Art Vilnius 2017, Galerija Menu Tiltas, Vilnius. From personal Rūta Jusionyte archive

Rūta Jusionytė (b. 1978) is a painter and sculptor. We started our conversation with the artist in her studio in Paris, surrounded by the cheerful buzz of children, where the sounds of the French and Lithuanian languages are common. Born in Klaipėda, she started her relationship with art at an early age, when attending the Eduardas Balsys School of Visual Arts. She continued studying in her home town at the Visual Design Academy, and later at Vilnius Academy of Art in 1998-2000. This educational period could be defined as the formation of Rūta’s ideas on art, while her main artistic career started and developed in Paris, France, where she moved just after finishing her studies in Lithuania. The work of the young woman was noticed and appreciated: in 2016, she was awarded the prestigious 2015 Georges Coulon Prize of the Academy of Fine Arts at the University of France for figurative sculpture. Rūta is a productive artist, exhibiting since 2003, mainly in France, Switzerland, Germany and Belgium. Nevertheless, her creative relationship with the Lithuanian art scene is getting tighter as well. She represents many social roles: a woman artist, mother and human-individual. Her paintings question humanity, nature, and their interconnection; her sculptures represent different phases and encounters in the life of an individual. Communication with the viewer is started and continued in symbols, elements and primitive forms, and is never a monologue.

Rūta, you studied in Lithuania, lived in Klaipėda and Vilnius, and later Paris became the city where you live and create. Have your inspirations changed during this geographical transition?

The creative process invites new ideas, inspired by experience of life, the people around you, mythology, old stories, and contemporary events. I arrived in France just after I graduated. At the time, my understanding of what I was doing was very ordinary and childish, so French and Lithuanian cultures mixed in my art. Now, even more broadly, it is a mixture of Ancient art, Egyptian art, the Impressionists, the Expressionists, Francisco Goya, Diego Velazquez, Caravaggio, Emil Nolde, Munch, Paula Becker, Germain Richier, Marino Marini, Bazelitz, Immendorf, Gerard Garouste, Marc Luperz, John Burgert, Antanas Gudaitis, Cukermanas, Stasys Eidrigevičius, Marc Petit, Jean Rustin, Paul Rebeyrolle, Lydie Arickx, Serge Labegore and others. My style was formed by these influences, and by my own knowledge and maturity.

Although Germaine Richier states that we all question the same repetitive topics throughout our lives, I hope that my style and themes will continue changing, because there is nothing more terrible than closing in on one idea and being repetitive. Simplicity and clarity are the values that to me make a piece of work lasting and understandable to everyone.

You are associated with the contemporary French Expressionists. Did this bond form naturally, or was attribution ‘from above’?

It happened naturally, and was consistent with my own work, because it is based on emotion. Exhibitions and galleries have integrated me into this artistic movement. I am not one of those artists who ‘scream’ crudely with colours. My work has recently merged (or levelled out), and I can distinguish two branches, Symbolic Romanticism and Contemporary Expressionism. The Expressionist is not pushed into rigid frameworks. The art critic Christian Noorbergen speaks of the Expressionist as an intellectual artist who has studied and learned, and in his artwork tries to reject aesthetic, intellectual facades, and look deeper, pulling out creative elements with the determination to do so. The emotional basis manifests itself right there: the artist enters the creative atmosphere when it may seem that he does not think, but is accompanied only by his robe or sculpture. At the same time, there is an energetic relationship with what he creates and what comes from within. In most cases, it is strange when an artist feels within his work: he does not know what exactly, but he feels. It could be said that this is the chaos of emotion, something that cannot be explained to the artist himself in the creative process, but only later, when it is finished. Still, while developing, in the process, it is just the determination, daring to drop all the intellectual and moral hurdles, and doing what looks right. It comes from inside.

My initial creative process is often theoretical. First, I have to fill myself with information, new ideas, theories and topics. I read and search for it. When I finish with the theoretical part, I then put this information into the subconscious level when I am in the studio. I try not to theorise about the particular topic any longer, and let surprises occur that bring new and already accumulated things. This happens without much consideration, intuitively. When I finish a work, I can think about it: what happened in the process, did I advance further, or did I just portray what I had already learnt and summed up?

Rūta Jusionytė. Face à face huile sur toile. 162 x 114 cm.

Could this be called an impulse?

It is pure inner emotional communication. The term ‘impulse’ is suitable for performances, but not in my case.

In 2017, you participated in the international exhibition ‘Contemporary French Expressionism and not Only’ in Kaunas. One of the announcements stated that ‘Rush, grotesque, hell, black, red, brutality, imbalance, fall: all this could be expressed in the emotions and the Expressionists are doing so.’ You mentioned that your own work is not only black and red; it does not necessarily mean an imbalance or a downturn. How would you describe modern French Expressionism?

It would be very easy to say that there are only black and red, related to negative emotions: this is a simple portrayal of art. Expressionism is not based on political foundations, or created to oppose. The Expressionist dares to go deeper, avoiding making allegations, and chooses to raise questions. They try to express themselves in pure colour, strong lines and contrasts, because all that is an emotion that the artist is not afraid of and dares to play with. Emotions are very different, they can be based on courage, love, or soft feelings; but at the same time, it is a reflection on the topics of birth and death. Often in these cases, the Expressionist goes deeply, and asks where and what is the true meaning of life between the beginning and the end, the inner process of life. For me, the topics are the same, but they pass through my own experience.

Meaning that the source of inspiration, the basis for creativity, is your own experience?

There are three things. My own existence as a human being, an individual in modern society. The other is national-cultural: we naturally have a lot of expressiveness in our country, with contrasting history regarding the many wars and disasters, a contrasting climate, when winters are cold and summers are warm, we have many bright days, or no sun at all. People can be very friendly and open, but we can also be cold and closed. The third prism is personal, and depends on the family, maturity, and what formed the personal sensitivity. With regard to the artistic expression of each artist, these things are manifested in different ways: one depicts only landscapes, others choose people, and so on. Talking about expression, artists such as Emil Nolde, Paul Rebeyrolle, Zoran Mušich, Willem de Kooning, Lydie Arickx, Arvydas Saltenis and Antanas Gudaitis are connected in the sense of depth, sensuality, a strong plot, the endless pulsation of life, and the perception and feeling of life irrespective of the national context. In order for this to happen, all these three things have to be connected, and cannot be dealt with separately.

Which of these dimensions matters most?

Currently, the most interesting is personal, because it can be viewed through the general experience of humankind. I am particularly interested in Ancient Greece. They thought about what a ‘good life’ (in French la vie bonne) is. This is what the philosophers Judith Butler (Qu’est-ce qu’une vie bonne) and Luc Ferry write about. A good life is not in a hedonistic sense, but with respect to personal qualities. In this case, it is more interesting to consider not only questions of birth and death in a philosophical sense, but how the life of man as an individual is happening today, how he lives, feels, creates, and what he is interested in. We do not live as a group in occidental society (in French société occipale), we do not think as a group of citizens, but as individuals. My reflections relate to the ‘good life’ of the Ancient Greeks, since man lives in the present today. We live once: in fact, we can assume that we are not responsible for what will happen after us, and we can live for this day. It is consumerism, joy, pleasure, and ‘after us, and the flood’. However, what does ‘live well’ mean? A man does not live alone, he always relates to others, and other people’s relationships with his family, parents, children, friends, other peoples, and the whole world. This whole creates welfare with others. As a person behaves well with others, so it will be good for him to live. The issue of man as an individual in today’s society is closely associated with this.

Another relevant topic is the question of woman. Women are free, they can work and vote. In France, for example, after 1968, women won the freedom to be independent of the husband and the father. So, the situation of a woman and a man has already been discussed, not stating that there are no other issues to fight for. This foundation, woman and man and their relationship, arises in my work, in sculptures or paintings. It could represent the issue of equality, or questions put to each other, who you are, how I will interact with you, what we will give each other. The psychologist Carl Gustav Jung states that we have femininity and masculinity (anima and animus) in ourselves, and over the years, masculinity grows stronger in women, and vice versa. In my work, there is a reflection on two sides in one person, for example, in the sculpture Anima-Animus.

Rūta Jusionytė. La fille et le lapin dans une barque

Topics that interfere and are presented in your work reflect and question society, dilemmas in relationships, and the existence of individuals. What symbols and metaphors are the basis for converting these ideas into artworks?

In my work, a common symbol is the animalistic portrayal of a human (animalité, bestialité) based on old European tales, especially Lithuanian, Greek myths, and the fables of La Fontaine. In most cases, the depiction is as follows: the wolf is dumb and cruel, the fox is wise, the hare is fast and good, the bear is strong and threatening. All these beasts either protected the person or warned of a threat, and at the same time portrayed the human character, whether a person is brave, strong, fearful, perhaps even naive, determined or silly. There are many questions that do not have specific answers or clear boundaries; it may be that way, but it may be somewhat different. In the case of the bear, he was the king of the forests during the pagan period, the supreme animal god. The Catholic Church, which began to convert pagans, in many ways belittled the respect for the bear; for example, the bear was forced to dance in front of kings. In order to do so, bears’ feet would be burnt from the bottom since the early days (in this way, the bear would move the legs as he was dancing). Still, the symbol of the bear remains a symbol of strength and grievance, but at the same time intelligence and majesty. This is an example of an archetype that has passed from one generation to another, without knowing where it is from, or why. The same happened with the Minotaur, the Centaur, Pegasus, the Turtle, the bunny, and the wolf, and also the elements, water, earth and air, and even necessities closer to the person, the home, fire, heat, air and light. Questions in my paintings are related to that, whether light is artificial or natural, does the person live in a city, an apartment or in nature? Does nature surround a person, how is it organised, how much does a person know about animals? For these reasons, my paintings sometimes reflect opposition: the green of nature is represented in an interior, and only a little piece of greenery is seen through windows. In a garden or a field, a garland, a representation of artificial, electric light, sometimes represents an electric or false relationship among people.

At the centre of your sculptures and paintings, there is a human representation, mostly with the feminine side emphasised. In the sculptures, women are embodied in their original form, when men are often reflected by anthropomorphic expression. Does the creative core become a woman, or is it a reflection of humanity and society as a whole, when sexuality takes second place?

In my work, there were various periods of Motherhood (woman-child) and Humanism (human-individual). Ten years ago, I focused on the topic of life and death, to which I am now returning, emphasising individualism versus universality. I agree that in 2016 and 2017, I concentrated on women’s issues (a woman and her relationship with the public, between a woman and a man in a couple), and today this question seems to be resolved. Current processes in the workshop are moving towards the reflection of the individual’s indifference, commonality, and the human as a unit, but the relationship between femininity-masculinity, the relationship with society, while incorporating reflection on the idea of what is a ‘good life’, persists. My current work is in this particular context.

Art becomes an important tool in questioning the emerging or emerged social roles. Do women’s roles, women-men relationships, human relations with the world, in your art become a search for controversy, a reflection, or a statement?

It is definitely not a statement. This is an open approach, where several issues can be raised in one. My work is debatable, even a partnership; it is a desire to communicate with the viewer.

Have you ever tried to give clearer implications with stricter limits?

I help a person to see; that is why I am a painter. The painter gets information about the surroundings by observing life and the world, using symbols, historical elements and metaphors, and conveying himself through what could be relevant to others. The locomotive is me, and I do not make final decisions, but I provide the elements through which people can see. The psychologist Jacques Lacan also highlighted three closely related elements (noeud borroméen, boromen rings): reality, fantasy, symbolism. They are all involved in the creative process. There can be no reality without imagination, or without symbolism.

Traditional gender roles seem to be levelling out, but each of us represents a number of social roles. You could be described as a person, an artist, a Lithuanian, a mother. Has becoming a Woman-Mother brought you new ideas?

The painter Paula Becker started to depict the woman and child before she gave birth; in my case, this started only with motherhood. Then the questions arose: what is it like being a mother, what does motherhood mean to me and to others? However, this topic is episodic, and is not the basis of my work, but it is very interesting. What is the woman in relation to her child in today’s society: a mother, a wife, a grandmother? Another relationship is the woman-child, where the woman does not necessarily reflect protection, but through the child the mother learns about herself, and experiences the world.

You have held personal exhibitions, and participated in group shows and art fairs. In 2016 alone, you held six solo exhibitions. It is a challenging activity, so what is your work routine: bursts of energy or thought-out projects?

I go to the workshop every day, but these are creative cycles. After each exhibition, there is a feeling of emptiness: I give my whole life to the exhibition. Then a week, a few days, or sometimes even a month has to pass while my energy returns. During the creative cycle, I do not count time or rhythm: I work in the mornings, at weekends, a whole month … until the victory, until it is done. For example, last year in Switzerland, I had a personal exhibition where all the works shown were created especially for it. I was seeking integrity by choosing the theme Undine (Mermaid) and everything that is related to water. Clay is my main material, and in French ‘clay’ (terra cotta) also means earth. In the exhibition, I linked two elements, water and earth. The mermaid, though, is in the interaction between the two elements, and comes from the water to the earth.

All in all, what is the greatest joy in your creation?

What awaits me in the future!

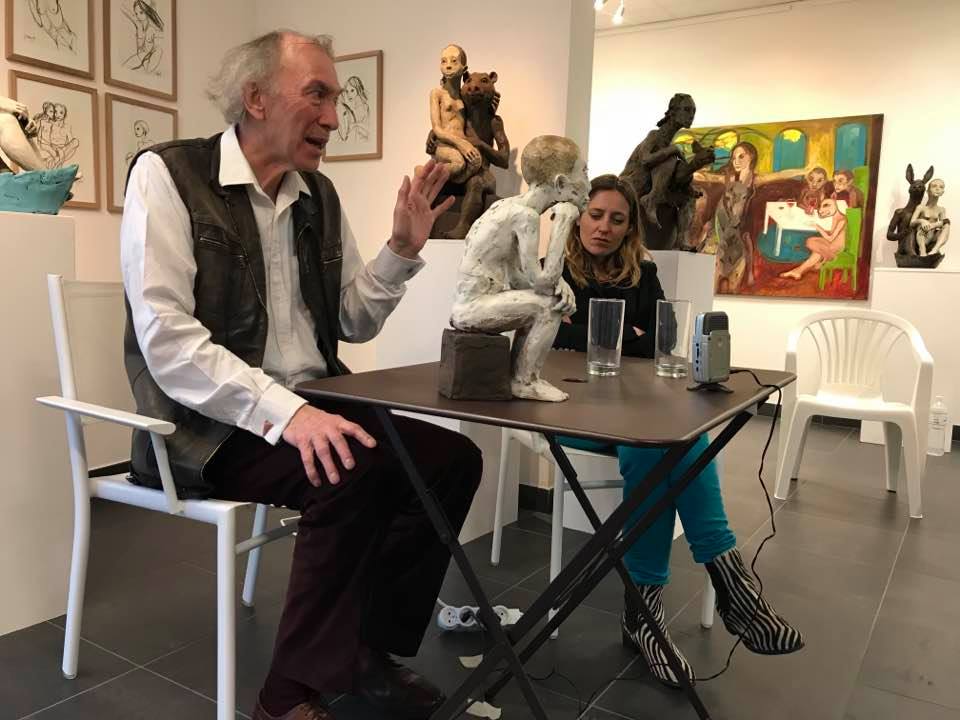

Galerie Espace 83, La Rochelle, conference with art critic Christian Noorbergen 2018. From personal Rūta Jusionyte archive

Rūta Jusionytė. Les trois mousquetaires. 115×89 cm

Galerie Art contemporain 22 ,Coustollet, France 2017. From personal Ruta Jusionyte archive