Hildur Elísa Jónsdóttir is an artist, musician and composer interested in storytelling and creating engulfing experiences within spaces, often inspired by the mundanity of everyday life. In her works, she uses relational aesthetics and methods of institutional critique to interrupt and criticise normative narratives and show her subjects from a new angle.

Through a variety of media—performance, moving image, installation and music—Hildur Elísa employs normalised human behaviours and experiences critically, displacing them into an artistic context. By placing these mundane, everyday happenings in unconventional and absurd scenes, she aims to challenge the collective understanding of our heavily constructed social reality, reflecting on our ability to create new meaning and reforge reality, always asking ‘why’ and ‘what if’.

I met Hildur for a chat in her studio at SODAS 2123, where she is currently in residence. Against the roaring background of passing planes, we talked about delicate cakes of sound, the cutting silence of the 9 to 5 office and methods of turning grief into music.

Hildur Elísa Jónsdóttir. Photo: Bon Alog

Aistė Marija Stankevičiūtė: How would you introduce your practice?

Hildur Elísa Jónsdóttir: I usually work with music and performance, and I am constantly dealing with normative narratives. I think the way I approach my subjects is heavily influenced by Ármann Helgason, who was my clarinet teacher when I was a teenager. He encouraged me to look at the music I played from different perspectives and take time to enjoy seeing each phrase in a new light. He used to talk about music as a beautiful, delicious cake where playing each phrase was like taking a different slice out of the cake and carefully examining it and all of its individual ingredients from every angle before putting it back. Every slice is unique but together they create a tightly woven narrative; they form a unified whole, the cake. This idea, or way of thinking, has followed me into my practice today as well. I really enjoy isolating small details, flipping them around and examining them closely from every point of view until I find something interesting or unusual. Often, these are mundane, everyday things that have become displaced or distorted through the process, allowing me to see them from a new perspective. This act of ‘cake watching’ has truly taken over my mind.

AMS: That’s a very interesting way of thinking about sound, through this very material and edible thing.

HEJ: Yes, but we kind of eat sound. We consume it, it goes through us like food and if it’s particularly delicious, we remember it.

AMS: And you have this opportunity to choose your flavour every time, sometimes the cake goes bad… Is this image still guiding you through your practice?

HEJ: It is the North Star of what I do.

Fanfare, frequency of immediacy or núna strax. Photo: LNDW Studio

AMS: Your work is very detailed; now I’m starting to understand it even better, with this analogy of the cake.

You graduated from the Sandberg Institute with your artwork, ‘Fanfare’. What was it about?

HEJ: I was looking at everyday things around Amsterdam and I made performative compositions from them. I had a hard time getting into the final exhibition because I didn’t resonate with the space we were in; I don’t usually make material things so it took me a long time. I started looking into spatial interventions or ways of interrupting and interacting with the space, small explosions that would burst through the exhibition space once a day. I made three performances, each inspired by different aspects of the city soundscape. One was inspired by trucks backing up, one by the bike traffic in Amsterdam, which is quite intense, and then another one by ruminations from a stroll in the park. I wrote the performance inspired by bike traffic for a small ensemble of seven people; we were yelling things you hear in traffic and singing ambulance sounds, interacting with the space and the audience. I made everyone colourful costumes, almost a bit silly looking, just to make it not too normal, to flip the script a bit. Then there was one inspired by trucks backing up and women gossiping: in it, two women walked backwards through the entire exhibition space, holding a bag of flowers between them, while repeatedly singing a composition that mixes sounds of trucks reversing with a solemn hymn-like part. Each time before repeating the composition, they looked at each other and laughed in an unhinged way, suddenly snapping out of the lament-like chapter before resettling into the sound of trucks. For me, it was interesting to mix a feminine trait with the sound of something that isn’t stereotypically feminine, twisting this aspect with the laughter that gets gradually crazier throughout the performance, allowing the performers free reign to experiment and have fun with it. So even after a challenging beginning to the creative process, it turned out to be a really good experience.

Each piece had a very simple entry point—I was just looking at the city soundscape from different angles and being inspired by women carrying bags between them from the grocery store.

Fanfare, frequency of immediacy or núna strax. Photo: LNDW Studio

AMS: So you’re not really changing the natural way of how people live.

HEJ: I’m just extracting surprising elements from everyday things that people don’t usually look at or pay attention to.

AMS: Do you usually work with bigger groups of people?

HEJ: Yes, I find it fascinating to work with others and get them to perform for me.

AMS: It’s very much about trust, right? Is it the same group or do you change the people once in a while?

HEJ: It’s almost always a new group. Well, I do have my trusted ones I really like working with and keep inviting back. For example, in Fanfare, there were two people I’d never met before and I found it very exciting.

AMS: How do you start and guide yourself through the process to the final performance?

HEJ: I don’t sketch a lot, which has always been my Achilles heel. I might write down a couple of sentences or words but I don’t draw or experiment with materials. I’m not very good at this. Usually, an idea for a piece just pops up, very clear and detailed, and I know what I want to achieve and how to do it. But there is almost no process. It’s in my mind until it’s fully realised in front of me.

Maybe that’s why I bring performers in, to give me this twist because the process itself is so straightforward. When other people perform the pieces, they become something different. I lose control a bit and then it becomes more beautiful, not so ‘strictly mine’, as it’s interpreted by other people.

Seeking Solace – performed by Bryndís Guðjónsdóttir and Guja Sandholt

AMS: You’re adding different flavours to the cake!

Your other work, ‘Seeking Solace’, it’s about corporate life. Do you make connections with your own way of working as, in a way, you are the boss and there are different ways of guiding your team? Do you find something familiar in this corporate way of thinking and leading the group?

HEJ: I think it’s just something everyone can relate to. Life sometimes just happens to you and one day you have this mini reality check and realise ‘It’s been three weeks since I last checked in with myself’. That was the starting point.

I was working an office job during COVID. I managed a youth centre and I would have these imposter syndrome moments where I’d look very professional in front of two computer screens with Excel open in one and emails on the other but inside, I’d be freaking out thinking ‘Wow, people see me and think I’m something cool but I’m just a little baby, small and worried, afraid and scurried, and I have no idea what’s going on.’.

I got into TikTok during the pandemic, which is a black hole of material. But I also found it quite interesting that people are just scrolling on their phones, maybe at work, looking at these people online just baring their souls and sharing deeply personal confessions with the world. You don’t have this in real life. You sit next to someone at work but you don’t have these intimate moments with them, even though you see them every day.

AMS: Did the ‘Seeking Solace’ lyrics come from the office?

HEJ: Some of the lyrics were inspired by the videos I watched on TikTok, some of the lyrics came from me, but I’m also quite good at picking up what other people say, at collecting phrases.

Seeking Solace – performed by the Fóstbræður

AMS: Do you think your work can make a change? Of course, it does, even if it’s only a thought in another person’s head, but I mean…

HEJ: If I could break down capitalism with a performance? (Laughs) Well, that would be a dream!

For me, if a work resonates with one person that’s enough. I’m not doing this to change the culture of work and I don’t think people who are in charge of this culture would ever go see a performance like this. But I hope it at least shifts someone’s perspective or validates their feelings, allowing them to think ‘Okay, I’m not the only one who has absurd, intrusive thoughts.’.

I think this piece could also be set in artists’ studios, where people work independently in super organic and free-flowing spaces but are still having crippling self-doubts.

AMS: Your earlier work, Concerto for a Toy and a Pool, is the opposite of corporate—it’s playful and about leisure. Now, you’ve left the office and gone to the pool. Could you tell me more about this one?

HEJ: It relates very closely to the cake and looking at it.

I was thinking about quitting clarinet; I couldn’t continue because it was too much for me somehow, I wanted to do something more creative. Years later, I was thinking about classical music and how it has this definitive structure. At least the old classical music. Back then, I was living in Switzerland and I had done some German courses before coming as not everyone spoke English so I had to try my best to speak German and there was a month when I just sounded like a child. No matter which language I speak, it always comes back to the Islandic já (Eng. ‘yes’) and one of my professors thought it was so funny and kept poking gentle fun at me because in Icelandic we sometimes do it on the inhale.

Because Swiss German sounds very different from German, I started thinking if Swiss German is like a viola concerto, a bit darker and softer, and High-German is a violin concerto, very elaborate, fast and sharp, then I would just be like a drowning toy instrument, and that’s how I thought of the toy in a pool. In that piece, while performing on the toy instrument, I’m also struggling to stay afloat. My face has to be underneath the water but I can’t sink at the same time because I have to be able to breathe through the instrument, it’s a balancing game. But it really came from thinking about classical music retrospectively and this comment about language.

Konzert für Spielzeug uns Schwimmbad. Photo: Juliette Rowland

AMS: Is humour an important ingredient in your cake?

HEJ: Yes, very. But I also think this is how I was raised. There is something funny about everything, you take the cake and if you look at it from a certain angle, you’ll find humour there. You can see it in these moments or glimpses but it’s not necessarily there when you look at the whole thing. When you take it out of context, you can see that reality is absurd and everything is a bit surreal but you also see that everything is just what you make it. Nothing is real or set in stone, which I think is both a very relieving and important viewpoint; that nothing is unalterable.

For me, there must be humour in the work, without it necessarily being funny. If you look at it long enough, you’ll start seeing the humorous side of it but I’m not telling you a joke.

Laughter is also a natural response to uncomfortable situations or grief, or when you’ve been crying a lot, your body just defaults to laughter because it needs a break to soothe the nervous system.

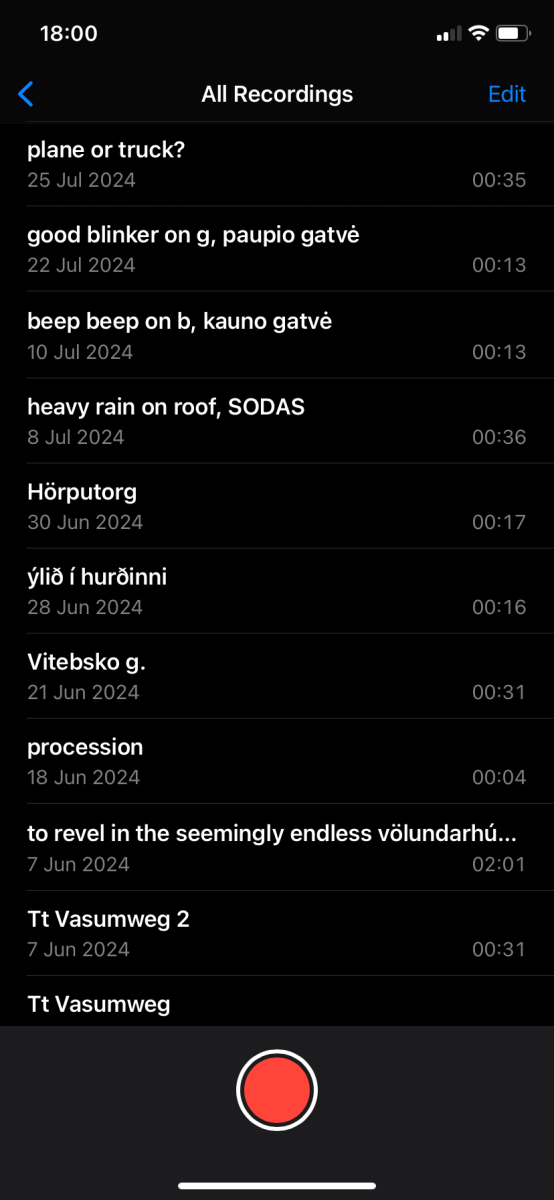

AMS: How do you save sounds? Do you have an archive?

HEJ: I make voice memos and record random things, like when the wind sounds good going through scaffolding or if I hear an interesting sound when out and about. I sometimes go back and use elements from these recordings; the chords or rhythm, or the texture of the sound. I have a lot of driving sounds and turn signals on my phone because that was an inspiration for my last piece.

I also use the Notes app a lot to write down what catches my attention. It’s important for me to lose the context sometimes—that’s why I don’t take videos and never record people talking.

Recordings. Hildur Elisa Jonsdottir screenshot

AMS: How different does Vilnius sound compared to Amsterdam, for example?

HEJ: I hear a lot more planes here, so many different aeroplane sounds! I’ve never lived this close to an airport before and I didn’t know they could vary; I hear like 13 different sounds. I hear a lot of cars, aeroplanes and parking noises crushing the gravel. As I’m awake at weird hours. some planes, especially at night, sound like old flying trucks. It’s very different from daytime traffic. While in Amsterdam, I hear more bikes and people walking.

AMS: Were you always this sensitive to environmental sounds? Did growing up in a small town have an impact on this?

HEJ: I grew up in Hafnarfjörður, a harbour town just outside of Reykjavík. The whole town is built on top of a lava field and I was lucky enough to grow up next to a big empty one near the ocean, so I was quite close to nature. When I was growing up, there was a maximum of 20,000 people living there. For Iceland, it’s quite big, but in the international context, it’s quite small. It took me 5 minutes to walk to the ocean. People would open their doors in the morning and let their kids out, who would then come back when they were hungry or when it got dark. There is a lot of freedom.

When I was a kid, I used to get very overwhelmed at school because it was so loud, to the point that when I got home, I needed at least an hour to chill alone before venturing out again. I didn’t even turn on the TV or radio, I just sat and read a book in total silence. So I was quite sensitive to sound as a kid.

It’s the same now; I like to have nothing on in the background, no music or anything. I think that’s why I like staying awake at night—everything’s so silent. The best hours are between midnight and three in the morning. I never listen to anything in these, just enjoy the absolute stillness. I quite like hearing my own thoughts, it’s very important for me to have this silent time for internal processing. This is the time when thoughts stand out and then it’s easier to catch them.

AMS: Are you working now on something specific? Do you have any upcoming performances?

HEJ: The theme of this residency is grieving and funerals. The general theme is festivity and I added the layer of funerals because it’s a theme I keep coming back to.

Grieving is such an interesting process, so versatile. It captures the whole human experience and is such a visceral thing to do. It’s a very interesting cake to examine.

This time, I’m looking for a way to translate funerals and grieving into sound. Also, I knew there was a strong sonic Lithuanian tradition regarding funerals, the sutartinės form, and that also fascinates me. The last time I was here I did a bit of research into it and went to a choir practice of this tradition. During my time here, I’ve been studying different traditions of laments and how the grieving process can be translated into sounds and compositions. I’ve landed on a series in which I try to translate the intimate nature of grief, mourning and the non-linear grieving process into short vocal loops. They’re titled hugleiðing i-iii, which can be translated as ‘contemplation’ or ‘meditation’, and consist of three distinct cassette loops that can be listened to individually and together, a bit like sutartinės. I’ve also started composing a piece for solo clarinet titled even if only as the clarinet is used in laments. It’s a fun challenge to write something for myself to perform on the clarinet; I’m excited to see what happens when I don’t have the added layer and comfort of another performer. I’ll present both of these pieces at A Night of Ascending Numbers, which will take place at SODAS 2123 on August 15 alongside works by my fellow residents Kirsty Kross and Mattias Hellberg.

In the studio. Photo: Bon Alog

AMS: Looking at our conversation and your work in a chronological way, we have work, leisure and death, with a cake for every occasion.

HEJ: (Laughs) Yes, I’m so interested in humanness, and the fact that we’ve created this reality everyone adheres to. Most of us take for granted that this is just the way things are and always have been but we made things this way. What if we took one step back and looked at it? I’m very curious about this man-made reality and how it fits human nature very well but simultaneously resists it. That creates very interesting tension points.

AMS: Yes, and when thinking about death and rituals, it’s so hidden.

HEJ: It’s become a taboo but death is such a natural part of life and in different cultures, more Western European traditions, death has become such a phenomenon; no one talks about it, it’s swept under the rug. While in Iceland, death isn’t that far away. Funerals, of course, can be very sad and they’re a safe space where people are allowed to show sadness but they can also be more a celebration of life than mourning of death. As a human being, I am just a temporary home for potential beauty and when my physical body will die, that beauty will go on to something else.

A funeral is such a loving thing to do for someone. Every time I’m at a funeral, the house is packed, everyone you’ve shared your life with is there. It’s not just sad, it’s also extremely beautiful. First, you cry together and then, there is a space to laugh together as well. Grieving is such a communal thing, you kind of can’t do it alone and it’s important to have someone who’s going through the same thing alongside you because then you can relieve and validate each other.

I’m interested in the softness and humanness of grief but not the mysticism of it. If you go through it very stiff and strong, it’ll most probably break you. That’s why doing it communally is so important as it allows the softness; it allows you to sway and oscillate back and forth depending on your needs. You need the softness to go through grief because when you’re soft, you can bend without breaking.

Hildur Elísa Jónsdóttir. Photo: Bon Alog