‘We postpone the unbreathable darkness that weighs us down.’[1] As Dénes Farkas is not the original owner of the memories exhibited, it is a viewer’s gaze we are offered: the viewers gaze at a viewer. We are gazing through Dénes’ eyes at this horrifying yet desperately beautiful fresco called life. It is a trap, because there is no exit through the (Banksy’s) gift-shop. We are the laboratory rats, chased into the tunnels of the mad experiment; and nevertheless, we have tried all the combinations, nothing seems to be right; but frankly, we cannot quit. Unless it’s ‘game over’. For ever.

‘We postpone the unbreathable darkness that weighs us down.’[1] As Dénes Farkas is not the original owner of the memories exhibited, it is a viewer’s gaze we are offered: the viewers gaze at a viewer. We are gazing through Dénes’ eyes at this horrifying yet desperately beautiful fresco called life. It is a trap, because there is no exit through the (Banksy’s) gift-shop. We are the laboratory rats, chased into the tunnels of the mad experiment; and nevertheless, we have tried all the combinations, nothing seems to be right; but frankly, we cannot quit. Unless it’s ‘game over’. For ever.

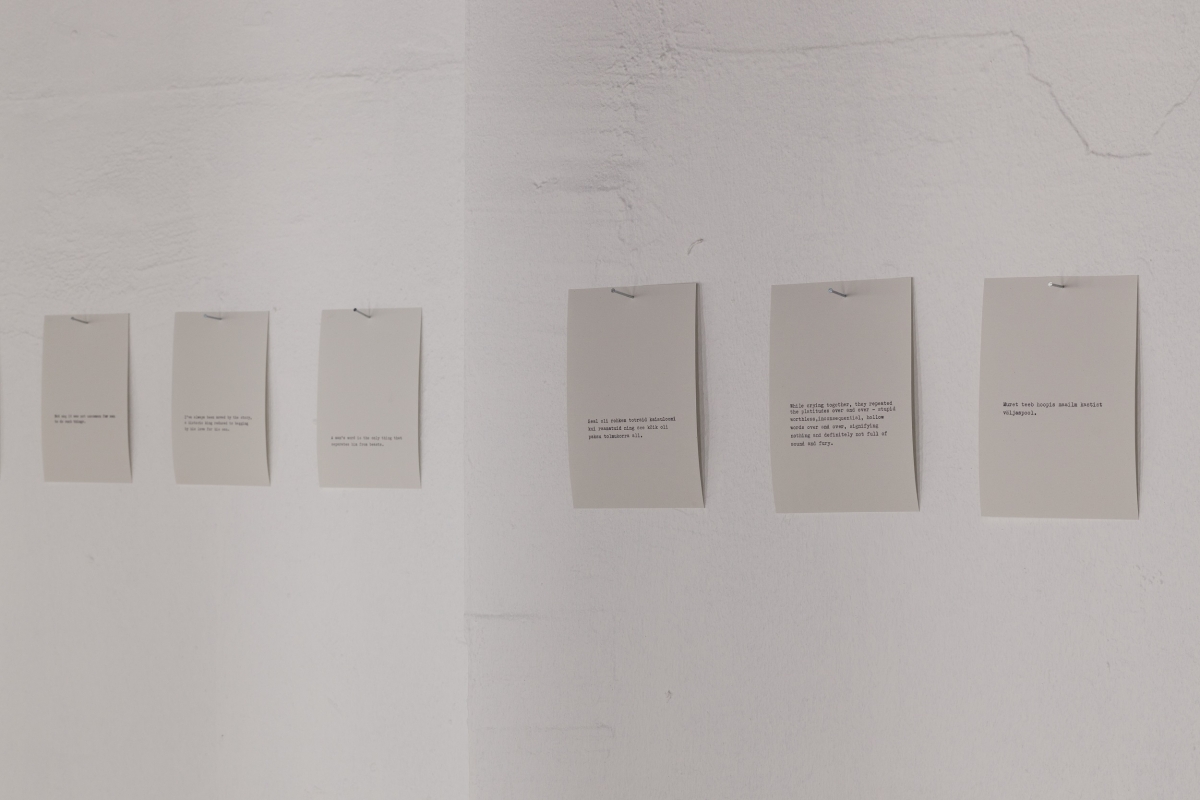

Dénes Farkas’ solo exhibition How-to-calm-yourself-after-seeing-a-dead-body Techniques focuses on every day, not from society’s abstract perspective, but on a very personal level. Dénes focuses on the importance of unconscious motives (wishes and desires) and conflicts in determining human behaviour. At the centre of his artistic interests stands the nature of violence. Frankly, it is not the violence of a dead body you may see on the streets in a war zone, it is (self)violence against the self-consciousness and the soul. The body Farkas is talking about is our own dead body. He is making remarks about society’s transparent but coherent violence against the wishes and dreams of a singular person, who tries to follow the rules of the game called society. He is speaking up about fear; but not the fear of death; he is gazing at the fear of life. The notes presented are the reflection of social predetermination in life. ‘I can’t force myself to believe that I’m in charge of my life,’[2] sighs someone who is not in a position of power. It is the sound of hopelessness.

There is a big question viewers are asked at the exhibition: Are our choices really so profoundly predetermined by society that they cannot be altered? In Eastern philosophy, the predetermined nature of life is sometimes referred to as the law of karma. Whatever happens is considered to be predetermined. There is no freedom. But Dénes is not talking about destiny, he is talking about a passive-aggressive attitude, which is not a psychological construct, but a sociologically produced mental and emotional unity. It is basically disorder. That attitude or disorder characterises a person, and determines how he is predisposed towards other people, institutions, hegemonic codes of behaviour, etc.

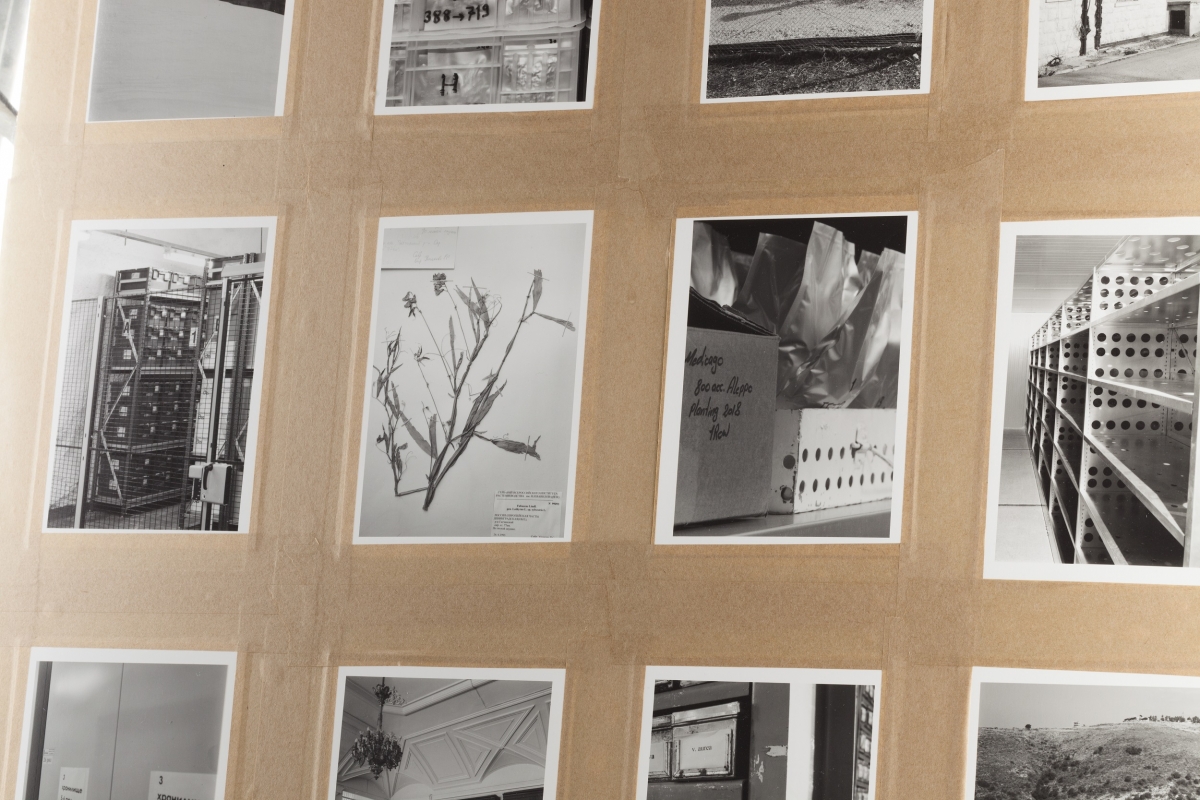

‘There doesn’t seem to be another potted plant in the apartment.’[3] Farkas’ visuals of fragile plants in pots with carefully labelled names on them seem to me isomorphic to human beings. ‘You not only inure yourself against fear, finding it bearable after a while and coming to terms with it, you also absorb it.’[4] Are we alive if we cannot live our lives according to our wishes, desires and dreams, when we are not able to move because of the rhapsody of fear we have absorbed, while our bodies are basically dead? And how to calm yourself after seeing so many dead bodies?!

‘The fact that my eyes could see, the voluptuousness of seeing, that my heart beat, the joy of having a body.’[5] Living bodies do not represent any value to society: they are not reliable and obedient citizens, members of society, the community, the family, the workforce … ‘What is a necessary human?’[6] In fact, society does not need living bodies. This is against the rules. And that is the reason we are not expected to step out of our pots and boxes. We just have to act (or not act) according to the rule book, and of course remain calm while we see other dead bodies. ‘We rarely consider that we’re also formed by the decisions that we didn’t make, by events that could have happened but didn’t, or by our lack of choices, for that matter.’[7] But we might as well turn a blind eye and persuade ourselves to believe that we are truly free individuals: ‘There is none more conformist than one who flaunts his individuality.’[8] Aren’t most of us conformists? At least on certain conditions or on reaching a certain point in life. According to the urban dictionary, a nonconformist is a person who does not conform to the trends of the average person. A true nonconformist does what he wants to do, and not what other people want him to do. So even the dictionary knows that there is an average person, and he is a conformist. ‘There are things I just won’t do, as much as I want to, if I intend to live decently with myself afterwards.’[9] I think this sentence must definitely be wrong, because here must be: within a society filled with conformist stereotypes.

As I see this, Dénes Farkas has brought to his audience the individual’s attempt to avoid distressing thoughts and feelings, which can lead to a variety of actions, some of which are very subtle and difficult to recognise. In psychodynamic theory, this avoidance is termed defence and resistance. ‘I stand in the dark and the dark, amid my wasted life, not knowing what to do, unable to make any decision, and weep. I close my eyes and wish to be transported to another dimension.’[10] How-to-calm-yourself-after-seeing-a-dead-body Techniques somehow leads my thoughts towards a lethal game called Blue Whale that involves eliminating ‘those who do not represent any value to society’.[11]

______________

Dénes Farkas’ personal exhibition How-to-calm-yourself-after-seeing-a-dead-body Techniques is on from 22 April to 4 June 2017 at the Contemporary Art Museum of Estonia (EKKM). Curator: Ingrid Ruudi.

Photography: Contemporary Art Museum of Estonia (EKKM)

[1] The exhibition leaflet.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.