The recent exhibition, In the Name of Desire, presented at the Latvian National Museum of Art (LNMA) from April 27 to July 28, was the first attempt to retrospectively grasp the diversity of the themes of sexuality and sensuality in the history and present day of Baltic (but mostly Latvian) visual art. The text accompanying the exhibition emphasises the need to highlight queer art, ‘uncomfortable topics’, non-normative sexuality, the phenomena of otherness and desire, feminist strategies, critiques of the objectification of the female body, and also motifs of narcissism and fetishism. Bringing together such diverse sub-themes in a single exhibition is quite a bold undertaking, especially if one seeks to articulate it as a dialogue with classical art history, thus far dominated by a patriarchal heterosexual understanding of the sensual. The common denominator here is the concept of desire, which allows sexuality and sensuality to be considered in broad categories, evoking associations with a psychoanalytic interpretation of artistic images. However, even after repeated viewings and a careful reading of the curators’ comments, the overall message of the exhibition never becomes clear. Sexual themes and nude images seem to be merely collected without a clear conceptual backbone and almost every work invokes a different discourse of sexuality, with the ideas behind the exhibition branching off into many paths that never cross.

Dace Džeriņa. Liberation. 2002.

The team behind the exhibition consists of professionals from different disciplines. Līna Birzaka-Priekule has worked as a curator at LNMA for several years and is now head of the Office of the Culture Minister. Igors Gubenko is known as a philosopher, while Laura Brokāne has curated various cross-disciplinary cultural projects focusing on socially sensitive topics. This diversity of experiences and backgrounds presumably allows the team to eschew well-worn trajectories of curatorial storytelling, as well as expands the possibilities of perspective and interpretation with insights and methods derived from other disciplines. However, at a time when many are captivated by the position of authority held by the curator, one must also be aware of the risks inherent in assuming an ‘outsider’ perspective. In Latvia, the role of the curator is still often understood at the practical level of manager and producer or text author but, at the same time, another extreme is gradually emerging, where curatorial work is entrusted to public figures, intellectuals and opinion leaders who attract attention to a project outside the art world by virtue of their popularity. This trend risks de-professionalisation and the loss of professional standards as without knowledge of the internal dynamics of contemporary art, the results often tend to be naive. For example, generally known things may be presented as new discoveries and artworks may simply be misinterpreted or visually illustrating the concepts they’re exploring.

The curators of In the Name of Desire repeatedly emphasise the institutional importance of the exhibition venue. Commenting on the exhibition, curator Igors Gubenko calls it a continuation of the ‘institutional critique’ initiated by Elita Ansone’s curated exhibition on feminist art Just Don’t Cry! at LNMA in 2023. On one hand, shows at LNMA have so far been mostly oriented towards retrospective, canonising exhibitions and the cult of indisputable geniuses, whereas larger group exhibitions have most often been based on highlighting genre or stylistic phenomena without engaging with the insights and perspectives of contemporary theories in the interpretation of art. However, the overwhelming desire of the curators to bring erotic and, so they claim, taboo art into the museum is not a critique of the museum as an institution (not to mention that this is an inaccurate use of the term) but rather a confirmation of its importance; an institutional glorification of the museum. Do less common themes and phenomena really only acquire general value when they are exhibited in a state museum? Does this not exaggerate the role of the museum in the process of determining what’s valuable? Can this be applied at all to contemporary art, where institutions of a different format tend to play a much greater role?

View of the exhibition In the Name of Desire. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

View of the exhibition In the Name of Desire. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

Two other thematically similar exhibitions are taking place in the Baltics this summer and other museums, such as those in Berlin, are currently hosting several exhibitions on sexuality—Andy Warhol’s Velvet Rage and Beauty at Neue Nationalgalerie and Sex: Jewish Positions at the Jewish Museum—suggesting the topic is very current beyond the Baltics as well. In Tallinn, it’s Elisarion: Elisàr von Kupffer and Jaanus Samma at Kumu Museum, while in Vilnius it’s We Don’t Do This at MO Museum. In terms of vision, thematic framework and organisation, We Don’t Do This is almost identical to In the Name of Desire: three Baltic curators, Rebeka Põldsam, Inga Lāce, and Adomas Narkevičius, have created a chronological retrospective of the relationship between sexuality, society and art in Baltic art. While We Don’t Do This is more focused on the Soviet period and its post-socialist reverberations, In the Name of Desire is dominated by works from the past couple of decades and historical material is dealt with only episodically and often presented with an emphasis on how outdated it is.

In the Name of Desire begins with a wonder room (i.e. a cabinet of curiosities), comprising a rotating installation of sculptures created for the exhibition by the artists Hanele Zane Putniņa and Anna Ceipe. It consists of copies from the museum’s collection of classical and impressionist sculptural nudes, as well as representations of naked female bodies in the style of modernism and socialist realism. By marking these various works as objects aimed to satisfy the male gaze, the authors simplify the meanings that nudity, the body and the nude can have in art history. Moreover, neither this work nor the whole exhibition differentiates between nudity as an erotic object arousing sexual urges, as a means of exploring form or as an allegorical symbol of the values of antiquity (which also includes motifs of male nudity and homoeroticism). A more comprehensive discussion of the typology of nudity and an emphasis on its various meanings would be an important contribution not only to research on the subject but also to public education. This is particularly important as absurd censorship scandals over artistically ambiguous depictions have become a regular occurrence in Latvia. Interpreting any nudity as erotic, In the Name of Desire paradoxically comes close to the rhetoric of conservative forces that see sexual undertones everywhere.

View of the exhibition In the Name of Desire. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

Because of its thematic similarities, the exhibition at MO Museum unfortunately only highlights the shortcomings of In the Name of Desire, diagnosing wider problems in Latvian curatorial approaches and methods. The main difference is We Don’t Do This discusses sexuality and gender dynamics as a cultural-social phenomenon, while In the Name of Desire is dominated by physiologically literal sexuality, lacking broader cultural-historical contexts. We Don’t Do This explores not only the physical but also mental relations between sexuality and power in the field of visual culture, while In the Name of Desire focuses on the attributes of sexuality—nudity, pornography and genitalia. The exhibition at MO Museum searches for areas where the histories of sexuality and art intersect, encompassing well-known and revealing lesser-known art historical phenomena, while In the Name of Desire is fragmentary and centres on separate highlights (which are often intriguing), as if the overall direction of art history, era-specific aesthetics, visual discourses, cultural-political demands, and conditions dictated by taste and tradition did not exist. Successful retrospective exhibitions both highlight the unknown and allow us to better understand and notice new meanings in well-known history. Finally, while the curatorial methods of We Don’t Do This are based on research and theories of gender representation, those of In the Name of Desire operate with free associations and subjective interpretations. The use of theories is often arbitrary, based on the associations they evoke, rather than actually reading the artworks in new ways through this theoretical framework.

This impression is reinforced by the repeated misuse of art terms—for example, invoking ‘institutional critique’ to mean the introduction of themes hitherto alien to the museum or applying ‘aesthetics of the decisive moment’ to staged photography—which the curators seem to employ based on the associations they hold rather than their professional meaning. Consequently, the exhibition often contains glaring inaccuracies on the research level. The differences between the exhibitions in Riga and Vilnius are also inadvertently marked by their titles; the title of the MO Museum exhibition consists of a complete sentence with a historically specific reference, while the phrase ‘in the name of desire’ embodies the incompleteness that prevails in the exhibition. On the other hand, this indeterminacy can also be seen as a prelude to a larger future project that will continue the work this exhibition has started.

Vika Eksta. From the photo series P. 2019.

Rolands Kaņeps. Portrait of a Young Philanderer. 1984

In the Name of Desire is dominated by figural and figurative art, images and stories, and quite literal narratives. Metaphors and subtext which characterised, for example, the early contemporary art of the 1990s, are absent, as are conceptual art practices. In the context of 20th-century Baltic art history, photography was one of the main mediums in which homoerotic and heteroerotic narratives were expressed and this sphere is hardly represented in the exhibition. It is, of course, neither possible nor necessary to cover everything but the choices made here are not entirely convincing. Interestingly, the exhibition text puts a particular emphasis on its openness to new media and photography (according to the curators, this openness parallels being open to different sexual identities). First of all, the exhibition is actually dominated by traditional media; secondly, this formulation seems simply old-fashioned, with the curators themselves inventing a non-existent problem and once again emphasising the issue of form without explaining how the choice of medium can influence the content.

The selection of artists represented in the exhibition is also inconsequential and lacks uniformity. Several artists whose work vividly and consistently embodies the subject of the exhibition are represented only by a handful of works and disappear into the overall mass. This is the case with Andris Grinbergs, whose performances and videos from the 1970s not only included overt sexual acts but also served as a striking example of sexuality as an expression of individual freedom in opposition to the puritanism of Soviet power. The same can be said for contemporary artist Sabīne Vernere, whose work strives to observe female sexuality and record this observation, creating a radically new relationship between the subject and object of representation. In contrast, other artists who have only episodically dealt with the subject or whose role in the Latvian art scene is quite marginal are represented with a much larger number and volume of works. All in all, this creates odd accentuations and only further muddles the already unclear message of the exhibition.

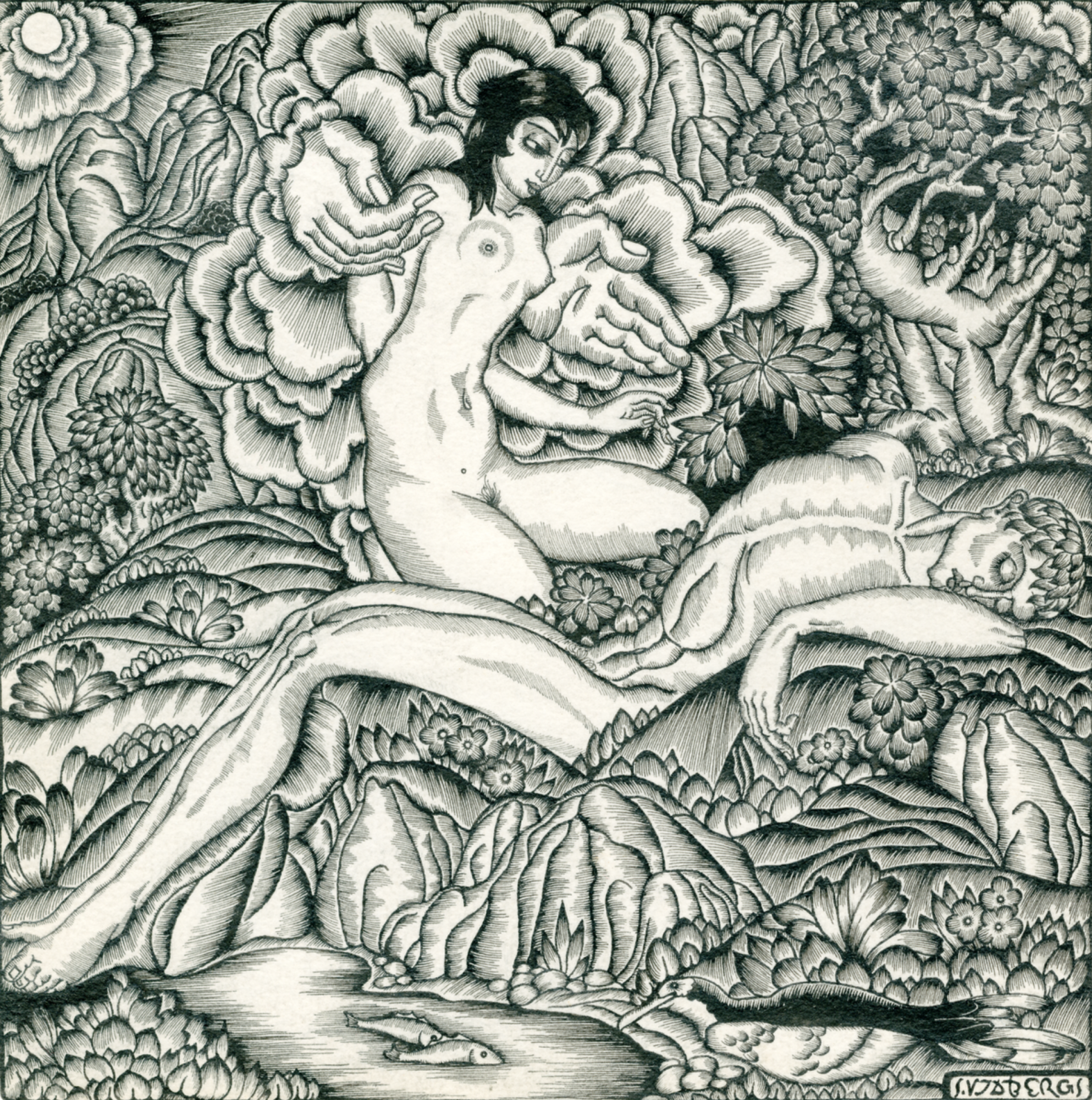

Sigismunds Vidbergs. The First People (The First People, Creation of Eve). From the series Erotica. 1918.

A similar problem can be observed with regard to historical material, with less expressive, even salon-like art singled out from a set of similar phenomena: the exhibition showcases Sigismunds Vidbergs’ prints from the first half of the 20th century while the queerly erotic self-portraits of his contemporary Kārlis Padegs would seem like a better fit; a soft-spoken allegory is picked out from Kristians Brekte’s scandalous oeuvre instead of his Madonnas of Rīga series dedicated to sex workers. At times, one ends up having the feeling that the curators, rather than highlighting the diverse and the different, are continuously focusing on stereotypes and are more eager to denigrate existing visual history than to create new versions and highlight the lesser known. This is not about privileging specific artists but rather about having a balance that fits the dynamics of the art scene and reflects the ideas and processes of art in relation to the bigger picture, its rhythm and direction, highlighting what is most important.

The show’s perspective on the representation of the female experience is also problematic, repeating stereotypes about women’s art as softer, more empathetic and caring. The painter Felicita Pauļuka is presented as the wife eclipsed by the fame (and the physical abuse) of her husband, the painter Jānis Pauļuks, and nothing more is said about her as an autonomous creative personality, thus continuing the rhetoric of the male genius. As part of the exhibition, Felicita Pauļuka’s 1973 nude Žanna II has been printed on the coffee bean packaging of the Kalve Coffee roastery, repeating the usual patriarchal capitalist techniques in which the female body is objectified for advertising purposes. However, there are also counter-examples in the exhibition, such as several works that represent the experiences of the LGBT+ community, including photographs by Veronika Šleivytė and works by Mētra Saberova, Anna-Stina Treumund and Mare Tralla. Interestingly, it’s women who have the strongest and most personal visual stories in the exhibition. Perhaps they are more memorable because they are not reduced to theoretical clichés, instead speaking about ‘other’ forms of sensibility and the vulnerability and fragility of sexuality through authentic experiences.

Veronika Šleivytė with Laura Andreskaitė, 1935.

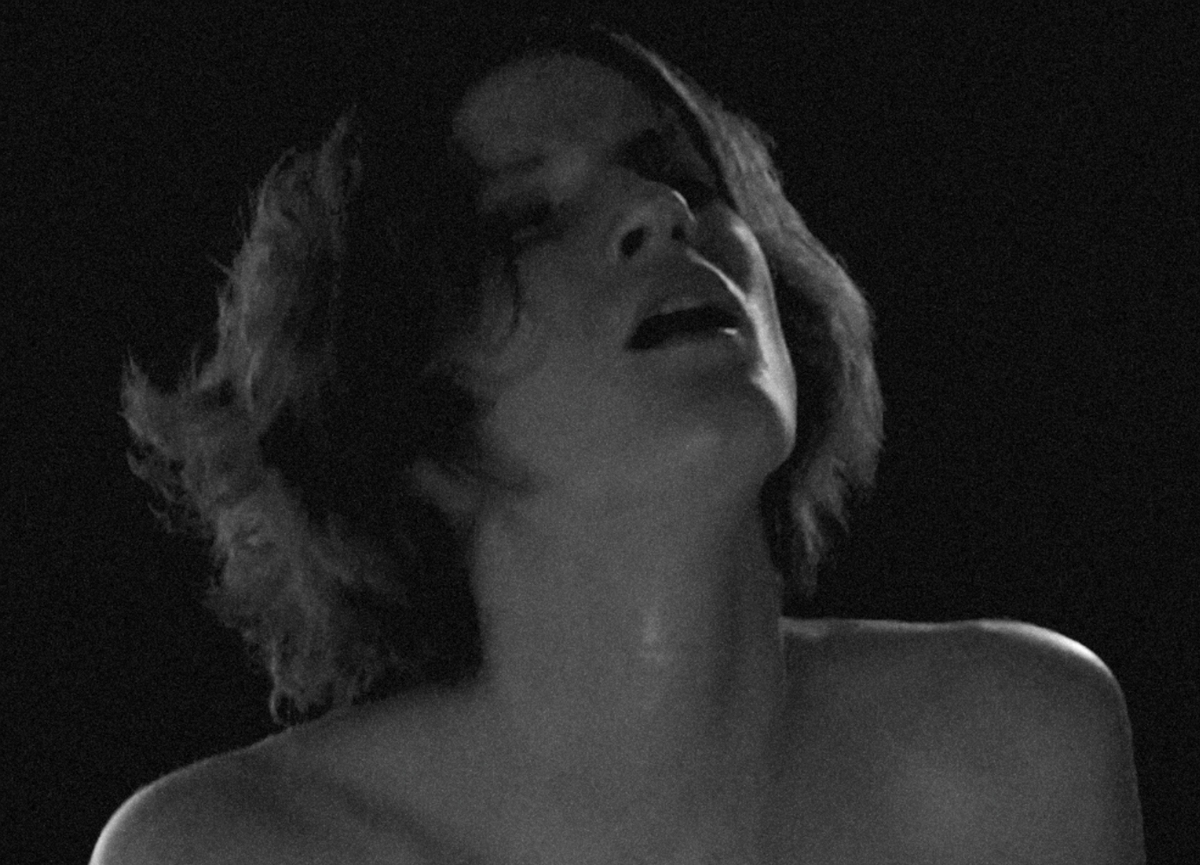

Anna-Stina Treumund. Gerda. 2007.

On the whole, queer desire is the most successful section of the show and probably the entire exhibition should have been dedicated to it, without the uncertain flings into the fields of normative sexuality. The same can be said about episodic turns to Lithuanian and Estonian art, which is only glimpsed in the exhibition. I fully share the artists’ view that artistic diversity goes hand in hand with broader human rights and the values of an inclusive society. Cultivating these values in creative processes is as important as in everyday life and that’s exactly why addressing socially sensitive topics requires an approach that is twice as sensitive and thorough as the handling of topics to which society is already accustomed.

View of the exhibition In the Name of Desire. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

Anna Malicka. Study of a Boot. 2024. Photo: Kristīne Madjare.

Anna-Stina Treumund. Princess Diaries II/ Who Wouldn’t Like to Be a Queer-Feminist Artist in a Post-Soviet Country. 2014. Photo: Kristīne Madjare.Madjare.

Anna-Stina Treumund. The Origin of One Possible orgasm. 2014. Anna-Stina Treumund. Die Hard. 2015. Photo: Kristīne Madjare.

Brenda Jansone. Shame. 2020. Photo: Kristīne Madjare.

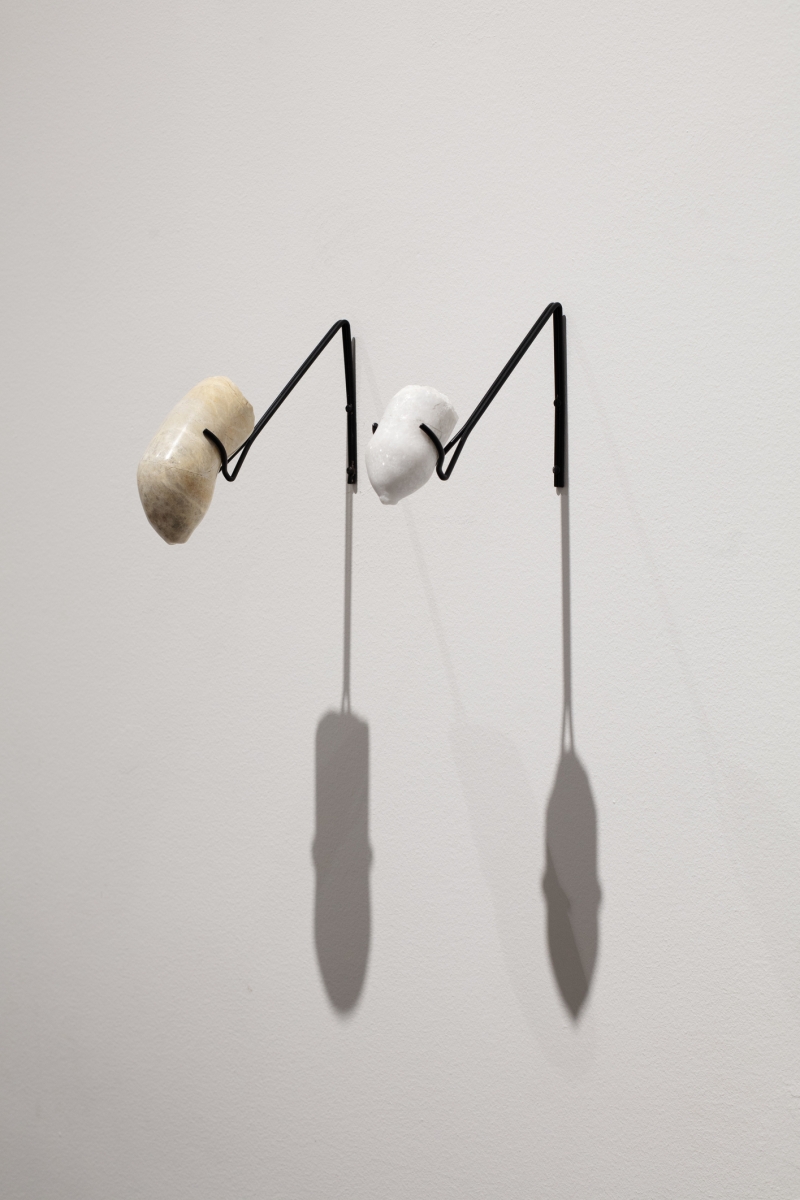

Daiga Grantiņa. Untitled. 2019. Photo: Kristīne Madjare.

Konstantin Zhukov. Black Carnation. Part Three. 2024. Photo: Kristīne Madjare.

View of the exhibition In the Name of Desire. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

Kristians Brekte. Pride. 2012. Photo: Kristīne Madjare.

Sabīne Vernere. SAVAGE. 2018. Photo: Kristīne Madjare.

Jaanus Samma. Pieces of Antiquity. 2020. Photo: Kristīne Madjare.

Vika Eksta. From the Photo Series P. 2019. Photo: Kristīne Madjare.