Have you noticed that what seemed to work yesterday might not work so well today?

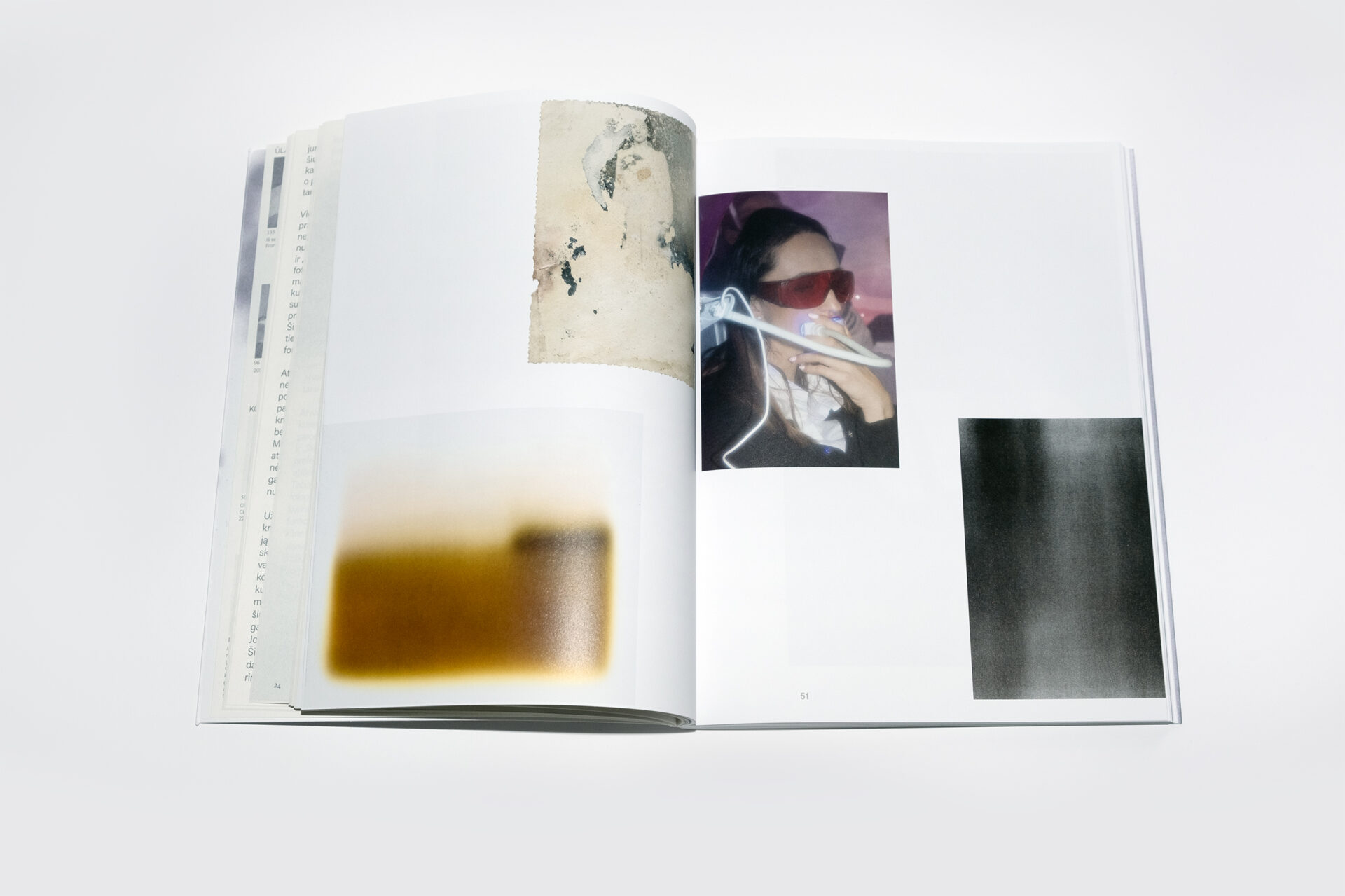

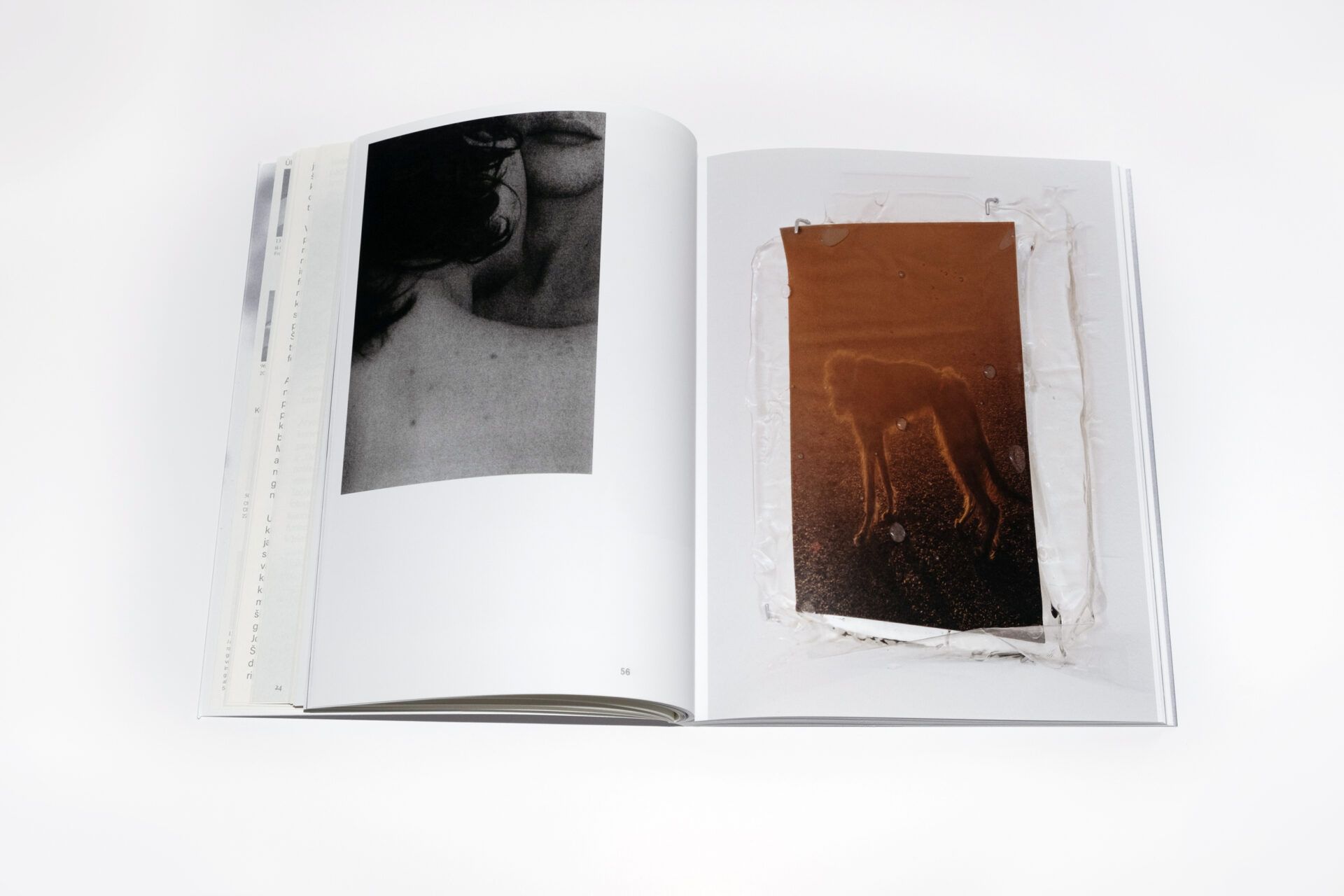

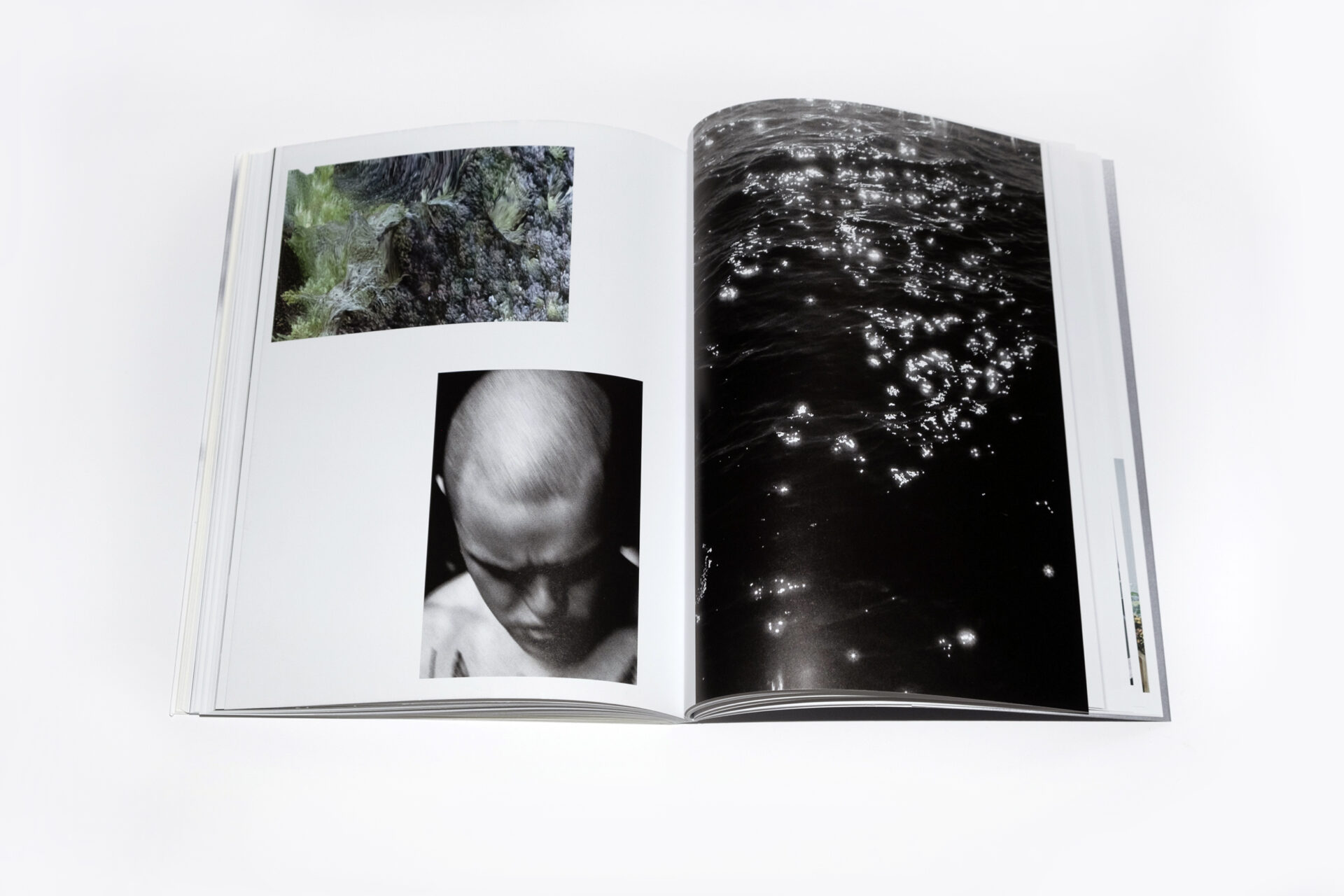

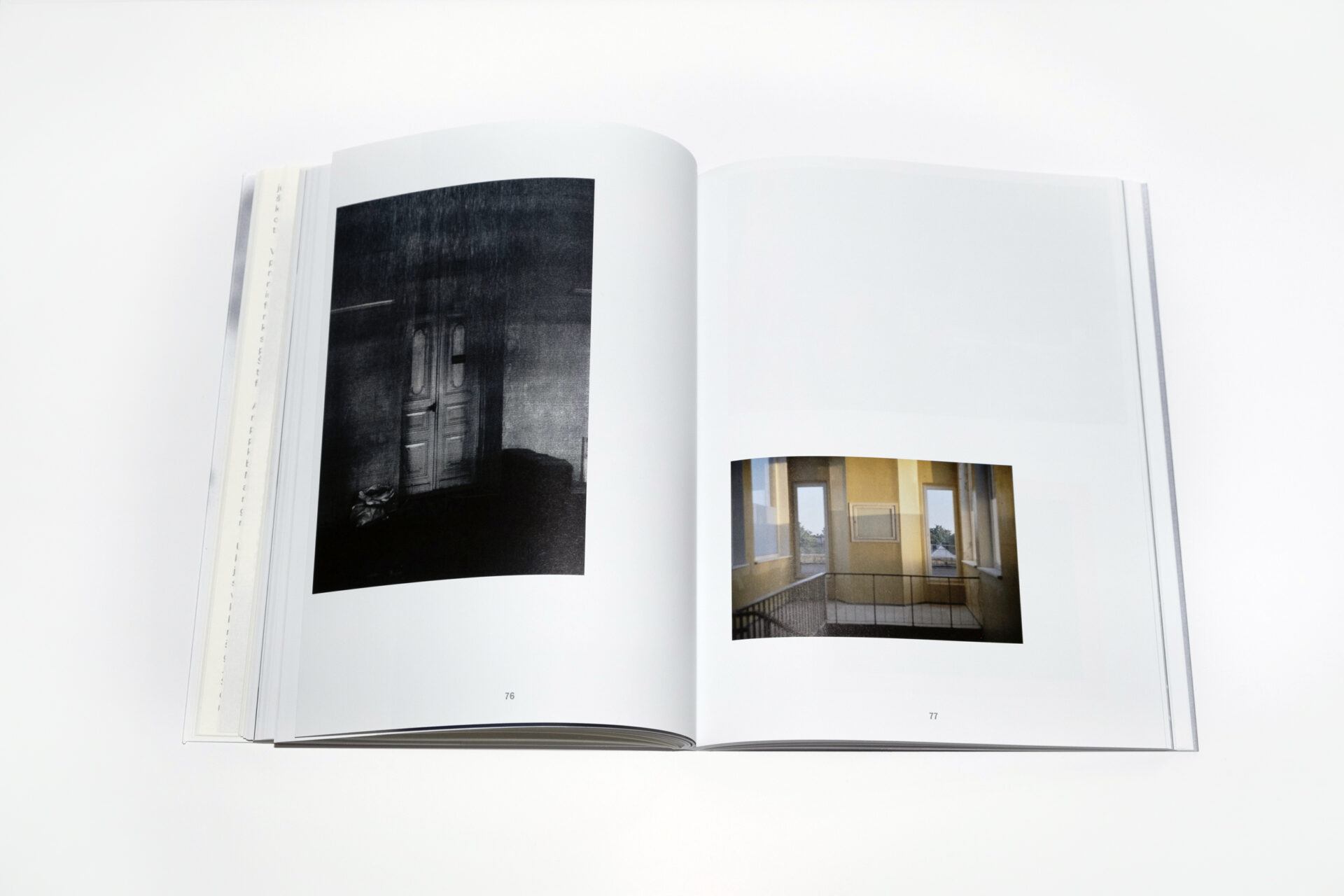

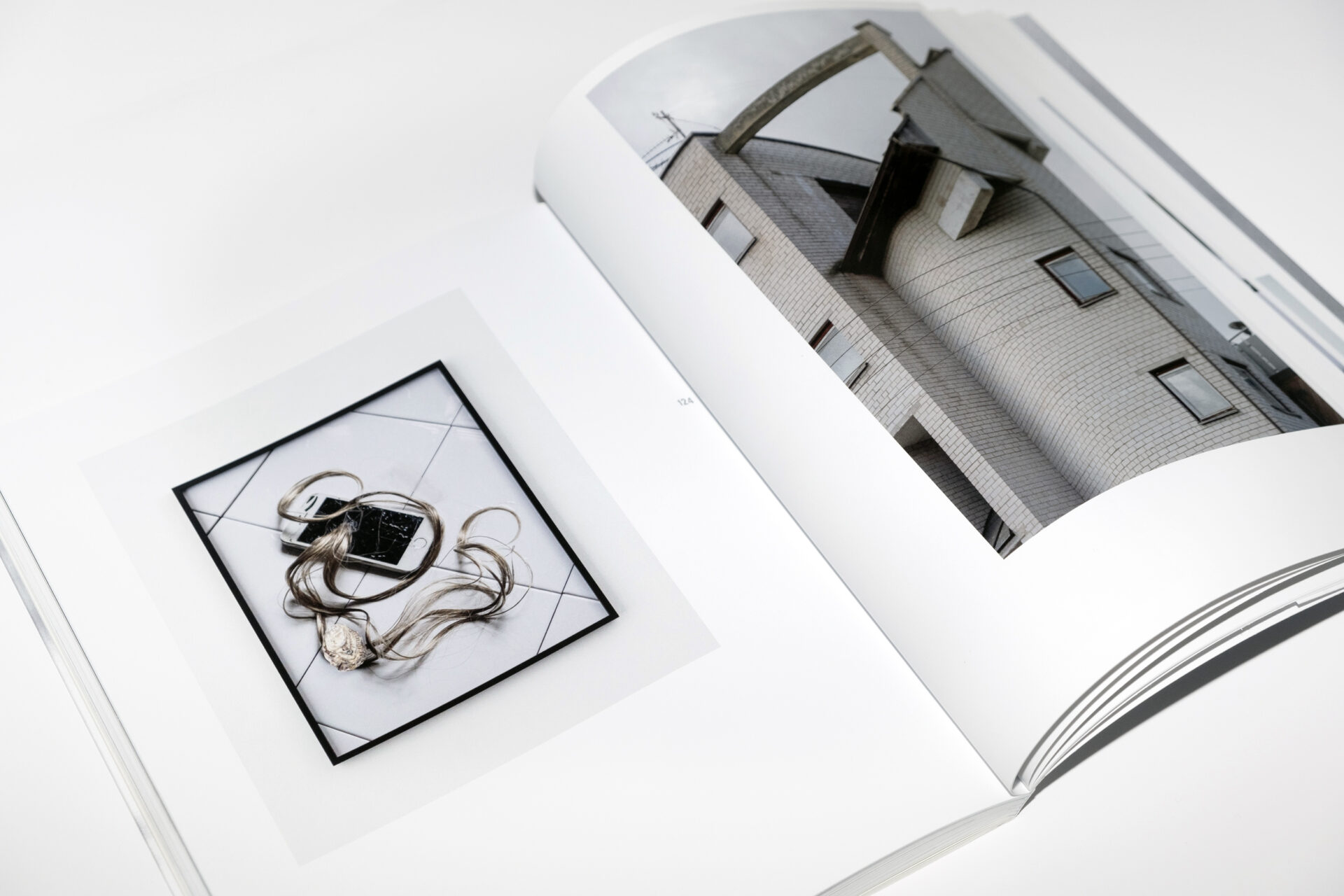

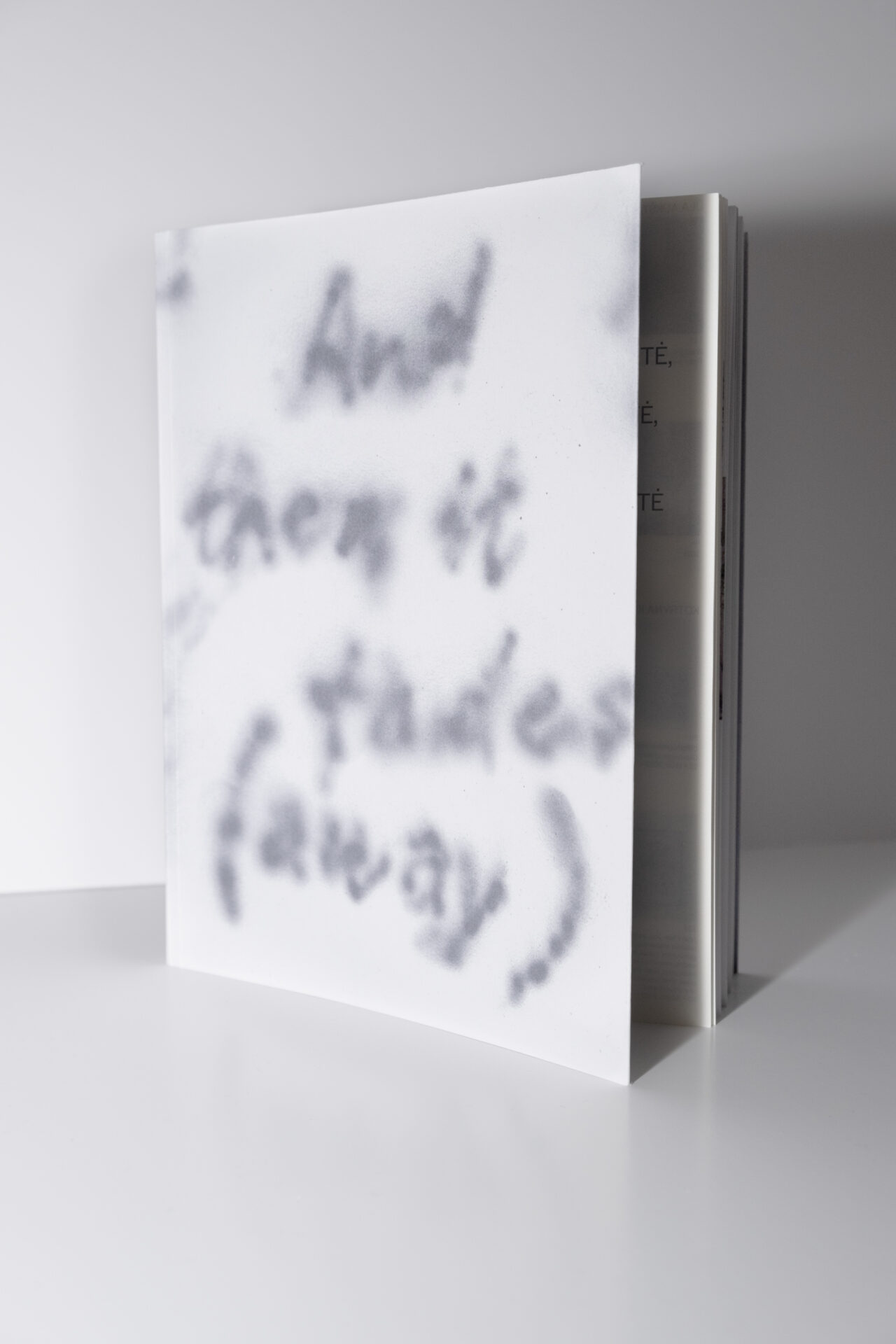

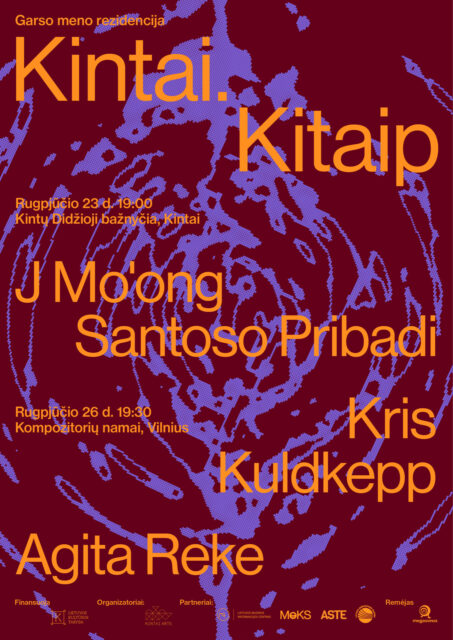

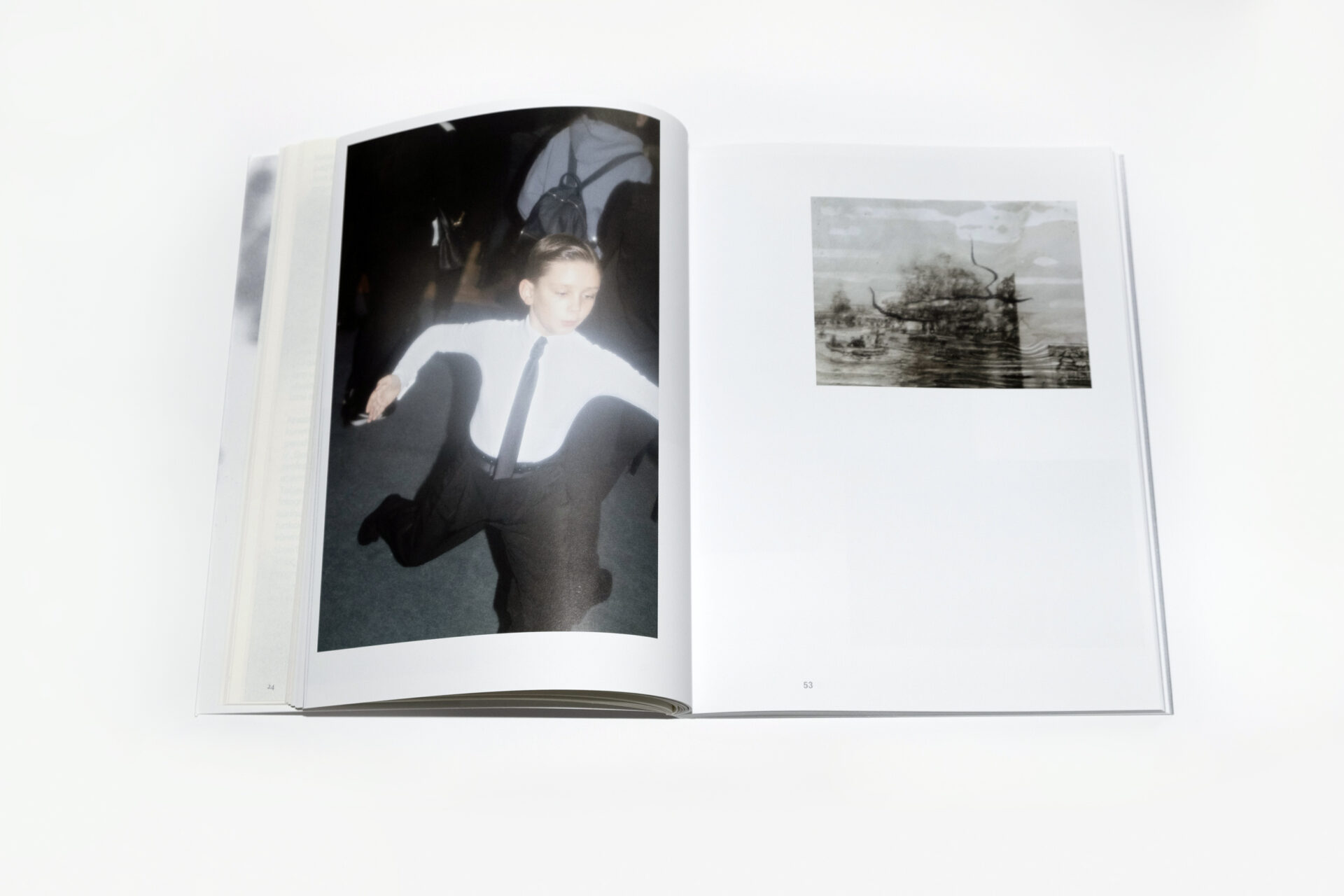

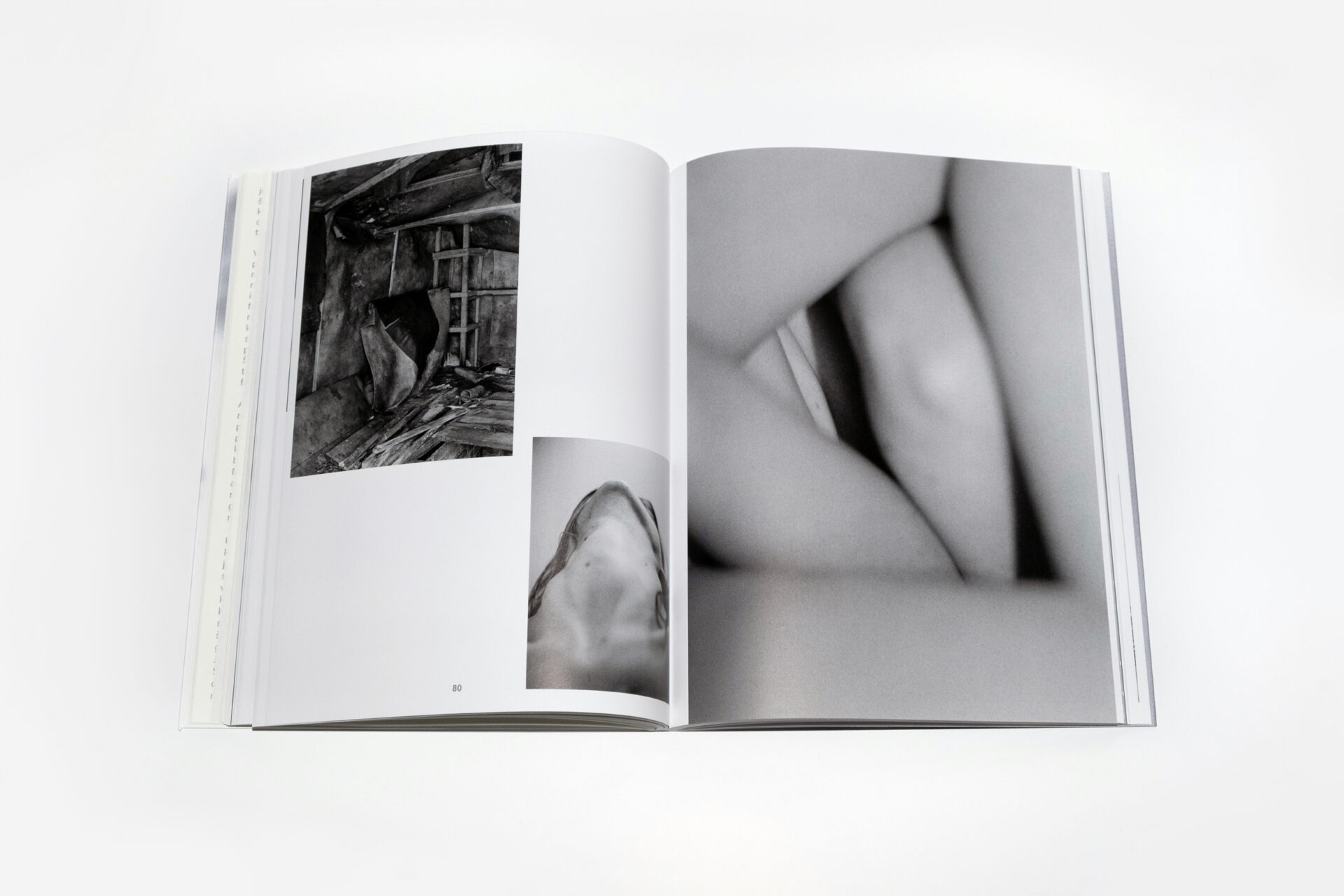

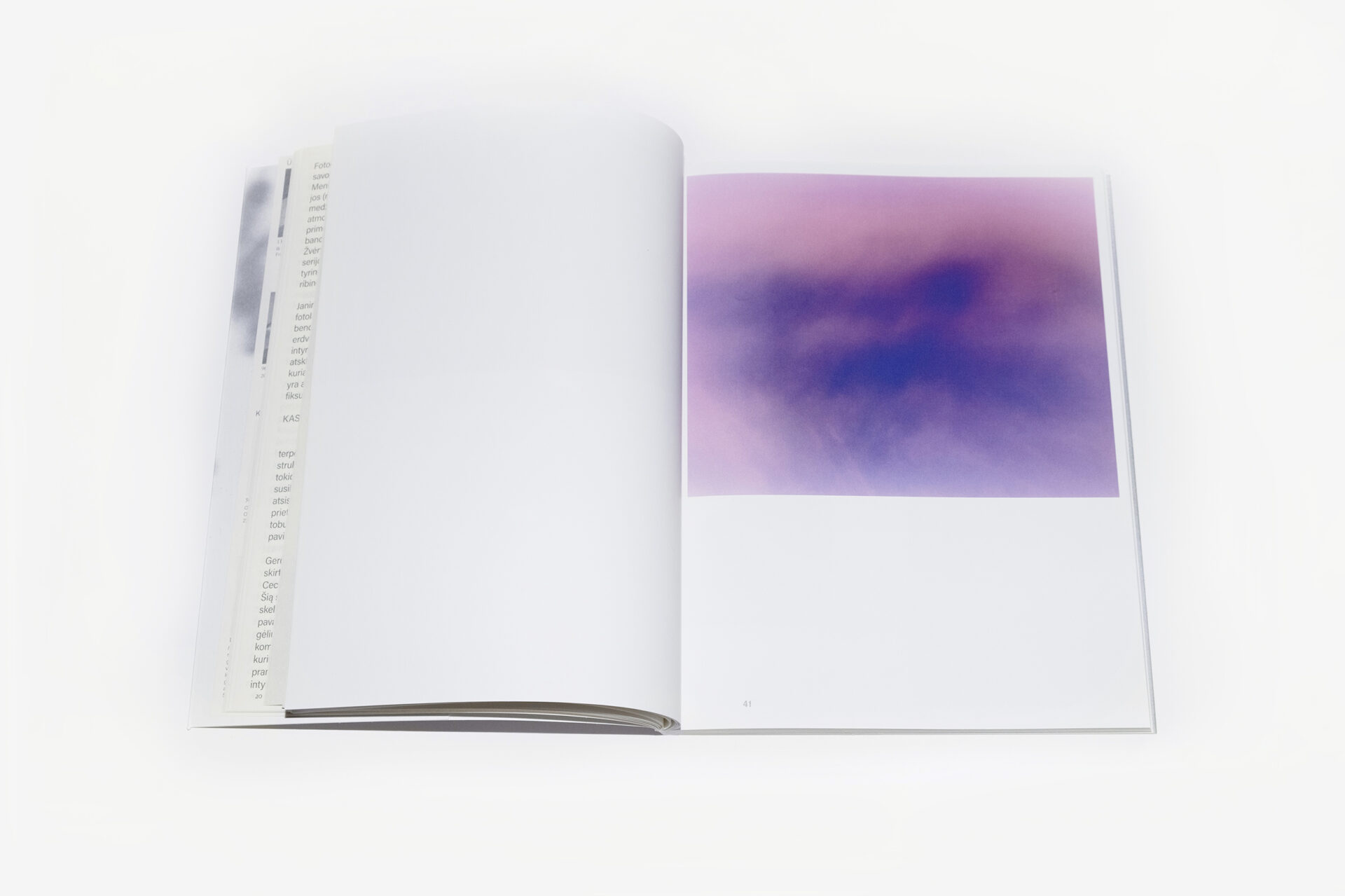

So writes artist Agnė Jokšė in a letter to an unidentified recipient in the early pages of the book, one dedicated to contemporary Lithuanian photography. With this, the book introduces a host of concerns plaguing the discipline of image-making, formerly known as the discontents of photography. That of mitigating expectation, critical un-seeing, strategies of obfuscation, latency, negativity. Wistful at times, frank at others, this missive’s letter foregrounds the many ambivalences of the publication: thoughts and feelings that are stewarded towards concretion in the editors’ introduction by Geistė Marija Kinčinaitytė and Paulius Petraitis. Despite the book’s reasonable proportions and heft, I sense sparing and discretion. The design by Monika Janulevičiūtė is unintrusive, weightless, airy. For the book’s cover, Janulevičiūtė airbrushes the words ‘And then it fades (away)’ onto a piece of paper and then scans it – a two-step process comprised of air and light that, by their very nature, speak of photography and the evanescence of images. Though lavishly illustrated, the spreads leave wide gaps and berths for marginalia and associative thinking and were arranged and sequenced by the editors. It is as if the generosity of space orients us towards a field of absences; towards the enigma as Roland Barthes had put it – that ‘a photograph is always invisible: it is not it that we see.’

The project evolved over an intensive period of research spanning 6 months, wherein discussions were held with those shortlisted from the open call, with respect to photography’s ambivalent status as artwork and medium. This marks another absence, for never do we learn of these conversations; the publication never cedes its virtue as artistic proposal, is never given over to the annals of heady research. The book is conceived in such a way that the artists were forced to relinquish authorial ego – entrusting the spreads’ arrangements to the editors, they submitted their work to transversal readings. Interspersed and interwoven throughout, images do not ‘belong’ by name to their maker except for in a simple legend in the front-of-book. Sans hierarchy, images of objects and bodies partialled and piecemeal float unmoored and, like so much flotsam and jetsam, frustrate full grasp. The looker is, in effect, immersed in a visual cacophony: a sprawl reminiscent of the installations we know well by Wolfgang Tillmans, or the endless scroll of our image-fluid slipstream: what in the contemporary we may also think of as new geometries of relation. For me, the book thus retains an aspect about it that configures impenetrability as felicity: the impossibility of knowing that safeguards the delicate being of aesthetic pleasure.

A spatio-temporal zone unto itself, the project teems with the potential of new dialogue, odd junctures, awkward mixity and visual frission. Such a project – from the open call to the early-stage ‘studio visits’, through to the publication’s spatialisation and partial dispensing of authorship – may be familiar to the curatorial discipline as something akin to a group exhibition. A better but different analogy comes to my mind: Marcel Duchamp’s La Boîte-en-valise (1935–66): a work editioned multiple times, a box of tricks, a dolls’ house: all Duchampian insouciance and obscurantist witticism. Taking the form of a suitcase which folds out myriad artwork miniatures – most including his Fountain and Large Glass – Duchamp flatpacks himself to the convenience of the artist-as-travelling-salesman. It’s a sort of jocular curriculum vitae: the hoarded wares of an itinerant, somewhat premature, artist’s retrospective. Repertoire and time capsule, Duchamp’s valise is now an archive: it petrifies an exhibition in a way that institutions, with their continually changing programs cannot. It turns artworks over to the archive even before it is given over to the museum. Likewise, And then it fades (away) occasions a collection of artists who may never exhibit together, which I lament, and therefore so cherish as speculative proposal. Indeed, many books exist to document exhibitions that have been made, but it is images – far more than sculpture, installation or performance – that lend themselves wholly to the site of the publication. The publication, in its turn, so willingly hosts the image without reducing or reifying it as documentation, such that these images intended as images stand within the publication, to me, as genuine works of art.

A spatio-temporal zone unto itself, the project teems with the potential of new dialogue, odd junctures, awkward mixity and visual frission. Such a project – from the open call to the early-stage ‘studio visits’, through to the publication’s spatialisation and partial dispensing of authorship – may be familiar to the curatorial discipline as something akin to a group exhibition. A better but different analogy comes to my mind: Marcel Duchamp’s La Boîte-en-valise (1935–66): a work editioned multiple times, a box of tricks, a dolls’ house: all Duchampian insouciance and obscurantist witticism. Taking the form of a suitcase which folds out myriad artwork miniatures – most including his Fountain and Large Glass – Duchamp flatpacks himself to the convenience of the artist-as-travelling-salesman. It’s a sort of jocular curriculum vitae: the hoarded wares of an itinerant, somewhat premature, artist’s retrospective. Repertoire and time capsule, Duchamp’s valise is now an archive: it petrifies an exhibition in a way that institutions, with their continually changing programs cannot. It turns artworks over to the archive even before it is given over to the museum. Likewise, And then it fades (away) occasions a collection of artists who may never exhibit together, which I lament, and therefore so cherish as speculative proposal. Indeed, many books exist to document exhibitions that have been made, but it is images – far more than sculpture, installation or performance – that lend themselves wholly to the site of the publication. The publication, in its turn, so willingly hosts the image without reducing or reifying it as documentation, such that these images intended as images stand within the publication, to me, as genuine works of art.

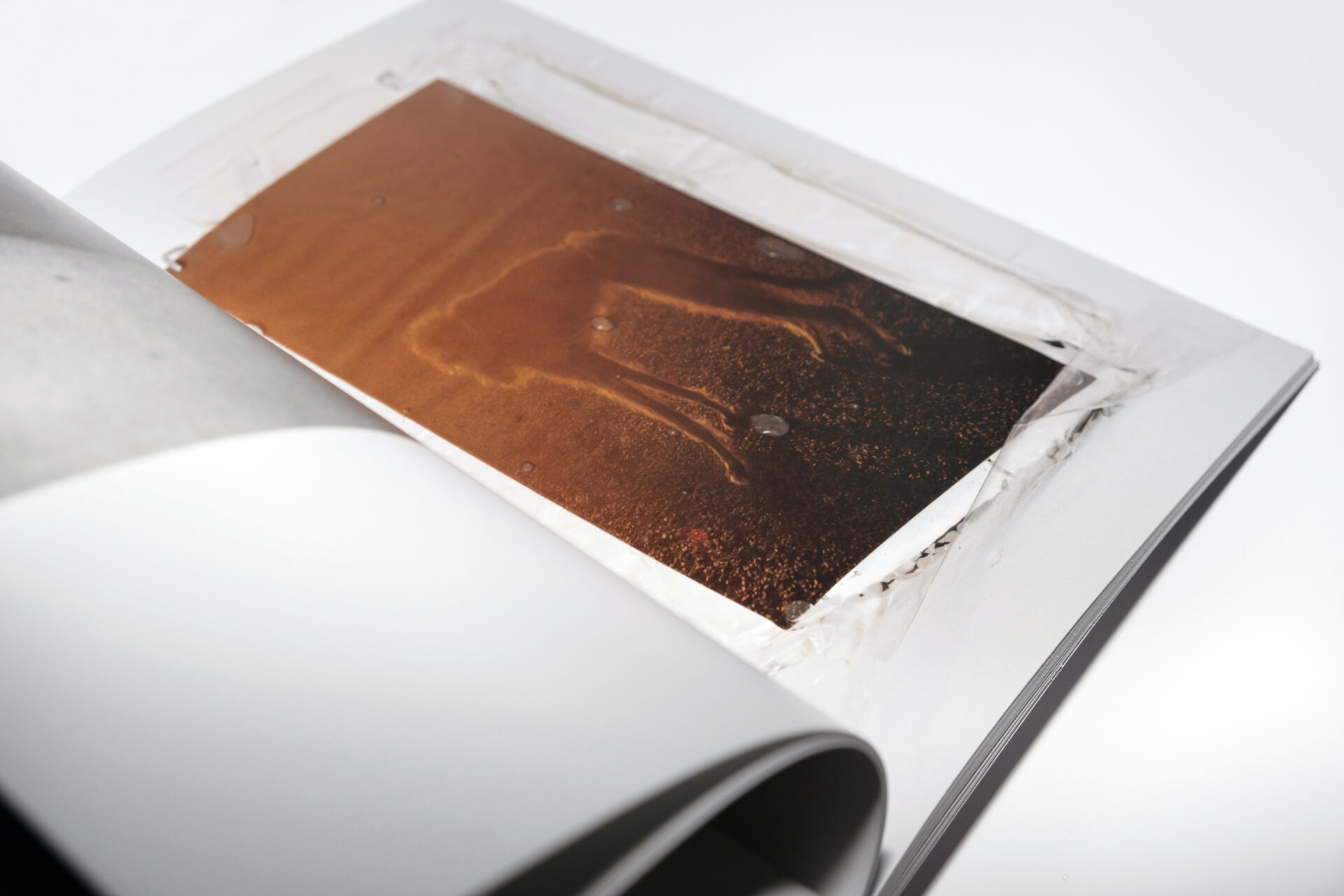

I re-read Barthes treatise in the first part of Camera Lucida (1980), which names the aspect of photography that is responsible for both its banality and uniqueness: its ‘lamination’ with the referent. It is precisely this that will forge a link between the photographic record and the idea of the archive as witness. But we must also consider what Hito Steyerl says of ‘the archive as a realist machine, a body of power and knowledge’ – those hidden machinations that require a critical un-seeing, to allow their omissions to come to light. Of the archive: we always make disclaimers about its scope and resourcing, at the same time, does every aggregate not immediately confesses its incompletion merely by existing? There is explicit reference to the concept of the archive, as the book’s introduction will attest; certain of the photographers put this reflexivity to work, exposing the meta-textual registers of the project. Images of storage units, like so many strange housings with their surfaces barricading matter from the dogged eye (Ona Julija Lukas Steponaitytė), confront us with one strategy of obfuscation. Elsewhere, fungal growth defile books, and mottled, water-logged found images teem with new orders of sense (Ieva Maslinskaitė, Pavelas Šalaikiskis). In making portable the referent, photography and by the extension the archive, are inextricably if not fatally bound to latency, material decay and the onslaught of time.

On portability: when asked about their findings through the course of their research, the editors offer a common denominator among their sample: an unshakeable sense of placelessness and non-belonging. Engaging with the ex-timacy of local attachments proper, it could be speculated that Lithuanian photographers have been fragilised by the historical and present-day political climate in the region. And yet any reader will see that the Lithuanian photographers collected in this book are, as much as their photographic contemporaries, universally interested in reforming the medium of photography and image-object relations (Vytautas Kumža). They are equally shaped by the idea of the image in jeopardy, its proliferation and mobilisation in the context of the news on war. Here, I am back in the realm of absences – I might also ask what it means to delete things repeatedly, to be forced to exorcise an event over and over again, just to survive. The issue then, is no longer about photography in terms of a subject-object dyad, but rather a media literacy, an acknowledgement that the ‘democratic’ image has already long been sacrificed to mass appropriation beyond any possible hemming in by tradition.

On portability: when asked about their findings through the course of their research, the editors offer a common denominator among their sample: an unshakeable sense of placelessness and non-belonging. Engaging with the ex-timacy of local attachments proper, it could be speculated that Lithuanian photographers have been fragilised by the historical and present-day political climate in the region. And yet any reader will see that the Lithuanian photographers collected in this book are, as much as their photographic contemporaries, universally interested in reforming the medium of photography and image-object relations (Vytautas Kumža). They are equally shaped by the idea of the image in jeopardy, its proliferation and mobilisation in the context of the news on war. Here, I am back in the realm of absences – I might also ask what it means to delete things repeatedly, to be forced to exorcise an event over and over again, just to survive. The issue then, is no longer about photography in terms of a subject-object dyad, but rather a media literacy, an acknowledgement that the ‘democratic’ image has already long been sacrificed to mass appropriation beyond any possible hemming in by tradition.

Still, the publication And then it fades (away) can be said to be a response to ‘tradition’, however obliquely. Further to experimental proposition and aesthetic joy, the publication occasions re-looking at the humanist tradition with which Lithuanian photography is identified with and known. For the identitarian exercise of supporting a national breed and brand of humanist photography has had a two-fold, mutually-reinforcing tension: the export of ‘Lithuanian’ photography has conversely entailed the internal privileging of it, figuratively and literally displacing those here, clearly not of the canon. The result, as we can see, is varied: there are those in the publication that dis-identify with the tradition, and there are those that dis-identify with not only the place but the medium of photography itself. Such are the discontents I alluded to in the introduction, hardly answerable in a review, at best a suite of questions posed by the editors of this publication. A wayward Henri Cartier-Bresson translation may warrant brief mention here: the English The Decisive Moment reads emphatically of image-maker-autonomy – find his 1952 French copy and title reads Images à la Sauvette, which translates to ‘Images on the Run’. A diasporic child myself, I celebrate the noble cause of ‘re-homing’ the non-sequitur in any capacity, and the way in which the publication is simultaneously restless and resting place. Insofar as the act of photographing is conceptualised as a great chase, let us consider the elusiveness inherent to photography: the image is fugitive, ‘it is not it that we see’.

Photography: Geistė Marija Kinčinaitytė