Queer Histories from the Baltic Region presented innovative research on queer cultures and artistic practices, highlighting the rich history of gender and sexuality discourses in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. The programme – held at Auto Italia in London and the Edinburgh Art Festival in 2024 – aimed to broaden the understanding of the conditions faced by queer-identifying individuals in the region. It sought to provide a more nuanced perspective on queerness, moving beyond the dominant narratives that often focus on the US and UK. Here, curator Milda Batakytė speaks to artist and writer Sean Burns about the development of the programme, which contained exhibitions, performances and discussions. Batakytė is the Exhibition Curator of Auto Italia, London.

Sean Burns: Let’s start by discussing the origins of the Queer Histories from the Baltic Region programme.

Milda Batakytė: Yes. I suppose the whole premise of the project was to present the complexity of the LGBTQ+ experience in the region and relate it to the broader world. I don’t think it is healthy to approach queerness in a singular way, so I wanted to demonstrate a few examples of those complexities elsewhere.

SB: Yes. And it’s obviously never going to be a total picture.

MB: Yes, exactly. It all started with Karol Radziszewski’s exhibition ‘Filo’ (2024). I felt it was important to show Karol’s work in the UK because his project Queer Archives Institute has never been presented here before. He is among the very few Polish contemporary artists who has been working around the subject and looking at the queer experience. There are fewer artists in Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia openly contending with queer issues. Being in London, I’ve registered a lack of discourse in the Baltics because we are talking more openly about queerness here.

SB: A kind of comparison.

MB: Yes. The other impetus was emphasised by russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. I recognised the influence of culture as a soft power that can enhance the recognition of a nation-state, region or cultural identity.

Coming from Lithuania, a country that was part of the Soviet Union for such a long time, experiencing the invasion of Ukraine was shocking for me. It made me think about how a curator can respond and create soft power with a small exhibition. So, it’s sort of like creating several layers.

SB: Yes. What was attractive about Karol’s project?

MB: Karol’s research addresses so many different characters and histories, both before, during and after the Soviet occupation. I was in conversation with colleagues from the Baltics, some based in the UK. We all felt compelled to tackle the same sort of issues.

There were shared notions of needing to reckon with the trauma that the Soviets left. We observed that very few people had worked on that trauma since that period. So, since the 1990s, when Lithuania became independent, let’s say, nobody had addressed that trauma, and nobody has paved a new way for us to talk about the culture in this region or queerness or anything else that exists within that.

SB: Yes. It’s so recent, really.

MB: It’s so recent—like 34 years—so it just felt important. It felt important to process that for myself, my friends, peers and colleagues in those countries. We organised three events, two at Auto Italia in London and one during the Edinburgh Art Festival. We decided to invite people whose work focuses on direct action, who participate in different organisational and artistic interventions, to discuss the mentality and the perception of queerness in those regions.

It was remarkable because audiences heard Agnė Bagdžiūnaitė from Lithuania, Konstantin Zhukov from Latvia, and Heinrich Sepp, otherwise called Helgi, from Estonia. All of them have such different practices, but they had the opportunity to compare their experiences.

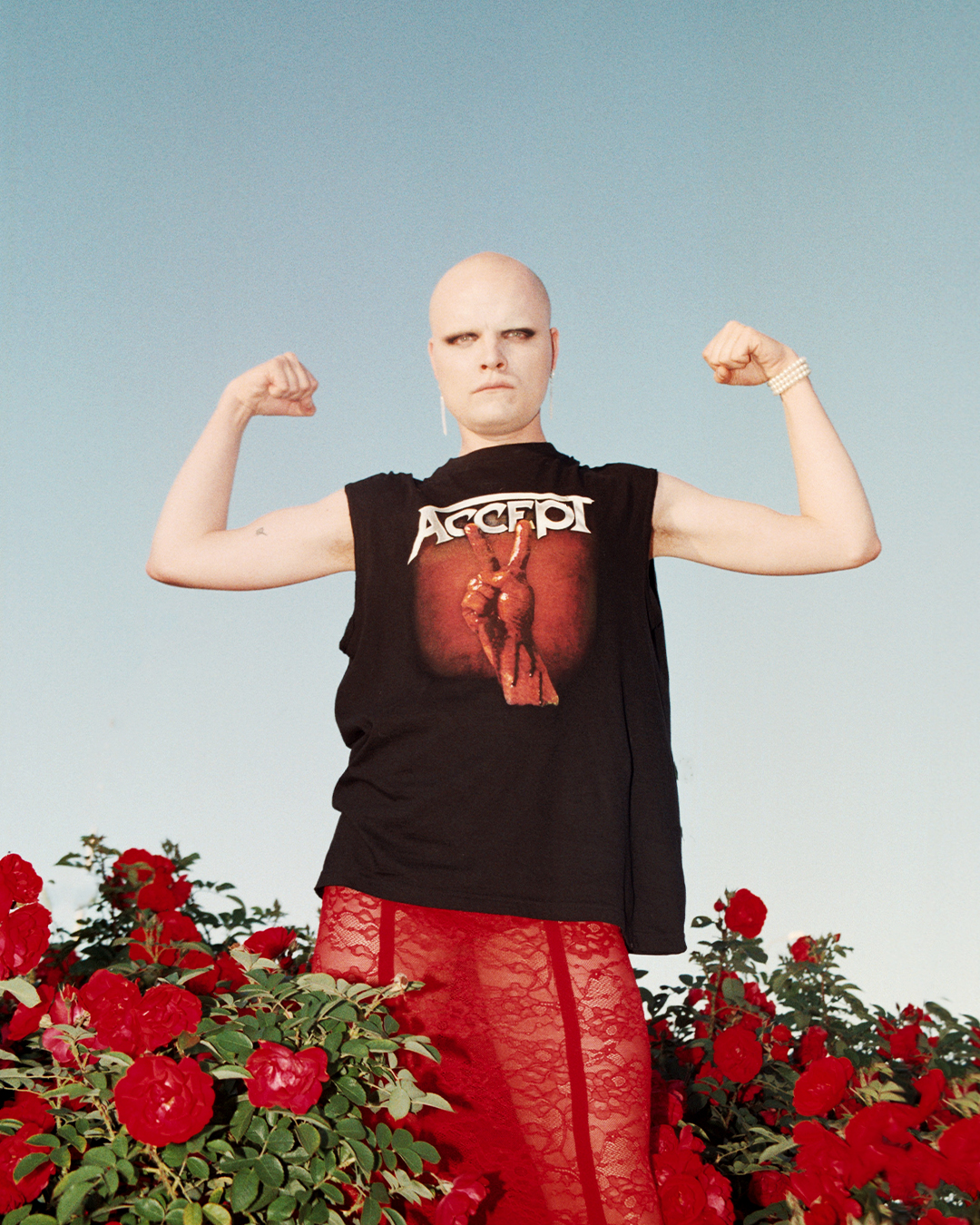

The second event was Gregor Kulla’s performance, Recital (2023). Gregor works specifically within the classical music genre. They are a classically trained oboist interested in revolutionising that world. Gregor presented this wild performance, which intersected with a drag performance of oboe and electronic music.

SB: It was like a kinky, cabaret oboe.

MB: I was looking at Gregor’s legs, and they were shaking loads because they were wearing these huge high heels. It was terrifying.

SB: It’s great that that happened here.

Rectial, 2023, Gregor Kulla. Kanuti Gildi SAAL, Estonia. Courtesy the artist. Photography: Alana Proosa

MB: Yes. So, that’s what happened in London. In Edinburgh, we invited Agnė Jokšė’s performance Lezbynai (2020). Agnė is a Lithuanian performance artist who works extensively with the written word. Their research and practice are related to activism. If I’m not mistaken, Agnė was also one of the first people to talk about how the Lithuanian language is gendered. It’s such an old, incredibly rigid language. So, it’s interesting how Agnė addressed that. Lezbynai comes from the name of a district in Vilnius (Lazdynai – Ed.). This area is notable for its quintessentially Soviet architecture. It’s a place which feels like a concrete panopticon.

SB: Right. So, it’s residential.

MB: It’s a residential area. There is nothing much around apart from these tower blocks, and they’re all concrete, and they’re all circulating around each other. The text that Agnė prepared and performed talks about her experience growing up there as a queer person and interacting with other queers within that context. And it’s an incredibly gentle and subtle performance.

SB: In the accompanying statement, you mention how LGBTQ+ cultures and rights are still largely underdeveloped discourses within the Baltic states. Could you discuss some of the factors involved in preventing a discourse from flourishing?

MB: I think, firstly, it’s cultural. During the event at Auto Italia, Agnė Bagdžiūnaitė discussed how there was a brief period of freedom for queer magazines and similar publications to flourish during the transition between the fall of the Soviet Union and the formation of Lithuania, roughly one to two years.

SB: This is early 1990s?

MB: Exactly. Early ’90s. People were thirsty for freedom, so they talked about allowing diversity to coexist in one place. Over time, whether due to being part of an oppressive regime for an extended period or some other universal cultural element, certain rigid observations and cultural prejudices have resurfaced and been reshaped in various ways. After a very short period of talking about it, and the relative freedom and liberalism in the ’90s, it slowly became essentially taboo.

SB: So, old prejudices re-emerged.

MB: Yes.

In Conversation: Agnė Bagdžiūnaitė, Heinrich Sepp, Konstantin Zhukov, Queer Histories from the Baltic Region, Auto Italia, London, 2024. Photographer: Anne Tetzlaff

Queer Histories from the Baltic Region, Auto Italia, London, 2024. Photographer: Anne Tetzlaff

SB: It reminds me of Spain after Francisco Franco died. There was this scene called Movida, which is a fashion-art movement where people enjoyed their freedom. And then you still had insidious reactionary ideas beneath the surface.

MB: It almost feels like once people lose this enemy, they then start looking for something to focus on and start creating enemies among themselves.

SB: And I guess you’ve got this sort of religious prejudice that’s baked into the culture and things like that.

MB: 100%. Religion is also a considerable influence. Karol mentioned that even today, churches in Poland, particularly in recent years, have gained considerable influence due to the far-right government that was in power between 2015–23. So much of the prejudice comes from the church as well. Lithuania and the Baltics are known to be historically pagan countries; Lithuania was one of the latest countries to turn to Christianity.

SB: Oh, really. That’s interesting.

MB: But despite the paganistic prehistory, Christianity is still rooted in the culture nowadays.

SB: Yes.

MB: We are generally seeing the rise of far-right politics across Western countries. Central and Eastern Europe are the same. All the panel participants mentioned the anti-LGTBQ+ movement. If Pride is happening, it’s typical for a massive far-right march to occur on the same day, which is incredibly intimidating. And other intimidation tactics are also used against people engaging in these discourses. Kaunas Artists’ House, which organised a series of events around queerness, queer histories and feminism, has received a backlash from local authorities. Or, Emma, a social club, a gathering place that Agnė also co-founded. It’s often physically attacked, with windows getting smashed and things like that.

SB: So, it’s both about the relationship with the funding, certain local people and the culture that they’re immediately faced with. It’s structural and about the reception of their activities.

MB: Yes. It really feels like a systemic cultural oppression now in that respect.

SB: And, in a way, I think that the people that spoke, who you’ve mentioned, were emboldened as well by that. Of course, and there’s a sort of resilience that we can come on to talk to.

MB: Yes.

SB: My next provocation was whether you wanted to highlight specific people, organisations and practitioners who are doing that work. Giving people a shout-out might be good. Maybe there’s a risk in doing that. I don’t know.

MB: I would particularly like to mention a Latvian activist, journalist and author, Rita Ruduša, an incredible example of somebody who has actively spoken out. Also, Lithuanian author Artūras Tereškinas was a very influential figure for me personally.

Again, somebody who has written about, firstly, women’s rights in Lithuania or the history that traces feminism in the country before. We can’t make assumptions that the situation was terrible only under the Soviets because it’s not necessarily always the case.

Heinrich Sepp, 2020. Courtesy the artist. Photography: Kristina Kuzemko

SB: Oh, yes. Right. There isn’t a clean cut, necessarily. I wanted to talk about Karol’s exhibition a bit more. Specifically, I was interested in the newspaper, the archival kind of stuff. To benefit people who might not have seen the show, can you just talk a bit about Filo magazine (1986–89) in its early years, and its place in the exhibition?

MB: I need to step back in history to create an understanding of where Filo stood when it was established. In 1932, in Poland, homosexuality was decriminalised, which was an incredibly progressive move for that period across the whole Western world at least. And later, when Nazi Germany occupied Poland, they overturned it and then later the Soviets disregarded this law.

And despite overturning and ignoring it, it was the relatively relaxed social attitudes towards queer identities in Poland compared to other Eastern Bloc countries in the 1970s and ’80s that allowed Filo to exist.

SB: Right. I see.

MB: So, Poland belonged to the Eastern Bloc. In the 1980s, they started an operation that was called Operation Hyacinth, which essentially collected information about every single queer person across all of Poland. They used that information to intimidate, blackmail and arrest people across the whole country. Ryszard Kisiel, who was an activist at the time, knew, in many ways, homosexuality had not been historically criminalised.

He understood that he held the power, essentially, if he was not scared of being intimated or presented publicly as a queer person. So, what he did, with a group of his friends, was throw these parties where they would dress up in wonderful homemade outfits. They would do photo sessions that were incredibly flamboyant and very often perhaps reference early 20th century’s French cabaret culture.

SB: Yes. It’s got a kind of 1920s cabaret vibe.

MB: Yes. And the group held these parties where these photographs would also be showcased. They didn’t hide these photographs, which, in many ways, would be incredibly intimidating and dangerous for many people.

SB: Yes, of course.

MB: To note, as well, in other Eastern Bloc or Soviet countries, you would literally be imprisoned if somebody caught you with these photographs.

SB: So, were they protected by the historical lack of criminalisation?

MB: Exactly. The group also decided to create Filo magazine to distribute information about legal rights, the HIV/AIDS crisis, and any other relevant community information. So, it was like a bulletin where you got this helpful information, and then you obviously would get some gossip, cruising and dating information.

SB: I guess there’s something about the way it was queer. Because it was playing with ambiguities, right? It wasn’t a gay porn magazine. And playing with notions of gender. There’s something about how it was ambiguous that was also quite clever.

MB: Yes. They didn’t have the same understanding of queerness as we do today. They used a different vocabulary and had their own ways of understanding and advocating for themselves and their rights. However, their behaviour was much more complex than that.

SB: I wanted to talk about the kind of relationship this material has had with the UK, your experience of touring it, people’s relationship with it, and whether there have been new unities formed around it. What has been your experience showing this material?

MB: I feel there is very much DIY, face-to-face things happening across the Baltics in terms of activist organising. It’s very hands-on.

SB: Filo really captured people’s imagination. It shows that you just take something, cut it out, write something, photocopy and distribute it by post or in person. There’s something matter of fact about it.

MB: There is a pragmatic element in building a close community.

SB: And responding to a need as well.

MB: And responding to a need, especially. I felt people who participated in the events were reminded, ‘Oh, I just actually can do it!’

SB: Yes, I can take politics into my own hands.

MB: Yes, exactly.

SB: Even on a small scale.

MB: Yes. I think politics in this country (UK), the way I observe it, is subjective. It almost feels like you don’t need to ‘do’ politics apart from voting. Many people don’t necessarily seek to execute their rights in any other way on a smaller scale, community-focus way.

SB: How about in Edinburgh? That’s a different context from London again.

MB: The feedback that I received was quite similar. Agnė Jokšė presented a context in which queerness both felt alien and relatable in many ways. It was so beautiful. A couple of people approached me and said, ‘Oh, yes, I just was imagining another place somewhere in Edinburgh or Glasgow, a similar weird architectural construction, where perhaps I had my first kiss.’ It felt like very transportable content.

SB: And people relate to that sense of alienation, especially queer people.

MB: I really appreciate how Agnė approached this subject. They handle queerness, language and history from that region in this very traditional writing and performance sense, and it’s just incredibly powerful.

SB: Yes, totally. And I guess there’s this question about the future, what happens with this material, and the kind of energy that the events have brought together. Do you have a sense of that, or are there any things planned?

Agnė Jokšė, Lezbynai, 2024. Auto Italia, London and Edinburgh Art Festival, Edinburgh, Scotland. Photographer: Jules Lacave-Fontourcy

Agnė Jokšė, Lezbynai, 2024. Auto Italia, London and Edinburgh Art Festival, Edinburgh, Scotland. Photographer: Jules Lacave-Fontourcy

MB: When we started doing the series of events, my friend, Adomas Narkevičius, a curator, with his colleagues Inga Lāce and Rebeka Põldsam, also opened an exhibition ‘We Don’t Do This’ at MO Museum, Vilnius, about queer histories, which was wonderful.

SB: Were you aware of that?

MB: I knew Adomas was working on something but didn’t know what it was. But I think these sorts of moments of conversations and exposure are important so that they ingrain into people’s consciousness and memory. It enables it to become an everyday discourse. I think the next step would be just to continue doing events like those I’ve mentioned. We’re always so focused on the UK/US understanding of queerness, it’s healthy and important to consider different perspectives. I want to extend thanks to all the wonderful participants and partners, Editorial (Vilnius), Kim? (Latvia), Center for Contemporary Arts (Estonia), Edinburgh Art Festival (UK) as well as the Baltic Culture Fund and its team for their generous support.

SB: I also think specificity is important. When I read through the things you sent, I felt this impetus to not think about the region as this one nebulous thing, to say that there are conditions that affect these countries, but within these conditions, there are very specific reactions and very specific cultures.

MB: Yes, precisely.

SB: And I think acknowledging specificities is an important aspect of this as well as nurturing the kind of resilience that comes from recognising similarities.

MB: Yes, completely. Couldn’t have said it better.

Rectial, 2023, Gregor Kulla. Kanuti Gildi SAAL, Estonia. Courtesy the artist. Photography: Alana Proosa