This conversation took place in the summer during the rather peaceful time after the first lockdown had finished and before the start of the second one. Now, as various art institutions are moving their activities into the virtual space, art objects are becoming increasingly difficult to grasp; and yet, on the other hand, the artists’ working processes, their ideas, means of cooperation, resources, organisational principles and everything else, which usually remains somewhere behind the objects showcased, are now coming to the fore. This conversation is about exactly that: about the ever-slipping-away materiality of a work of art, and how it is experienced, as well as about how it resists extinction in the constantly growing virtual sphere. Moreover, it is a conversation about painting, and its dependence on technology, and on other, completely unrelated, fields.

Edgaras Gerasimovičius: What areas have you been interested in recently?

Gabrielė Adomaitytė: My main area of interest is information, the information-age which we are currently living in. I am interested in the post-truth phenomenon and related topics, particularly in the relationship between documentary and the imaginary; in the role that archives play in creating history; in technologies of memory, the influence of digital archives on the collective memory, and the impact they have on the human identity. My creative work since 2016 has been focused on archival practices and problems related to it, such as visual research on material collections of human knowledge, and attempts to work out how the conservation of ancient artefacts is carried out in order for history to be created. In my opinion, topics concerning how the past is expressed through matter have affected me personally, first and foremost because I have tried to recreate certain photographic memories about people and places which were no longer there. Each of my series of paintings was created through a personal connection with the materials used. In 2018, I created a diptych that I dedicated to my parents (‘Dreams & Desires’, 2018), which made me realise that all my projects are tied together by a continuous investigation into the echoing past, through which I have attempted to shorten the distance between myself and the immaterial information media inscribed in our collective and personal memories. My visual material, the basis of all my work, is made of clues and traces. What’s more, after moving to the Netherlands, I’ve encountered decolonial theory, and visited a couple of exhibitions devoted to it. It fascinates me, and has acted as a stimulus to investigate archiving processes, and problems in preserving the past. I’ve recently been spending more time on books at the Ritman Libarary in Amsterdam. This is a private collection consisting of more than 23,000 publications on occultism, mysticism, gnosticism and alchemy. I often go to Teylers Museum, the oldest Dutch museum, in Haarlem, where, in the Oval Room in particular, which has a broad collection of minerals, one can even find the summit of Mont Blanc. I am currently trying to understand these places, in order to use the emotional connection I have with them in my own creative work. In the future, I’d like to work with algorithms. That’s one of my goals for the near future. I’m planning a trip to the Sitterwerk Library in St Gallen in Switzerland, for which a special search algorithm has been created: it intertwines subjectivity and coincidence in a dynamic structure, which functions as a particular organisation of knowledge.

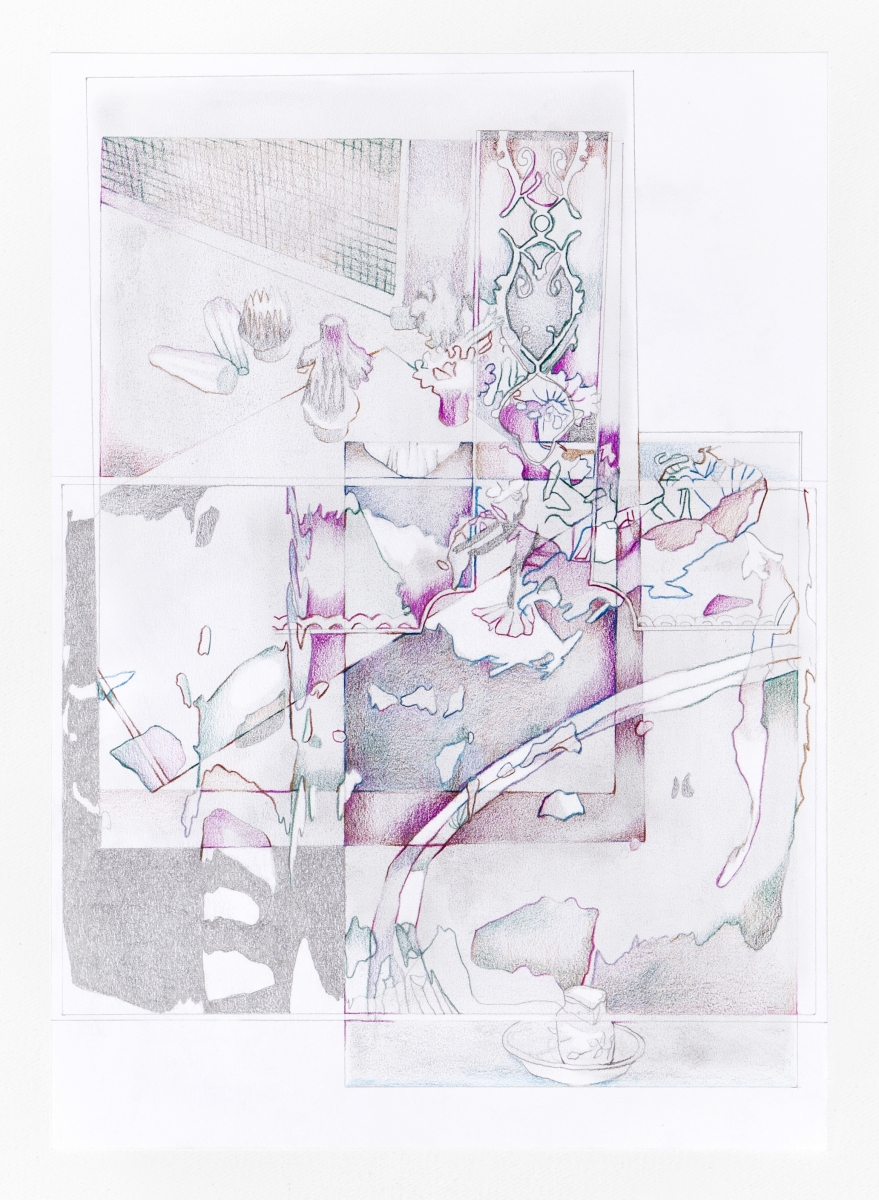

Gabrielė Adomaitytė, ‘5 Minutes to Midnight’, graphite and colour pencil on paper, 29.7 x 42 cm, 2020

EG: The first time I saw your paintings in real life was in 2018, at the JCDecaux Prize exhibition ‘Dignity’ (in Lithuanian ‘Orumas’). That was the diptych you just mentioned, ‘Dreams & Desires’. The main motif in the paintings was a white, partly torn net, which appeared to be covering a black canvas. This motif is present in your other works as well. At times, it seems to be independent, a separate element; at other times, it functions as a background for the main pictorial event to unfurl. Can you tell me a bit about this motif?

GA: Firstly, I should mention that I planned to take part in the JCDecaux Prize exhibition with a completely different piece. I was working on it at the time of the application; however, after finishing it, I decided not to send it to the main exhibition. At that time, I had a bunch of VHS tapes from my family home in my studio in Amsterdam. My father had filmed me from the day I was born to the day he died. I knew that for the JCDecaux Prize exhibition I wanted to create paintings based on family material, and I wanted to let them take me wherever they would. Before starting to paint them, I took all my things out of my studio, and kept only what I had brought from Kaunas. I watched the VHS tapes on an old television set. At that time, the mere representation of an object on a canvas wasn’t enough for me; it was important to move from copying an object’s shape to a direct, actual ‘footprint’ of that object. I wanted the painting to be a true monument to the object.

This unsent painting was the first time I used the net motif; but in the diptych ‘Dreams & Desires’ it was transformed into a somewhat generalised experience of that net. The very process of painting the diptych was truly performative, since I covered the canvas with an actual net: I would paint in its holes in order to give the image a feeling of depth. ‘Dreams & Desires’ is a holey visual wall, which opens or closes according to the position of the viewer in the exhibition space: the distance from the painting determines how much of the net itself and the view behind it (dis)appears. It is as though the net in my paintings connects modes of virtuality and the tangible reality.

My aim to get closer to an object’s charge in ‘Dreams & Desires’ revealed itself from a different angle too, and I haven’t spoken about it publicly before. This diptych is dedicated to my parents: while I was painting it, I was wearing my father’s jacket, and together with the sonograms (my mother is a doctor), these objects directly affected my painting. This has been by far the most personal piece of mine.

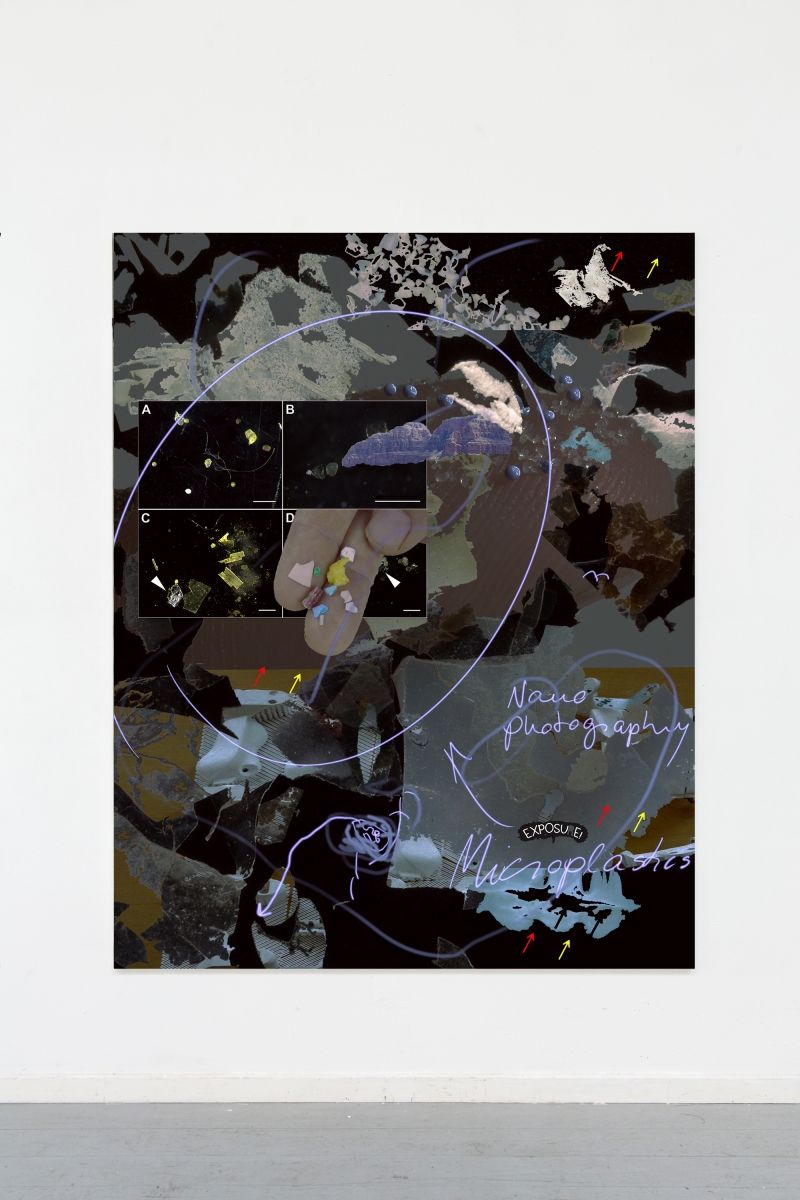

EG: Looking at your paintings, one might think that the investigation of the past and your attempts to understand it through the archives are first and foremost a journey through a noisy, visually cluttered, dense ether. That is most evident in your latest works, such as ‘Overdrive’ (2020). The title of the piece suggests an object which has surpassed its normal limits of activity. In your work, this surplus is augmented by the contrasting elements of painting, and the layering, which creates a specific, tense, yet simultaneously orderly and thought-out, visual drama. Can you say a bit more about this layering, and about the noise?

GA: I created ‘Overdrive’ by employing visual data from an actual material archive, which consisted of a variety of Soviet devices. One of them was a vacuum cleaner called Raketa (or ‘rocket’). I transformed it into a cyborg, rather than anything resembling a domestic appliance. In my paintings, an image is created both by adding and subtracting information. And also by employing different tools, with a paintbrush or aerograph, by wiping off the paint, and sometimes through the use of a completely improvised tool, such as a broom … Although my painting process is alive, and, of course, guided by intuition, the image I produce initially appears clearly in my head, and I always make precise sketches beforehand. The works I made this autumn were made exactly in that way. Today, the process is shifting from the physical space to a digital one, and vice versa, while the final result and its .jpg are barely distinguishable.

I find it interesting to look for tension between abstraction and concreteness. Therefore, the motifs from which I start my paintings often dissolve fully, becoming almost unrecognisable. At times, they end up as titles, or they become clearer only if you look at the whole set of paintings, and not at a single one separately. There are only a few dimensions of canvases that I use; therefore, the paintings are like separate screenshots that a particular topic, or story, comprises. Equally important to me is multi-dimensionality, which allows different motifs and techniques to coexist within the same picture. That is most obvious in one of my pieces called ‘Screen #001’ (2018), in which I present a few different motifs, merged into a single screen experience, consisting of info tabs and pop-up messages.

When I paint, I intuitively attempt to find and leave out the golden zones on to which our gaze normally falls. All those golden rules and models for order seem very fragile on an irrational level. I want to point out that I started working from photography when I was 13 years old, and I also took up academic drawing for six years. Perhaps because over time I got used to the rules of representation, it seems normal to me for them to be broken. Without harsh contradictions, it can be shown that the rules do not solve the bigger picture. The Cubist way of thinking is important to me, because it presents a complex view of the representation of reality and time. For me, the bricolage of fragments is an attempt to capture that dense ether that does not comply with the usual rules of representation. Painting with elements of abstraction fascinates me, because it allows us to experience a state of surplus, and to connect all heterogenous sources. Talking about my current painting process, I’ve been playing with the finishing touches: I’ve recently been taking my time, and extending the moment of finalisation quite a bit.

Gabrielė Adomaitytė, ‘Skeletons of Search Engines, study’, digital painting, variable dimensions

EG: Last year, you had the solo exhibition ‘Traversing Discrete Loci’ at the Annet Galink Gallery’s project space The Bakery. At the core of this exhibition was the Museum of Clothes. If I understand correctly, the vacuum cleaner that you mentioned earlier is from this archive. Tell me, what is this Museum of Clothes?

GA: During my residency at Rupert in Vilnius last autumn, I gathered information about an archivist who set up a museum of the Soviet heritage in his home not far from Kaunas. He called it the Museum of Clothes. The title is a link to the now-destroyed Drobė (or ‘canvas’) textile factory in Kaunas. For almost eight years, I followed his YouTube channel, where he shared his documentation of contemporary Kaunas from a Soviet perspective. After visiting this rather personal museum, I wrote a couple of articles, and made a corresponding series of paintings; the visit made me feel I was travelling in time. The calendar on the wall there was from 1979, and the founder of the museum told me that it was exactly the same as the 2018 one; therefore, it was being used for a second time. The series I made was then presented at The Bakery. The exhibition title, ‘Traversing Discrete Loci’, points to an ancient Greek method of remembering things, loci, or the so-called memory palace, in whose imaginary rooms, in your personally created mental images, you position certain information. I’m trying to find a way to employ this mnémotechnique working with my own material.

EG: What skills outside painting itself do you need to create one of your paintings? This is a behind-the-scenes question about your creative practice, but it is also a question about your relationship with the painting tradition. What do you think is the state of painting today?

GA: I always try to make digital sketches for my future works. And that has hardly anything to do with painting itself. Digital drawing and modelling have more to do with the search for material, with the selection, study, sorting and recycling of motifs, and that requires a knowledge of fields other than art theory. Therefore, a field that requires specific skills is digital image archiving; the preparation of a sketch is equally important to the painting itself, although the qualitative processes differ. The ability to work with digital visual material is relevant in contemporary society in general: it is an important part of the attention economy.

My interest in archives was sparked not by painting but by other things. Other projects of mine lean towards theory. I am extremely interested in the development of techniques of gathering and enacting information, in institutional and personal collections, and the personalities of collectors. Painting goes together with this fascination of mine; yet I cannot ignore the fact that there now exist paintings created by robots, and, generally speaking, that now everything is hyper. For example, the works of Avery Singer, Parker Ito, Jamien Julian-Villani, Petra Cortright, Charline von Heyl, Laura Owens and Jacqueline Humphries are permeated by the experience of our contemporary digital culture. Therefore, to answer your question, I must simultaneously consider how I would expand the limits of painting, which in itself isn’t a question about painting any more. In my opinion, there are two ways of looking at it today: on one hand, painting is on the side of fiction; and in this way it is different from the exact representation of reality, which is employed by the new media art, for instance; and perhaps it is a negative aspect of this practice. I remember a studio visit with the curator Maria Lind, and our conversation about my interest in archive practices. She suggested starting off with the materials I initially possessed, and then picking the right medium for a work, as if painting could not be used to transfer information in that way. However, I believe that my goal as an artist is completely different. I try to employ information as though it was not to be considered any part of the social or political reality. What I am trying to say is that painting can provide a critique in its own specific way, although perhaps not as accurately as other artistic means, since it is not as involved in all that.

In contemporary art today, I see painting as one of the most interesting media, despite all the criticism it gets. Post-humanist or post-performative painting, as described by Marie de Brugerolle, sustains vitality, due to the process of its creation. Isabelle Graw wrote about it in her book The Love of Painting. It is quite different to other practices which have language at their idea-generating core. The intuition and visuality of painting and other process-based creative practices are not limited by the verbal sphere, so they retain their efficacy. Painting has acquired many technical advances that have the potential to affect the viewer more than the digital image, since it manages to move the focus from the screen to the more physical experience of an image.

Gabrielė Adomaitytė, ‘Two files of the same title in one folder (Win7)’, graphite and colour pencil on paper, 29.7 x 42 cm, 2020

EG: You mentioned that your creative practice began with photography. What programs or tools do you currently use in your work?

GA: At the age of thirteen, I attended a photography course, so, to be precise, I started from analogue photography. Having progressed to a digital camera, I learned to use Adobe Photoshop, which is one of the main programs for me to this day. In the studio, I work with a Wacom drawing pad. I have a couple of scanners, a printer, a projector, and various programs from the Creative Cloud. Sometimes I print certain parts of a painting digitally, or I use a laser to cut text out of stick foil. Since I create in different media, and use variable dimensions, I have the chance to transfer digital images on to the surface of a canvas. Attracted by the extended reality and the possibilities of printing with aerograph, I try to use it in my work. I am currently spending a lot of time learning how to use Cinema 4D: this program opens up completely new creative horizons.

Because of my upbringing, medical equipment has had a great influence on my creative work as well. My mother is an obstetrician-gynecologist: we used to experiment with ultrasound. I had access to this device thanks to her, and sometimes she would send me sonograms, for example, of her arm. I even have a sonogram of her heart. I also use MRI and encephalography, which I have encountered myself while investigating migraines, as well as ultrasound test photographs. This material for me is an expression of all the meaningful technical mediators of today. Before, while studying sculpture, I used to work with scanners. I needed an additional step towards a particular topic, towards an image. Certain qualities of performative image would appear: at the time they were important to me, because they would change my connection to the objects that were about to be depicted. It is thrilling that while working with digital technology and painting in parallel, the possibility of collecting and re-contextualising a wide sphere of information appears, in which contradictions or anachronisms bond, and therefore create new systems for knowledge, new conditions for radically immersive experiences, and multi-dimensional global virtual reality representations, to appear.

Gabrielė Adomaitytė, ‘ORZ-7’, graphite and colored pencil on paper, 65 x 50 cm, 2020

Gabrielė Adomaitytė, ‘Controlling the Trolleybus’, graphite and colour pencil on paper, 29.7 x 42 cm, 2020

Gabrielė Adomaitytė (b. 1994, Kaunas, Lithuania) graduated from the Sculpture Department at Vilnius Academy of Art in 2017. She currently lives and works in Amsterdam, where, until the spring of 2019, she was an artist in residence at De Ateliers. By constantly questioning the possibilities of painting and the problems of visual representation, the artist investigates information systems and the collision points of the digital and actual matter in various archives. Adomaitytė’s work has been shown in solo and group exhibitions in Lithuania and abroad: Arti et Amicitiae (Amsterdam, 2020), Swallow (Vilnius, 2020), Annet Gelink Gallery (Amsterdam, 2020), ‘De Ateliers’ (Amsterdam, 2019), the Vartai gallery (2019), and the Contemporary Art Centre (Vilnius, 2018).