Vilius Dringelis is a young designer who is involved in a broad spectrum of activities. He creates conceptual design objects, and graphic design for books, catalogues, posters and exhibitions. Vilius’ creative work has been recognised both nationally and internationally. And yet this conversation is not about his achievements or design practices, but about the differences between individual and industrial design, about his creative process, and the experiences that inspire him.

Vilius Dringelis. Photo: Visvaldas Morkevičius

Aušra Trakšelytė: Would it be correct to say that you’ve returned to the object design? You’ve had a break of a few years, between the time you created the cradle and the table lamp to your latest works (the vessel With You, the coffee table Babylon, and the candlestick Vilnius Wastewater). What made you want to ‘come back’ (if it can be called ‘a comeback’)?

Vilius Dringelis: I wouldn’t want to make a separation between these periods, since I’ve been working intensely with different creative projects for years: in the fields of both art and design. For me, it is the same process, and it constantly keeps evolving and changing, depending on my experiences, the environment, my intuition, or skills acquired. In different periods, different practical, creative or personal experiences can influence my authentic professional choices. John Culkin once said: ‘We shape our tools and then our tools shape us.’ My latest works that you mentioned are the result of experiences, thoughts and notes from different design areas, or the outcomes of my previous works, and constant tours around exhibitions and galleries in search of my own creative method, aesthetic style and form. This quest probably lasts for as long as we exist; therefore, an artwork can sometimes take a month to make, and at other times, many years.

To tell the truth, I usually refrain from putting my creative work under a particular design term: I don’t like categorising. My work spans many different fields, I’m not trying to follow any trends or branches, or fit into any type of frame. It’s just not my goal. What interests me is the broader spaces, unexpected junctions, experimentation with ideas and processes, wandering around conventions, and seeking the limits of new opportunities. So when I work in different areas of design and try to combine them, I attempt to create an organism of its own, without having any design preconceptions in mind.

Vilius Dringelis, With You, 2021. Photo: Nerijus Kuzmickas

Vilius Dringelis, With You, 2021. Photo: Nerijus Kuzmickas

Vilius Dringelis, With You, 2021. Photo: Nerijus Kuzmickas

AT: Although you shun creative categories, you have nonetheless mentioned the ‘seekers’ and ‘finders’. If I understand correctly, ‘finders’ are researchers, those who collect information before they begin their creative process, while ‘seekers’ are those who start doing things without considering the context (without doing research), they trust the process and the possibilities for accidents and solutions that come along the way. Where do you position yourself?

VD: The context is somewhat different here. When I discussed this dichotomy, I was referring to David Galenson’s theory of creativity, focused on the typology of innovators. Some are described as perpetual experimenters or seekers, others as conceptual finders. I suppose the main difference between these archetypes is the fact that the former group don’t have a vision of what the final work should look like, and seek their solutions along the way; while the others prepare for the creative process in advance, meticulously planning their course of action, and having a clear goal, which makes it easy to tell when a project is finished. Both types search for something new, only in different ways.

I found this theory useful when interpreting different designers and their work, and understanding the environment they worked in, the methods they applied, and how certain contexts influence creativity. Take industrial design, it’s been formed by the consequences of industrialisation and modernism or global contemporary corporations, so the final piece is essentially formed by the reality of its production, the hierarchical chain. The creative processes are optimised, and decor is made redundant. Technical drawings and requirements are very important when making an item, the projects are made according to guidelines, and all further actions are usually linked directly to the initial problems and goals. That influences the concept and the stylistic choices. In essence, everything is done within a particular hierarchical frame, following an initial plan, and it seems that might overshadow the designer’s creativity; whereas creators of collectible design objects may question the traditional ideas of functionality, and improvise both with craftsmen’s techniques and high-end technology, without having a clear vision of the final result. Interestingly enough, it is an area full of contrasts, where the opposition between exact technical drawings (needed to carry out a plan) and manual labour becomes evident, since manual labour suggests immediacy and inadvertency, and can contradict the clear guidelines of mass production. Despite all this, I do not regard these types as either/or. As I mentioned earlier, I don’t want to categorise. It’s more of an observation or an interpretation of discipline, or perhaps a possible strategy for working in different environments.

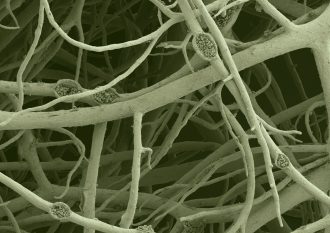

For instance, my creative method with foil has many layers, and is influenced by a number of processes. Initially, I observe my surroundings and think in 3D. I try to see into already-existing forms, and give them new functional meanings. I use foil to make imprints of them, and then reorganise those elements to convey new entities, objectivising commonly used objects in a new way. Later, I use an alternative principle to combine and join parts that kindle new possibilities for expression, since composing different parts by hand is dynamic and unpredictable. In this way, I interpret the qualities of bricolage, because the method I use for constructing different parts (and the meanings they carry) is unforeseeable.

Finally, when preparing the forms for either a single object or a series of objects, and working with innovative or digital technology, the way the object turns out may depend on the production technology or the materials used. Therefore, in design, I am more of a poet than an engineer, because I interpret the tools, technologies and production in my own way, and I make decisions during the process, studying the parts together and separately, searching for how to construct them in a materialised structure; hence, I simply cannot grasp what the end result will be. Although I construct the puzzle by myself, I seek to get lost in my fantasy world: I am interested in methods of manipulating and transforming materials. Yet functionality is important to me as well, and in some cases I can work in the industrial field too.

Vilius Dringelis, Vilnius Wastewater, 2022

Vilius Dringelis, Vilnius Wastewater, 2022

AT: You mentioned your creative method with foil, which inspired your bronze vessel With You. Not only did it capture the essence of your creative process, but it also embodied a certain period in the pandemic, when we formed the habit of ordering takeaway food. Yet it seems that the foil became like a ‘light bulb’ over your head that you would later bring with you to the city. This way, you ‘took’ many surface shapes, elements, or details from around Vilnius, and in 2022 created the candlestick Vilnius Wastewater. This work speaks to me, because it steps over the limits of its material form. In other words, ‘glued together’ in a dynamic way, the elements become the final result. And yet the important thing is that different spaces, times and experiences lie in it. Each of us is encouraged to create our own cityscapes, trajectories, or archaeology of sense-making. Were the reorganised elements and details accidental? Or did you seek to make a psycho-geographical portrait of the city? What portrait would that be?

VD: I was inspired by the signs and processes that are defined through different principles in various contexts, which can create alternate meanings. For example, the Cargo Cult religion in Melanesia sprang up during the Second World War when tribesmen encountered Westerners and their cargoes. They began believing in the magic powers of Western goods, performing rituals with models of airports or planes made from coconuts, straws and rocks, to attract cargoes full of goods. Or consider the scientific inventions that were only successful thanks to unintended errors. For instance, Richard James had been trying to create a gauge to measure the power of ships. However, as he was working with tension springs, one of them fell to the ground, giving birth to the product now known as a Slinky. Or take Pfizer’s UK92-480 pill, which treated angina by constricting the arteries, which became the pill Viagra, and so on. All such cases share a common core: the objects, concepts or parts of them were not used for their initial purpose, but by going off-script instead. So when I discovered the foil method, I wanted to explore this tool further. I began to use it as a sampling tool, creating a sample library, just like a musician collecting and interpreting various surrounding sounds, creating some extraordinary phenomena in their musical compositions. Wandering around the city in search of various details turned out to be very beneficial for the exploitation of this tool, both physically and mentally too.

The case of the candelabra Vilnius Wastewater was irrational self-exploration guided by my inner voice or intuition. I was walking around town creating hypotheses. The uniqueness or individuality of this act is determined by personal qualities or by the subconscious. I am currently working with objects that will probably highlight certain stories from different perspectives. When I wander around different cities and encounter various forms, the functionality they might add to the thing I am working on is not my only priority; this wandering is also a rather subjective relationship between the artist and the environment, allowing me to capture correspondingly subjective narratives, signs and periods in an object. And yet the pluralist object allows the viewer to interpret the scenario in their preferred way, based on their personal experience. I really like this kind of intimate relationship with the viewer, so I opt to work in two directions, with and without references.

Vilius Dringelis, Red Rose, 2021. Photo: Jonas Balsevičius

Vilius Dringelis, Red Rose, 2021. Photo: Jonas Balsevičius

AT: So in design, you are more of a poet than an engineer, and in your creative practice you seek to overstep the limits of the discipline itself. In general, I’d like to agree with you, and say that design today is a very complex thing: it’s become less of a profession and more of an outlook, closely related to the personal qualities of each creator. What personal qualities (in your character) get transferred into the stylistic or thematic features of your creative work?

VD: Although I am quite a melancholic and reserved person, I am also full of contrasts. I can’t conform with the state of comfort. I can retreat and observe complete silence for a few weeks, but at times I need intensity and flux, in which I find inspiration to then retreat into my creative pondering again. It might sound odd or funny, but I used to like hanging around in supermarkets, just to observe the hustle and bustle, people, and their actions. As an onlooker, you can observe many curious situations, and manipulate different scenarios in your head, trying to guess what people are thinking or how the environment influences them. Plus, aimless wandering around a city was a way for me to escape depression and the feeling of loneliness, like meditation. I’d try to stumble over new spaces, buildings, corridors or rooms, to get the sense of being lost and discovering something. I’d end up in odd situations or community gatherings, which I wouldn’t otherwise ever have visited. For the same reasons, at one point I began spontaneously travelling and wandering around big European cities. It would liberate me, and give me new experiences. I’d follow my intuition, so that each moment could bring something unexpected. All of this prompted my creative method with foil: later, during the pandemic, I returned to studying for a design MA at Vilnius Academy of Art, and, quite naturally, this wandering became part of my creative research and work. So I began enacting this practice in objects.

I like subtle but simultaneously contrasting phenomena and discrepancies in all contexts. I don’t see eye to eye with those who advocate one truth only, I am all for constant discussion, and I think it is the only path to liveliness and vivacity.

Vilius Dringelis, Babylon, 2022

Vilius Dringelis, Babylon, 2022

AT: What features do you value most in design? What role does it play in your everyday life?

VD: I once heard a saying that really stayed with me: ‘If we looked at a general picture from a macro perspective, we’d see sameness; however, if we looked from a micro perspective, we’d notice individuality, all the discrepancies and errors.’ So if we compared ten mass-produced chairs from the same series from a distance, we’d say they’re all the same, uniform. However, if we looked close up, we would probably be able to see some differences in the screws, or how some parts are joined together, how the textures differ, the imperfect smoothness of the paint, and all the minute defects. This made me consider how the extent of errors suggests questioning the limits of tolerance. I realised that I was fascinated by the discrepancies in production, because it grants the object energy and authenticity; therefore, as I mentioned earlier, in design I really value the unexpectedness of the creative process, which can turn into wonderful discoveries.

Moreover, to me, design is about building a relationship and communicating in every sense of the word. We create objects and phenomena that influence our thinking and behaviour. Whether we aim at projecting a functionally innovative object, solving an ergonomic problem and making people’s lives easier, or depend on collectible design that tells stories and describes concepts, or graphic design; in all of these cases, I believe, I value creativity most, as it can open up and keep expanding our perception for ever.

Vilius Dringelis, Goštauto 5a, 2022

AT: Finally, if you don’t mind, I’d like to ask you something I’ve already asked the designer Vytautas Gečas (who introduced us to each other). What do you think is important and must be done in Lithuania so that design becomes even better known and grows here? After all, there are so many interesting artists whose works are presented at various international design exhibitions and fairs, and they win recognition and important awards (you being one of them). More and more personal and group design exhibitions are held in both commercial galleries and state institutions; universities and other institutions of higher education continue to offer courses in design; young designers either study or practise at institutions abroad …

VD: I believe everything is evolving organically and in the right direction. We have a great open community, in which people support each other. Many different artists have their unique point of view and creative practices. And many organisations help them. The local design schools prepare strong graduates. There’s also the possibility to travel abroad, get some experience, and share it after coming back. Lithuanians have always been very eager and able to cultivate their intuition: it is clear that we are moving forward in all areas.

I have grown up partly in this system too, and I am extremely happy to have been able to study in the Design Department of Vilnius Academy of Art. And now I have the opportunity to collaborate with the Lithuanian Design Forum in presenting our products abroad, with the Lewben Art Foundation in creating design solutions, and with the Vartai Gallery, which now presents my work. You can see my latest work in its showroom.

Even more active cooperation and participation in the international arena, both individually and for organisations, would be desirable. If it were up to me, the network would be global. It is very important not only to share one’s culture, but also not to be afraid, and accept other cultures, that is, to organise exhibitions of work by foreign artists that involve our local communities too. We need to invite different designers from abroad to give public lectures and share their experience: this kind of cultural exchange could help us evolve, and present relevant and interesting content not only to local residents but also to nearby regions. All of this would accelerate our growth.

AT: Thank you for the conversation, Vilius.

Vilius Dringelis, White Vase, 2022. Photo. Nerijus Kuzmickas

Vilius Dringelis, White Vase, 2022. Photo. Nerijus Kuzmickas

Vilius Dringelis, Open, 2022

Vilius Dringelis, Open, 2022

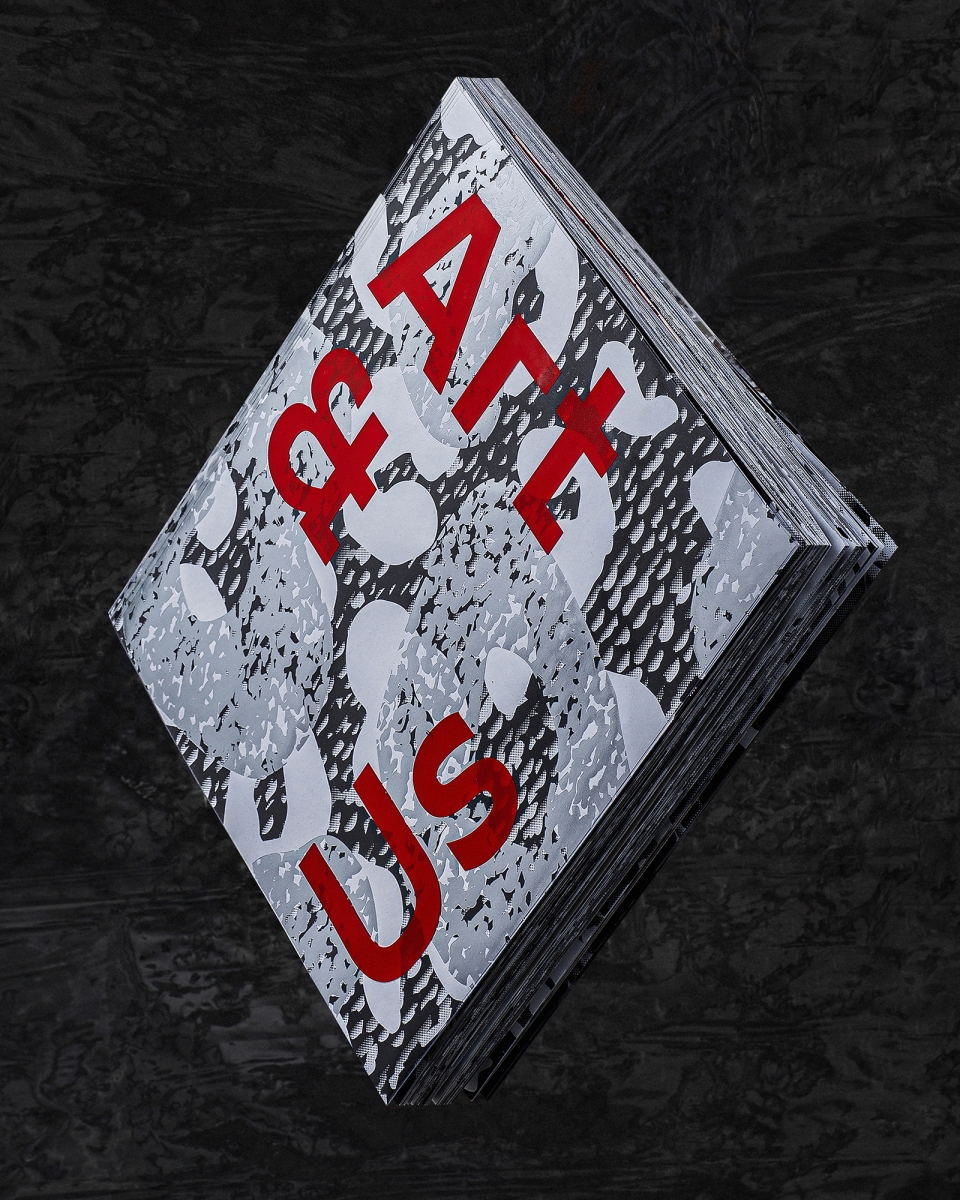

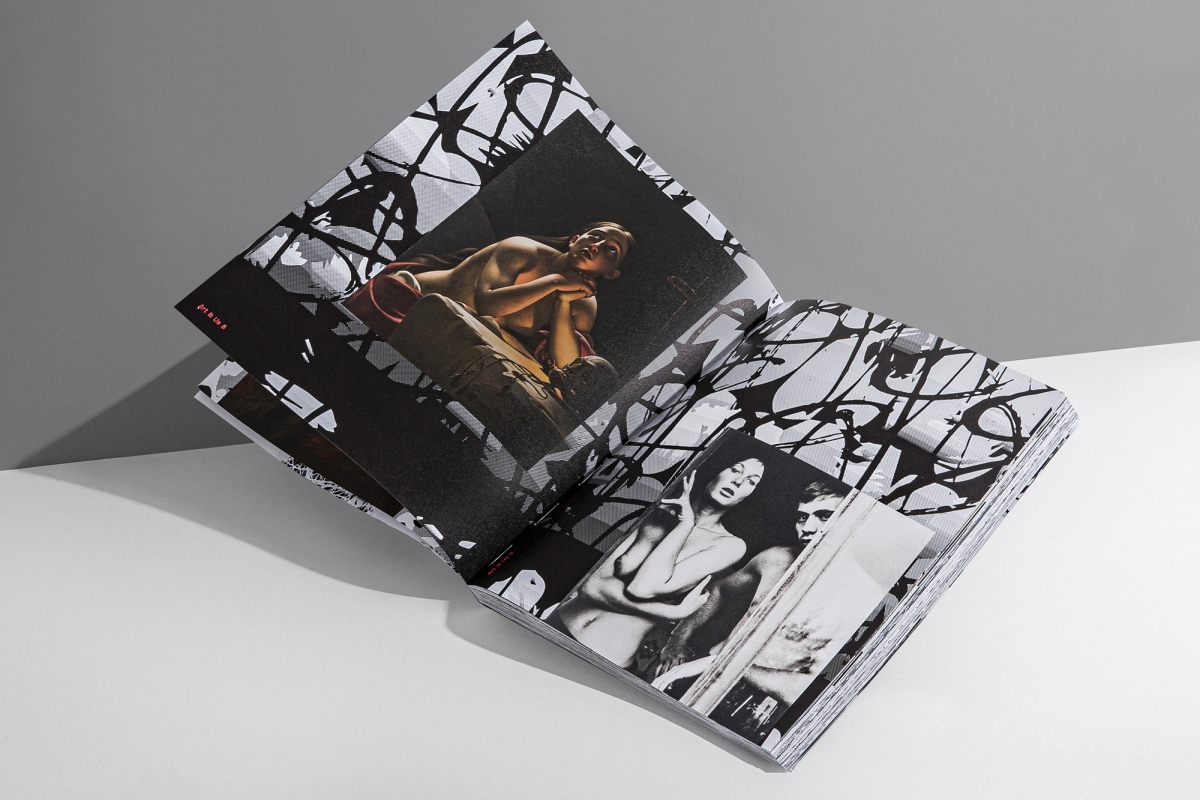

Vilius Dringelis, Lewben Art Foundation Art & Us, 2019. Photo: Martyna Paukštė

Vilius Dringelis, Lewben Art Foundation Art & Us, 2019. Photo: Martyna Paukštė

Vilius Dringelis, Vilnius Wastewater, 2022

Vilius Dringelis, Vilnius Wastewater, 2022

Vilius Dringelis, Vilnius Wastewater, 2022

Vilius Dringelis, Vilnius Wastewater, 2022