The 18th edition of the Venice Architecture Biennale, The Laboratory of the Future, probably saw the least amount of ‘architectural’ exhibits in the event’s history. Immersively laid out by Ghanaian-Scottish curator Lesley Lokko at the Arsenale, the Giardini and Forte Marghera, the biennale offers more art than architecture, more questions than solutions.

What about the Baltic pavilions, only one of which is at Arsenale? When I find myself missing the utopian vision of Baltic unity from the biennale, I find comfort in remembering the 15th edition. Feeding the narrative that ‘we can also collaborate like the Nordics’, the collective effort of the Baltic architects Kārlis Bērziņš, Jurga Daubaraitė, Petras Išora, Ona Lozuraitytė, Niklāvs Paegle, Dagnija Smilga, Johan Tali, Laila Zariņa and Jonas Žukauskas to do the seemingly impossible—curate and create the first common Baltic pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2016—offered a way to rethink the Anthropocene inside perhaps one the most Baltic-looking buildings in Venice: Palasport ‘Giobatta Gianquinto’ (Palasport Arsenale), a brutalist sports hall actively used by the Venetian community for sports activities since the 1970s, designed by Enrichetto Capuzzo.

This year, the Baltic pavilions chose to act independently, each with a different approach, although what unites them is the focus on engagement and immersion, sometimes with a subtle nod and wink.

The most practical in its subject matter is the Estonian pavilion, presenting a plain flat. Their ‘flat-pavilion’, a sort-of curated apartment near the exit to Arsenale, has the somewhat invigorating title Home Stage, offering a much-needed, introspective look at the harsh reality of the Estonian real estate market. What else does one need in Venice, if not a curated apartment? Of course, similar undercurrents run in Latvia and Lithuania, it’s just that nobody talks about it. The curators of the pavilion, Aet Ader, Arvi Anderson and Mari Möldre, highlight the current state of the Estonian property market as stemming from 30 years of ‘turbo neoliberalism’ following the collapse of the Soviet Union. In our conversation, they stressed that their main motivation came from thinking about ‘young people put into difficult situations without the chance to privatise government-built real estate through special deals, instead needing to handle the pressure of taking out a 30-year loan at high Euribor rates or face the challenges of the small and uncontrolled rental market.’

The Estonian pavilion team is comprised of Mari Hunt, Aet Ader, Karin Tõugu, Kadri Klementi, Katrin Koov, Nele Šverns, Mari Möldre, Arvi Anderson, Kristian Taaksalu, Helmi Marie Langsepp and Jekaterina Zakilova. Their pavilion is a home and a stage at the same time. The performer who lives there addresses and highlights elements in the rooms, encouraging visitors to reflect on their homes and the politics of their countries.

Home Stage invites viewers to reconsider the values and priorities that shape our built environment. It challenges us to think about our homes as not only places of shelter and comfort but also assets, commodities and investments. It highlights the tension between the idealised image of a home as a sanctuary and the harsh reality of a market-driven economy that often treats housing as a speculative business.

Spatial interventions in the home space draw attention to keywords such as speculation, vacancy, depreciation, personal, unique and abode. Every object in this residential space, whether you view it as a home or a staged home, has been carefully considered and has a role to play. The main focus of the pavilion is on the wider challenges related to housing affordability. The curatorial team says that while Estonia has no governmental housing policy, it is urgent to consider what the status of a ‘home-owner’ means and what the process(es) of getting it entails.

Home Stage. Estonian Pavilion at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Kertin Vasser

Home Stage. Estonian Pavilion at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Kertin Vasser

Home Stage. Estonian Pavilion at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Kertin Vasser

Home Stage. Estonian Pavilion at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Kertin Vasser

Home Stage. Estonian Pavilion at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Kertin Vasser

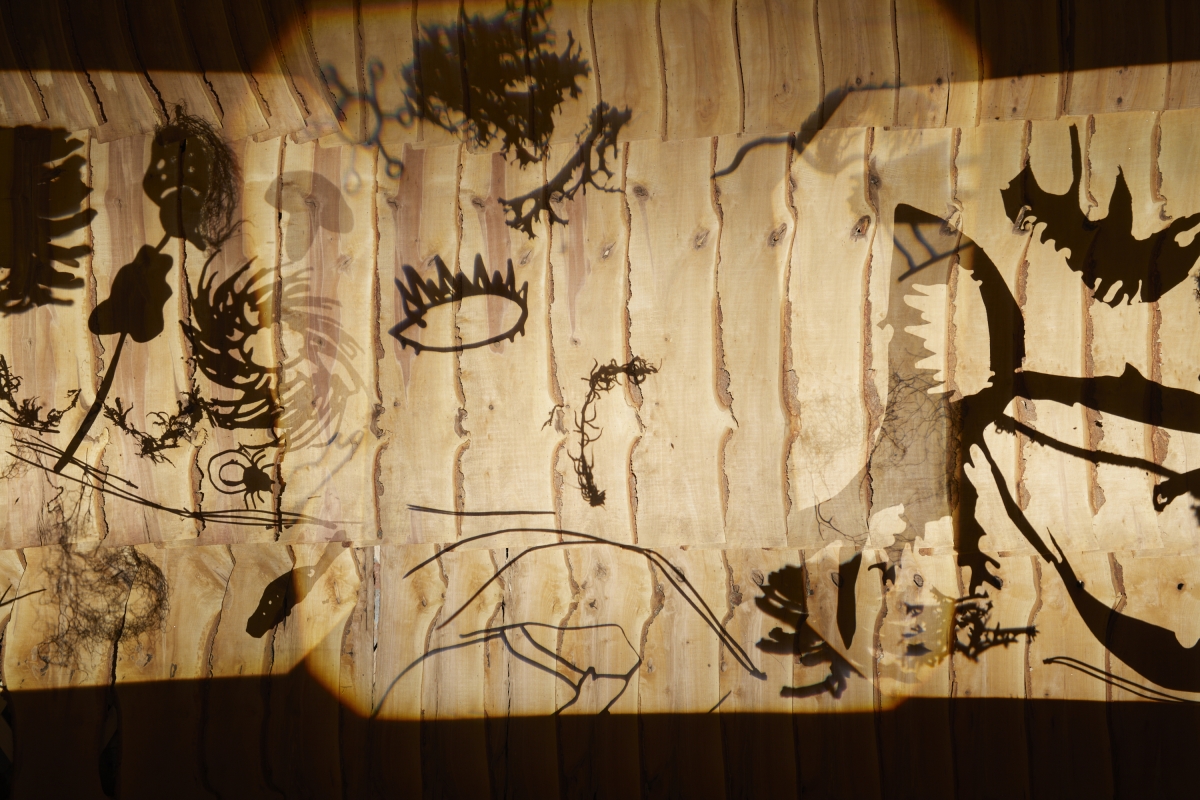

A similar layering is happening in Children’s Forest Pavilion, the Lithuanian pavilion curated by Jonas Žukauskas, Jurga Daubaraitė and Egija Inzule. At first glance, Lithuania’s pavilion constitutes an enchanting arboreal sanctuary and a veritable cornucopia of delights, meticulously curated around the joyous essence of childhood in the forest. However, beyond this overt focus, the pavilion manages to ingeniously bewitch the inner child residing within each one of us. Through its artful yet sophisticated staging, it orchestrates an immersive experience akin to meandering through the depths of a sylvan wonderland, beckoning inquisitive spirits to delve further into the hidden intricacies right within our natural surroundings, hitherto overlooked and awaiting our tender embrace.

While inviting visitors for a game in the forest, the Lithuanian pavilion is actually quite loaded and part of a complicated long-term research project raising very heavy questions. The Children’s Forest Pavilion is part of the Neringa Forest Architecture Project, which has been working on the topic of forests for three years at the Nida Art Colony of the Vilnius Academy of Fine Arts. The curators and creators of the project aim to increase forest ‘literacy’ (that is, human understanding and awareness of the processes taking place in the forest space) and engage visitors in questioning what our living spaces are made of, what infrastructure and decolonisation are, and what the role of architecture is in engaging visitors and audiences to explore difficult topics of how the current forest space is changing. These explorations allow viewers to see what will happen in the future, which looking at the current deforestation situation, seems quite dark.

Children’s Forest Pavilion. Lithuanian Pavilion at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Rasa Juškevičiūtė

Children’s Forest Pavilion. Lithuanian Pavilion at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Rasa Juškevičiūtė

Children’s Forest Pavilion. Lithuanian Pavilion at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Rasa Juškevičiūtė

Children’s Forest Pavilion. Lithuanian Pavilion at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Rasa Juškevičiūtė

Children’s Forest Pavilion. Lithuanian Pavilion at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Rasa Juškevičiūtė

Latvia stands out with its meta-theme, much less about widening the field of architecture and its meaning, instead choosing to recreate a repository of ideas from past pavilions, turning them into supermarket goods and doing away with the idea of originality. T/C Latvija (TCL) recycles ideas and activates archives, stimulating the viewer’s memory and even motor skills. Curated by Uldis Pētersons and designed by Ernests Cerbulis, Ints Mengelis, Toms Kampars and Karola Rubene, the Latvian pavilion has already garnered attention for its innovative and tongue-in-cheek approach.

Uldis Petersons explains that TCL is a shop at the Venice Architecture Biennale that showcases 506 unique products, representing all the countries featured in the past ten biennales. AI was used to create concise summaries of each ‘product’ and other AI tools, specifically the Photoleap AI Image Generator (Midjourney), assisted in designing visual images of the products. While Ulids appreciates the role of AI, he stresses the importance of the human touch.

Uldis notes that for the Latvian pavilion, TCL acts as a laboratory where every visitor becomes a researcher, exploring the products and making decisions. The voting system implemented in the pavilion aims to involve visitors in the architectural process, allowing them to select one of the historic pavilions from the biennale using balls which represent TCL currency.

The curator emphasises that this meta-pavilion is not solely focused on innovation. Instead, they view architecture as a fun and playful process, inviting visitors to reflect on the past 21 years of the biennale and evaluate the ideas presented over the years. Did all ideas remain at a theoretical level or have some materialised? Looking beyond the exhibition, the team hopes for active visitor involvement to gather data on the most popular products. The focus is on utilising existing creations rather than constantly producing and consuming new ideas. By choosing three TCL products, visitors can potentially generate new ideas without wasting time creating something entirely unique.

What united all three Baltic pavilions this year was the choice of the curators to create an intimate way of experiencing the installations. While part of a larger trend, this approach is necessary for the biennale’s topic of The Laboratory of the Future and the overall context of the biennale—to slow down and take a break from the fast and dense format of exhibitions and become truly engaged through entering someone’s private space, playing with parts of the forest, exploring its dark and hopeful secrets, or playing the lottery game of the AI-generated biennale archive.

After a visit to the Latvian shop of ideas, followed by a detour in the Lithuanian forest, visitors are asked to remove their shoes at the doorway of Estonia’s flat. At the forefront of the knowledge building that will be the key to the laboratory of the future is the relationship of the space, viewer and installation. The pavilion spaces become stages that create architecture capable of capturing the vague and temporary moment of learning through immersion.

T/C Latvija (TCL). Latvian Pavilion at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Toms Kampars

T/C Latvija (TCL). Latvian Pavilion at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Toms Kampars

T/C Latvija (TCL). Latvian Pavilion at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Toms Kampars

T/C Latvija (TCL). Latvian Pavilion at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Toms Kampars