At the beginning of September, Sirja-Liisa Eelma’s personal exhibition Longing for lost space opened in the project rooms on the third floor of the Kumu Art Museum. Eelma is a minimalist conceptual painter whose oeuvre mainly deals with emptiness, silence and the relationship between the visible and the invisible. The initial impulses for the exhibition Longing for Lost Space were a sense of silence and timelessness emanating from 19th-century Biedermeier interiors, and the possible meanings and interactions between hidden and visible spaces. Eelma was inspired by the painting Interior of the Bluhm House in Tallinn (1841) by Carl Sigismund Walther, included in the permanent exhibition of Kumu. This Baltic-German painting is exceptional because it depicts with historical accuracy a concrete family and their house in Tallinn. Eelma conducted thorough research and a picture analysis; she also visited two flats in the building at 57 Pikk Street and recorded her findings. Brigita Reinert, the curator of the exhibition, talked to the artist in more detail about her creative work.

Brigita Reinert: What is your creative process like in general? Where do you find inspiration?

Sirja-Liisa Eelma: I am inspired by a yearning for beauty, emptiness and silence, a yearning for something that I feel is absent. It has changed over time. In addition to beauty, I have a need to crystallise some sort of sparseness and in-betweenness. In connection with inspiration, it requires discipline to come to the studio, and then things start happening. Practice feeds inspiration and that in turn keeps me working.

I see emotionality around me, lots of stories and details, colours, shapes and images. Occasionally there is too much of all this and fatigue sets in. I wish to create a space with no single clear image, colour or narrative, where one can be quiet and at the same time look deeper into oneself.

BR: Some critics have used such key words as “meditativeness”, “emptiness” and “aesthetics of boredom” when writing about your oeuvre. The more I think about your work, the more I think about it as “the art of silence”. Where does this interest in silence come from? Can it be said that, in the modern world suffering from information overload, you prefer silence and want to create a meditative state in the viewer, to clear the mind of excessive noise?

SLE: Yes, I strive for all of those things, but it is difficult for me to talk about it. For example, the expression “meditative silence” and the word “emptiness” are so heavily charged that they turn into heaviness. Everyone has so many experiences and associations with those words, plus some negative connotations. I would not like to be against anything. I’d rather be for something. That which I am for, or which I support, I think I can best express in painting.

BR: When you look at paintings, what do you observe and look for? What do you expect a painting to do?

SLE: I look for craftsmanship, but also simplicity and a certain sense of metaphysical timelessness. At a painting exhibition, I inevitably experience some sort of unconditional love. Paintings often bring about a physical reaction in me. I might, for example, feel an urge to start painting. The smell and feel of a painting, the presence of a mass of paint and the touch of the artist, the physical fixation of the image: all those things have effects.

BR: Do you think we can still speak of painters nowadays or should we describe them as contemporary artists who sometimes paint? How do you define yourself?

SLE: I like to think of myself as a painter, even when I am drawing, taking photos or making graphic art. I think via colours, pigments and oils, subtle and unambiguous proportions that are initially liquid and then become solid in particular forms. When I think of myself as a painter, I feel there is a link between myself and the people who painted before, and that the practice of painting and painters still exists.

BR: How did you come to painting? Are there any artists who have inspired you?

SLE: There was a particular moment in my childhood that led me to painting. When I was five years old, my father and I used to visit Aili and Toomas Vint every now and then. During one of those visits, I ended up in a dark corner of the corridor, and there was a door ajar that led to the studio. That smell, light and an unfinished painting on an easel: that moment was what I have been trying to recreate my entire life. Perhaps that is the room I have yearned to return to all this time.

BR: How is painting different from other media and what does it enable an artist to do?

SLE: Painting facilitates and also demands solitude. It is a truly direct, immediate and physical medium. I think that because there are so few hands-on art practices left, painting is becoming an elitist and special medium in the process of re-establishing itself.

In addition, painting takes time. It is a slow medium regardless of the style: even if it is expressive and fast, even if it is action painting, it is still time-consuming. The time spent is stored in the painting and it becomes available to the viewer. We seemingly get access to “more time” when we look at a painting. The time yielded by artists accumulates in paintings, which are like time banks. A painting gives its viewers a longer moment, like a gift, and it forces both the artist and viewers to take time off.

BR: Time is an interesting topic in the context of painting. How do you perceive yourself: would you say you are a slow and analytical painter? How much improvisation does your painting process involve and how much do you plan beforehand?

SLE: Yes, I like being slow: it enables me to spend more time in the company of a painting and to see things from a distance. I have therefore made certain choices that allow me to paint longer. On the other hand, as I deal with repetitions, I have acquired a certain proficiency, which means that it is starting to take less time to complete my works. In general, I would love to be slow, but occasionally my works are completed surprisingly fast.

There are some decisions I like to make before painting, to analyse and ponder for quite some time. Yet, a painting cannot be entirely figured out beforehand, even though I have a bit of an inclination to do that and an urge to start carrying it out at once. Planning needs to stop at the right time, i.e. at the moment when I feel an appetite for a particular image. I use an initial drawing in my paintings as a visual reference, but actual decisions are made in the process of mixing colours, and working with colours is very much intuitive.

BR: Your use of colour is nuanced, sensitive and considered. You have mentioned having read up on colour theory and the history of the colour pink, for example. What is your view of the role of colour in a painting?

SLE: What interests me about colour is delicacy and in-betweenness. I deal with reconciling and appeasing opposites. Even if I buy some rather exquisite halftone paints, I tend to mix them according to my own “recipes”. I experiment with coloured greys, in-between and changeover hues. When I’m applying paint to a large canvas with a small brush, I stand really close to the painting surface. I breathe onto the canvas and the painting becomes kind of animated and alive. At one point I started to consciously add “skin tones” to my paintings to express subtle corporeality.

I consider my choice and use of colour to be conceptual: I mainly work with colour as an image or an idea. Colour carries meaning more than anything else. In European culture, for example, the colour pink (the younger brother of the colour red, so to speak) used to be the colour of men and emperors. While we associate red with war, blood, Mars, fire and passion, pink was somewhat weaker but essentially the same. For a long time, pink used to be the colour of young men, but at some point it changed. Pink entered my paintings because of the association with the human body. Some colours on my palette are similar to make-up foundation.

BR: It seems to me that the world you create is occasionally truly tender, sensitive and one might even say feminine. Have you thought about it that way yourself?

SLE: Yes, to some extent I agree. I remember how I painted the series Emptying Field of Meaning: the series ends in three large black paintings, and all that cuboidness, squareness and angularity… the clear and rigid geometry and dark colours all turned out too strong and masculine. I wanted to escape that, so I started painting a series based on the art nouveau floral motif found on a floor tile at the HOP Gallery. I felt an obligation to visualise tenderness.

I have nothing against the differences between sexes: life is based on the interaction of opposites. Tenderness is intriguing when juxtaposed within the pictorial space with the vigorous and concrete nature of painting. I do not have a boudoir in my home, but when I paint, I have the liberty to use such aesthetics.

Sirja-Liisa Eelma’s exhibition Longing for lost space. Photo: Roman-Sten Tõnissoo

BR: Your paintings are often based on conceptual repetitions. How did you reach such a visual language, or where did this motif of repetition come from? Where does the appeal and the potential of repetition lie in your opinion?

SLE: There was a period in my life when I did not paint at all. I did not want to add to the volume of images, stories and pictures. Then, the idea of citing occurred to me: using already existing images or pictures or works of art, and by multiplying them creating more empty space or altered meaning.

Repetition is a fascinating and paradoxical phenomenon: it can emphasise a message, but at some point, it may change into a vibration or a rhythm in which the initial meaning is lost. Repetition enables me to be present in the process of painting for a long time. I do not need to worry too much about new situations and fast change-overs. I can stay in the moment and revive the process. I believe that repetition redeemed painting for me: it unveiled opportunities in painting which I still find meaningful. Repetitions create emptiness, and you find yourself like a thief in an empty room: nothing to steal, nothing to take with you, and no need to run away from anyone.

There is a photo of an interior captured at a metro station in early spring in Vienna when I was in residency there. Light is coming in through a window on the left and falling on a white wall. In 2012, I used this image in a series of 13 repeated works in various sizes. I consider that series to be the predecessor of my current painting practice. At the same time, I also realised that depicting reality did not satisfy me: I wanted to stage situations and environments rather than depict them. My painted structures and patterns tend to activate exhibition surfaces and spaces that surround them. If the paintings themselves take a step back and are visually delicate and quiet, they expose and highlight the space in which they have been displayed.

BR: Even if at first glance the works in some of the series seem the same when observed from afar, but they are all different and unique when examined up close. What do you have in mind as an artist when you occasionally introduce these minor or barely noticeable differences? Do you expect the viewer to take more time and be attentive when looking at your paintings?

SLE: This may seem like a paradox, but it is a case of a human error: a quiver of the hand or an impreciseness occurring in comparative orderliness. That is why I consider it important to use as few technical aids as possible which might facilitate achieving a flawless outcome. The charm of repetition and dissimilarity is just like each heartbeat or breath being similar and yet unique.

Images change little by little, from painting to painting, and series and exhibitions grow out of one another. For example, while painting a motif, I may start thinking of other ways to render it: altering a certain shade or creating a changeover. Dissimilarities also occur due to colour transitions and differently mixed shades. As I work on large series, I get to make small decisions and movements over a longer period of time. Each painting is a new thought or perhaps even a fraction of a thought.

BR: You have been regarded as a representative of Estonian conceptual minimalism. Johannes Saar has described that tradition nicely by saying that it is a movement “which primarily explores art’s capacity to evoke spatial illusions, serene mental states and abstract still lifes: elements that inherently defy simple translation into written form” (KUNST.EE 3/2023). What is your take on that? And what is important for you as an artist in your painting practice?

SLE: Yes, I just recently thought about that. Somehow, my students and I ended up talking about how Estonian art in the 2000s was conceptual and cold. That was the time when I reached maturity as an artist, and that period definitely influenced my oeuvre. As conceptuality means a certain thought-out decision, naturally I base my paintings on concrete ideas and deal with issues of meaning. On the other hand, intuition plays an important role in how the idea evolves and what aesthetic choices I make.

In Dolores Hoffmann’s monumental art classes, she told us about the way art is positioned in space: that no work is ever a lone vagabond, and that it should always be in some kind of symbiosis with the space that surrounds it. I have followed this principle as an artist, and some essential choices derive from it. I might also add that a work of art is placed in a certain conceptual situation or a mental environment.

BR: When you think about your journey as an artist thus far, do you feel that there have been any significant changes, shifts or reassessments?

SLE: The period 2003-2006, when I gave up painting for a while, was significant. Creating new pictures, images and narratives felt completely pointless. I was actively involved in other types of art practices at the time: socially relevant art projects and various cooperative efforts. I thought about painting without painting and about the withdrawal of art from the elitist gallery environment. I focussed on the meaning of a work of art as a visual marker but also as a broader, e.g. linguistic, signifier. My paintings displayed after 2006 in Vienna, the Tallinn City Gallery and the Hobusepea Gallery dealt specifically with language issues or, to be more specific, with the materiality and polysemy of words and letters. The birth of my daughter was another important event that triggered a change. It showed me very clearly what the measure of human existence was, and I realised that if I did not paint the pictures I was dreaming of, nobody would. Since my daughter turned three, I have purposefully been dealing with one specific “visual programme”.

Prior to 2003, my oeuvre was occasionally more colourful and depictive, but there has always been a fluctuation between depiction and abstraction, accompanied by a play with decorativeness, and this exhilarates me: flirting, for example, with the idea that a pattern and an ornament could also be a painting, etc.

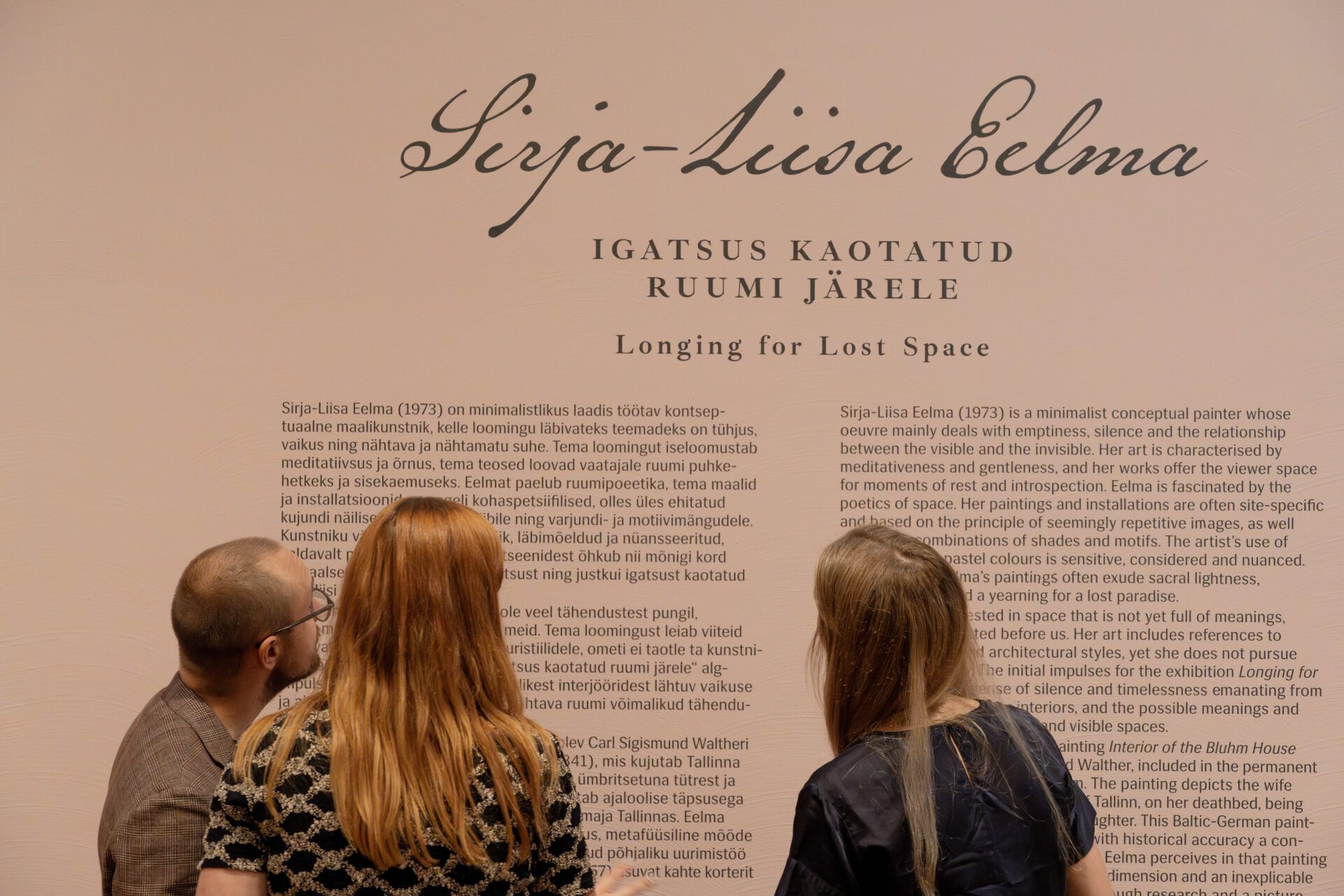

Opening of Sirja-Liisa Eelma’s exhibition Longing for lost space. Photo: Roman-Sten Tõnissoo

BR: Speaking of self-reflection, you have also used the mirror motif in your works on several occasions. Where did it come from and what does in mean in the context of your oeuvre?

SLE: Yes, I have indeed used mirrors on many levels in my works. I heard someone say that “mirrors in an art hall are bad taste”, and that is something that intrigued me: I immediately wanted to challenge it. At the exhibition Repeated Patterns (with Mari Kurismaa), I displayed one of my first paintings with a recognisable mirror motif. I have been using this image for quite some time in my oeuvre.

I have also thought about my own paintings as mirrors. A mirror is not a picture, but we always see a picture on its surface, and my paintings are the same: there is a lot of emptiness and/or suggestiveness and no unambiguous colours or images in them, yet on closer observation they reveal something in the viewer or in the surrounding space.

There is a parallel with the black mirror or Claude glass, which was supposedly first used by the French 17th– century landscape painter Claude Lorrain to paint the surrounding landscape. The dark convex glass harmonises and generalises the reflected image and tones down the colours. With the help of a black mirror, an artist can easily paint a rear-view image of a landscape. When Tiina Sarapu and I had an exhibition in the Draakoni Gallery in 2022 titled Black Mirror, for which we constructed dark mirrors of black and grey pieces of glass, the association with our contemporary version of the black mirror that we carry in our pockets every day – the mobile phone – became quite obvious.

BR: I have a feeling that your art in some ways hints at a hidden or invisible world, and there is a discernible element of holiness. The nature of this reality, imperceptible to human experience, that you refer to seems to be bright and lucid. Have you ever thought about transcendence or even sacrality in the context of your work?

SLE: It is obvious that as an artist I am not interested in (common) reality: it has already been created and I see no reason to recreate it. Let’s say that I depict a reality that clearly exists but is not visible until I make it visible [laughs].

I have thought a lot about how to speak of sacred and significant things without harming them with words, without doing a disservice to them. Things that cannot be spoken of directly could be spoken of in an abstract manner, via something else…. If there is a lucid sacrality in my works perceivable by the viewer, then I have accomplished my purpose.

Sirja-Liisa Eelma’s exhibition Longing for lost space. Photo: Stanislav Stepashko

BR: Tell me a little about the background of the Kumu exhibition. You found Carl Sigismund Walther’s work Interior of the Bluhm House in Tallinn at the permanent exhibition, and it inspired you. The work is said to be exceptional as it is one of the few interior paintings from that era painted in an identifiable building in Tallinn and depicting people known to us. Why did it inspire you so much initially and what have you discovered during the research that has fascinated you?

SLE: The painting caught my eye because of the silence emanating from it. The silky pink screen and the matching dress of the young woman caught my attention so completely that I overlooked the scene that the painting was depicting. The woman in the pink dress is Julchen von Haaks (Julchen Haecks), stepdaughter of the city doctor of Tallinn, Hermann Bluhm, and his wife Sophia. In the painting, she is handing a cup of tea or broth to her stepmother, who is lying ill in bed, and Julchen exudes mercy and lightness in the context of the gravity of the depicted scene, which refers to moving from one reality to another: Sophia Bluhm never recovered from her illness. The mood of the painting is, nevertheless, peaceful, not dramatic. I sense beauty and tenderness here.

The scene in the painting takes place at 57 Pikk Street in the Old Town of Tallinn. When I was preparing for the exhibition, I visited two flats there in which the scene could have taken place. I hoped to find a certain timelessness and get a sense of a room which existed before me: the room in which the scene depicted in the painting happened. Space is like a backdrop to the whole drama of life: it is something permanent in the continuous state of flux. An interior is a space, a model of the world. Not outer space, but a human-sized cosmos, a room in which, and a wallpaper against which, the drama of life unfolds, constant within the volatility of life. Some rooms existed before me and will go on existing after I am gone.

Windows in both flats face the back gardens and the walls of the opposite houses. My grandmother Salme lived in this neighbourhood, in Old Town, in Vene Street, and the windows of her flat also faced the back garden. I remember trying on a pink striped blouse with a ruffled collar in front of a mirror in my grandmother’s flat, and the mirror is placed between two windows, just like the mirrors in Walther’s painting. In the painting, the pink screen is reflected in the mirrors between the windows. There is a yearning in me to visit that flat in Vene Street, which since the late 1990s has not been in the possession of our family.

On the spot where the young woman in the painting is standing, the current owner of the flat has hung an icon depicting the coronation of the Virgin Mary. I feel as though I am witnessing a link between the times and the grand pattern of life. The Virgin Mary is crowned in heaven and she is our heavenly mother. She is always by our side: she was also by Sophia Bluhm’s side at the moment of her passing. I sense a metaphysical dimension in this interior scene, which is partly hinted at by the screen, which is used to hide something. Behind the screen there appears to be a door, symbolising a concealed passage to another side of life. This is what I look for in art: mystery and an unexplained silence, and capturing that in a picture is one of the most important things for me in the art of painting in general.

Sirja-Liisa Eelma’s exhibition Longing for lost space. Photo: Stanislav Stepashko

Sirja-Liisa Eelma’s exhibition Longing for lost space. Photo: Stanislav Stepashko

BR: Does this topic of death and evanescence also carry over to your works in the context of this exhibition?

SLE: I think I do not deal with death directly. I am more interested in timelessness or transcending time: how people who have lived at various times can experience situations that are in some ways similar. And I believe that death is not a negative concept. It is a secret, and we can believe it is beautiful and that after death we will experience unprecedented beauty we cannot even imagine with our limited earth-bound senses. For me, silence and emptiness are definitely not negative signifiers. I am amazed whenever they are treated in some context, even in a mundane situation, as negative. Multitudes, abundance or opulence exhaust me, and I find them difficult to handle, but emptiness and silence are manageable and understandable.

BR: A screen has been made for the Kumu exhibition on which paintings are displayed. Can you shed some light on the meaning of this particular object, and on working with spatial installations in your oeuvre in general?

SLE: I have had a few installation objects before which have either complemented the paintings or served as comments on them. They have not been very large: I have, rather, been engrossed in playing with meanings. For example, the object Cabinet of Decreasing Value, which was purchased for the collection of the Art Museum of Estonia, is a small object that is reminiscent of a shelf or a cupboard with sliding doors that fill the entire depth of it, so that its worth as a place for preserving something is questionable.

The object included in this exhibition is the largest object I have created thus far. The installation directly refers to the screen in Walther’s painting, but it deals with the art of painting in general, too: it reveals the back side of the painting, which is normally not visible to the viewer. The Walther painting is also displayed so that both sides can be seen. We can see the artist’s comments on the painting, the names of those depicted, etc. The issue of delicacy is also important here: a gesture that transgresses a rule or norm has to be carried out in a precise, firm and subtle manner, and it needs to have a strong conceptual basis.

Sirja-Liisa Eelma’s exhibition Longing for lost space. Photo: Stanislav Stepashko

BR: Your oeuvre includes references to different epochs and architectural styles. Some of your works have had depictions of elements from the architecture and interiors of surrounding galleries, for example. One of the main topics of the current Kumu display is engaging in dialogue with details of the interior depicted in Walther’s painting. What is it about spaces and interiors that fascinates you?

SLE: I mentioned before that I perceive space/interior as something that exists eternally. There is nothing eternal about interiors, of course, but from the perspective of human life and temporality we may think about them in this way. I am not interested in any particular architectural style or historical accuracy, but rather in the emptiness and silence manifested through spaces. I yearn for the existence of space itself, for an empty room, and I think that I am generally attracted to a sense of nostalgia and to using nostalgic elements or ornaments which enable me to travel from this day and age to somewhere in the past.

BR: What new topics and keywords do you see emerging at the Kumu exhibition? What are the thoughts and moods that visitors might pick up on?

SLE: Emptiness and silence, for which I have thus far not succeeded in finding better terms, have been permeating topics in my art for quite some time. And, as I mentioned, holiness or sacrality, which I have tried to represent and crystallise. Perhaps with the latter I have taken a step forward.

My last exhibition in the Tartu Art House dealt with the idea of superficiality, and I was satisfied with both the process and the outcome. Now, I have moved somewhere deeper, and although I am intimidated by an excess of meanings and prefer sparser semantic fields, because I wish to remain humble before great words, I sense that I have opened a box or a cabinet door that I can no longer close. I am very honest, open and a little frightened in the works at this exhibition. I would encourage the viewer to see invisible links and pictures in places where they cannot be seen at first glance.

Opening of Sirja-Liisa Eelma’s exhibition Longing for lost space. Photo: Roman-Sten Tõnissoo