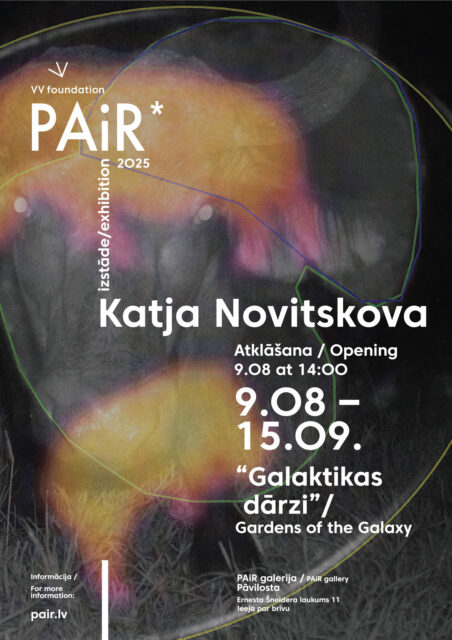

An overlooked opportunity exists in exploring femininity and its intersection with our relationships to the environment and society. While there’s a profound bond between women, nature and life itself, there is more to it than the simple trade-off of exhaust fumes for the scent of wildflowers: consider a ‘different’ world created by women from the very beginning, if you may. Drawing on the ideas of ecofeminism, and Marija Gimbutas’ goddess-centred theories, Roots to Routes‘ latest exhibition ‘Dryads of Cosquer’, curated by Merlin Taalumaa and Justė Kostikovaitė, envisions a world grounded in eco-reverence and feminine spirituality. The exhibition took place in Marseille as part of the Season of Lithuania in France 2024, and ran from 30 August to 31 October 2024.

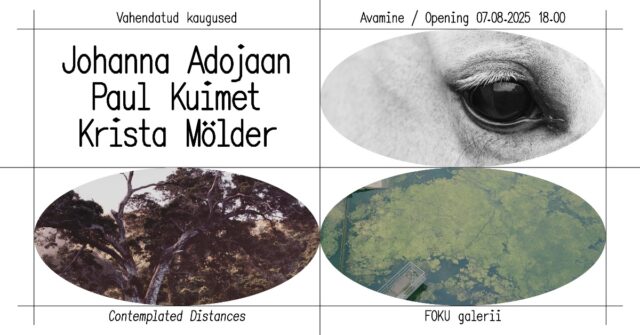

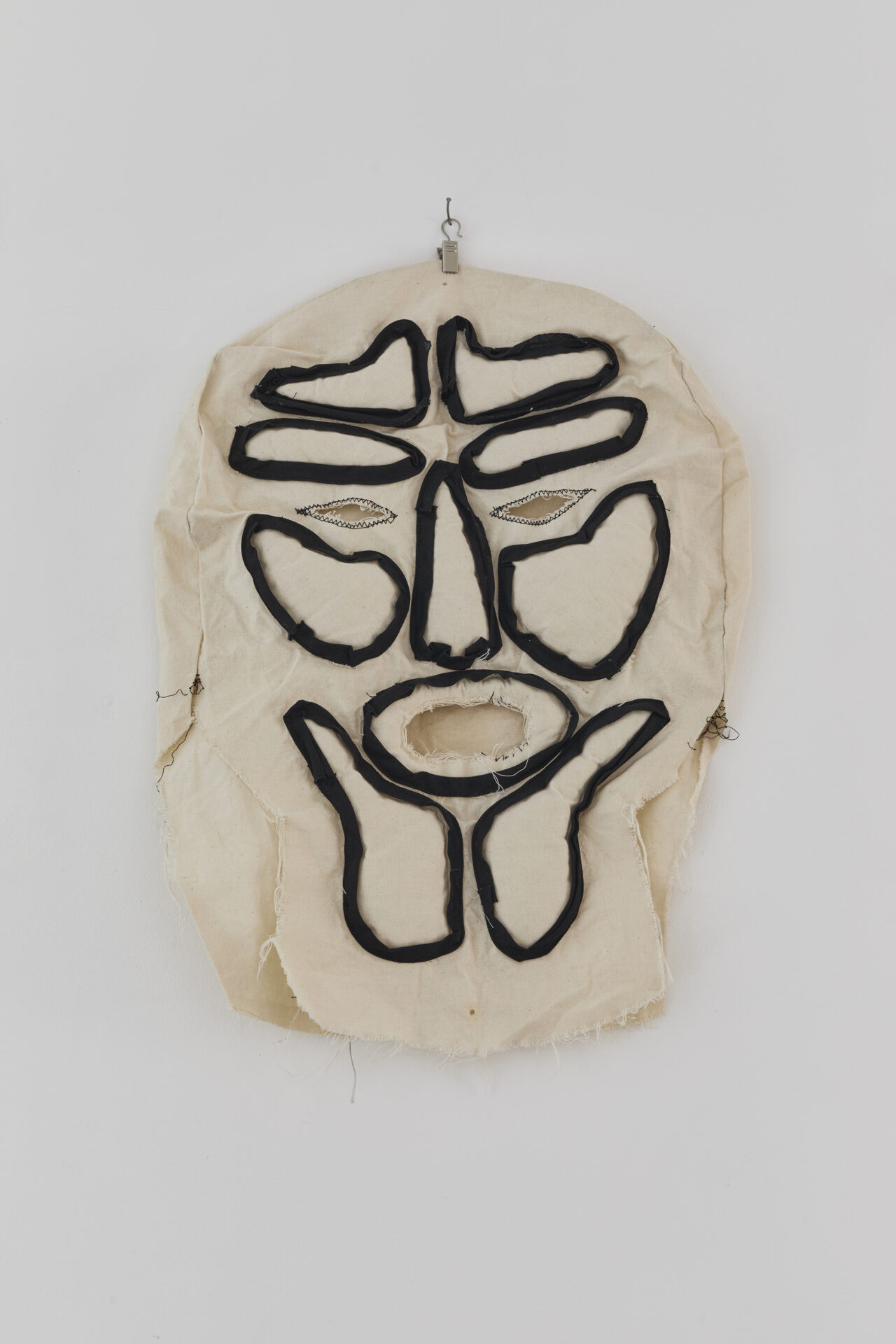

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, unfolds in a wash of soft hues and oceanic undertones. The artworks by eight international and Baltic artists, among whom are Lina Lapelytė, Morta Jonynaitė, Kristina Õllek, Evy Jokhova, Daria Melnikova, Nefeli Papadimouli, Darius Dolatyari-Dolatdoust, Adéla Součková and Tereza Porybna, harmonise seamlessly. This group exhibition evokes a sense of unity and cohesion, almost as if the entire exhibition is a singular, unified installation. The objects, which in a way have become water-friendly deities themselves, inhabit La Traverse, a gallery space just a stone’s throw from Malmousque Beach. Inside, the eggshell white walls, beige-painted details, and white mosaic tiles conjure up the sun-kissed coastal vibe of the region. The exhibition is a nod to the Cosquer Cave near Marseille, home to ancient art dating back over 27,000 years, now submerged beneath the waves. The atmosphere is strongly shaped by the bespoke wall paintings by Daria Melnikova, a Latvian artist whose work conjures up an ethereal underwater world reminiscent of the prehistoric Cosquer Cave.

‘The Goddess is not a separate being; she is the very essence of life, and all that exists is part of her,’[1] Marija Gimbutas.

In the context of the show, the artworks transcend mere individual expression, evolving into ritualistic elements that resonate with a collective vision. They serve as echoes of Gimbutas’ cosmology, reflecting the ideals of a peaceful, egalitarian, matriarchal society that might once have flourished in the Mediterranean, a civilisation the archaeologist referred to as Old Europe. The World in her Mouth, a title that alludes to photography by the artist Nefeli Papadimouli, positions the goddess at the centre, from where all creation flows. Each piece seems to converse with the next, weaving together a narrative tapestry that pays homage to an ancient world characterised by harmony and a deep reverence for the feminine. This dialogue extends the concept of our existence as ‘bodies of water’, embodying the notion that ‘to be a body of water is to be porous, to be fluid, to be in relation.’[2]

One cannot help but notice how this perspective might also paint a romanticised scene, firing the imagination. Would a world shaped by women truly be as peaceful and devoid of conflict as it seems, perhaps bordering on the utopian? It would be fascinating to explore the intricate layers of societies centred on female deities and the social tensions that might have arisen in these settings. While matrifocal, matrilineal and matriarchal systems might indeed offer alternative structures that empower women and promote an eco-friendly outlook, they were probably complex societies with their own hierarchies, conflicts and gender expectations. Discovering these dynamics alongside the harmonious ideals could reveal an ambiguous picture.

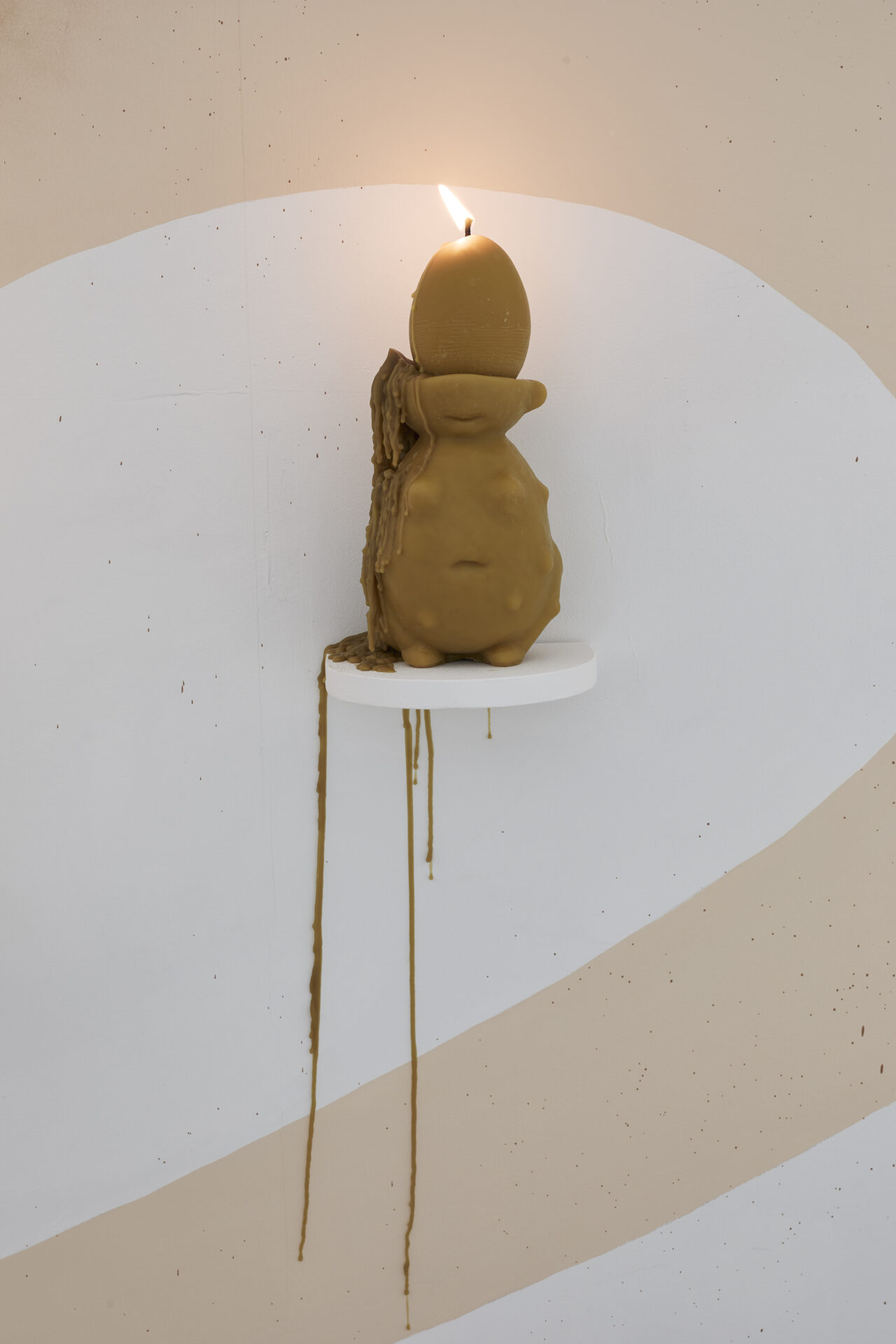

‘Dryads of Cosquer’ unfolds as an aesthetic exploration through a curated selection of new commissions and previously existing works that engage with the previously mentioned themes. Among them, Kristina Õllek’s ethereal, rosy-hued salt-riff paintings act as gateways into the aquatic realm. The shimmering surfaces of her inkjet prints are infused with sea salt harvested from the Camargue, creating a tangible connection with the sea. In harmony with Melnikova’s ceramic molluscs cradling ‘Baltic pearls’ of amber, and Morta Jonynaitė’s woven and knotted object installation, which echoes the Mediterranean’s presence, these works beckon the contemplation of oceanic ecosystems, reminding us of interconnectedness with the natural world. Adéla Součková’s 2024 collection of beeswax sculptures, entitled Mild as a Hedgehog, Staring as an Eagle, Stable as a Bear, beckons to traverse the boundaries of perception, nudging the consciousness towards a post-humanist landscape. These figures conjure up an ancient psyche that whispers from the depths of our evolutionary collective unconsciousness.

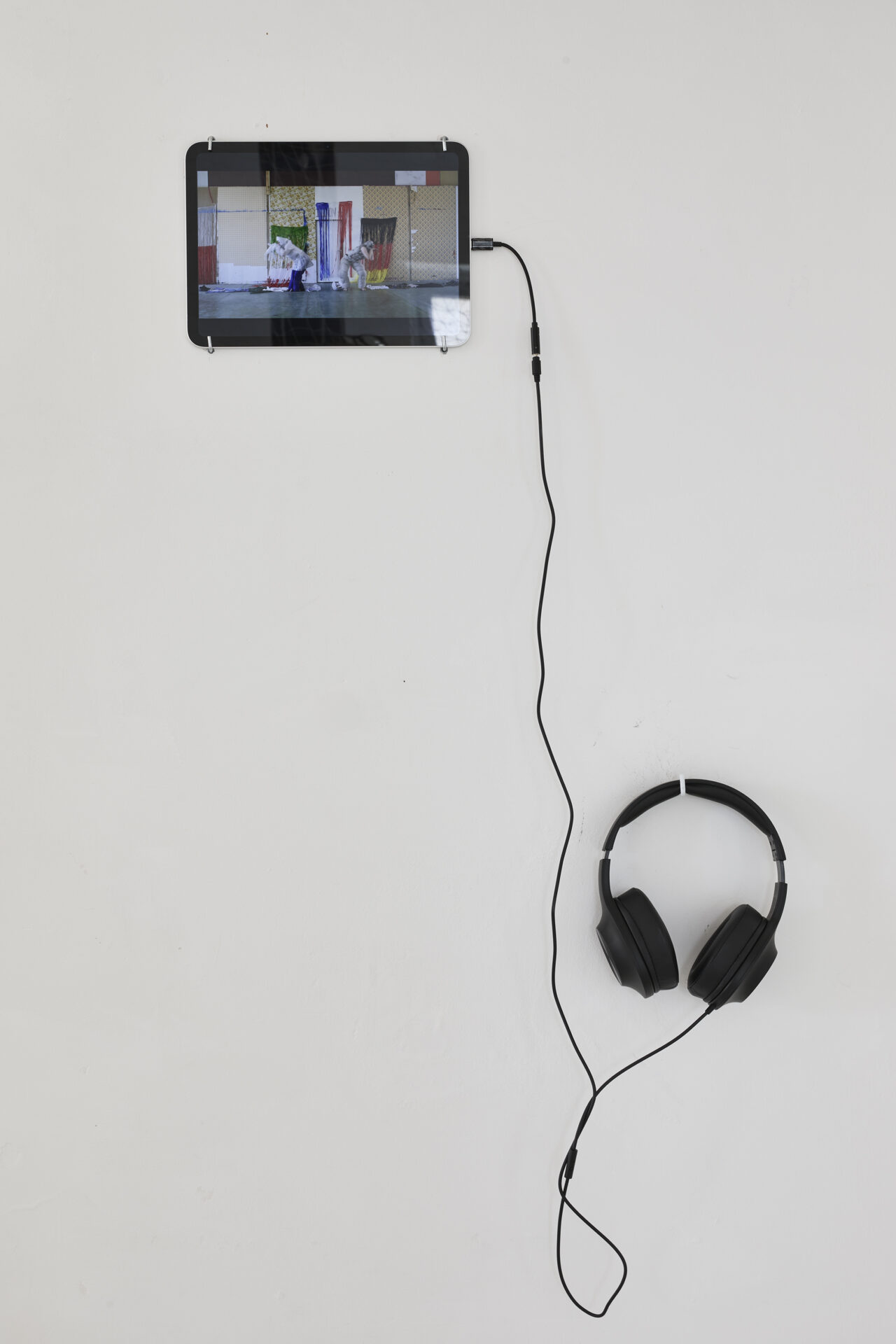

A striking contrast to the prevailing pastel shades emerges in Lina Lapelytė’s work. Her video installation provides a haunting reflection on the present, delving into the cycles of life, pointing to the loss of life and ecology. What began as a musical performance entitled What Happens with a Dead Fish is transformed into the video installation Ghost, showcasing a poetic meditation on water, presenting yet another dimension of her ongoing artistic exploration of the themes of vulnerability, fragility and decay. Lapelytė’s performances typically challenge audiences to reflect on their relationship with the environment, the absurdities of life, and societal norms, suggesting that what is lost is beyond full recovery.

The title of the exhibition encapsulates the intersection of myth and ecological reality. By pairing dryads (Greek goddesses of the forest) with the submerged petroglyphs of the cave, the exhibition fosters a dialogue between Gimbutas’ vision of a woman-centred egalitarian past and contemporary ecological crises. This setting evokes a hauntingly beautiful, Atlantis-like vision of what might have been or what has been lost. The goddesses may have existed for the community in precisely that way, leaving their positive traces on Old Europe as it was imagined; or perhaps they did not; the truth remains elusive. In this case the myth simply becomes a lens through which we can explore the potential for a more harmonious existence with nature. Feminist theorists such as Astrida Neimanis and Rosi Braidotti argue that mythological and cosmological frameworks are not mere relics of an imagined past, but can serve as generative tools for envisioning a ‘post-human’ politics that transcends hierarchical, anthropocentric world-views. ‘Dryads of Cosquer’ strove to unfold this theory in practice.

[1] Gimbutas, Marija. The Language of the Goddess: Unearthing the Hidden Symbols of Western Civilization. Harper & Row, 1989, p. 3.

[2] Neimanis, Astrida. ‘Bodies of Water.’ In Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology, edited by Astrida Neimanis et al., 2017.

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett

‘Dryads of Cosquer’, exhibition view, La Traverse, Marseille, 2024. Photo: Jc Lett