In her solo exhibition ‘Tidal Tear Sediment’ at the RIXC Gallery in Riga, Sabīne Šnē explores the fluid interrelations between water, humans, more-than-human, and shifting environments. The philosopher and publicist Sofija Anna Kozlova spoke with the artist about how water shapes and unites all forms of life, and its significance in ecological, social and political contexts.

Sofija Anna Kozlova: Speaking of water, the topic of your exhibition and the topic of our conversation today, what does it mean to you?

Sabīne Šnē: It means being alive. It’s about this element or entity, or, as some call it, this organism that sustains us, and because of which we are here. We can ascribe this characteristic to many more-than-human entities, but water is necessary for all forms of life on Earth. For me, it is also a force and a motion, something that is always in a constant state of becoming.

SAK: Do you think that the local context plays a role in how you connect with water? In the video that is the centrepiece of your exhibition ‘Tidal Tear Sediment’, you mention the Baltic Sea. And I wonder whether water is an abstract entity for you, or is it more situated and localised?

SŠ: I first developed an artistic interest in water when I was far from different bodies of water, in the middle of a big city, and far away from the Baltic Sea. I began to miss the horizon and walks along the beach. That was the first impulse. Then I stumbled on an article by Rachel Carson entitled ‘Undersea’. It was published in 1937, but it still feels incredibly relevant. It attempts to approach water from the perspective of the different creatures that live in it. I was absolutely fascinated by it. I’ve always been interested in more-than-human intelligence and perspectives on the world. After reading more and more about water, I eventually discovered Astrida Neimanis and her ideas on hydro-feminism. I was hooked.

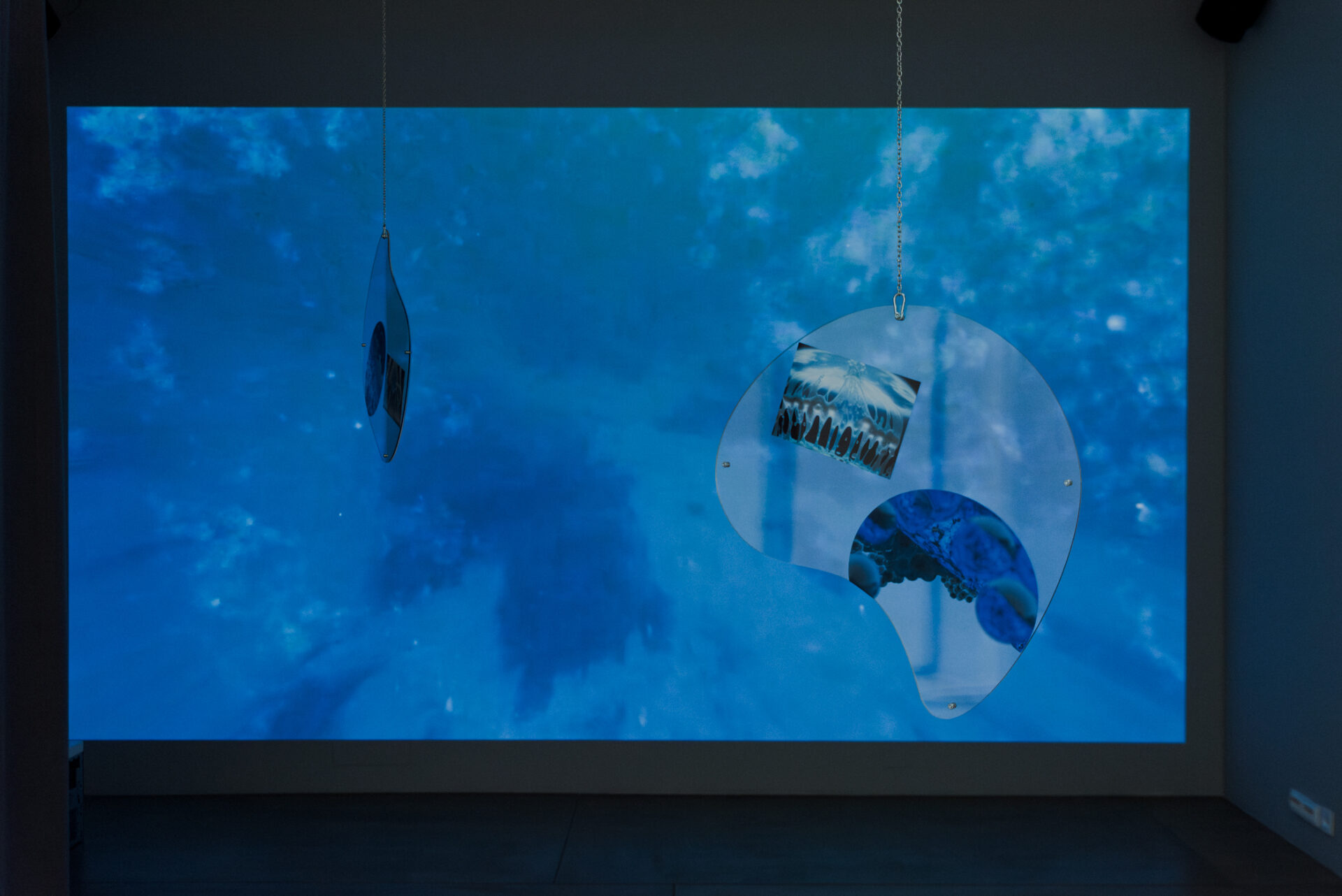

Sabīne Šnē, ‘Tidal Tear Sediment’, 2025. Exhibition view at RIXC Gallery, Riga. Photo: Lelde Gūtmane

SAK: Have you found exactly what the hook in hydro-feminism was? I mean, from one point of view, it’s super-scientific. Translating the theoretical foundations of hydrofeminism has made me appreciate the technical details of the work. For me, coming from a background in philosophy, all the geography, biology and chemistry vocab just wasn’t there. At the same time, somehow, this theory resonates with people, despite its complexity. Where do you think its appeal lies?

SŠ: I think it’s in the very simple thought that all of us are linked with one another through water. It might sometimes be hard to comprehend that the water someone is drinking in China right now could be in my water glass a while later, due to the planetary water cycle. Water travels constantly through the Earth, the atmosphere, and our bodies. It has been imprinted in my brain since primary school that about sixty per cent of the human body is water. So water is always close to us. We drink water, we wash ourselves with it, we clean things with it, and we are connected to each other through the flow of water. I think that’s the power of hydrofeminist ideas. As you said, there’s much more in Neimanis’ works. But I don’t think we should be scared of biology and chemistry terms and facts. It is part of hydrofeminism’s success, as it grounds the theory in scientific findings and methods, making it something very real.

SAK: I think you’re right. Water is supposed to be both a figuration, an imaginary through which we can interpret the world and the relations that constitute it, but also something very tangible that is literally just us. You mentioned the fact that sixty per cent of our body is water. It’s a basic fact that we can literally feel within ourselves. Similarly with water-related illnesses and pollution: we can feel them, but we need someone to point to the origins of these problems. And this is something hydrofeminism does very well. It shows how water is the key to understanding many different financial, social, health-related and environmental issues. But the heart of hydrofeminism is the move from the local to the planetary. It’s a huge step, isn’t it? To move away from what is around you, and where you can directly feel the effects, to the unknown waters of China or wherever.

SŠ: I think I approached it step by step while preparing for the ‘Tidal Tear Sediment’. I wanted to explain the hydrofeminist ideas through my own practice. First, I read a lot about the planetary water cycle, or the hydrological cycle. I first heard about it at school, or maybe even in kindergarten: a water molecule falls from the cloud, reaches a river, evaporates, condenses, and does some other things. Then the journey takes it into the human body, where it travels through us, evaporates again, and goes back into the atmosphere. Looking at the planetary water cycle helped me simplify the core idea of shared planetary waters. Its constant movement unites everything in this world and connects to every single body of water individually.

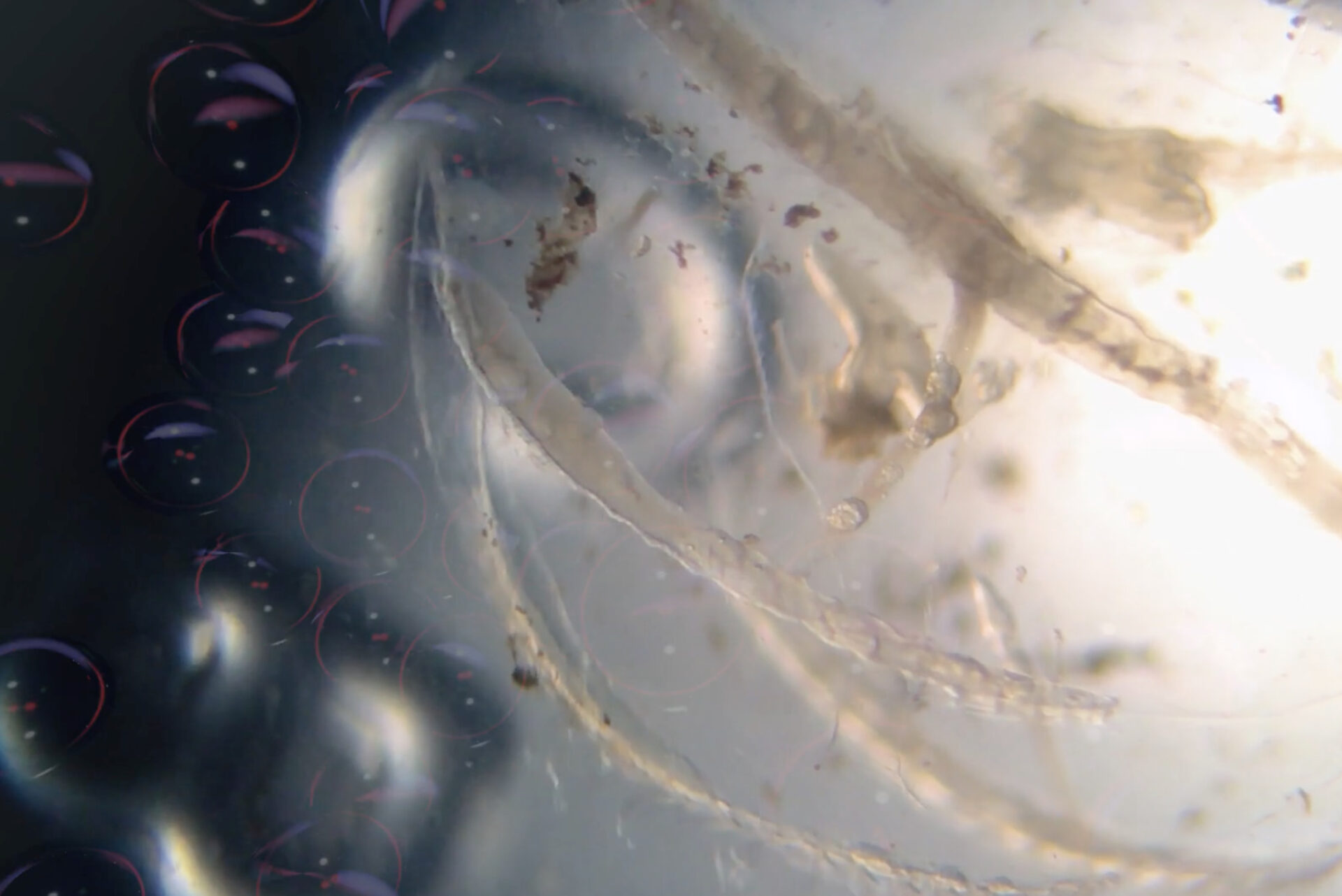

Then, I started thinking more about connecting the water in my body with other bodies of water. That’s when the Baltic Sea came into the picture. I wanted to incorporate something from my favourite beach in Latvia, so I collected water samples and brought them to London, to a friend who works in a lab. I looked at the water through a microscope, observing all the small entities that live in it. Honestly, it was slightly disturbing. That’s when I realised that this massive planetary water cycle is made up of small, microscopic organisms. Then I read about water in our bodies, in the bones, the brain, and all the magical things that are constantly happening in our bodies. I guess I had never been fully aware of it. After that, the task was just to put these different discoveries together and create the work.

We always tend to think from our individual perspective, which means we start by thinking about our surroundings. That’s also why water is so fascinating. If we understood how much our bodies are connected to, say, the most polluted river on Earth, I think we would try to live more sustainably. We would think more about the Earth and its ecosystems, because we would understand ourselves as part of it.

Sabīne Šnē, ‘Tidal Tear Sediment’, 2025. Exhibition view at RIXC Gallery, Riga. Photo: Lelde Gūtmane

SAK: One thing you mentioned is simplifying the idea of hydro-commons, which sometimes makes me wary. I understand that we know the hydrological cycle from childhood, but, as you said, there is so much more in that water, like the molecular relations and the chemical constitution. So simplifying the complexity of the worldly constellations might threaten theories like hydrofeminism that are so simplistic on the surface. Did you see it as a challenge when expressing the ideas through visual media?

SŠ: Not really. At some point I realised that hydrofeminism is a lifestyle. Maybe that sounds a bit pretentious. It’s not just an idea, it’s a way of living with the understanding that you are part of something bigger. You’re just part of the chain of life. Simplifying it might do the theory a disservice, but if you view it as something that shapes you and your approach to the world, you shouldn’t be afraid to make it personal.

Sabīne Šnē, ‘Tidal Tear Sediment’, 2025. Exhibition view at RIXC Gallery, Riga. Photo: Lelde Gūtmane

SAK: It makes me think of another aspect of water that is addressed in hydrofeminism: the unknowability of it. Hydrofeminism invites us to understand the limitations of our own understanding and be okay with that. The deep sea is the best example, it’s the terra incognita of our contemporary scientific world-view. I’m super fascinated by deep-sea creatures; reading hydrofeminism has probably planted this interest in me. I’m ready to be surprised by the deep sea. Maybe there is a limit to how far our explanations can go. In the end, it’s you and your own experience. I noticed that in the centrepiece video you sort of give a voice to a water molecule. How did you come to this way of telling the story?

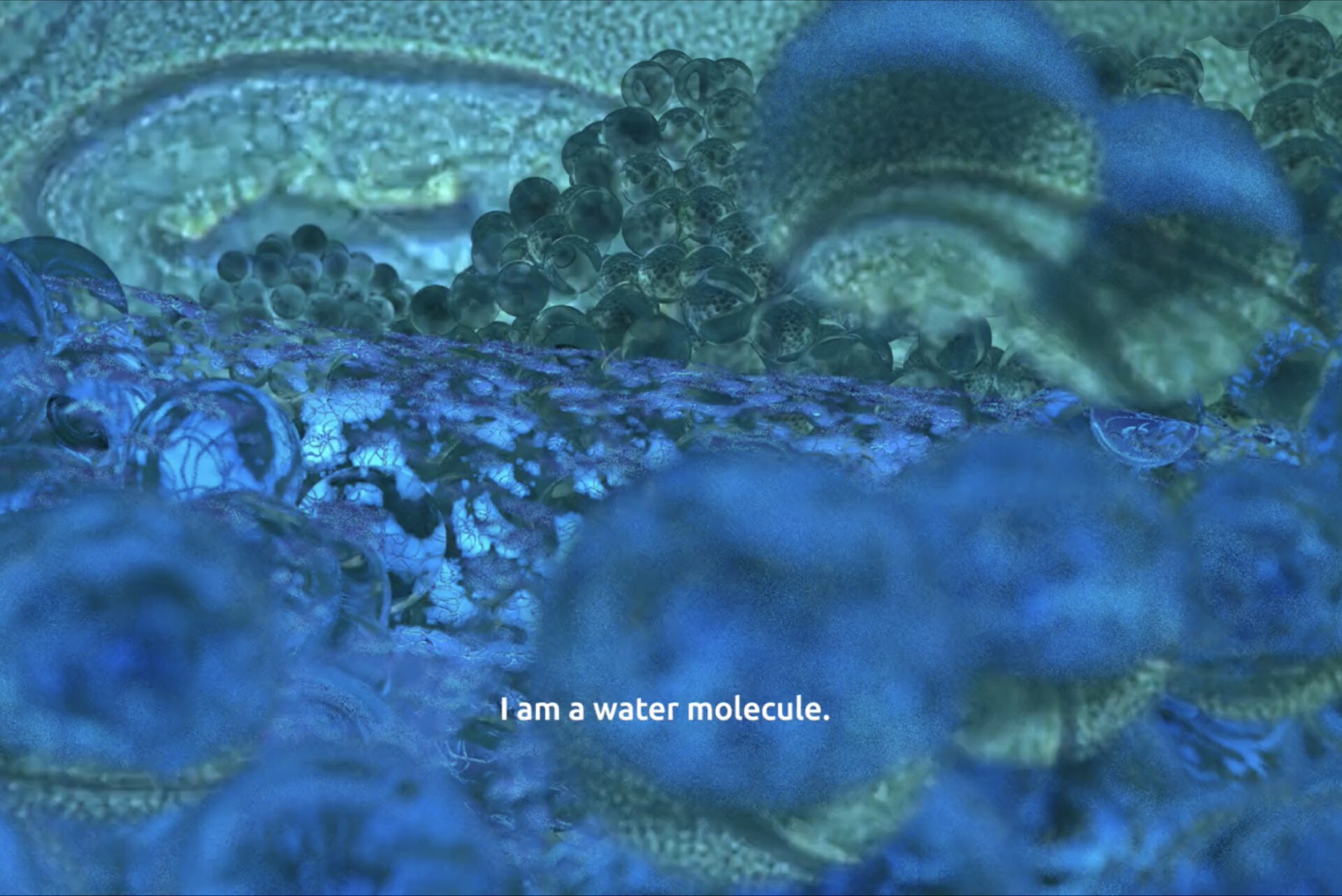

SŠ: I really wanted to create the work from the perspective of something in the water. My first thought was a fish or a seal. But then, under the influence of hydrofeminism, I started to look into the world of water molecules, their amazing qualities, and how they bond with each other. Through these bonds, they determine the structure of water, and, indirectly, other biological entities. That was the final impulse to make the main narrative of the video piece from the perspective of a water molecule. This also allowed for more speculation. I didn’t have to focus so much on how it is in real life, like in the actual Baltic Sea. It could be more abstract, but still connected to the place, to the body.

Sabīne Šnē, ‘There Are Tides in the Bodies’, video still, 2025. Part of the mixed-media installation ‘Tidal Tear Sediment’

Sabīne Šnē, ‘Tidal Tear Sediment’, 2025. Exhibition view at RIXC Gallery, Riga. Photo: Lelde Gūtmane

SAK: Building a first-person narrative might impact how we perceive ourselves. Were there moments in this process when you associated yourself with the molecule?

SŠ: Yes, it meant moving toward the ghostly realm I’m not so comfortable with. There were moments when I was in my studio late at night, thinking about water, when I suddenly vividly realised that watery movements were happening inside me. It was unpleasant.

SAK: Thinking in this way about identity is difficult. First, to a certain extent, there is nothing that remains static. Water comes and goes; it flows and becomes different; it becomes other bodies of water. We cannot rely on it. Second, there is nothing else in you. You’re just an assemblage of different bodies of water, like molecules. Has this had an impact on how you see yourself?

SŠ: Absolutely. But this started before the exhibition, a couple of years ago, when I was working on my first solo exhibition ‘Partner, Parasite’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. It was a reflection on human parasitism, and how we could create a partnership with the ecosystems that sustain us. That’s when I discovered the Gaia Hypothesis by James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis. Margulis, especially, talks a lot about bacteria, different micro-organisms, the origins of life, and how these tiny organisms came together in water, and decided that, instead of eating each other, they would become partners. She was a microbiologist, so it’s her area of expertise. That must have been the moment when I realised how many bacteria there are in my own body. After that, with each artwork, I became more and more interested in these alliances. Hence, this belief grew stronger: that we are truly part of nature, and we need other organisms to survive. There is no other way. We can’t exist without them, even if they can exist without us.

Eventually, this led me to think about how we treat our bodies, and whether we are kind to them. Everyone should appreciate that they are a marvellous world of other worlds, intimately connected with other bodies. So we are individuals with our own place in a wider ecosystem.

Sabīne Šnē, part of the mixed-media installation ‘Partner, Parasite’, 2022. Solo exhibition view at Kim? Contemporary Art Center, Riga. Photo: Ansis Starks

SAK: Another interesting notion that plays a role in hydrofeminism is the notion of membrane. The idea is that even though everything that we are flows in and out of us, still, for this impossibly brief moment of time, it is one, contained within the porous borders of the body. We shouldn’t be indifferent towards the differences of our situatedness. First of all, we speak from our human perspective. Whatever post-human theory you choose, the question always is, are we really capable of abandoning the human? This relates to your water molecule. Don’t you see the danger in making the molecule human and returning to the human-centered perspective again?

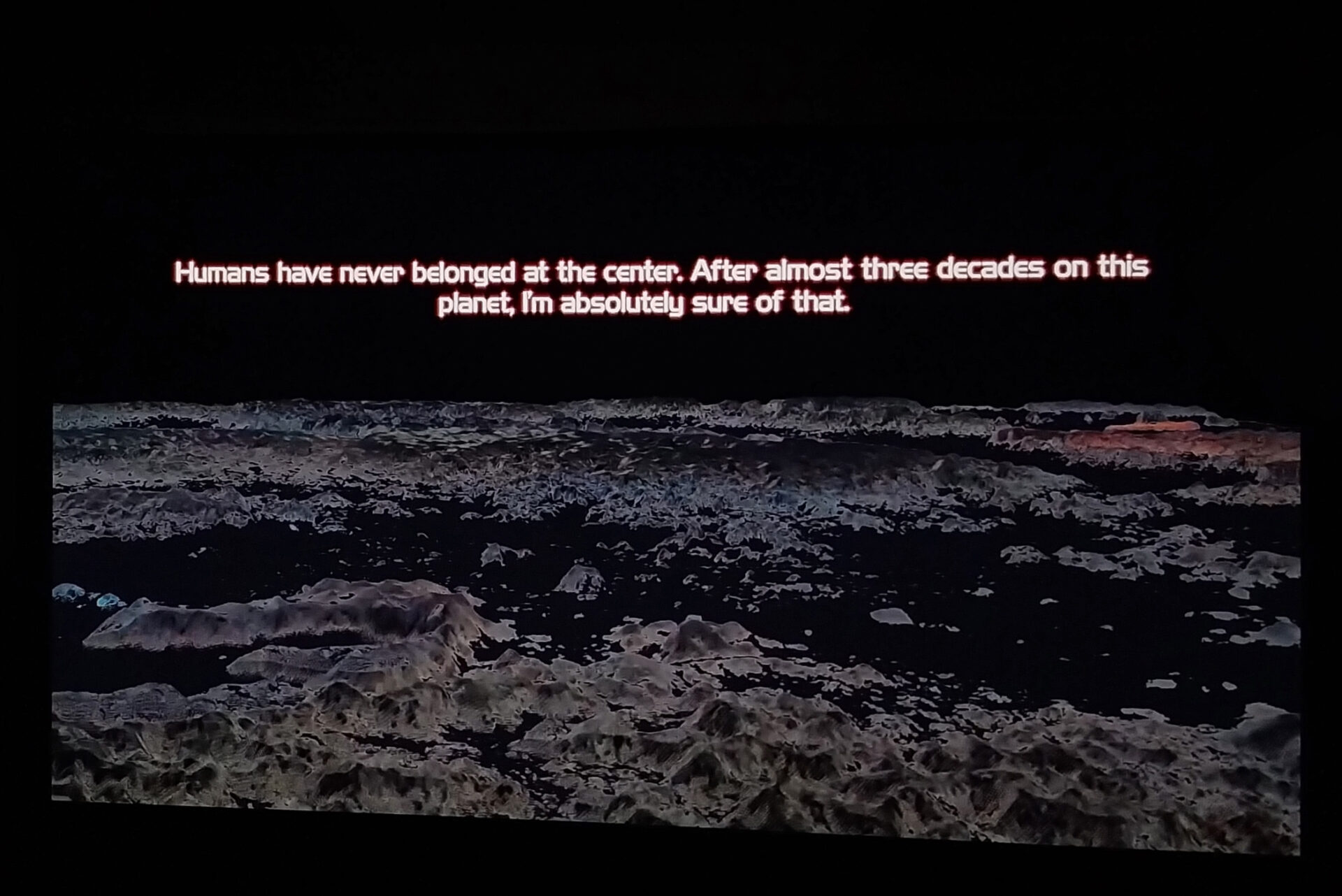

SŠ: It’s very tricky. I’m fully aware of that. Especially because I use language as a means of expression in my artworks. While there are different types of communication in the world and across different organisms, language is specifically human. So I immediately position these different entities in our human world, out of their natural habitat, which is probably not fair to them. That being said, if we use language responsibly, trying to make sense to ourselves and to others, it can be one of the best tools we have. I don’t think language is problematic per se; rather, it’s the meaning we assign to it. For example, more-than-human or non-human: terminologically, I find them deeply problematic. Maybe not so much in English, but in Latvian these terms carry a negative connotation, as if they were somehow less than us humans. If all of us, ‘us’ meaning humans, acknowledged that, like every other organism on this Earth, we are products of an event that happened 3.8 billion years ago, we would appreciate other organisms more. We should stop seeing ourselves as the pinnacle of evolution, and instead immerse ourselves in the environment around us. We are not smarter than ants or better than bees; each of us has specific qualities. We should celebrate our differences, look for commonalities, and learn from other entities as much as possible.

SAK: The notion of the body of water does exactly that. The ‘body’ of the body of water, in Latvian, we commonly use the literal translation, but actually it refers to containers of water, like ponds, cisterns, bottles and seas. For me, that makes a difference. If we think about the human and the non-human, then a negative aspect of otherness is associated with beyond-human bodies. But if we approach the question from the other side, taking the other as the starting-point and understanding ourselves by reference to not-even-living entities like ponds, as assemblages of water, it’s not them that are made like us; rather, it is we that are made similar to them in certain respects like our material constitution.

SŠ: Absolutely. There is this human-centered perspective. Many issues come together with it. The sooner we move away from it, the better off we will all be.

Sabīne Šnē, video ‘Caves of Our Insides’, 2024. Screening at the event ‘Granny Ludski’s Wild Gardening’ at RIO Cinema, London

Sabīne Šnē, part of mixed-media installation ‘Terrain We Traverse’, 2024. Exhibition view at Kupfer Gallery, London. Photo: Rita Silva

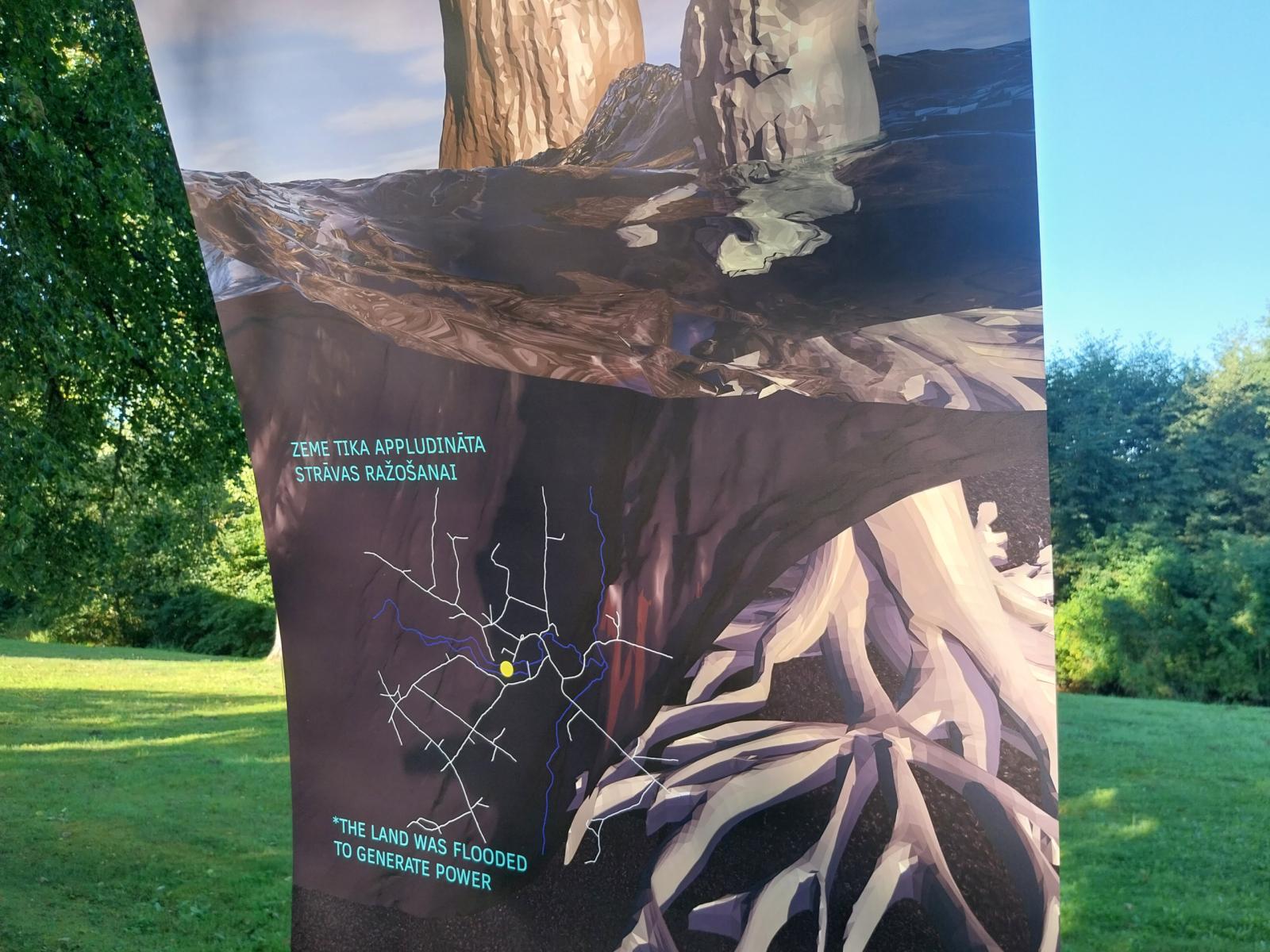

Sabīne Šnē, part of the artwork ‘Stolen Verdure. Soviet Legacy’, 2024. Exhibited in a public outdoor space next to the municipality building in Padure, Latvia

SAK: You mentioned in a previous exchange that you hate the word Anthropocene. Neimanis has a long critique of the word as not radical enough because it takes the human, Anthropos, as the starting point. Even if now, within the discourse of the Anthropocene, the human is not seen as the Crown of Creation any more, the discourse is still centered on human activities. There is a lot of truth in it, but I think we should realise that humans have a different level of responsibility. In that sense, maybe it makes sense to speak from our own point of view, and not to deny the specificity of the human condition. Even if I’m a body of water, there is still something very particularly human in how I can influence the world, which determines the responsibility I have to bear.

SŠ: I agree. Going back to the Anthropocene, one of the reasons why, as I told you, I hate the word is because it unjustly places all of us on the same level. You and I will never cause as much damage as a giant oil company. And because of that, we are not as responsible as they are. Similarly, although I really don’t like the term Global South, because of its strong ties to colonialism and exploitation, it’s important to recognise that the people living there, who are already facing water shortages, don’t bear most responsibility, even though they suffer the most.

SAK: What do you make of it? I sometimes fear, especially in the context of theories, it’s common to just criticise. But that doesn’t change the way we act. Do you think there is a positive take on these issues? There is another keyword, care, which represents the structure in which I believe we should address these issues: not by judging one another, although there are clearly dissimilarities and inequalities that should be paid attention to, but by focusing on how each of us could benefit water from our own position.

SŠ: Absolutely. Judging isn’t helpful to anyone. It’s important to understand what’s happening, although that often leads to judgment, especially in the current economic and social climate. But as you said, care is more important. It’s hard to implement in daily life, not because we don’t care, but because it’s sometimes difficult to find the right way to care. For me, one of the first steps was listening. Listening to people with first-hand experience of things that, luckily, I don’t have to face, like climate migration. But it’s also about listening to other organisms. This brings an awareness of what people and living beings are actually going through. From there, we can begin to figure out the next steps. The more we know, the more it urges us to act. And then we just have to find the way to act that feels most appropriate for each of us.

SAK: You mentioned not only listening to other humans, but also to the more-than-human. How do you do that?

SŠ: Have you read ‘Quantum Listening’ by Pauline Oliveros? It’s a beautiful book, and I highly recommend it. She explores ways we can imagine what other beings might say, and understand the world, by slowing down, being present, and perceiving what’s happening around us. The living world speaks in tongues of scent, flourishing, rooting, burning and flooding. We can listen to it, and we can also imagine what more-than-human beings hum to each other. There’s something very bold about imagining things. Once you imagine something, you’re shifting something in your mind, aiming to make a difference.

Fragment of ‘445 Million Years Ago to Today’, 2023. Part of the mixed-media installation ‘To Be We Need to Know the River’. Solo exhibition view, Lot Projects, London. Photo: Chris Denoon

SAK: In terms of water, there is this slogan: make matter matter differently. It captures this form of communication very well. One thing is listening, but water also gives us the ability to communicate in the other direction. By doing something with our own water, the water that we are right now, we can communicate something, especially care or neglect, to other organisms. By just caring or neglecting our own matter, you can say a lot to the world. It does take a bit of imagination, but it’s also very tangible. Of course, if we want to do it the human way, we have to attach some meaning to it, and that’s where imagination plays a role. But at the same time, there is a direct physical message that we’re sending out every moment. What’s your message?

SŠ: I’m taking better care of myself. That’s for sure. Interestingly, I’ve worked a lot with topics like organisms and the elements that surround and inhabit us. But for some reason, this particular exhibition and these works have had the greatest impact. I think it might have to do with the fact that water is so common, and because of that it’s easy to grasp how important it is for water to remain clean. So my message is to maintain both metaphorically and physically clean water inside and outside our bodies.

SAK: That’s interesting. For me, one of the big success elements of hydrofeminism is exactly this possibility of affecting the world by acting on oneself. It might make it sound like a super-selfish and self-contained practice. But it is also empowering, as it gives the individual the capacity to make a difference. As you said, you have to start somewhere, and you start with yourself. In these terms, having an impact on the world means realising and acknowledging the long-term consequences of your local actions, working with yourself and the bodies that surround you.

However, being a body of water not only means that we are related to all the other bodies of water that exist right now. Water has a long history, and hopefully will have a long future. And as bodies of water, this is our past and our future. Adopting this perspective has had a huge impact on some people with whom I have discussed this. Especially in the context of understanding and coming to terms with your own mortality. By being a body of water and part of this hydro-common, we will never die.

SŠ: That’s beautiful. I must think about it.

Sabīne Šnē, ‘Tidal Tear Sediment’, 2025. Exhibition view at RIXC Gallery, Riga. Photo: Lelde Gūtmane

SAK: It’s one thing to realise that you have a direct impact on the world and take responsibility for it by caring. But it’s something even more intimate when you realise that that water just is you after you die, or maybe all that is left of you.

SŠ: I find this idea appealing for many different reasons. But mostly, it calms me in a strange way. Perhaps we shouldn’t delve too deeply into this thought: no one wants to think about their grandmother as a body of water while washing the dishes. But if you focus on the poetic notion that our bodies are connected to deep time, and that we will, in some way, live on this Earth in the future, it creates a profound existence. It gives you a sense of how small we are as beings, and at the same time, how intricately arranged everything is on the planetary scale of events.

SAK: I have to disagree with the point that we should not think about the dead while washing the dishes. I find this physical intimacy through water very powerful. I feel we should emphasise, whenever possible, that this water might be your grandma, to build a more intimate relationship with it, transmitting the way we know some person to water, our more-than-human companions, and the planet. Perhaps we should abandon our human-centered perspective. At the same time, that’s the way we know how to care and act, and one thing we can do is train ourselves to use the patterns we know from inter-human relationships or relationships with our loved ones to care for others.

I have always felt rather sorry that I’m not much into climate activism. Sometimes when I’m presenting on hydrofeminism, I feel I should be holding posters in front of the parliament instead, rather than debating it in academic or cultural circles. Because we still have the Baltic Sea and so many lakes and rivers, we just don’t appreciate the urgency sometimes.

SŠ: I agree with you about that feeling regarding activism, but I know myself well enough to admit that I’m not a person who will be on the front line holding a poster. At the same time, I support and admire those who do. But I disagree with your take on small-circle discussions. The more we exchange ideas and opinions, the more we move towards appreciating what we have, and finding ways to support those who are less fortunate. That’s the power of books, ideas and artworks, they offer a safe place where you can find something new and see the world from a different perspective. And then you can go back out into the real world and try to make a difference with this knowledge.

SAK: I guess we can all only do what we can in the best possible way. And if making a show about water is the way to go for you, then, I guess, why not?

Sabīne Šnē. Photo: Pietro Molinaris

Sofija Anna Kozlova. Photo: Kristīne Madjare