It’s already past 2:30PM, which means I’m running late for the interview. I quickly leave Rupert’s office, descend two flights of stairs, and turn right to reach our first-floor reading room. marc is already there waiting, assuring me that my belatedness is of no concern. Sporting a baseball cap and dark-brown sunglasses, they are ready to face the piercing sun rays streaming down from the bright blue sky above the pine trees that encircle the area around Rupert. As we close the heavy metal doors behind us, I propose we take our conversation along the narrow footpath by the Neris river.

marc norbert hörler is a Berlin-based artist whose practice encompasses poetry, song, fragrance, writing, performance, education, and publishing. Combining language and the senses, marc composes spatial, sonic, and olfactory environments engaged in sensorial storytelling and diachronic allusions. Their work tends to engage with obscure histories, magical rituals, and somatic articulations – all of which offer an experience of new, emancipatory worlds.

Before I turn on the mic, I passingly ask whether marc has had a chance to do one of these (interviews) before.

marc: No, I haven’t really done many interviews. I appreciate that an interview offers a chance to elaborate more in detail about certain concepts, but also that it is a conversation rather than a catchy headline.

Photograph by Povilas Gumbis, Rupert.

Povilas: So, to get our conversation going, would you mind describing where we are?

marc: We are at what seems like the beginning of a forest next to a river. There’s a table, a trash bin. If I see a table like that, I assume that there’s a barbecue place somewhere. It’s similar to how I spent summer nights with my friends growing up in Switzerland: next to a river, somewhat surrounded by trees. Making a fire, talking and drinking wine.

Povilas: I, someone who’s never been to Switzerland, imagined that there’s a pretty big contrast between what you see here and what you see there. My image of your home country has a certain topographical drama to it: steep mountain ranges offset by deep valleys and vast azure lakes.

marc: Where I grew up it’s definitely hillier – mountains are visible and they always surround you. We didn’t have a river like Neris: I grew up with lakes or little streamlets. The landscape is mostly forest, meadows and farming land. And it’s a small community. The population of the whole district is like 15,000. And in my village, it was even less.

Povilas: This image that you’re painting – provincial community encircled by grand landforms – has a certain gentleness to it. I immediately think of one of your performances. In it, you, together with two other performers, traverse through a compact space, always finding one another through touch. Delicate strokes along the back; the head finding solace on a shoulder or thigh… All of this is offset by a distant background seen through a floor-to-ceiling window: a foggy landscape of Appenzell. It’s called Blue-something…

marc: spell for *bluescht?

Povilas: Yes, thank you. This gentle proximity of bodies echoes the harmonious use of language that is prominent throughout your oeuvre. There were many instances in spell for *bluescht where the performers would suddenly – sometimes mid-sentence – transition from German to English (or vice-versa). Could you elaborate on this seamless blend of vernacular and your general interest in language?

marc: I have a background in linguistics. I studied Latin and comparative linguistics and I think that’s also how I deal with language and poetry and voice in my work. Some of my research when writing a piece is working with etymologies. To observe how meanings of words change through time can be a helpful tool in understanding the dominant discourse at the time, and how it can suppress certain meanings in favour of others. The particular moments in spell for *bluescht where it’s shifting between the local dialect of my region and English is how I emphasise this oscillation between the lexical meaning of words and the materiality of the voice that performs them. The relationship between words and voicing has been a disputed one. What happens to words in their enunciation? Is the voice only meaningful when it pronounces the words so that the audience can understand them? Or maybe there is meaning to be gained by transgressing that in this excessive performance of the text. What happens to the legibility of the performance as a whole when the text that makes it up becomes unintelligible? The voice can completely transgress the textual and create other planes of perceiving, of listening, or perhaps reading in this case.

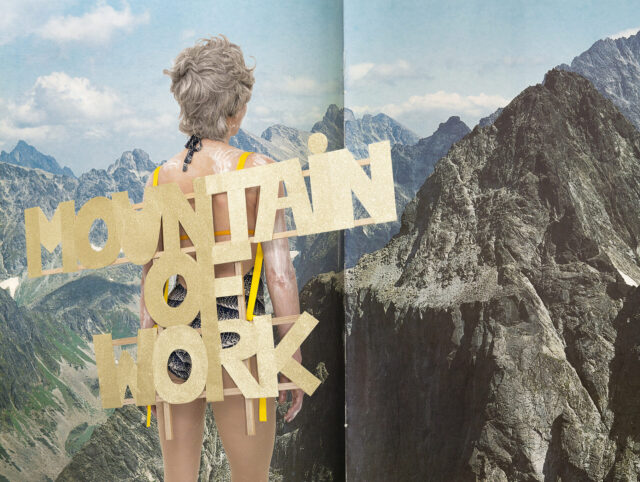

Still from heat and fervor (2023), performance, fragrance, sound, image courtesy to marc norbert hörler.

Povilas: What you’re now alluding to – this dialectical relationship that exceeds the sum of its parts – becomes noticeable through the many different yet coalescent elements that compose your performances. Apart from choreography, writing of the text and later voicing it, you also manufacture scents and make the garments both you and other performers wear. So where do you begin when you compose a new performance? Is it this singular from the very beginning?

marc: Generally in my process I’m working on a variety of different materialisations of my research at the same time. Poetry is one of them, working with scents is another. I carry these poems, sometimes melodies of songs, olfactory experiments with me for a longer period of time. I feel like only after a moment of these materials fermenting with each other a concrete idea for a piece starts to appear. I lay out all this stuff, and look at it again, and then I get a sense for which materials make each other vibrate and build up a tension in one another. These researches continue to exist and appear in more than one instance in my practice, new references open up. An example perhaps is the word ’smart’. Allusions to its story and relation to words like the German schmerzen (En. ’to hurt’) have appeared on multiple occasions. In a drawing that includes a poem on this, there is a sword, which in Tarot is a signifier of intellect; this is the second instance of an understanding of cerebral capacities as connected to sharpness and pain. I tried to look at this from a different point of view, a perspective of softness and a more interconnected understanding of the word, which then resulted in a huge knitted sword with a poem encrypted on its malleable blade.

Here, whilst continuing our journey on the circuitous trail, we are obliged to give way to the incoming traffic of bikes. This pauses our conversation for a bit.

marc: It’s funny that we saw twins, huh?

Povilas: Why – is that like a bad omen?

marc: (laughing) No, no. I like it because I see language and poetry as a form of spellcraft or magic and this reminded me of it. In an interview, poet CA Conrad said ‘Magic is discovering how things bend, then bending them for results […].’ And if you take a look at their poems, you can see that visually, they have a specific shape, kind of like a sigil, which carries its own meaning and potential. The poem is also a recipe, introduced by specific somatic rituals. And it is a score, so it can be performed. I like this encompassing understanding of poetry, it literally makes sense.

Povilas: You mentioned rituals, and they’re by definition collective. So is a poem, or any other form of cultural text, for that matter. The author’s intentions are met with the reader’s interpretations, resulting in a dialectic production of knowledge. Making sense, as you put it, is then always collaborative. Does that ring true to your practice?

marc: I understand the term ritual based on the assumed reconstructed root *re-, ‘to reason, observe carefully’. A ritual can then be both an individual or collective practice to reflect and understand something, to situate oneself vis-a-vis a multisensory reality. Ecologist David Abram would perhaps call this participatory, with regard to the reciprocity of perception. In touching someone or something, I simultaneously experience myself as touchable. I feel like such practices operate with this phenomenological understanding and thereby perhaps move from ‘the text’ to ‘texting’, if that makes sense, from the thing as an object to analyse to the score as a practice to do. This doing is infused with all the performers’ experiences and identities, and offers more than just an amplified bandwidth or increased harmonic potential.

Povilas: In the future, would you entertain the idea of going behind the scenes completely?

marc: I’d like to take on that role, yes, but I will continue performing myself. After composing some performances for several performers, I really enjoy seeing how a piece changes depending on the performers I work with and having to navigate the direction of it. Having another person perform some of what I’ve written also allows me to be affected by it in a different way. I like to imagine the characters in my performances as producing a slight friction with reality. A tension perhaps in a sense that it shows how things can be bent differently, to go back to CA Conrad for a moment. And it seems to me that this can create an opening, for imagination, for change.

Povilas: This bending of things and new openings you’re referring to – is your aim to create new, self-contained, and immersive environments?

marc: One of the terms that I like to think together with my work is world-making, a prominent concept in queer performance. Sometimes I feel like what is happening when different senses are activated in the perception of the piece is that it kind of reworks or twists those little nodes of time and space. I would say that this perceptive shift is what can work as an opening of sorts. I attempt to create environments that operate specifically with the activation of our ears and noses additionally to our eyes. Those two senses are very connected with the materialities of story-telling for me, and that’s something my pieces try to achieve, inside and outside of the written score.

Povilas: And what are the foundations for the worlds that you make?

marc: As a queer person, my practice is sensitive to those experiences. In my latest performance for heat and fervor, it became very apparent that apart from the content of the piece, the experiences of that shared process and the emotional ties between the performers become part of the performance as well. I would like to see my performative practice as a testament of that process too, as an affective potential for interaction and collaboration. The piece I’m talking about worked specifically with the choir as a social and material coming-together of voices, which informs what world-making can mean in this context. I’m also thinking of the ephemerality of performance, of enunciated language and smell. Especially the way fragrance works with memory is relevant for me. What is the relation between performance and memory? The performance continues to live on in affective shards, at times literally in molecules that stay in one’s nose after leaving and that can be activated at random and potentially transport you right back.

Povilas: If, as you say, memory can activate the performance, can the latter also do the same for the former? Here I’m referring to your use of folklore and its wealth of narratives or collective memories that you revitalise in a contemporary context.

marc: I’ve been working with folklore as an aesthetic and practice to reclaim, one that I grew up with but that never felt like it was part of me, or I was part of it. Folklore as popular knowledge, customs, beliefs are things that are a big part of what I grew up with. I wanted to work with these inherited cultural and aesthetic forms and redefine my relationship to them by claiming them in my work and turning them into something else. In The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, writer Ursula K. Le Guin quotes anthropologist Helen Fisher: ’The first cultural device was probably a recipient, […] a container to hold gathered products and some kind of sling or net carrier.’ My understanding of story-telling and how I use it in my work is related to how Le Guin understands her writerly practice, one that sees the various things that are held in such a container but also the relation they take to one another. I think there is a very intimate relationship between performance and memory. But memory perhaps not so much as something coming from the past, but memory as the potential sensory souvenirs taken from the ephemeral shards of reality that are displayed. As something yet to come.

Photograph by Andrej Vasilenko @ Articulations 3, Medūza, 30 August, 2023.

Povilas: Do you think that all of these ideas are retained within the documentation of you work? Smell, such a prevalent element in your performances, escapes the recording capabilities of a camera…

marc: I find inspiration in the writings of queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz. One of my favourite texts is his essay Ephemera as Evidence: Introductory Notes to Queer Acts, in which he talks about queer acts as standing as evidence for queer lives, powers and possibilities. I think by now I can almost quote verbatim what he writes about ephemera: ’Ephemera, as I am using it here, is linked to alternate modes of textuality and narrativity like memory and performance’, and he continues by saying that ‘it is all of those things that remain after a performance, a kind of evidence of what has transpired, but certainly not the thing itself. It does not rest on epistemological foundations but is instead interested in following traces, glimmers, residues, and specks of things.’ So perhaps the afterlife of the performance is not to be captured and preserved – at least not in an official, document-oriented archival way. So even though, yes, I can make a video, it does not manage to preserve the performance entirely. Perhaps the thing it most directly evidences is that the performance happened. I can prove it in my portfolio and on my website. The afterlife of the experience of the audience in the performance is probably many things but a clear image; more of a feeling, perhaps a fragment of a melody, or a fragrant memory.

Povilas: Roland Barthes argued that a photograph’s sole claim to veracity is by being a ’testament to the existence of a specific thing in a specific place at a specific time.’ But even here he leaves space for specks of trace – he doesn’t annihilate the connection between the action of conception and the material consequence of that action.

marc: It’s interesting then to think about how to continue a performance in how the visual material that documents it is treated. I guess that also reframes the question of the archive. Is there a way to have a sensorial access to something like an archive? How does that change the way things like performances are documented, so that it speaks the language of immersion or being with the performance rather than outside of it?

Povilas: So how do you edit a video of your performance, for example? Undoubtedly, you put a lot of care into choosing when to cut, what sort of angles to showcase, etcetera.

marc: This is the point where I collaborate with other people. The invitation to have someone work on it and bring in their own experience of the work may already introduce aspects of the work itself rather than enacting a gaze from outside. And for this I need to be able to provide them with the same care, and have the means to compensate them in a way that facilitates an openness to such a process.

Povilas: Since we’re almost back at Rupert, I thought at the end it would be fitting to ask you what’s in store for you in the future, what could we exp–

We suddenly hear a loud thud nearby. In front of us, a car, slowly crawling out of its parking spot, has drove on top of a sidewalk, hitting it in the process. An irritating noise of now loosely-hanging front bumper scraping against cement is what follows. Since we are directly next to Rupert, this feels like a ‘full-stop’ moment signalling to us that we have reached the end of our conversation. The question of marc’s future will thus be left unanswered. However, smidgeons of past and present dispersed throughout the interview will, hopefully, inspire the reader to follow marc’s artistic journey. As a little nudge towards that direction, here’s a link to their website.

Povilas Gumbis is an art historian interested in Eastern European and Baltic art of the 20th century, their post-soviet developments, resulting historiographies, and the contemporary scene. Presently he works at Rupert.