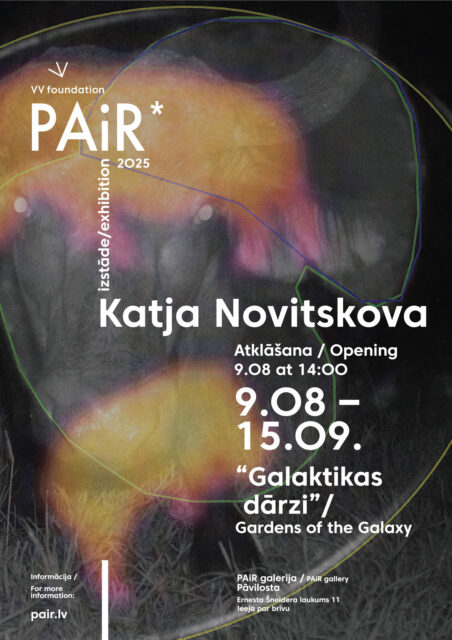

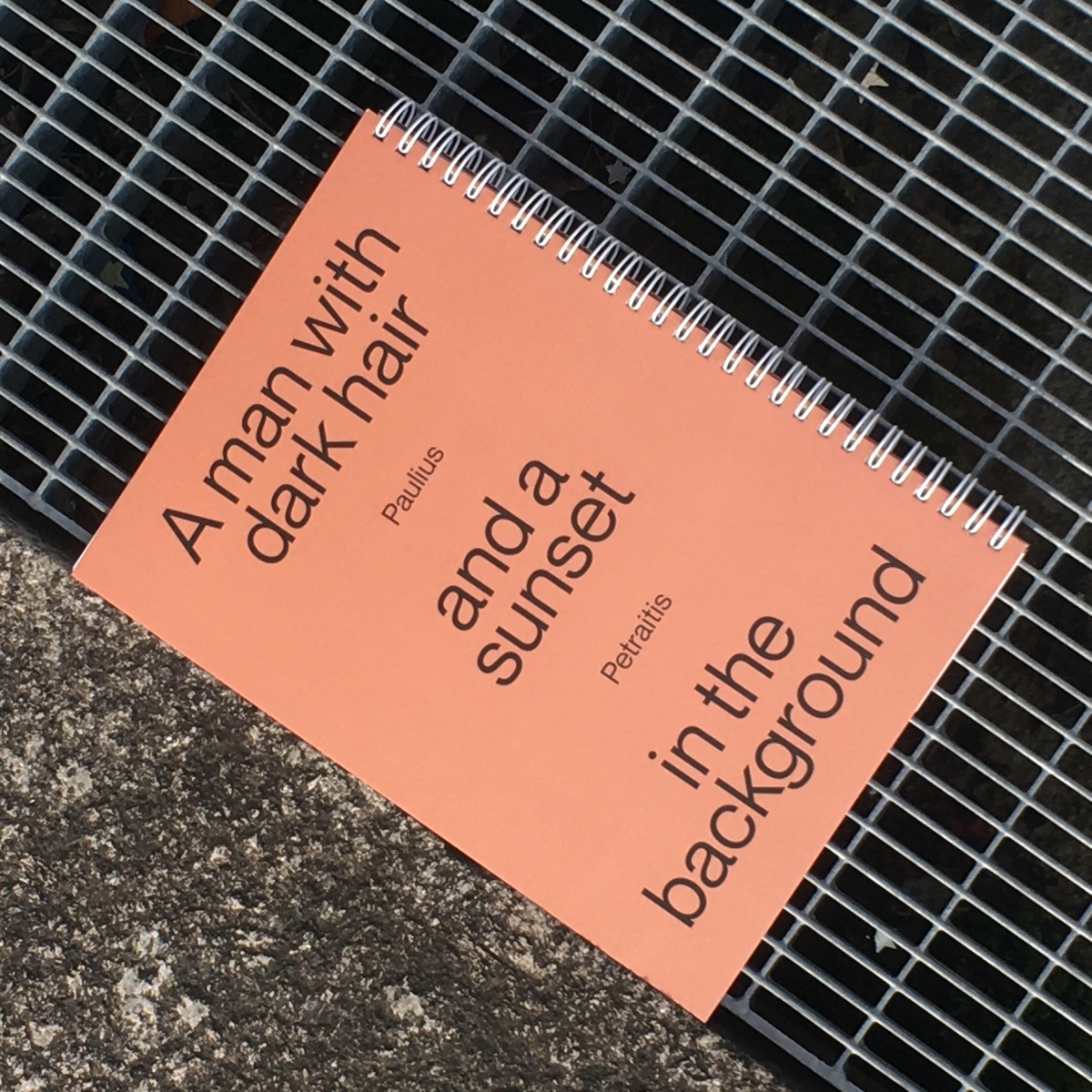

‘A Man with Dark Hair and a Sunset in the Background’ by Paulius Petraitis is a photography book consisting of a series of images taken with a Ricoh GR-2 camera, and then analysed with Microsoft Azure Computer Vision service between 2017 and 2020. Each image in the book also has two captions, the first being a description provided by the computer vision service when the image was first introduced to the project, and the second was generated just before the book went to press. Additionally, both captions include a confidence score, a number indicating the program’s confidence in the accuracy of the description it provided. The book also includes a poetic text by Monika Kalinauskaitė, focusing on (un)certainty in our private lives.

For the viewer and the reader of the book, at first glance the central intrigue is around the computer vision program’s ability to provide accurate descriptions, or to (poetically) fail. In addition, in comparing the first and the second caption for each of the images, the reader’s first instinct is most likely to expect progress, assuming that either the descriptions become more accurate, and/or that the confidence increases over time. Looking closer, however, for this particular set of images, it is not always the case; there are too many variables involved in the process of machine learning. But, come to think of it, does our own confidence increase or decrease as we learn more? Well, it can go either way.

The book is seemingly based on the playful interaction between the artist and the computer vision program. We have almost grown to expect something poetic to emerge from the inadequacy and inaccuracy of machine learning tools. This is evident in our endless fascination with all kinds of bots. Art especially is fertile ground for elevating these shortcomings, and often the tools are granted co-authorship in the process. Even though ‘A Man with Dark Hair and a Sunset in the Background’ does not discuss the machine as a co-author, I find it important that, as viewers and readers, we are aware of the fact that computer vision is, after all, a service provided by a company. Users have little specific knowledge of how the machine is ‘trained’, or in fact how it ‘sees’. This sometimes leads to a certain kind of mystification of ‘intelligent machines’. Discussing the term ‘artificial intelligence’ more specifically, Jaron Lanier and Glen Weyl point out in their article ‘AI is an Ideology, not a Technology’[i] in Wired how AI does not denote specific technological advances, and refers to the subjective categorisation of tasks that we consider intelligent. They write how this subjective categorisation is then used extensively in marketing, and I do think it is quite evident that this also shapes our attitudes towards technology in society and culture in a broader sense as well.

Paulius Petraitis, “a vase of flowers on a table, confidence: 0.5778592” / “a vase of flowers on a table, confidence: 0.5004501”. From the series “A man with dark hair and a sunset in the background” (2017-2020)

Nevertheless, looking at the results provided by image recognition software, I am always curious what data was introduced to make it recognise certain things the way it does, and to what end. In this, I also assume there is a kind of shared knowledge, that I have seen at least some of the same things ‘it’ has, beyond just the basics, like cats, dogs, apples, chairs, etc. I expect some sort of cultural knowledge, embedded by the people who compiled the necessary data sets, to also come through. To a degree, it should not matter much to me, the consumer: the process is relatively opaque, and I can only marvel at the output anyway. But it only does not matter to the point where it suddenly matters a lot: it is when human biases in data processing become evident, and produce a horrible result, like racist or sexist statements, where neutrality supposedly prevails. Often, incidents like these are brushed off as errors; but, taking into account the ever-present, although invisible, human factor in machine learning, it does raise the question, are these mistakes an error, or is it really a feature, an unwanted one, but a feature nevertheless?

The possibility of encountering recognisable cultural and social cues, assuming a shared ‘vision’, is perhaps not that far-fetched, considering how little distinction there is between public and private images today, and how both are used to develop image recognition technologies.

In addition to presenting its dynamics with the computer vision service, Petraitis’ book also contemplates how image and language are interlinked and operate in this (presumedly shared) world. While images and text, either in the form of captions or tags or indexing, go hand in hand, they are never fully equivalent. I always enjoy reading user-written image descriptions on Instagram; not photograph captions, but descriptions meant to make the app accessible to people who are blind or visually impaired, since they almost always provide a new perspective on how the user sees their image, and what they value in it. But what does accuracy mean in the context of this kind of highly subjective description? In a way, we are always trying to trace what others see, how they see, and what they know. In her piece ‘The Communal Mind’[ii] in the London Review of Books in 2019, Patricia Lockwood details her life with her mind constantly populated by internet memes, describing how online content permeates every aspect of her life, and how it becomes her way of relating to the world. In 1991, Star Trek: The Next Generation featured an episode where Captain Picard encountered a race that only spoke in metaphors. Instead of using language in its more conventional form, members of the alien race spoke, for example, in phrases like ‘Temba, his arms wide’, a metaphor for giving and receiving, or ‘Shaka, when the walls fell’, a metaphor for failure. This is not unlike how we have begun to think about memes and viral images today. I am probably not the only one who, having encountered a completely misplaced assumption about something, thinks of the ‘Is this a pigeon?’ meme, before being able to formulate any coherent thoughts of my own. In this kind of shared consciousness, at a particular moment, mental images like these can be extremely accurate; at the next, however, they may have already completely lost their meaning.

“A man with dark hair and a sunset in the background” book. Published by 6 chairs books & Lugemik, 2020. Photo: Tadas Karpavičius

Our confidence in identifying what we see indeed changes in time, as we grow increasingly distant from both our former selves and from a particular point in time. A friend of mine gave me a gift, a tiny jewellery box she had found in a flea market. The lid of the box is painted. The image depicts a girl in a long, Empire-style nightgown. Her hair is tied up with ribbons. She is sitting on the armrest of an armchair under a dim light, either a lamp or a candle, in front of a decorated fireplace, looking intently at a small, slightly glowing, rectangle in her hand. Handing the box to me, my friend said: ‘She’s looking at her phone.’ And despite the fact that the nightgown, the hair and the furniture in the little round painting evoked a time long past, I saw that the girl was, indeed, looking at a phone. The rectangle was too thick, stiff and reflective to be a letter, and held at too strange an angle to be a mirror; anyone who has ever accidentally opened their front camera knows this.

Just as we humans, for whom seeing is mostly a natural function, at least to a certain extent, have the ability to recognise social and cultural references, image recognition software also often struggles to identify historical images correctly. Furthermore, their ‘vision’, as it is based on contemporary images, becomes culturally situated in our time, and as we see in Petraitis’ book, a simple mango placed on top of a notebook suddenly becomes ‘an Apple computer’. In addition to creating a temporal lineage in image recognition of a particular set of images, ‘A Man with Dark Hair and a Sunset in the Background’ also highlights our own expectations and preconceptions regarding image processing, as well as the cultural situatedness of images. Although we know that both language and images are slippery, it is sometimes necessary to witness how they get pinned down by the weight of their own temporality.

[i] https://www.wired.com/story/opinion-ai-is-an-ideology-not-a-technology/

[ii] https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v41/n04/patricia-lockwood/the-communal-mind