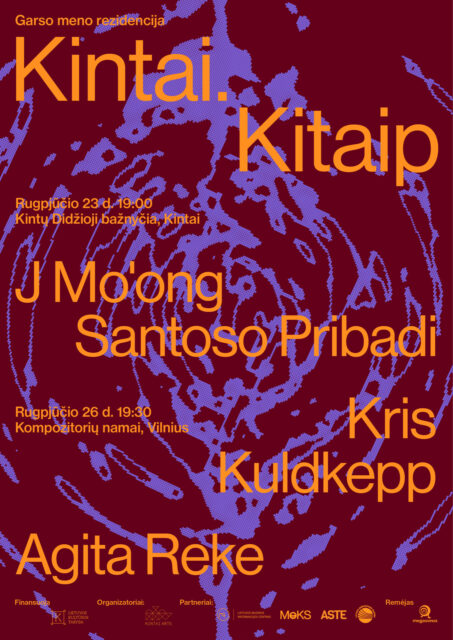

Laura Garbštienė (b. 1973) is an artist with controversial experience. After her textile studies at Vilnius Academy of Art, artist residencies abroad, and producing video works and performances, seven years ago she made her home in Šklėriai, a small village near Dzūkija National Park. There she raises sheep and spins. The remote village is now full of the energy and artistic experimentation that Laura brings and applies herself. In recent years, her work has turned towards nature, ecology, collaboration, consumerism, and expression that is not for the white walls of a gallery. Laura is a lifelong learner, who studies poisonous plants, spins and writes books. This interview covers all these topics, her recent exhibition at the Atletika gallery, and more.

Agnė Sadauskaitė: In October, your exhibition ‘Knife-Blades Slowly Synchronising’ was on at the Atletika gallery, a newly opened art space. Knife making, knife sharpening and wood carving workshops took place alongside it, in which attention was paid mostly to the process, and not the result. What ideas inspired your installation?

Laura Garbštienė: Atletika opened recently, and the exhibition was prepared quickly. The idea was born spontaneously. In the spring, I started studying carving in Varėna. This summer, a lot of artists started talking about the disappearing green spaces in Vilnius. For me, that was less relevant, as I live in the countryside, but these pieces came together as one idea. I thought that cut trees could be taken to the gallery, and Christmas tree-shaped carvings could be made out of them. The Atletika space then resembled a jungle, the lying tree branches and carvings resembled sadness. I wanted to clean up the rubbish that nobody needed. In the countryside, every movement is meaningful and sustainable, there are no unnecessary things or rubbish.

I also invited people to carve because there was a workshop going on, and carving is very simple. I believe anyone can do these things, sustainably and using only what is needed. It is also important that there was no specialist to teach carving. Technique was not the key element here. Specialisation of any kind can make us lose a lot. That’s why it was good for me to leave Vilnius, because then you get away from the same people, faces and exhibitions, and at the same time you get a deeper insight into how the world works. Although artists are very open, the contemporary art scene is extremely consumerist and competitive, the artist has to present a good collection to the gallery. Trying to think through processes goes beyond the traditional exhibition space for me, however. How do you represent yourself? I try to avoid traditional spaces; now I have no desire to put my exhibitions on walls.

I wanted to mount an exhibition in the woods, without artworks. It would only include people who had become pieces of art: people are rich in themselves, very creative. Therefore, this exhibition is my achievement. I did not bring any prepared pieces of art to Atletika. Volunteers collected the wooden branches, and I just said in which direction the exhibition should go. I enjoy acting without strict instructions, and observing what happens.

Laura Garbštienė. Knife-blades slowly synchronising. Exhibition at the Atletika gallery, 2019. Photo: Laurynas Skeisgiela

Laura Garbštienė. Knife-blades slowly synchronising. Exhibition at the Atletika gallery, 2019. Photo: Laurynas Skeisgiela

AS: Your previous works Unfinished Diploma (Nebaigtas diplomas) and Record (Įrašas) presented similar topics, the supremacy of the process over materiality, the relationship between performance and outcome. Why is the process much more important to you than the result?

LG: The process is more interesting. Now I realise that this is the way of creation, how it works, how it speaks. All the actors, not only the artwork and the spectator, but also ecology and the environment, must be taken into account when creating.

AS: The exhibition at Atletika asks how much a person actually needs excess consumption, assuming that the current scale of material desires and aspirations is irrationally expanded. Did moving out of Vilnius reduce your needs?

LG: People are greedy. I moved away because I felt the urge to grow plants, to have a garden. Fortunately, I chose a permanent place of residence, because only later did I realise that plants need constant care and attention. That’s how four years passed before I finally realised that I had not been creating art for long time. Then I thought I was missing something … Still, my needs have increased, but in different areas: the need to go to the forest for a walk, the need to do nothing, the need to not create things.

AS: You are the author of a socio-cultural project/initiative called ‘The Spinners’ (Verpėjos). How did you create this project?

LG: I wanted cooperation, activities, and a spinning wheel workshop. I invited several artists, and the first, very small symposium was held in the village of Margionys in Dzūkija. Other artists invited some more women, who found it amazing to learn how to spin. We did some more exploring, walked around the villages talking and interviewing people. Women in the villages were still spinning, remembering how their grandmothers had taught them, and what fun it was. Communication was one of the key activities, because we did not create an art product. Then I came up with the idea that we are spinners, networkers, who spin connections and communication. Later, the other artists went their own way.

We organised a presentation of the symposium at the Dzūkija National Park Visitor Centre in Marcinkonys, and later published our findings in the periodical Šalcinis. This publication is ethnographic, traditional, and at the same time oriented towards nature. Spinning on a spinning wheel seemed quite an ethnographic topic, but then I started to contradict that perception: everyone used to spin in the past, and there is no spinning craft. The area in the national park where I live is famous for its unspoilt villages, and there is often a desire to support, continue and encourage traditional activities. Nevertheless, both agriculture and crafts are a myth. What everyone really does is not crafts, but handicrafts.

AS: Your project ‘The Spinners’ resembled the installation Elektroninės sutartinės (Electronic Multipart Songs) at this year’s heritage event Heritas, where the movement of a spinning wheel is accompanied by electronic music. It was an attempt to modernise the old tradition, and to contrast the sounds of wooden wheels with modern music. Are you in favour of how traditions, rituals and the cultural heritage are presented nowadays?

LG: I have said quite strongly that I do not really like all parts of representation, and not everything is interesting. Crafts will never come back, because we cannot do things as slowly as we did a hundred years ago at a completely different modern speed, with the world flowing around us. We knew about Elektroninės sutartinės, and we had a little laugh, and that’s it. Popular cultural figures make souvenirs out of spinning wheels, but I cannot criticise it, because it’s very different to what I do. Their show and ours took place at the same time in different locations, but they were presented in the media as one event. It’s also interesting that these events are praised in Lithuania for their representation of ethnic culture. What is not ethnographic is that people just need yarn. It’s now a matter of wanting to do things as slowly as possible, rather than maintaining implicit traditions.

AS: What are your plans for ‘The Spinners’?

LG: ‘The Spinners’ has become a public institution, with which I organise activities. I would like to invite more artists to carry out projects with me, and I have leased a space for events at Marcinkonys railway station.

Last year, in 2018, I had a plan to organise the Spinners’ Orchestra. This is a separate project: the orchestra is formed every time in different places from different people. We invite people who want to learn how to spin and have their own spinning wheels to join the orchestra. It’s always the same: about fifteen people come, mostly women, all very happy and excited. They come from different backgrounds, usually no one knows how to spin, but they dream of it because they own a wheel inherited from their grandmother or another relative. It’s hard to learn: we study for two days, and on the second day we can usually spin the yarn. While learning how to spin, we listen to each other, and it’s a completely different kind of communication, like a ritual.

It’s known in advance that there will be a public appearance of the Spinners’ Orchestra at the end of the course. I was hoping to make sound recordings of a show and spinning wheels, but it’s complicated: it requires expensive hardware; spinners and spectator spaces resonate differently. All the wheels are very distinct, old, squeaky and rattling. It’s beautiful, too.

The art here is marginal, but the gathering itself, the performance of the orchestra, the formation of it and the community, turn into a body. Then you can talk about important topics, ecology, and wool that you can use without a commercial purpose, ritually. It takes time to spin a yarn. Only after half a year of using the spinning wheel can you slowly master it.

AS: Do you have a hope that people will learn to spin and make their own clothes?

LG: Yes, but that’s just an idea. I really don’t think everyone will start living in the woods, growing potatoes and buying nothing. Still, I realised it doesn’t matter; the most important thing here is the moment, the learning process and the slow way of thinking. Learning how to spin is like learning how to ride a bike: you’ll never forget it. Using a spinning wheel is secret knowledge, and carrying that knowledge is a small mission. It’s very beautiful to me.

Exhibition at Marcinkonys railway station

AS: Although you are, geographically, far away from the events and galleries of Vilnius, you create art in the place where you live, in unexpected and unsupervised spaces, in the forest, in Marcinkonys railway station.

LG: We made a gallery in the station waiting room. I once did a spinning wheel workshop, but did not put on an exhibition. We have also become a satellite town in Kaunas International Film Festival: we showed one film in Marcinkonys, and now we’ll have to look for possibilities to present films in the future.

We currently have an exhibition that was organised with the symposium participants: I wanted to tell an interesting story to the locals. The graphic artist Gražina Didelytė lived in the reserve, and created a series of works called ‘Skroblaus vingiai’ (The Bends of the Skroblus). We exhibited it for the first time in a public space. The artist lived in a very restricted area that has been designated a nature reserve, in the village of Rudnelė. There, in her backyard, she made her own gallery, exhibiting the work. For some time now, visitors have not been admitted to that area. It seemed interesting: how to read, how to understand a piece of art, when it is not available, not possible to reach?

AS: In the invitation to a spinning workshop you mention that this is not an attempt to romanticise the past, but to consider the problems of the present, the ecological situation. You have also published the book Kaip pasodinti mišką (How to Plant a Forest), a minimalist guide to growing a forest-garden, a city-garden, or a forest. You mentioned that you might introduce a new kind of meditation, raising sheep and using a spinning wheel. The exhibition at Atletika invites us to talk about consumerism. Are the topics of ecology, nature and minimalism becoming more relevant to you?

LG: It came to mind when I left Vilnius and started to project my mind less on myself. The distance from the city and art institutions as a form of structure raised questions about how the world works. In the past, it was important for me to understand where I am, what I’m doing, where I am in the world. Now I can look at it objectively; I have a wider view. Ecology, then, came not as a dialogue, but as an initiation of conversation. Now I wonder how to involve other people; for example, the emergence of the project ‘The Spinners’ seemed to me like an important social movement, because when you live in the country you start to think about what you can bring to the place, to its people. I feel I can make a difference, but I realise that it cannot be sudden and big. It’s more a series of small changes that inspire several people.

AS: At Galerija Vartai you presented a ‘bazaar’ called ‘Laikinas meno fondas’ (Temporary Art Foundation), where you brought your own raised/collected natural goods, such as jars of jam. ‘Gamtos pažinimo kambarys’ (Knowledge Room of Nature) is a collection of poisonous plants exhibited on the pages of a prestigious art event, the catalogue of the 54th Venice Biennale. Art is often mystified and made sacred, while you turn exhibits into local Lithuanian versions of Marcel Duchamp’s ready-made objects, which could be created by country people, while a prestigious catalogue becomes valuable just for how many plants could be represented on its pages. What was the purpose of these performances?

LG: It all took place in a commercial gallery, where selling a jar of jam seemed a good joke to me. It was also important because of the process itself: I’m not creating pieces of art, but making jam, which is a simple presentation of an idea.

I was invited to be included in the Venice Biennale catalogue, but I declined, as I did not want to be represented. I wanted to attend the Biennale myself. The idea of a catalogue and poisonous plants came spontaneously, for the whole system could be depicted as poison. These catalogues were free, so they were not needed any more, and were collecting dust somewhere in the corner. For me, it was a wasteful product, so reusing it for the herbarium was a sustainable idea. The poisonous plants that were in the gallery were simple plants that had poisonous substances, like potatoes and tomatoes, but there were few that are deadly to man. During the preparation of the exhibition, I enjoyed the cognitive process the most, preparing intensely, reading about plants, writing out chemical formulas. It was a beautiful new area, with its own systems, groups and Latin names.

These are my reflections on the project, but it hasn’t been officially declared. Over time, things appear somewhat different; then I said that I did not want to prepare an exhibition, I would not make films, and you would not see me in them, because most of my works are performative. Everyone was thinking that my exhibition would not happen, so it was a kind of protest. I started to think how to avoid having the work put on the walls of a gallery. I wanted to find other ways.

The Bends of the Skroblus

AS: Laura, you have a sensitive outlook on the world. I feel a gentle search for meaning in the environment, a rejection of standards and templates, along with mild irony and criticism of the art world. I really like it that you do not mystify art.

LG: Mystification reminds me of packaging: it’s also a way of presenting a thing. It was always more important to me to state the idea, and form followed and was less important. Now my earlier video works seem quite amateurish. I realise I could have done them more professionally. On the other hand, I really enjoy amateurism.

AS: What metamorphoses await you after living in the forest?

LG: I don’t know yet. Maybe more artists will come, maybe we’ll have a not very formal artists’ residence, and then I’ll move away somewhere after some time.

AS: Mysteries arise when you talk about the future though.

LG: I cannot honestly talk about things I do not know. I like to do things I haven’t tried, and I dislike routine; but living with animals has changed me a lot, I have to rear them, and I have immersed myself in the ground too. Only now do I understand how much animals matter. They are closer to nature, and have more knowledge than humans think. If I was raising a horse or a cow, instead of sheep, I would probably have grown into the ground.

Laura Garbštienė. Knife-blades slowly synchronising. Exhibition at the Atletika gallery, 2019. Photo: Laurynas Skeisgiela