Sarah Lewis is a London-based filmmaker and interdisciplinary artist with an MA in artists’ film and moving image from Goldsmiths College in London. She works in the fields of the moving image, photography and installation, and her work has been presented theatrically, via broadcast, and in art galleries. She is a co-founder of the Ballpark Collective, creating opportunities for moving-image artists. Her work has recently focussed on the representation of female sexuality through trace and effect. She is committed to various long-term film projects that span decades: a process of intimacy that leads to creative outcomes. Her feature-length documentary ‘Cuts – No Ifs Or Buts’ was invited to Locarno Pro 2023 (Switzerland) where it won the Jannuzzi Smith and Le Film Français awards.

In this interview, we talk to Sarah about her latest exhibition and a moving image work of the same title ‘Bouffant’ at the InTheCloset space in Vilnius, touching on a 25-year documentary about a local Soho barbershop called Cuts, and the ability of hair’ to liberate and imprison.

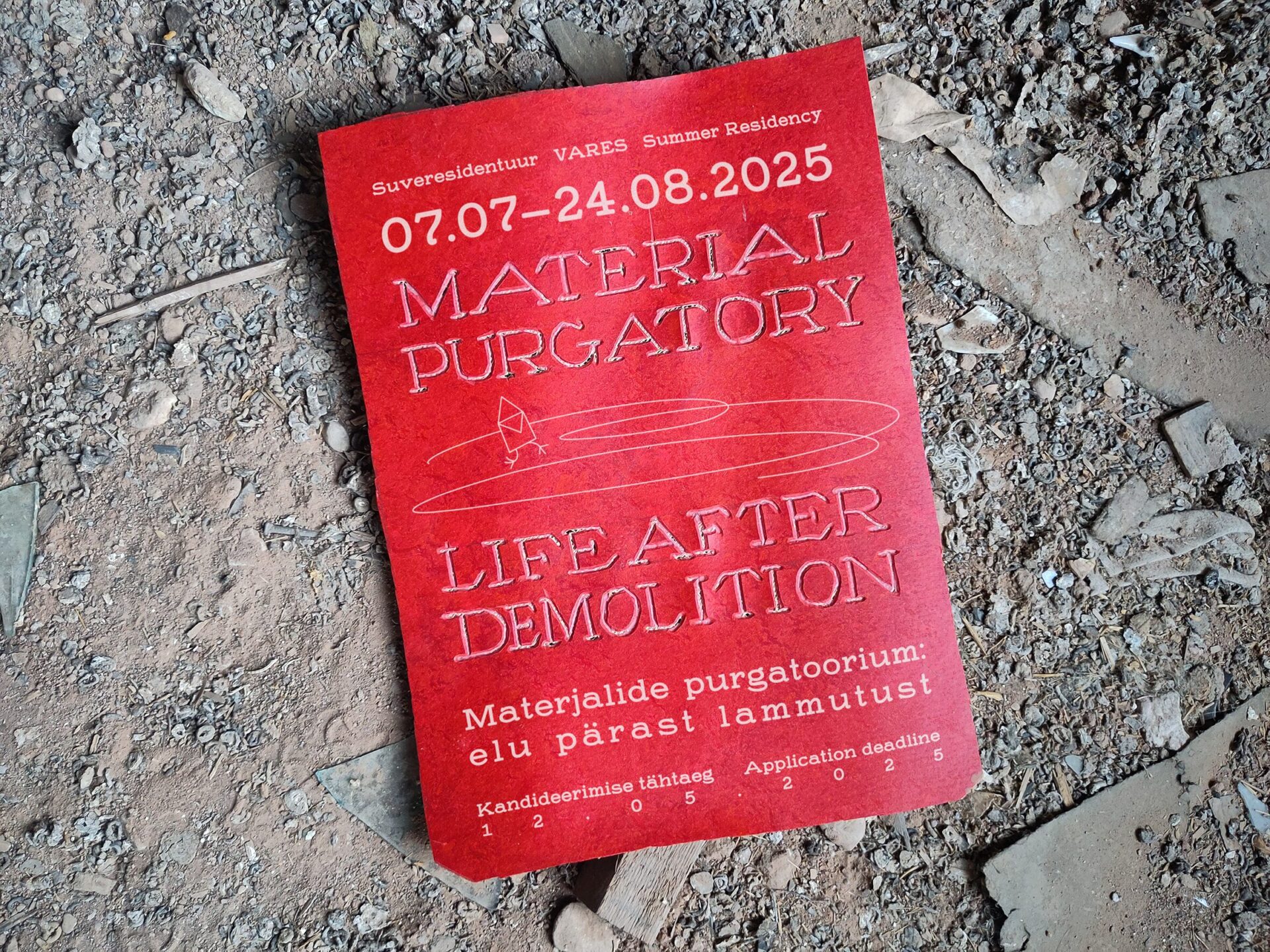

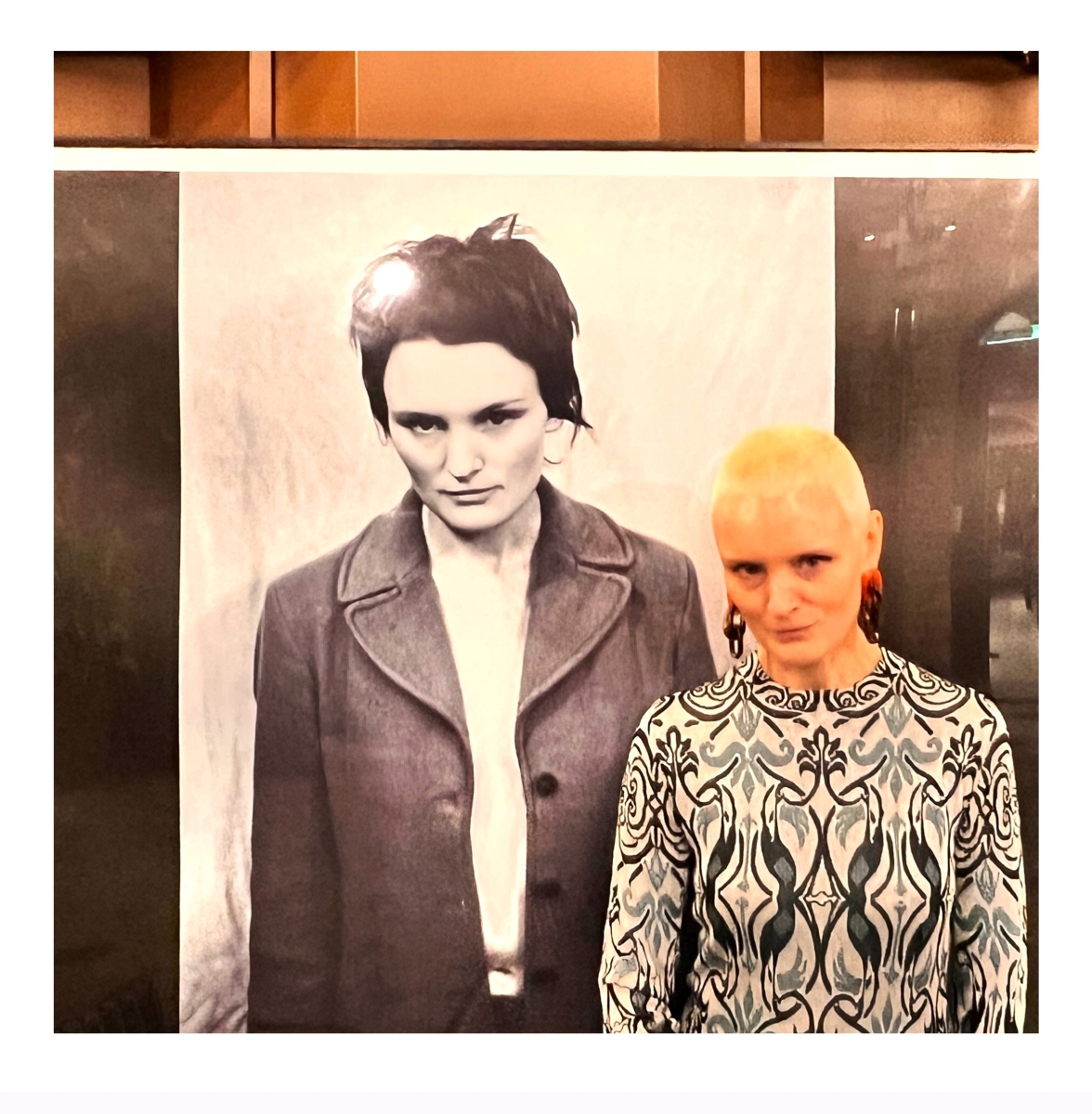

Photo of Sarah Lewis at ‘Cuts’ when filming the documentary in the late 90s.

Aistė Marija Stankevičiūtė: Sarah, congratulations on ‘Bouffant’! On encountering the French allure of its title, I envisioned something grandiose, voluminous and graceful. But what unfolded before me was a contradiction: pictures of messy hair, sculpted by the burst of desire, shone on a screen. Could you illuminate us on the enigmatic word bouffant? How did it get entangled with the hair of your work?

Sarah Lewis: The ‘Bouffant’ hairstyle is created by hair being backcombed on the top of the head to form a pile of tangled, loosely knotted hair. Unteased hair from the front of the head is then lightly combed over to give a ‘smooth, sleek look’. Usually, hairspray is applied to stiffen the hairdo and ‘hold it in place’.

In this work the idea of bouffant is a metaphor for the attempt to control the expression of erotic energy in a patriarchal society. What is underneath, messy and untamed is essential but obscured in the service of a stylised and presentable façade. The moving image work parodies the incessant swiping in the pursuit of finding the perfect persona to fulfil one’s desire, and yet this work consistently brings us back to what is underneath.

The experience of the erotic in my own life forced an impulse to record a trace. This felt urgent: a reminder of who I am, while simultaneously living in a culture that often ‘equates pornography and eroticism, two diametrically opposed uses of the sexual’ (to quote Audre Lorde). The intimacy of each encounter was captured by the image being ‘snapped’ by ‘the other’ on an iPhone.

I’ve talked about the underlying ideas behind the piece, but the idea for the work came to me when I had an intense experience of the erotic with my partner at the time: this experience made me realise the extent to which my own sexuality up until that point had been informed and distorted by the culture I had grown up with. Bouffant seems to trigger a recognition in women who see the piece, a secret knowing that subverts the culturally imposed dictates of the male gaze … and I love that because the idea of who is and who is not a ‘fuckable woman’ seems to be determined by these imposed tropes, and results in a reductive idea of female sexuality.

‘Nesting’. Photo from Sarah Lewis’ personal archive.

AMS: Hair holds inexhaustible traces of history, acting as a silent witness to the evolution of cultures and societies across time. It wields significant political power, often becoming a battleground for social norms, activism and rebellion. But it also curls with expressions of love and longing. If we look back to the Victorian era, for example, the erotic power of hair extended to the practice of exchanging locks of hair as tokens of affection, embodying intimate connections between lovers and friends through tangible traces of their being. And then there is another section of stories about mice living in tall and powdered 18th-century hairstyles, you scratch your scalp with a stick, and so on … This visual has stayed with me since history classes when I was thirteen years old. Anyway, it would be interesting to know how your relationship with hair started. You also delve into the roots of it with other means of expression, not only visual art, is that right?

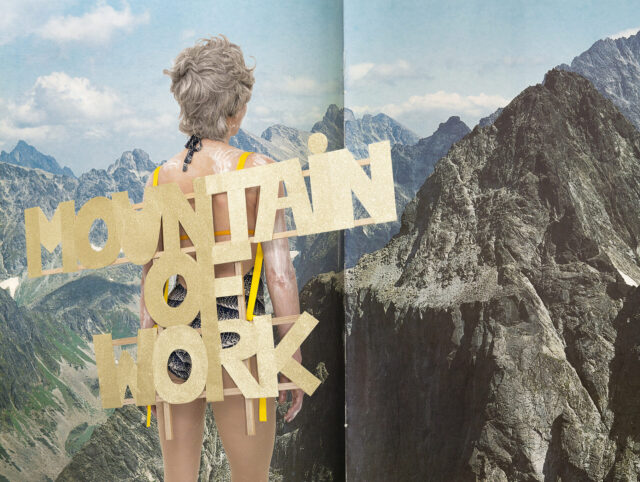

SL: Hair has been an ongoing preoccupation for me since I was a little girl watching how my mother’s identity was tied in with her ‘blonde look’. Over the years, I have also defined my identity by how I chose to wear my hair. Hair is tribal, it is expressive, and it creates community. As an artist, it has also been an ongoing preoccupation. I have worked with hair sculpturally and through my film practice. Over twenty-five years ago, I began making a documentary in a local Soho barbershop called Cuts. It was meant to be a ‘year in the life’, and I am only now completing the film. I was embedded in the Cuts community, who have built their lives around the ritual of cutting hair. The film is ostensibly about hair, but reveals many of the concerns that make us human. My work comes from a place of not knowing, a process that uncovers hidden meanings within my own psyche.

After many years of sporting micro bangs, I recently chose to shave off my shoulder-length hair. I remember waking the night before, terrified that I would look ‘abject’. This was the message that I had internalised about hair and female identity. What was really at play was my place in the world. I had defined myself by looking a certain way, and this in turn made others feel safe. What I was scared of was the loss of connection that occurs when someone no longer recognises the person they need you to be, the person they thought you were. It was a symbolic death, but it felt like a real one. What actually transpired felt like a new lease on life, a change at a foundational level, and with it, a new way of engaging with the world. The solidarity I felt with women was far greater than I’d experienced: women smiling at me on the street as if to say ‘good for you’, because we all intuitively understand that hair is power but it is also a prison.

Still frame from ‘Cuts- No Ifs Or Buts’

AMS: Have you ever thought about being involved in the haircutting business yourself? And returning to the film, could you tell us more about the process? Is it made of found footage, or did you film? With twenty-five years of research, I’m sure there is a lot of material.

No. There is a theme of hair running through my work, but hairdressing and hairstyles don’t really interest me. I was drawn to making the film about Cuts because I wanted to document the community: it was evident that it was a very special cultural hub that has existed in London since the early 1980s. What was originally meant to be a year in the life became a twenty-five-year-long project. I began filming on 16mm film in a pre-digital age with no concept of what was to come. As the process has progressed, the media used has represented the different times: filming on analogue through to iPhones.

My more personal work with hair has a different focus. Hair has been a symbol to gain access to certain preoccupations in my life that are too difficult to encounter directly: the process helps me work through ideas around female sexuality, the performative nature of gender, and resulting trauma.

AMS: Do you intend to work with the hair theme further? What else is on your horizon?

My work is not so strategic, ideas seem to come in whispers, and I’m open to the direction it takes. I’m currently working on a piece about care ‘giving’ and care ‘taking’, concerning ideas around mothers who use their child’s body to help alleviate their own guilt. I’m not committed to hair; whatever medium works for the idea, whether that be film, photography, performance or sculpture.

At the moment I’m in the final process of finishing my ‘Cuts – No Ifs Or Buts’ documentary! I have another film that I have been collecting footage for over a fifteen-year period based on the life of a South Sudanese child soldier David Nyuol Vincent and the French filmmaker Patrice Barrat: that is another long term project that I am looking to complete next.