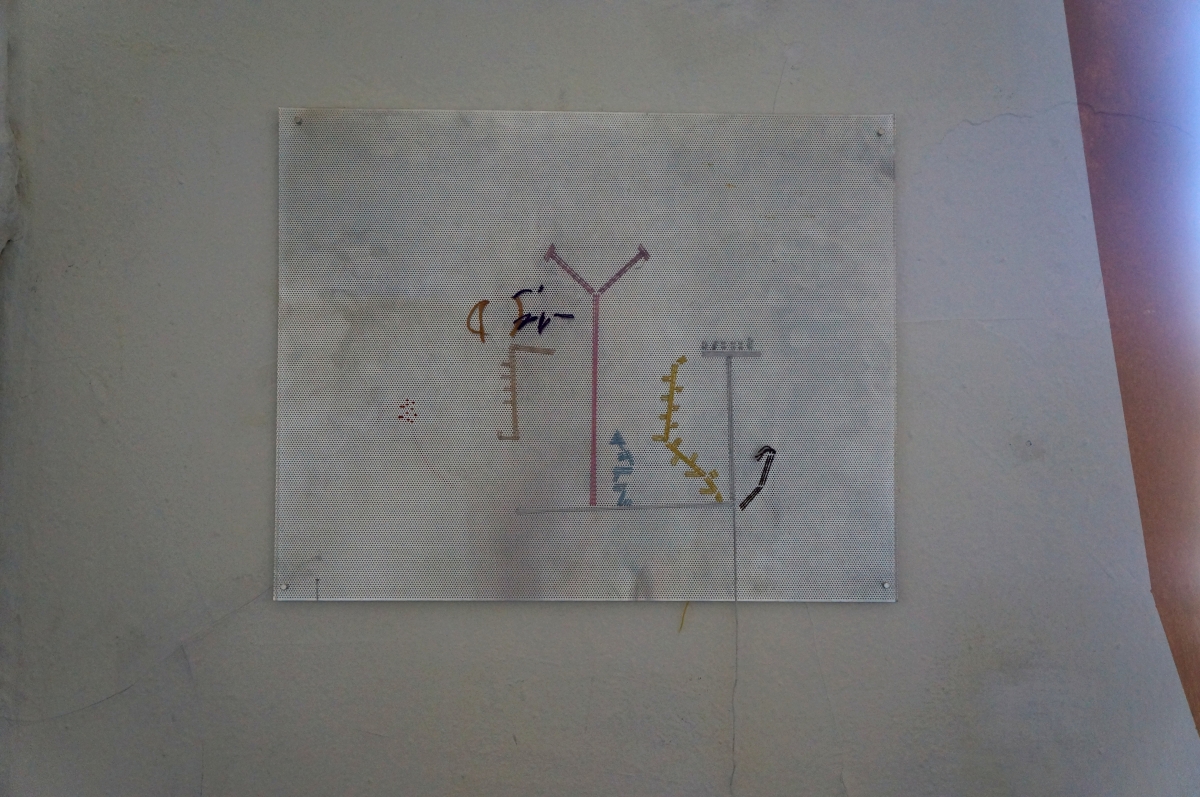

It is extremely refreshing, especially during this ubiquitous covid-induced dysthymia, to see the presence of an artist like Verena Issel in Klaipėda. In her new solo exhibition titled Wurzelpost (Ecosystem M) which opened at Si:said gallery on the 15th of August 2020, Issel presents uncanny juxtapositions of objects displaced from their usual referential structures and pragmatic environments. Chinese paper fans, fitness devices and human body parts all enter into dissonant “dialogues” and dysfunctional networks through a series of purposefully sloppy wall paintings (somewhat in the fashion of Philip Guston), ostentatiously perfunctory mixed-media collages and drawings, and a facetious installation that is placed in the gallery space like a well-timed joke.

Issel is a Berlin-based visual artist whose profile has been generating considerable attention in today’s art scene. Like many young artists who are becoming increasingly well versed in theory, she also knows her post-structuralists. By saying “knows her post-structuralists”, I do not mean an academic, scholarly type of knowledge. That type of knowledge, in Issel’s case, is rather irrelevant. However, this peculiar link between theory and practice, particularly in Issel’s instance, and in the context of visual art in general is what I would like to centre the rest of this review on and further elaborate. What got me thinking about their relationship in preparation for my review were a couple of statements I found in Issel’s description of her exhibition. In particular, I was prompted to thinking about the theory-practice connection after reading a sardonic statement (which seemed to reference philosophy of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari), which Issel had abruptly used to end her description, saying: “Rhizomes say Hi./We are system”.

But first let me begin with a little detour. In 1992, when the University of Cambridge, England, was considering awarding philosopher Jacques Derrida with an honorary degree, a number of analytical philosophers (including various prominent philosophers like Willard van Orman Quine) issued a letter, drafted by professor of philosophy Barry C. Smith. In it, they pressed the University of Cambridge not to bestow Derrida with the honorary degree, making a key claim that while Derrida’s writings did “indeed bear some of the marks of writings in that discipline [of philosophy], [t]heir influence, however, ha[d] been to a striking degree almost entirely in fields outside philosophy – in departments of film studies, for example, or of French and English literature”.[1] They challenged the university based on the fact that if the influence of Derrida’s work had been significantly more prevalent in disciplines other than the discipline of philosophy, why was Cambridge considering him to be such a significant philosopher? The letter argued, for instance, that if the work of a physicist would similarly be found to exert most of its influence in disciplines other than physics, this should be enough on its own to make us doubt whether that said physicist was worthy of an honorary degree. But this argument, of course, only works if one concedes to the idea that philosophy has the same standards of objectivity as physics does. However, in contemporary philosophy, the idea of verification and objective truth has been increasingly jettisoned. Moreover, one could even insist that the worth of a particular philosopher’s contribution could be measured precisely by the degree to which their work gains traction outside of the confinements of academic philosophy.

What, then, should the methodological criterion of philosophy be? Deleuze, a thinker in whom Issel, like many other artists and writers, finds inspiration, has famously described the discipline of philosophy as one of creation or invention of concepts, while the purpose of philosophical concepts themselves should be, according to him, understood not so much in terms of objectivity or truth value, but simply in terms of their use. Deleuze himself described the concepts that he and his colleague Guattari had invented as a sort of conceptual toolbox for anyone to use as they saw fit. For example, the worth of their concepts such as the “body without organs” and the “rhizome” could be assessed based on pragmatic, rather than purely theoretical, criteria.

One could argue that the world of art (as well as the world of political activism) serves as the most fertile ground for testing certain philosophical concepts. As a student of philosophy or an academic, when one brings up concepts like the “body without organs” or “rhizome”, one can often be ridiculed, even by sympathetic colleagues. Even Deleuzians themselves often exhibit a considerable amount of bad faith in these concepts. In my experience, artists are perhaps the only people who utilise such concepts with utmost sincerity and without any embarrassment.

Artists drawing on philosophical concepts are often, however, reproached for not fully grasping their significance, for taking them out of context and therefore for misapplying them. But, as I have suggested earlier on in this text, artists do not need to grasp the theoretical subtleties of philosophical concepts. If they find a particular concept useful, then that is good enough. Here, it’s important to remember that the reason Deleuze was critical of conceptual art was because he saw it drawing too heavily on theory. Conceptual art works “through the brain”, while the way any art should work, Deleuze insisted, is through our nervous system. Deleuze posited that it should employ affects rather than concepts. Nonetheless, I would argue that there is an important difference between the ways, for example, some members of the conceptualist Art and Language movement have used philosophy, and how artists like Issel have utilised it. One could say that someone like the American conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth sought to articulate Alfred J. Ayer’s and Ludwig Wittgenstein’s theories about language through visual means. Visual artists like Issel, on the other hand, do not seem to care about communicating any information through their art. I believe Issel, like many of her colleagues utilising concepts borrowed from post-structuralism, is employing them precisely so that they have an affective bearing on us. We are, I suggest, invited not so much to reflect on the work of art and to interpret its meaning, as to welcome its effects upon our senses and allowing them to displace certain perceptual clichés with which we operate in our mundane encounters. The primary function of a concept, as employed by artists such as Issel, would thus be to always render the affect more precise and poignant.

In returning back to Issel’s statement “Rhizomes say Hi./We are system”, the notion of the rhizome has not only become a fairly common currency within the fields of humanities and visual studies but has also permeated meme culture and discourse around the Internet so much so that it does not require too much of an introduction. That said, it would still be beneficial to briefly remind ourselves of what a rhizome is. In general terms, it could be described as an ontological system governed by several important principles: 1) connection; 2) heterogeneity, such that a rhizome always establishes connections between heterogeneous phenomena (language, power, political struggles and art); 3) multiplicity, through which these heterogeneous phenomena connect, calling into question the distinction(s) between one (unity) and many (pseudo-multiplicity); 4) asignifying rupture, lastly the principle that is capable of introducing breaks within the established systems of signification.

I definitely found Issel to employ at least the principles of connection, heterogeneity and asignifying rupture, whereby objects belonging to heterogeneous systems of reference and seemingly incompatible pragmatic environments have been brought together and made to communicate in ways that evade recognisable modes of signification. Again, Issel is not “illustrating” the concept of rhizome. Neither should anyone try to formally analyse her work in trying to see if her art “corresponds” to the concept of rhizome. This is not a matter of “applying” theory to art. What matters is whether the conceptual tool kit is employed by the artist in a productive manner. The success or failure of the employment of a concept such as “rhizome”, I argue, here should be decided on a purely perceptual and affective level. The questions that the visitors to Issel’s exhibition should be asking are the following: do the rhizomatic connections that Issel has attempted to forge between different and seemingly incompatible systems of reference actually work? That is, do they successfully introduce ruptures into our schemes of signification and, more importantly, into our stratified perceptual fields? If so, do these ruptures allow us to follow the aesthetic “line of flight” and thus to shake off, if briefly, our perceptual clichés? Moreover, are these ruptures more than momentary empty cracks in our horizons? Can they be taken as fecund “distorters” that would allow us to leave the gallery space feeling enriched with a novel, albeit highly subtle and tacit, perceptual disposition to our daily encounters? Can one feel the rhizomes say hi?

Verena Issel’s exhibition Wurzelpost (Ecosystem M) is open until the 25th of September 2020 at Si:said gallery, Daržų st. 18, Klaipėda, Lithuania.

[1] http://ontology.buffalo.edu/smith/varia/Derrida_Letter.htm

Photography: Rolandas Marčius