Headquartered on the forested outskirts of northern Vilnius, Rupert dedicates itself to ‘creating platforms for conversation, research and learning’.

The Alternative Education Programme (AEP) is one of the contemporary art center’s three core responsibilities, alongside its public programming and its internationally noted artist residencies. Despite its importance to Rupert’s vision, until recently the AEP was perhaps Rupert’s least well-known activity outside Lithuania.

That is changing. The AEP was founded on the principle of offering Lithuanian-based artists of any nationality another option to integrate their practice and begin their career outside the academic system. Since Rupert’s inception, the success of and the high demand for the residency programme has also brought more attention to the Alternative Education Programme’s open calls posted each year.

Students from all over Europe now arrive, as eager for an experimental, trans-disciplinary and comparatively inexpensive art education option as their counterparts already based in the country. The six-month, small-group programme invites a rotating cast of international guest tutors each year, artists, writers, curators and other cultural producers, to lead workshops and mentoring sessions with its students.

As Rupert turned ten this year, I spoke with the AEP’s curator Tautvydas Urbelis about the aims of the initiative, student demand for diverse learning models, and the overall state of art education.

Mary Maggic workshop by Monika Jagunskytė. Photo: Rupert

JL Murtaugh: How did the idea of alternative education at Rupert start?

Tautvydas Urbelis: Well, Rupert started as an alternative education. As it all happened before I started to work there, from what I gathered speaking with former employees and founders, there was a need. It all started ten years ago, and the local environment in education and art was quite different. I think one of the main needs was to get more information and catch up with what was happening “in the West”. It felt like the rest of the world was ahead, especially when it comes to juxtaposing different disciplines and theories.

There were people who were interested in the inter/trans-disciplinary approach, combining theory, philosophy, research and artistic practices, which was maybe lacking at art academies and universities, especially ten years ago. The Internet was different, and access to information overall, in some respects, was limited for some. In general, that exchange between Lithuania and the rest of Europe was not that smooth as it is now, especially for students seeking for what was happening in the arts at the time, wanting to be part of the conversation happening now.

The general need was for different types of knowledge, to be more dynamic, to be more daring,. Because, you know, the universities can be quite slow and struggle to respond to students’ developing needs.

JLM: Are there ways that Rupert is positioned to educate better than the Academy can?

TU: I wouldn’t say that one is better than another. I think it is more useful to speak about differences and what those differences can mean for students and shifting educational landscapes. The first thing that comes to mind is Rupert’s flexibility. It’s a smaller structure, it can transform itself more easily, and introduce new things much faster, without losing too much.

It’s also a younger institution, a group of people who are not so rigorously adhered to a certain school of thought or methodology. They are more flexible, more daring. That can really be felt with artists who want an environment that supports their idea of freedom. It offers space to accommodate their desires and needs, and also their failures and attempts to create what they want.

So the most significant difference is flexibility and pace. And enthusiasm – both to create, experiment and accept inevitable failure here and there. But I wouldn’t go as far as to state that this is what makes Rupert better equipped to do education. Education is a complex process covering a vast network of needs and competences.

JLM: Enthusiasm: less of the jaded quality that seeps into many educational institutions over time.

TU: People are less afraid of small fuckups. There is less pressure to maintain the status quo in order to justify one’s position, artistic practice, or even subjectivity. Like, you can use swear words from time to time here. It’s a privilege of working in an enthusiastic and flexible environment!

JLM: Would you say Rupert has a non-hierarchical structure? For instance, when you choose a programme, a theme for a year or longer, how is that generated?

TU: It depends on how you understand hierarchy. We have clearly assigned roles. Because it’s such a small team, these roles overlap when needed. The staff come together to choose the theme, for example.

At Rupert the director has quite a lot of administrative responsibilities, and oversees the general trajectory of the institution. That trajectory comes from the work by Rupert’s curators. They propose a thematic trajectory, making programme invitations, selecting residents, and alternative education participants. Other staff can and do join in those choices, but the main work for it is done by the curatorial team.

We also have a communication manager, who proposes how we promote the activities, and a coordinator to handle how they’re implemented, particularly when it comes to the programme’s structure. We understand our strengths, and that we have a separation in our responsibilities. You can identify it as a hierarchy, but it’s more about being able to help each other and manage the workload.

JLM: Because there’s quite a lot to the programme to implement, right? It’s complex. I know you haven’t been there the whole ten years, but as you understand, how has the Alternative Education Programme changed? Has it broadened and developed over that period?

TU: Change is probably the key word to describe Rupert. The institutional composition is very dynamic. There is a defined framework in our programmes, and there is an unwritten one, something like a vibe.

From within, it seems clear to me, or if someone is following Rupert over its whole ten years, there is a recognisable identity.

Wait … what was the question?

Laura Garbštienė workshop by Medeina Usinavičiūtė. Photo: Rupert

JLM: Well, I was looking for ‘how’ it’s changed. Where did it start, and in the time you’re aware, what changes has it undertaken?

TU: What I learned, especially in the Alternative Education Programmes, is that it became more structured and strategic, without sacrificing the experimental, dynamic qualities of

the institution. We came to see better who we are and what we are doing, and especially how we can help others. It was extremely helpful to have this grounding and understanding.

From that point, you can develop things, and go wild if you want, be as intense or as experimental as you want. Still, you maintain safety measures, guardrails, that keep the institution from flying off its tracks. It allows us to maintain our integrity.

Rupert started as something like a passion project. Passion runs through it, always verging, lingering on burn-out, which is inevitable. You invest so much and receive so much back in return. It’s an intense dynamic. For the Alternative Education Programme, it was not only the intention that was experimental but also the structure. It was implemented by doing.

[For example] working with specific themes for programming was something new, and quite an experiment. Before, it was based on one thing: to change something fundamental about education and implement new ideas. A testing ground, a laboratory to try new ways of learning and just do them. It’s a place of constant refinement, where ideas could be very fruitful, and yet also expose their limitations.

That’s what’s still happening. Now there’s a little more structure, incorporating feedback, which helps us avoid the echo chamber where we hear only our own ideas.

JLM: When you say feedback, you’re talking about feedback from those learning on the programme, or the wider context too?

TU: I think both, but especially for former residents, employees and alumni, who spent time at Rupert and have returned in a different capacity. That feedback really helps us to see what’s changed and what remains consistent.

JLM: What are the models which you, in the time you’ve been involved, or Rupert, looked at originally? Do you see similar initiatives in the region or abroad that especially influenced or inspired Rupert’s Alternative Education Programme?

TU: I can’t speak for others, I’m sure there was. When I started to work there, and I’m not coming specifically from an art background, I imagined there were much more such spaces. But actually …

JLM: There’s not many.

TU: Yeah [while] there are a lot of smaller project spaces that experiment [with this] unfortunately they don’t usually last for a long period of time. Now, though, I really cherish the non-art influences. I think it’s the non-art spaces that are more influential for our institution. At least for me.

For example, the restaurant Noma in Copenhagen. I see it as one of the biggest influences on our alternative education structure. My years of experience of being part of squatting communities, for example. I’ve had to reconcile with that past. I’ve learned from working at Rupert how to reintroduce some of those hands-on experiences into [practical] theoretical or institutional frameworks.

Then, of course, there’s the longstanding educational institutions, like the Dutch Art Institute, Casco, School of the Damned, and the Mountain School in the USA. They all have many inspiring things and lessons to teach. Another is the Serpentine Gallery. I value their ability to nurture research. That’s something we need to do more in the future, to have more space for internal research and development. Not everything has to be public, we should reserve more space for experiments.

Laura Wilson workshop by Ieva Juodytė. Photo: Rupert

JLM: Project development. That’s interesting you mention those initiatives, they’re all references I can clearly connect to what’s happening at Rupert. As you say, in the art context, there aren’t many. I have a similar concern at Autarkia1 or with Syndicate2, there’s a few examples that match, you have to interpret elements of what others do that applies to your circumstance.

Noma is an excellent example, actually, as a model that champions experimentation.

TU: Their internal structure, their creative approach, their environment of daring-ness.

JLM: Another topic, the audience for alternative education. It’s changed a lot over the last ten years. Originally, the AEP was very locally focused. In my view, it’s almost become, not a rival to the residency programme, but certainly another residency-style offering. People are coming from much further away who are attracted to Rupert’s mode of learning. How have you responded to that? I’m sure you’re aware of it …

TU: Oh, sure.

JLM: How do you feel about it?

TU: Yeah, I’m well-aware of it. It’s one of the main questions our team discusses. Especially during conversations for our strategic planning and funding applications. The original intention was, and I must emphasize, still is, to help young local and Lithuanian artists. At the beginning, this aim was direct and obvious; now maybe less so, but our intention remains there. Eventually we had to choose. We began receiving more applications from abroad: good applications, people who are dedicated and willing to come to Vilnius for six months, at one month’s notice.

JLM: It’s a big commitment.

TU: It’s amazing, and quite crazy. Then we had to ask ourselves, should we introduce a quota, local artists versus those from abroad. The decision was not to have quotas, but to find other ways to open up the programme, to see how benefits for local artists could go beyond just accepting them. We only accept eight or nine people each cycle, so it’s very limited. The support then can be very substantial and influential. But it’s still only nine people, so the question was how can we expand.

We introduced a few measures starting this year, offering public lectures and collaborations with Vilnius Art Academy and the Vilnius Tech. It’s still very fresh, where we have a workshop, but the day before the same tutor will give a ‘public lecture’, but it can be an artist talk, performance, anything we and the tutor come up with. That usually happens at Vilnius Art Academy or Vilnius Tech, with a special emphasis on students, but open to the public. Hopefully, that will not only allow us to share the knowledge of these amazing tutors, but also to create a space where the participants can mingle with people outside the Alternative Education Programme. That is extremely valuable, because the people that come here for six months, with loads of energy and great commitment, can really elevate and inspire others, creating very nurturing and mutual relationships with the local art community.

That’s one of the tactics we use. Another is the shared studios at the former sewing factory (now Tech Zity Vilnius) that the Alternative Education Programme participants now have for their use and to hold public events. Running a project space is quite a good exercise for the participants, and gives the public better visibility of the programme. So far, we’ve received many guests not only from the art field, but also from the neighborhood.

We will also have a special publication dedicated for this year’s Alternative Education Programme. So these measures are our first attempts to open up the programme without introducing a quota, keeping our primary focus on support for local artists, but in different ways.

JLM: It’s interesting that the programme was conceived as a way to bridge a perceived distance [in Lithuania] from what was happening in the wider art community. Now, by attracting these international practitioners to come here, don’t you think that shows a major lack, a shortage of alternative education models elsewhere?

TU: Yeah, of course. I think the question is even about the overall understanding of education in art. That’s why now, different types of short programmes such as summer schools signify different attempts to reconfigure education, taking the means of learning into people’s hands, outside traditional institutions. Universities maintained and enabled the feeling of a lack that you mentioned. Was it actually a lack, or the limits of a traditional university setting? That’s quite a question, and it’s more for the future to answer.

Whenever students learn in a big, sometimes sluggish institution, you can feel the world outside is much faster, richer, more nurturing. Alternative educational models can alleviate that feeling.

If the traditional university contributes to the feeling of ‘lack’, then that is a clear signal in favor of what we’d call alternatives.

JLM: What is the local response to all this? As you say, Rupert presented an alternative to what is already offered in traditional settings. So how is your interaction with the Academy or other institutions in Lithuania, regionally or abroad?

TU: The way I try to perceive it is not as an alternative to the Art Academy, but an alternative by combining several approaches, joining the University and outside contexts, having voices that are in favor of the university approach, and those that are adamantly against it. Navigating those different approaches, methodologies, schools of thought: that can create a fulfilling alternative, meaning an alternative which isn’t dependent on its ‘opposite’.

In its earlier stages, maybe it was more intensely positioned as an opposition to traditional models. Now we have generated enough knowledge, baggage and experience to create a programme that isn’t reliant on an adversarial relationship with the universities.

The relationship with the Academy is in understanding our differences. We attempt first and foremost to speak to the students, to show them they don’t have to see themselves as ‘suffering artists’ under the yoke of the university. You don’t have to ground your subjectivity as an opposition to the scarecrow of the Other, be it university, the authority or the institution. That’s the dynamic, that’s the tension that inevitably exists. It shows our confidence to engage in conversations with this ‘other’ and often find that some tensions were quite artificial or projected. Of course some aren’t. We can collaborate yet still feel good about our differences.

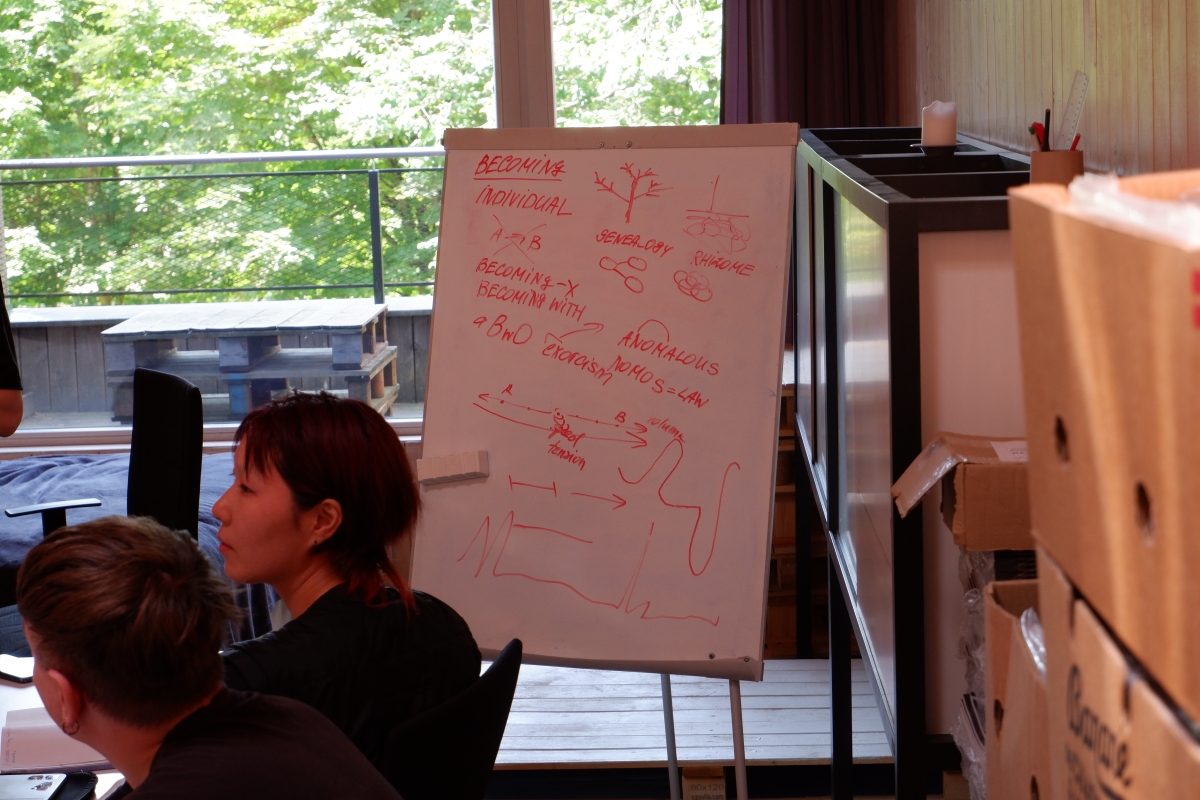

Áron Birtalan and Gabriel Widin workshop by Tautvydas Urbelis. Photo: Rupert

JLM: One of the ways I see the approach of Rupert’s Alternative Education Programme differing from the local universities’ is the use of theming. You use themes to align the teaching over a period of time, which not only defines the programme in terms of who the tutors are, but obviously attracts students who are more interested in that topic than others. The current theme is ‘Magic and rituals’. How did you arrive at this specific theme? Also, why is theming important overall?

TU: Most of my colleagues and I inherited the theming and the theme. It was originally conceived by the previous team as three themes over three years for all of Rupert. First dealt with institutional critique, then came ‘Care and interdependence’, and the last ‘Magic and rituals’. After the year of ‘Care and interdependence’ we had a discussion whether we should continue with ‘Magic and rituals’, because none of us had participated in the original meeting when the theme was proposed.

We decided to continue because it posed an intriguing challenge. It made sense and I explain [Rupert’s original thematic sequence] to myself as a long, introspective look at a nomadic educational initiative becoming an institution.

Institutional critique was an inquiry into what an institution is, how it functions, what its shortcomings are, all those things. Then came ‘Care and interdependence’, more of an attempt to look at who, outside the art scene, can access what we do, working with different marginalized communities, looking at their access, or more often the lack of access, to art in general. Finally, ‘Magic and rituals’ looks beyond what is currently possible outside current discourses and frameworks, finding what sits on the periphery of knowledge, what might be deemed unworthy to be research or institutional programming. To look at the things that are not yet here.

With general theming, one can say it provides the structure, or paves the way for a structural approach. Themes can consolidate the approach and direction. Themes also correspond to the team’s research interests, and spark conversations with potential collaborators.

So our approach to people we found interesting wasn’t only ‘We like what you are doing, come and do something with us,’ but rather ‘We are working on this broader theme.’ I think this proposition is more inspiring. Especially when you are working collectively towards something new, it really helps to usher the process in a direction that is exciting to yourself and the people you are working with. So I think that was transformative for the institution.

[Theming] has a different relationship with each of Rupert’s three programmes. In the case of the Alternative Education Programme , there are four main pillars which help to communicate our initiatives. One is the theme, which applies to the whole institution. Second, there is theory and research, the original impetus for the Alternative Education Programme to emerge. You know, all the brainy stuff.

Third, the trans-disciplinary approach, which is especially valuable considering the short length of the programme. Even with a group that broadly follows a similar approach, trans-disciplinary activities provide a special means for students to access how their peers work and what their methods are.

Finally, the practical aspect, which has become more important recently: practical knowledge. You can have an artist who does wonderful work, but struggles to prepare an invoice; or who struggles with financial stability or subsistence; or someone lost and frustrated in paperwork and contracts; or who uses over-conceptual writing in funding applications. We try to introduce practical knowledge as a type of career development, learning to adapt to various situations and bureaucracies.

JLM: Now that you’re at the end of this three-year theme …

TU: Four-year, because we decided with ‘Magic and rituals’ that one year wasn’t enough, especially with the last two years of global events.

JLM: So you’re going to change the approach. What are you thinking of for the next stage? Maybe you can’t reveal what yet, but how have you used the experience with the pre existing theming in developing what’s next?

TU: There are a couple of main aspects we want to reduce, and a few we want to strengthen. So the ones we want to strengthen are for creating better dynamics between Rupert’s three programmes, the residency, AEP, and the public programme, making the connections more seamless and fluid. Another aspect is learning how to communicate immaterial processes that happen within the institution and to continue developing our vocabulary that contains not only exhibitions but also workshops, journal entries, podcasts, publications and many other open-ended attempts to embrace the processual and the ephemeral.

We want to learn how working with themes can help our overall structure and to establish a structure that is fluid and complex from within, allowing us to retain the structural integrity and dynamic approach, without overwhelming our collaborators and the public.

Domas Noreika workshop by Tautvydas Urbelis. Photo: Rupert

JLM: That’s interesting. In some ways then, do you see Rupert’s different activities with residencies, education and public programming coming closer together?

TU: Yeah. That’s one of the biggest challenges for the future. For example, participants of the Alternative Education Programme are currently working at one of Rupert’s studios in the city [the former sewing factory], and that project space is an attempt to have more of a research and development phase in our programme. Not to have separate phases like, ‘now we are preparing’ and ‘now we are implementing’, but to have them overlap and create continual pockets of research and development. We also have to find a way not to overwhelm ourselves, or get overly entangled in these complexities. Suddenly you have a public output that doesn’t appear as a Public Programme.

JLM: Speaking for yourself, what would you like to see in the future from the Alternative Education Programme ? Say, in the next five years.

TU: I see it integrating seamlessly with the public programme, and having a healthy relationship with the residency programme. At least on the public level. Internally, we’ll stay the most experimental part of the institution, allowing ourselves to try new things, to have time and acceptance of failure. Also, I’d like the Alternative Education Programme to develop more connections with similar arts programmes, exchanging and sharing knowledge with those institutions. Currently we are working on that. As well as looking into and integrating some of the aspects of emerging technologies around web3 that can transform our organizational and funding models. Working on that as well.

It’s clear that traditional university structures no longer accommodate all student needs. More interaction will generate unforeseeable results. These results will define the future of art and alternative education. That will create energy and establish the knowledge that allows people to see they don’t have to rely solely on the university. There can be equivalent options you can choose. Art and culture are ready for that now.

JLM: I’ve observed that the tutors and invited guests on the AEP are trending away from exclusively [working in] the visual arts. You’ve probably seen that in students, that is the course of contemporary practice. I’m interested in these alternative education models, particularly with your mention of Noma, that they end up reaching a broader audience than the intended target. So that people operating in relation to art, but perhaps not mainly art, are attracted to this type of initiative.

TU Yeah, that’s one of many goals and ‘contemporary practice’ is a good way of naming it! It also comes from my own experience, my background in philosophy and political science. I benefited from experiencing a transdisciplinary approach. It eased the stiffness of academia. Now it’s easing the conceptual insecurities that often prevail and disable your ability to articulate yourself, or how to do things in order to be ‘legit’ in certain fields. Those fields have plenty of unwritten rules. Everyone already inside a field seems to know the rules, but in the end they might just be strange residues of attempts to maintain status quo and social capital. It’s important to create a space outside of what is perceived as oppressive rules – real or imaginary ones. If an institution dares to go into territories perceived as unworthy, that can be inspiring; an institution willing to step in and be unafraid of the critique and mistakes that may follow. But it’s tricky and you have to be careful.

So yeah, we are good with people who find themselves figuring out how to be “in art” or how “not to be in art”. For example, most of our interns are coming from non-art fields. Things are constantly changing and embracing those changes often works better than trying to compartmentalize.

In the end you don’t need to ‘dumb-down’ the discourse. You can maintain the same intensity but distribute it in different ways. It’s about having the necessary space for experiments to percolate, and to sift out the unsuccessful attempts.

JLM: What’s something you’ve learned as a result of this programme?

TU: [Laughs] It’s absolutely transformative. I could go on forever.

I learned to relax after academia. To see that there are so many exciting things, if you allow yourself to embrace the unknown. To make active decisions, but remain open to experience. To be humbled by the people I work with. To allow others to show the way, or one of many ways.

That was the most informative. To have educational or interpersonal space that challenges my preconceptions. Sometimes when Alternative Education Programme participants or residents come, they have art institutional prejudices, assumptions of what a curator is. It creates an odd power imbalance. One could play that out manipulatively, that an artist and a curator are in radically different positions and have different knowledge. Basically different worlds. That’s true, but to a certain extent. We also have quite a lot in common. I think we are allies, but a bit different. Ok, sometimes quite different. We can be playful and experimental. We can admit our power imbalance and hierarchical structures, but by acknowledging them we might be able to change them together.

JLM: This is more of an observation, but the people you’ve invited to the programme recently, it’s harder to say whether they are exclusively artist, curator or musician. And they’re not necessarily ‘slashes’ either, artist/curator, artist/musician. They are experts in independent fields. They sit side by side. You use the word trans-disciplinary, but I see it as more than that. It’s multiple expertise, instead of a little knowledge in many areas.

TU: To be honest, I still feel weird about all those categories. Curator, visual art, trans disciplinary … When I started to work at Rupert, I had to figure out what the fuck a curator was.

JLM: [Laughs] … I’m still trying to figure that out.

TU: Yeah the struggle is real but now I have embraced that question. Not as something I lack, but as something that allows one to absorb knowledge maybe differently. You try to capture those differences to do something that wasn’t in the initial premise.

We are inside endless information flows and can accumulate them for periods of time, in various roles and subjectivities. Still, the boundaries between disciplines already are, and becoming, I wouldn’t say really fluid. That’s more nurturing than identifying someone in a singular role. Taking those roles can be fun, but it’s also quite arbitrary, even detrimental.

JLM It’s as we discussed with Rupert, maintaining fluidity but building appropriate guardrails. Building a framework that allows things to move within, a walled garden (?) that is larger in scope than what a traditional institution can provide. That it’s down to the individual.

TU What I learned, especially at the beginning and even now with ‘Magic and rituals’, is that for some magic and rituals are completely internalized practices. It is their life, their world. While for others it might be a more of a research topic.

Then there was a question: is it possible to create a space where these different worlds coexist and how care can be exercised while preconceptions are alleviated. But two amazing years proved that it is possible! Sometimes not easy, but always rewarding. It requires quite a bit of structure, complexity, thinking and equal amounts of “letting it go”. And let’s not forget enthusiasm and humbleness – these things can bring you a long way.

Denis Petrina seminar by Tautvydas Urbelis. Photo: Rupert

Denis Petrina seminar by Tautvydas Urbelis. Photo: Rupert

NOTES

1 Autarkia (autarkia.lt) is an artists’ day center in Vilnius. It is a service-based independent arts initiative, with parallel functions as a restaurant (Delta Mityba), an events venue, an arts producer, and a project development house. The author is currently its artistic director.

2 Syndicate (syndkt.com) is a liquid arts institution. It operated physical gallery spaces in London, Cologne and Los Angeles through 2020, and now functions nomadically. The author is its founder and director.

––––

Rupert is an independent, publicly funded center for art, residencies and education, located in Vilnius, Lithuania. Rupert has been operating since 2012.

Tautvydas Urbelis is curator of Rupert’s Alternative Education and Public Programmes. He is a curator, philosopher, researcher and critic. He has degrees in philosophy (BA) and social and political criticism (MA) from Vytautas Magnus University. Urbelis has participated in programmes on philosophy, architecture and critical urbanism in Vilnius, Berlin and Rotterdam. He is the co-founder of two independent cultural spaces in Kaunas, and is one of the curators of the Kaunas Architecture Festival. He is currently developing a project devoted to lust and architecture research, and writing for cultural and art publications.

JL (Liam) Murtaugh is founder of the liquid arts institution Syndicate, and is currently artistic director of Autarkia in Vilnius. He is an artist, curator, writer and consultant. Over the last decade, Murtaugh has produced artist projects in London, Cologne, New York, Mexico City, Chicago, Athens, Vilnius, and other places. Later this year, he will be a resident artist at Lower Cavity in Holyoke, Massachusetts, USA, and next year at the Nida Art Colony. Originally from Chicago, he is now based in Vilnius and London.

Disclosure: the author is a frequent guest tutor on Rupert’s residency programme.