This text began as a prelude to Pam Virada’s exhibition A Trick of Light, presented at the Meno Avilys Cinematheque in mid-October. In Pam’s correspondence with Ona Kotryna Dikavičiūtė and Gerda Paliušytė, both curators at Meno Avilys, the three of them share their views on memory and intentional forgetting, the shadows of cultural history, reconciliation with the past, and Thailand’s ghost stories and Lithuanian folk tales in which the feminine line prevails.

Gerda Paliušytė: During our first conversation about Pam’s forthcoming exhibition, although the themes kept changing, one of the connecting threads was the topic of memory, or rather the loss of it. Afterwards, I kept coming back to a few moments: how all the photographs from when Ona was a baby were accidentally lost and how she pieced together that original image from external details, such as the resemblance between her and her brother, whose photographs did survive; or how Pam’s mother creates separate albums on her phone for each family member, including Pam’s cats Tong Ngern and Tong Pond, and how this helps her keep a linear sense of time. It seems to me, more and more so, that the practice of collecting and recreating images, or the sense of losing a precious memory, could be an introduction to describing Pam’s practice and her exhibition in Vilnius, but maybe I’m wrong? Anyway, I would like to start the conversation with the topic of memory and what role it plays in Pam’s practice as well as in Ona’s work as a curator.

Pam Virada: Thank you for igniting the topic of memory. I feel that memory falls into the realm of the mysterious and the intangible. Its elusive nature, coupled with its fleeting and ever-shifting state, compels each of us to grapple with what remains of it and what it might signify. This topic encompasses a vast expanse that interweaves history, identity, the ordinary, and the fantastical – fundamentally encapsulating the essence of the human experience. When memory is lost, it casts a shadow upon us. I guess I’m interested in that state: the paradox of reconciling with what has disappeared, whether through the pursuit of representation or through imaginative reconstruction. The endeavour to resist forgetting, to retain, and to recollect forms a perpetual cycle; there are such varied ways to create mnemonic apparatuses that try to fortify the stories we tell ourselves and those around us.

Ona Kotryna Dikavičiūtė: The notion of memory plays an important part in my curatorial and academic work, as I am interested in home movies and the interplay between the personal and the cultural in them. The simultaneously subjective and objective nature of home movies, I believe, evokes a universal emotional resonance and a sense of nostalgia – a yearning for a past that was never truly owned, yet at the same time remains lost. In a way, home movies serve as a conduit for individual memories. These ephemeral artefacts unavoidably also encompass hints of all that remains hidden: pain, loss, secrets, decay and forgetting. Does the concept of memory come into play in your curatorial and artistic practices, Gerda? I feel that the notions of cultural and/or personal memories, which resurface to influence us personally and us as a society, are relevant in your and Pam’s works, too. I would love to hear both of your thoughts on this.

G.P.: I often see my artistic and curatorial work as a tool for questioning cultural history and addressing its reliance on both stereotypes and antagonisms. I am interested in exploring how personal experiences are situated in a specific landscape and the popular imagination. For instance, I am currently working on a feature documentary film centred around a choreographer and dancer who used to be famous in Lithuania in the late Soviet times. He is still looked up to and well-regarded, but only within the local dance community and specific circles. For those who don’t know his past, he’s a rather extravagant and peculiar character. For those who are familiar with his background, his peculiarities speak as much of a bygone era as they do of himself. In today’s context, his persona and his obscure place in collective memory allows one to sense the passing of time and the change of the eras.

Pam, when you speak of being interested in the reconciliation with what has disappeared, do you also have cultural heritage in mind? And if so, can you briefly tell us what role cultural heritage plays in your current artistic explorations?

P.V.: I’m interested in both the tangible and the intangible parts of it. I’ve looked into the cultural heritage linked to my community (the Thai-Chinese diaspora), though navigating the depths of your own cultural history often feels like standing at the centre of a whirlwind, where emotions run intense and the subject matter is deeply personal. I’ve often looked for representations of this cultural history through different channels, though in pop culture there are a lot of stereotypical representations – usually exaggerations which I can’t find myself relating to. Within my family, discussions about our history were always minimal and cryptic. Even the Teochew language, one of the Southern Chinese dialects – native to my ancestors – was also not passed down. This absence of connection left room for imagination, prompting me to turn to the works of filmmakers like Edward Yang and Hou Hsiao-Hsien as sources of alternative histories for reimagining the Chinese diaspora heritage. For further context, both directors are Taiwanese, and some of the historical films they made, albeit rooted in Taiwan, delve into the societal and familial upheaval of the Chinese diaspora of the time. Interestingly, these events coincided with the period during which my ancestors relocated to Thailand. This paradoxical proximity, where I can view a cultural history from a distance and with a certain detachment while at the same time remaining intimately connected, profoundly influences my artistic approach and practice. I believe this resonates with both of your areas of interest. It’s fascinating how we can experience a connection to a different era and landscape, even feel a sense of nostalgia for it, despite not having personally lived through it, but through cinema. Could this be considered post-memory?

A scene of Yi Yi (2000) by Edward Yang projected on a broken screen. image taken at ‘Edward Yang: A Retrospective’, Taipei Fine Arts Museum

O.K.D.: It’s a funny coincidence that our correspondence would turn to post-memory, as for the past few weeks I have had a recurring dream where I could travel back in time through photographs. In these dreams, there was an album that let me choose a different time – the interwar period, the childhood of my parents, my own childhood. The key was to study the photographs closely and to capture all the details. As I woke up, I kept thinking about where this persistent need to remember or simulate the past was coming from. Could it be a sign of, as you say, post-memory, a need to forge an individual relationship with the historical and a personal past, always grappling with a sense of an unbridgeable gap? In any case, I believe that cinema, perhaps more than other media, can be considered post-memory. These artefacts, or even dreams of them, could serve as a means to rework the past and move on. I wonder: is it possible to become tired of constantly remembering, or is it our responsibility to make the narratives of the past relevant today again? Is constructive forgetting still possible or has it become a luxury in this digital environment?

P.V.: Surrounded by pervasive digital simulations, living wholly in the present seems elusive. In our era of post-memory, our effort resembles more a creative reinterpretation than a mere recollection. However, by revisiting and reconstructing the past through imaginative lenses, we have the potential to address the lingering traumas of previous generations.

The challenge lies in how we can respectfully carry forward their narratives without appropriating them, without drawing undue attention to ourselves, and without risking overshadowing our own stories. Maybe the answer lies within the realms of forgetting or deliberate omission. After all, forgetting is an inevitable aspect of life. Yet, there exists a distinct difference between actively choosing to omit something and allowing it to slip from one’s mind. It’s a paradox of sorts.

G.P.: Pam, when you speak of the lingering traumas of previous generations, what exactly do you mean? The reason I’m asking is because I’m curious to hear more about your cultural background, which includes family ties (subject to socio-political circumstances) that inspire your practice. Also, we often mention history in our conversation, but could you talk about the role of mythology in Thailand, which also plays a part in the formation of collective and personal memories?

P.V.: When I speak of the enduring traumas of past generations, I’m referring to the intricate historical forces that have moulded my cultural identity as a member of the Thai-Chinese diaspora, influenced notably by Confucianism and Taoism. A central aspect of this exploration involves recognizing the patriarchal oppression inherent in Confucianism, deeply entrenched within the family structure. These oppressive elements contribute to the generation and manifestation of some ghost stories that are told by my female family members.

To quote the words of Wasana Wongsurawat, a Thai historian who researches Chinese and Thai geopolitical affairs and whom I had a chance to interview, this is what she has to say about the connections between ghost stories and Confucianism:

“It makes perfect sense that female family members would be telling ghost stories because over 90% of Chinese ghosts are women, and it is like that because in the Chinese family structure, women are invisible; women don’t matter. Therefore, the untold stories in the family would be ghost stories, and they would be told by the female members. Telling ghost stories among female family members could be a useful tool for establishing solidarity among themselves.”

The ghost stories and mysterious tales passed down to me by my grandmother and mother follow a non-linear narrative pattern, seamlessly shifting and intertwining from one story to another. These narratives include enigmatic nocturnal sounds, the tragic tale of a night peddler who met an unfortunate end in a pond only to return to his family as a lingering fishy odour, and the captivating account of a fortunate cat that brought prosperity to a family business but eventually transformed into a cautionary tale. When we dissect the development of mythology, one can argue that it’s the passage of time that allows stories and household tales to gradually evolve into legends. In my view, these stories are in the process of becoming mythology, as they continue to accumulate layers of meaning and significance over time.

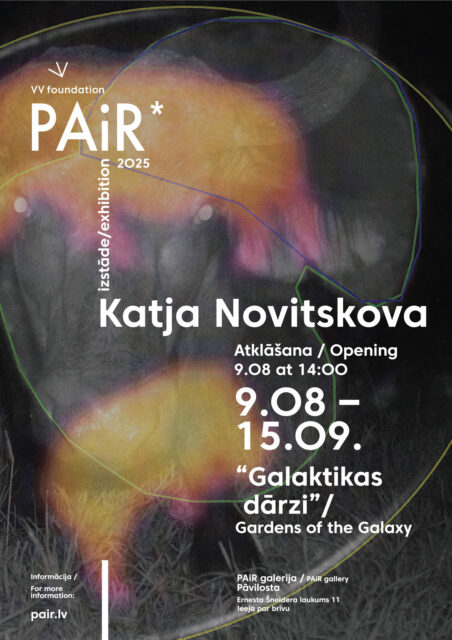

O.K.D.: When I think back to our initial meeting, it seems that the three of us bonded most strongly through sharing the mythologies of our cultures, various books, and illustrations of eerie folk tales. During your stay in Rupert residency in Vilnius, did you happen to find any parallels between Thai and Lithuanian mythologies, histories, experiences…? Could you also elaborate on the specific focus of your research here in Lithuania?

P.V.: Initially, I was drawn to fairytales and lesser-known myths as a means to immerse myself in an unfamiliar culture. I embarked on a research project at Rupert with a specific focus on “Ghost Tours,” which serve as a vehicle for connecting the urban environment through chilling tales of the city and the nation. However, it soon became evident that most of the stories shared during these tours were closely tied to figures of authority. It echoed the notion that history is often written by those in power; most of these narratives are centred around the construction of the nation’s identity. While I found this aspect intriguing, I wanted to delve deeper into the lesser-known micro-narratives and hidden stories. What I learned from our discussion was that what sets Lithuania apart from Thailand, however, is the limited culture of consuming horror movies; instead, folk tales take centre stage. These stories, interestingly, often serve as conduits for instilling fear within the culture.

Personally, I feel a deep connection to folk tales from the culture of storytelling in Thailand, where discussing ghost stories is a common practice. During evenings spent with friends, concluding our gatherings by sharing chilling tales of the supernatural is habitual. Thailand is full of ghost stories, and I sense that these narratives permeate the very fabric of the landscape, architecture, and the general atmosphere. What strikes me as similar upon arriving in Vilnius is the prevalent eerie aura that envelops the surroundings. This phenomenon seems less pronounced to me when I’m in Western Europe. I attribute this eerie feeling to the belief people have towards spiritual beings, which seem to saturate the place, leaving its imprint on the architecture and diverse landscapes.

Book found at the flea market near Kalvariju Market

G.P.: As Ona has already mentioned, when you spoke of the importance of Thai ghost stories and chilling tales during our first meeting, Ona and I were nodding as we both remembered the dark Lithuanian folk tales that were still a popular read in our childhood. Besides the Devil, one of the common protagonists, these tales include different spirits of nature, such as Thunder, the god of nature in a human form. It intrigues me that the feminine line is also prevalent in Lithuanian mythology. Laumės (a kind of swamp fairies) – other frequently encountered characters, intermediaries between the earth and the heavens – are also considered some of the most twisted and cruel creatures because of their irrational and unpredictable behaviour; for instance, their love for fun and dancing – the latter believed to be the cause of rain and storms – or their habit of stealing or swapping newborns for different objects such as brooms or straw bundles. I am also very curious how the mythologies and tales of different cultures and cities can resonate with each other, and how what seems surreal and peculiar can sometimes begin to seem self-evident and familiar, even strangely casual. Maybe it can be considered a form of collective imagination without defined boundaries, an ongoing and inexhaustible conversation that floats freely and is intensified by the most unexpected encounters.

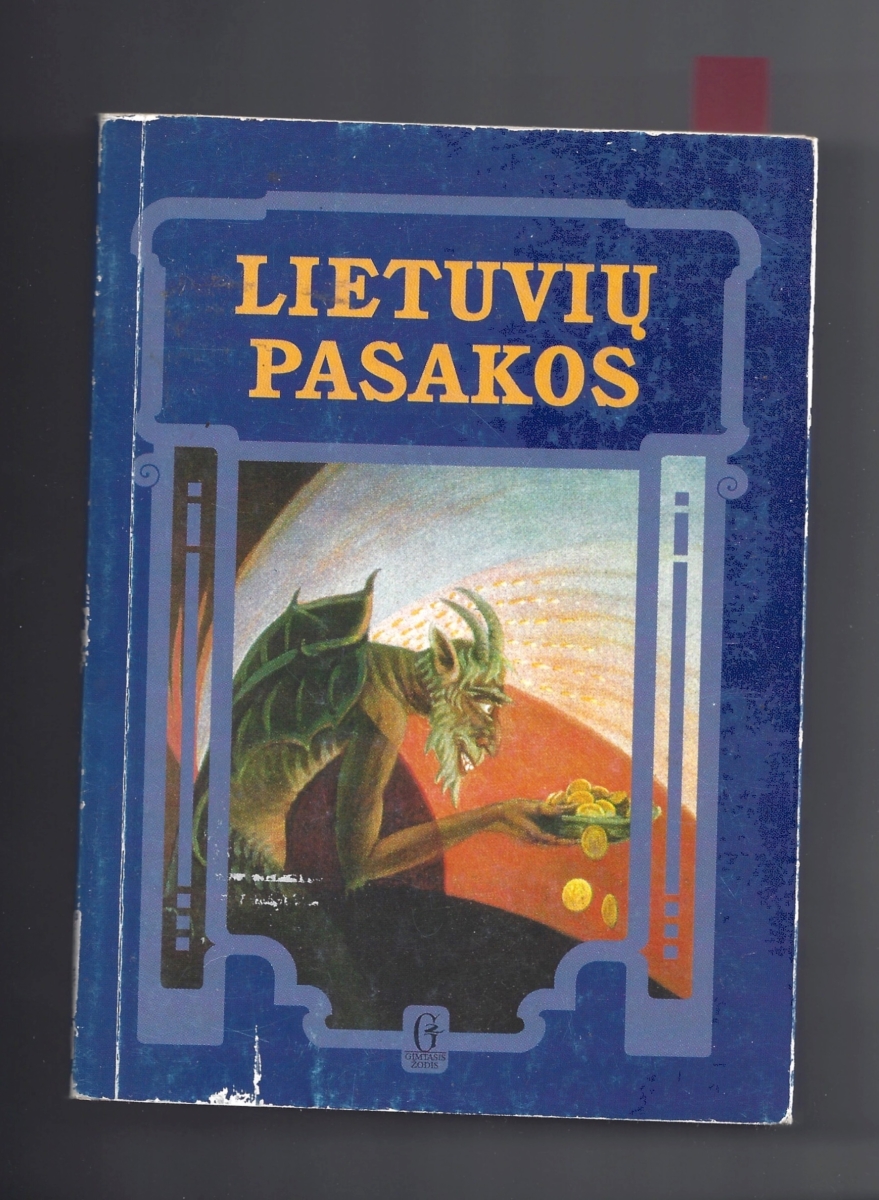

P.V.: It’s fascinating that you have mentioned Laumės. One of the tales about them actually sparked my interest in the manors located in an area believed to be connected to them. Among the places I filmed was Baltoji Vokė Manor. According to legend, the Vokė River region has multiple villages named Vokė, and there’s an intriguing story behind their proliferation. As local folklore has it, a long time ago, six sisters (or perhaps Laumės) with identical names resided along the Vokė River. They had a penchant for captivating lost travellers in the forest, ensnaring and enchanting many who had wandered into the impenetrable woods. Eventually, they grew weary of this life and decided to seek happiness elsewhere. Wherever these sisters settled, villages named Vokė sprung into existence.

I’ve heard from somewhere that true folklore is neutral. When it deviates from neutrality, it often arises from personal imagination, driven by either fear or an intense admiration for something. I’m not sure what to think of it, but somehow the aforementioned tale encapsulates this essence of neutrality; a genuine embodiment of folklore. It doesn’t bear the trappings of human-crafted stories and legends; instead, it epitomises pure belief, occasionally materialising as beings resembling women or animals, with no specific disposition towards authority or power.

Photograph of Baltoji Vokė Manor. Credit: https://zamkilubuskie.pl/biala-waka