You are entering the space between myth and fairy tale, haunted by the curious and generous spirit of artist-cinéaste Kipras Dubauskas.

I first met Kipras and his moving image work in 2018, when the second artist-run photochemical laboratory was getting established in Vilnius. His film work is in a rich dialogue with his different media, human and non-human. He is weaving threads out of urban spaces, environmental interventions, world-building acts, performances, and sculptural objects, turning them into a playfully critical field of experiencing. The two 16mm films in this exhibition attest to a remarkable spirit, making his reliance on symbolic matter necessary.

Kipras’s artistic practice uses tactics of psychogeography, and the exhibition is best experienced in this light. Psychogeographers decode urban space by being in it, moving through it, exploring it and shifting the ways in which space can be read. Consider space as nobody’s and everybody’s, in an underground gesture, where the artist’s acts are critical of the whims of private ownership and curious about urban history. Abandoned buildings act as interfaces between ruining and rebuilding. Hidden infrastructures are revealed to question why we should experience life’s comforts as “natural” givens.

Genius Loci and ‘Firestarter’ are both bringing us into a series of experiences enacted by their author, based on impulses that are sometimes conceptual, other time based on gut-feeling. Using the concept of filotopia (a love of place) developed by the philosopher Arvydas Šliogeris, the artist is Setting place and inner feeling side-by-side. Then there’s the urge to go against processes of gentrification and permission, executed through the act of walking into zones of artistic interest. The films themselves recount these experiences, relying on the conventions of fiction (costumes) and creative documentation (montage). The adrenaline of trespassing is at the same time dampened and heightened by the filmer, who wants to safekeep a trace after his actions. This tension makes the moving image works expand beyond what is seen and staged, into the broader narrative of the artist’s life and daily practice.

In Genius Loci, the artist stages himself entering the Vilnius Heat Plant dressed as a municipal worker, climbing into the back of a truck. In the vein of the flaneur, we follow him drifting to a destination mostly unknown, carried by the urban flow. In Walter Benjamin’s anecdote of 1840s Paris, people would take their turtles for a walk to “set the pace for them” in order to claim the right to gentlemanly leisure. In Genius Loci, the artist’s gesture underlines the desire for making the city accessible beyond regulations. More importantly, his transgressive act claims our right to both space and pace within a private-property driven world order.

‘Firestarter’ begins as the documentation of St. Anthony’s procession somewhere in Italy, which soon turns into a quest within overlapping worlds, complete with tricksters, underground passages, and abandoned industrial sites. We are all entities with very important agendas.

A present-day re-incarnation of St. Anthony the Great emerges as the protagonist early on, but we are soon reminded of the unstable nature of cinema when the images begin to skillfully alternate between found footage, stop motion animation, cinema vérité, and scenes with non-actors. Props and settings, such as St. Anthony’s fire hook, gain a life and agency of their own. Abandoned spaces, polluted waters, and underground tunnels allow us to navigate the enchanted chain of events that make up the film.

The different layers of narrative carry associations in the artist’s personal mythology. The film refuses labelling by playfully avoiding a single story, a simple interpretation, or formal consistency. ‘Firestarter is a work of contemporary experimental cinema that is personal and subjective, yet fluid and free in its hybrid forms. Without completely abandoning a narrative plot, it allows the viewer to contemplate how meaning emerges from moving images, including the stereotypes of the saint and the pyromaniac. The cultural representations of fire are challenged and emplotted vividly. The priest brings the fire to the village community, only to end up causing damage. The phony and faceless art public, outraged when the Artist-Saint paints an image of fire over a neatly “framed” artwork. The toy firemen who put out the painted image with real water. The pyromaniac who sets an abandoned truck on fire, extinguished by a group of tricksters carrying flashing buckets of magic potion.

While these variations critically question representation, truth, and religious myth, they also acknowledge our need for a narrative, even if it is one of dissent. In our Lithuanian context, the male artist’s figure casts a long shadow. The winding dirt roads of experimental film are full of nomads with cameras, but most of them settle in other habitats eventually. The lineage of Kipras’s films may include, in my reading, the professionally amateur filmmaker Arturas Barysas, the documentary experiments of Audrius Stonys, but in equal measure moving image artists like Gintaras Šeputis and Tomas Andrijauskas, who begin to blend and blur film and video in the mid-1990s. Passing through the artists-run film spaces of Rotterdam and friendships with the informal gathering of the Tree Lab (2008-2012), Kipras’s carrying bag of film art is both wide and deep.

Let us celebrate this exhibition as a living argument for Lithuanian experimental film, standing at the spacious crossroads of cinema, art and life.

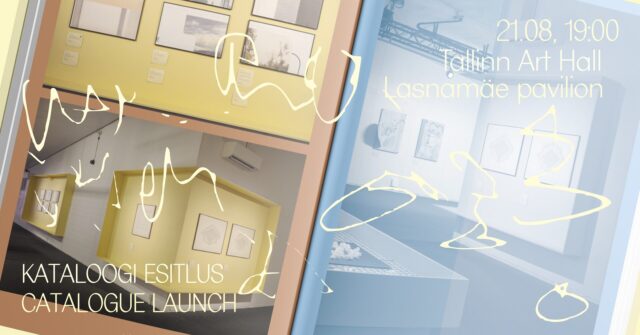

The exhibition ‘Firestarter’ by Kipras Dubauskas runs at the Meno parkas gallery (Kaunas, Lithuania) until 10 November.

The exhibition is part of Meno Parkas Gallery‘s project ‘Ether. 2024’. Project is financed by the Lithuanian Council for Culture.

Sponsor of the exhibition: UAB ‘GOTAS’ (Kaunas branch).

Photography: Airida Rekštytė / Meno parkas gallery