In July, the building of the Estonian Academy of Arts is on holiday. I would like to believe the rooftop is enjoying sunbathing, with a view of the water. The other side’s terrace prefers to take pleasure in the sight of a medieval, picturesque town, overgrown with greenery. The furnace in the glass department cools off, and the keys of the grand piano are tucked in. This time of year, even the lifts are allowed to take a nap.

Only the belly of the building defies this pace. These weeks, EKA gallery—the main exhibition space of the Estonian Academy of Arts—is hosting Print Muscle, the youth exhibition of Tallinn’s Print Triennial. Whereas its last edition took place at the Contemporary Art Museum of Estonia (EKKM) during their winter break (ironically, that year, the triennial carried the Estonian name ‘Soe’, meaning warm), this one organically brings young makers to the place it often all starts—the academy.

Tallinn Print Triennial ‘Print Muscle’, EKA Gallery, 2025. Photo: Odie Lap Chun Chow

Tallinn Print Triennial ‘Print Muscle’, EKA Gallery, 2025. Photo: Odie Lap Chun Chow

Could one look at an academy as a gym? A place to actively warm up. Aside from anecdotal conversations I used to have with colleagues, where we compared the art field with a football club, (can we turn FC into AC?), I have personally witnessed this gallery occupied by a group of yoga practitioners, balancing the most flexible positions. Dutch writer Maartje Wortel acknowledges the inevitable bond between art and gymnastics. In her article in De Witte Raaf, the focus lies on the form. The human body (its tones, outlines) is one of the focal points of the earliest canonical forms of art, such as painting and sculpture. In this exhibition on printmaking, however, another aspect of muscles comes into play. Aside from their aesthetic rewards, we all know how muscles are actually process-based. Aside from keeping our body afloat, giving posture and substance to our bones, they rely on training and maintenance. They are an object of potential. The reach of this tissue, or mousse (blame etymology for the ick factor of this one), depends on practice and repetition. It was in the academy that I realised how a maker does not work with exhaustion in the sense of emptying (as if there was a jar of finite ideas), but through training. Artistic endeavours function like a muscle that requires training in all it encompasses: rehearsals, rest, frustration, waves of energy…

Training means hard work. Mindaugas Aniūnas’ work hangs on a clean wall, as well as in the last rough corner, which reveals the gallery’s original brick. The artist uses the hexagonal shape as a commonality to guide him in comparing human infrastructure and bee habitats. Six prints and an aluminium plaque reveal images of infrastructure carrying powerlines, some more clearly recognisable than others. The ink and pressure of the plaque have tempered their well-calculated shape. Pieces of beeswax are placed in a seemingly casual manner on the gallery’s floor, accompanied by two other prints that contain a cover. Long nails allow for a phantom image to float in front of them.

This body of work is a lot, maybe even a bit too much? It reveals every part of the process, which might only leave a little to be filled in. Yet I am triggered enough to start looking for what is not there. The prints covering another image bring my focus to what attempts to be hidden. I am reminded that both systems generate a buzzing sound. Could one see bodies through these depictions of infrastructure? Both its inhabitants are labourers. The size of worker bees’ wax glands appears to depend on the age of the worker and the number of daily flights (as they gradually atrophy). In similar ways, building material is often adapted to the human body (think about bricks, produced to fit exactly in a human hand). One could say the body leaves a mark in these processes.

Tallinn Print Triennial ‘Print Muscle’, EKA Gallery, 2025. Photo: Odie Lap Chun Chow

Marks and traces are exactly what guide this exhibition. A metal wire carries a selection of prints. I am distracted by the shadow work of the wire on the wall in relation to Aniūnas’ work. Thus, I approach the work from the textual side. Each paper contains a sentence noted down by typewriter: ‘I am as transparent with Agne as three minutes in the acid of an aquatint’. It appears to be documentation, with the character of a timesheet. This makes it a conceptual gesture. The piece relies on an invented rule or formula, which contains a constant (‘I am as transparent with… as …minutes in the acid of an aquatint) and variables (name and number of minutes). The rule is applied repetitively, and what we see in the gallery is its outcome, uncompromised. Aside from the sense of control Gintautė Siniakovaitė gains through such a method, the trace in Transparency lies in the impact on the other. What trace do we leave after an encounter, and what marks do other makers make on another’s practice? How much space do others take up? The use of a formula is softened by the medium of aquatint. Comparable to etching, aquatint is distinguished by its use of tone rather than line.

I cannot help but feel something surprisingly warm in such a rule-based work. I imagine workers’ aprons touching while greeting each other, or a few sets of hands sharing the sink to wash off remnants of ink. It also evokes the idea of constellations between people as tones, where borders are a mixture of colours and flavours. Traces are furthermore a sign of collectivity—contamination, in the best sense of the word.

The sgraffiti of Loora Kaubi stand tall in the gallery, yet they were once commissioned for Elle Viies’ performance Pastoraat. Those marks go both ways. I remember the performance to be fairly coloured by Kaubi’s practice surrounding the movement. The work appears dark and gloomy but reveals glimpses of light matter, such as plaster and metal wiring, which are part of the structure of the ‘canvas’. Sgraffito is a process of meticulous scraping, often used on ceramic or plaster. Kaubi not only depicts but also generously reveals what lies at the core of things. The visitor is confronted with abstract patches, as well as a hand (of the maker?), carrying a carving tool. Is that not a good metaphor for friendship and collaboration? Shedding layers of protection, all for the noble cause of better understanding the soil we are working with.

Gently hidden underneath the wood of the second floor, Daria Titova follows a similar approach of laying bare—this time, the impact or the traces are those of a city being invaded. Rather than scratching the surfaces, she digs deep (under the ground), stays sharp on the current level and reaches above through a textile triptych of embroidered depictions. In Titova’s work, it is not ink but thread that leaves a mark. It also tastes a little like an illustration or even a design practice.

Tallinn Print Triennial ‘Print Muscle’, EKA Gallery, 2025. Photo: Odie Lap Chun Chow

Tallinn Print Triennial ‘Print Muscle’, EKA Gallery, 2025. Photo: Odie Lap Chun Chow

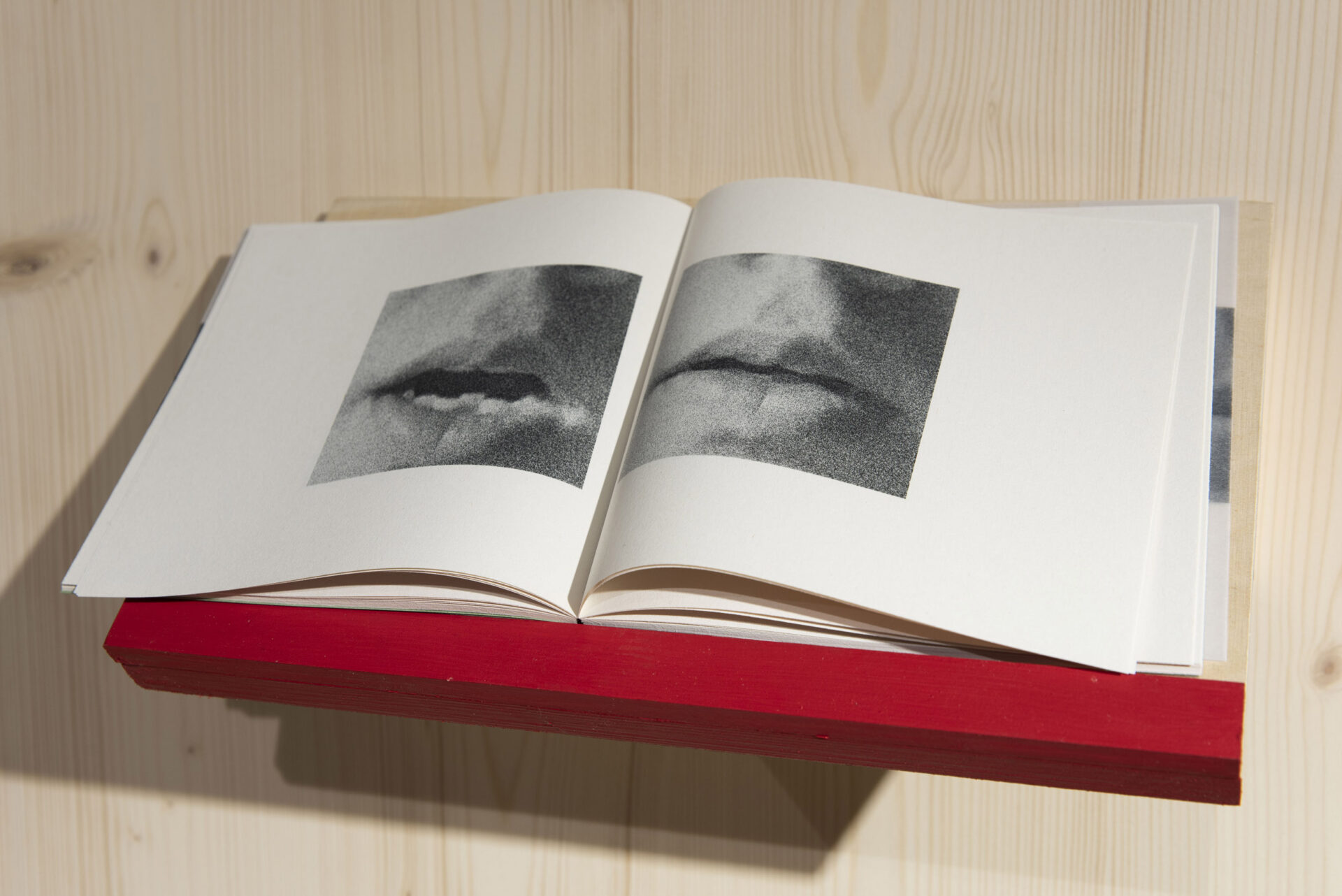

The second floor of the exhibition is an indispensable elaboration on that. Agnes Isabelle Veevo brings together self-published material of young graphic designers. The challenges these publications carry in a gallery setting are not unimaginable for graphic art. How can one fully experience their tactile nature, in the choice of paper, the blending of ink in different light conditions and the particular character of the mounting or binding?

Else Lagerspetz once wrote in an essay, ‘the nature of self-publishing lies in the hassle it entails—and the freedom that this hassle grants.’. If writing, designing, project managing and publishing simultaneously is not training, then I do not know what is. This intense process of multitasking lays bare a lack of infrastructure or a gap in platforms for certain narratives. This, too, is similar to (graphic or not-so-graphic) artist-run initiatives. Whether a publication revisits vernacular shop signs in Tallinn (Merendi), looks through archives of political image making in Morocco (el Khammas) or coins ornaments on toilet paper (Cremers), aside from self-publishing (indirect) institutional critique, there is the important element of freedom Lagerspetz mentions. These published works have a sort of uncompromised quality to them. They bring something to you as if you are hearing it first-hand. Since a genuine message often lies between its intention and what is literally said in words, in this active, unyielding medium, something is bound to be felt.

The red colour in this reading room, beneath each plinth showcasing a book, sitting in the beanbags… it all reminds me to take a moment of pause. If I am not mistaken, it is the go-to colour for a ribbon as a bookmark. While returning from the south of Estonia after a long weekend away from the city, a red light also means to take a break from pushing the clutch of my old car. Muscles do benefit from more than just being trained through exercise: they ask to be stretched. This is a natural activity which not only mammals and birds do. Even spiders apparently need a stretch. Stretching intuitively happens after experiencing confined spaces (are commercial publishing platforms not a medium that is too tightly defined?). The goal is to gain more flexibility and capacity. Where better to do so than at an academy?