It’s one of those early mornings that acts as a forewarning for the approaching realities of Autumn. The lingering possibility of rain and the presence of sharp gusts of wind make the outdoor environment unwelcoming. Hence, Amy Watson, a South Africa-based independent curator currently in residency at Rupert, and I decide to occupy Rupert’s office space for our interview.

As the director of POOL, Amy runs a dynamic, collaboration-based art institution, currently located in Cape Town. This emphasis on collaboration and interdependence informs all of her curatorial projects, including her most recent collaboration wherewithall, a library of equipment, practical knowledge, research and knowledge exchange that supports an ecosystem of independent practice. In Amy’s independent curatorial work, a recent exhibition How To Disappear looked at the role of surveillance within contemporary society, considering how these technologies might be turned towards forms of collective resistance. Even this interview could be added to the above list of examples of Amy’s collaborative approach. Having prepared to inquire about her past and current projects, I’m instead led down the path of Amy’s present-day fascination with modernist spaces of Vilnius: an interest which – and this she knows quite well – coincides with my own research. What follows is an opening into the practice of a curator in real time: brainstorming ideas, applying them to specific spaces and their histories, fusing it with more nuanced theoretical discourses, and, finally, considering the practicalities.

We start our interview even before taking our seats. As we continue to get enveloped by the conversation, the drabness seen through the office windows quickly dissipates. So does my competence as a journalist, as only 10 minutes in do I realise that I haven’t started recording.

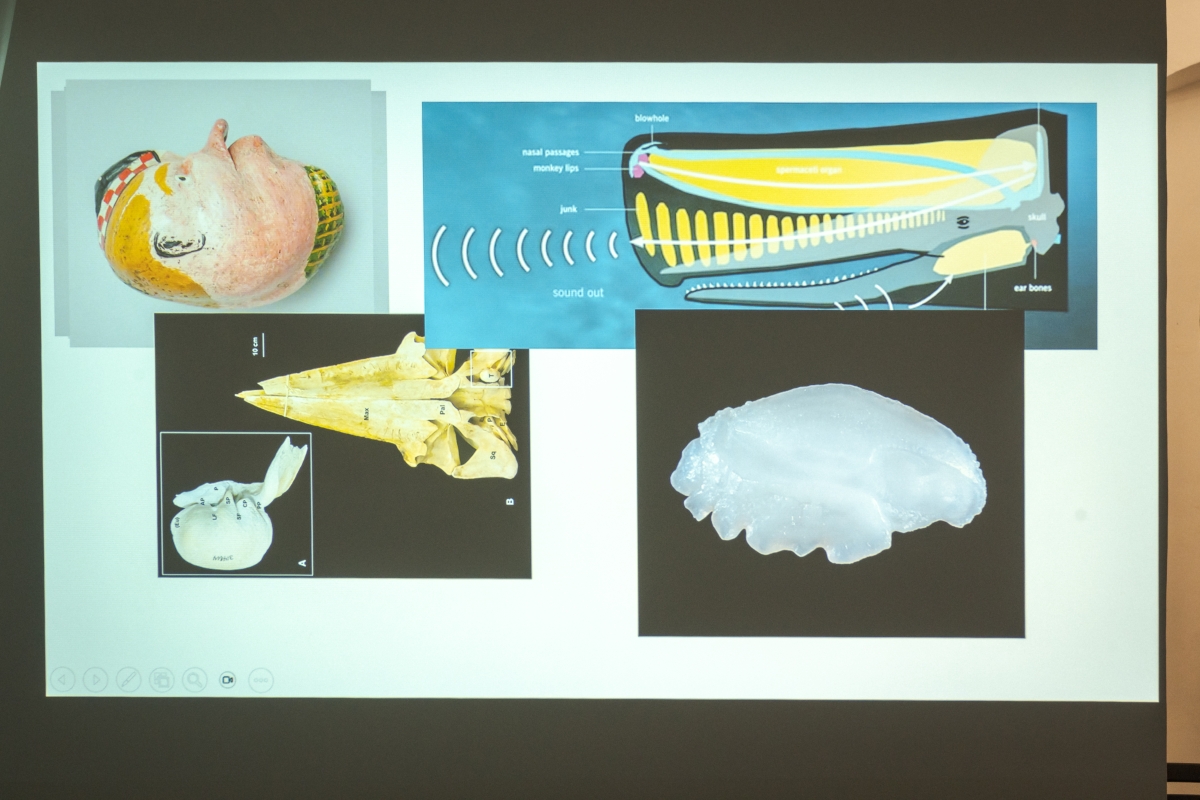

Whale ear bone (painted), Trinity House Maritime Collections, Leith, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Povilas Gumbis: Sorry that I had to stop you mid-sentence, but I had to be sure my phone’s recording this. You were saying?

Amy Watson: There are many interesting spaces in Vilnius. For example, there is a planetarium dome behind MO Museum. Framed by two trees, it reads as a sculpture. The projects one might realise in this space, given its intended function, might emphasise optical instruments and practices of looking, and how these have evolved. As well as the evolution of photography and cinema which at times runs parallel to that discourse. There is scope to work with ideas of the micro and the macro, of espionage and the military industrial complex. The next space I am visiting is the one you actually recommended when we first met.

Povilas: You mean the funeral home right next to the Olandai roundabout?

Povilas: It’s quite a building, they have twelve halls in which they can hold funerals concurrently.

Amy: An interesting project –12 memorials, working with artists to commission projects that respond to different deaths and rebirths; life and death, as we know, is on a spectrum.

Another modernist building that captivated me was the palace located next to the river Neris.

Povilas: The Palace of Culture and Sports?

Amy: Yes, I wanted to get closer to the building, but it’s been vandalised and there have been attempts to protect it, in other circumstances I would have entered to explore.

Povilas: Yeah, it’s been closed for almost 20 years now. Ever since then the place has been contested due to its tumultuous history. Recently, a commission of art historians, museum directors, heritage experts, and rabbis has been formed. Supposedly, a decision should be made by the end of the year.

Amy: What would you do with that space?

Povilas: I’m not sure. I think it has so much to it. For one, that whole area used to be a Jewish cemetery that was closed by Imperial Russia and later dismantled by the Soviet authorities. So in their preliminary discussions, the commission is trying to figure out how to pay respects to the now almost forgotten death of whole generations. Furthermore, the place hosted Sąjūdis (Reform Movement of Lithuania) meetings, the so-called ‘Rock marches’ that were integral to the Lithuanian emancipation from Soviet oppression. It’s also where the public funeral of the January 13th victims took place. So there are so many different histories to be accounted for if any future action is to take place. But, now that I think about it, maybe the word ‘different’ is the problem here – maybe these histories should be looked at as part of Lithuanian heritage without dividing them into issues pertaining to a specific ethnicity. But that’s easier said than done. From what I know, the commission is leaning towards a memorial museum.

Amy: In my experience, memorial museums are seldom living spaces. From what I’ve seen in South Africa, these kinds of projects initially receive funding from the state with an emphasis on infrastructure, and don’t make allowances for evolving exhibitions and programming. In turn, they become mausoleum-like, with exhibitions stagnating and beginning to embody a bereftness in a way that seems unproductive and unresponsive to new or alternative ways of looking back.

Povilas: Yeah, there has to be some active component of constant care for that history. A mausoleum could prove detrimental and almost an exact antithesis of what you’re trying to do.

Amy: These kinds of museums, especially when they’re about one singular history, don’t often evolve. I think the best time for creative practitioners to have access to a building is when it’s not sure about its future. The exhibition Between Walls and Windows: Architecture and Ideology, curated by Valerie Smith in 2012, considered how the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) in Berlin, an architectural landmark, might be experienced as a large-scale sculpture. In this exhibition the building was stripped of everything, access was made free and allowed through all entrances. Ten artists were commissioned to respond to the site and situation of the building, considering the concepts and questions which architecture attempts to answer as an instrument of history construction, philosophy and politics.

Povilas: Do you think it’s possible to combine all of the different parts of history into a single building?

Amy: I think working with artists there has scope to allow for contested interests and positionalities. Through a commissioning programme many truths can exist side by side. This isn’t propaganda. You can hold open spaces of memory, death, preservation, history, and heritage. Sometimes we only know by doing. I think there’s something to be said for practice to unfold in spaces like this in particular, precisely because they are contested and otherwise in a state of suspension. It is this status of the building as in a state of reckoning with its fractured past and its future uncertain, this state of becoming, that makes it particularly compelling as a site for artistic commissions and curatorial and architectural interventions.

Povilas: So I’m also getting the idea that even if a place has a local importance and is thus safeguarded by the locals from the outsiders, you would try and have international artists participate in this kind of project?

Amy: Having new perspectives on a context can lead to incredible insights and, in its best moments, be quite liberating.

Povilas: So being international is almost a necessity for the role of a curator – even if your practice is based in a very concrete location.

Amy: It can be dangerous to assume that only those who live in a particular location can offer any insight on it, and that in our current moment one’s context is somehow unaffected by international events. What I have found inspiring about inviting practitioners to South Africa is that they often see things anew, things that as locals we may have overlooked. A different perspective can reinvigorate practice and bring benefit to the programme for local practitioners and audiences. Placing work by local practitioners alongside practitioners working in other contexts actively demonstrates that we are all influenced by global events and discourses, and that many histories are shared histories. Rarely do things exist in a vacuum. Our histories and our futures are made in relation. Working with artists from one’s own context and those outside of it, or with some distance on this, challenges a tendency towards a parochial inward looking and an assumed exceptionalism.

1. Photograph by Andrej Vasilenko @ Articulations 3, Medūza, 30 August, 2023

Povilas: These ideas that we’ve been engaging with throughout the conversation – collaboration, space, international practice and influx of different relationships – all of it seems to coalesce into your current writing project the ear of the whale. Could you expand on that?

Amy: Several years ago I came across a pair of whale ear bones in a maritime museum in Durban, a port city on the east coast of South Africa. Each able to fit into the palm of a human hand, these objects were crudely painted with a human face, positioned as if looking at one another. In the COVID lockdowns I undertook research into these objects, and discovered what could be described as a folk tradition of whalers collecting these bones, which were retained as mementos or trophies of their life at sea. They were frequently decorated with paint and occasionally engraved. The tympanic bone, unique to whales, survives a whale’s death and decomposition because it’s the most dense part of the skeleton. Whales have sophisticated auditory capacities that enable them to communicate, navigate and locate themselves and others in space over vast distances, the tympanic bone is crucial in detecting and isolating sound. I consider the ear of the whale as a key or wayfinder for understanding relations between humans and more-than-humans.

Amy: (cont’d) In recognising our interconnectedness and interdependence in many ways, whales hold open the possibility of human survival. The whale is witness to and evidences our human histories of exploitation and global changes. Whaling powered the industrial revolution, and as Alexis Pauline Gumbs has pointed out, there are correlations between the transatlantic slave trade and commercial whaling. Whaling in South Africa is part of this wider history of extraction, colonialism and exploitation, which continues even today. And there are connections to this part of the world too. The whaling station in Durban was part of a colonial-era Scandinavian global whaling company. Recently evidence has surfaced that details how the Soviets whaled many species to the brink of extinction in secret, processing on average only 30 percent of the whale’s body, under the aegis of ‘leave a desert behind you’. The implications of how we conceive of the modern ocean and help recuperate it are profound for our own survival. I am currently writing about this research.

Povilas: Do you aim to expand the project beyond writing?

Amy: Yes, I’m interested in commissioning artists to respond to research, with those works having a relationship with the potentials and limits of our human sensory capacities. My intention is to have the project speak to locations and temporalities that are significant to whales. As a curator I’ve worked to draw on and foreground what artists are already undertaking research into in relation to what is most pressing in our world, as opposed to arriving at exhibition practice with my own ideas separate from artists’ practices. This opportunity is now to start with materials I’ve gathered and work with artists who are open and sensitive to it, a process that feels somewhat new to me.

Povilas: I see that you studied as an artist, so you do have experience of starting with your own ideas.

Amy: Yes, at one point I had wanted to be an artist.

Povilas: And how does this education translate in your practice?

Amy: I think having originally trained as an artist informs the ways in which I work. I have an understanding of materials and fabrication processes, and am able to troubleshoot and work through alternate spatial and material solutions. I recognise the vulnerability of what it means to put your work in front of a public and the learnings from doing so. I share artists’ research and forensic processes, as well as the highs of insight and practise-based learnings. At one point I understood curating as a sustained way of working collaboratively on realising something that is at times greater than the sum of its parts, and that curating, in its best moments, was a creative act that might illuminate shared discourse without reducing or instrumentalising practice.

Povilas: Was there no possibility to work with others as an artist?

Amy: Yes, there was, and I met the limits of collaborating in a context with little funding and support for visual art very quickly too. This has in part fuelled my interest in co-founding the organisation wherewithall with Chloë Reid and Kundai Moyo, which enables and supports the sharing of resources, interdependence and DIY exhibition making. Projects like wherewithall have the potential to radically change an arts ecosystem for a generation of practitioners in a city. It can be incredibly difficult to practise as an artist when working in contexts and under conditions that don’t support your work and can at times be unsustainable if you don’t practise in community. Having initially trained as an artist enables an understanding of the challenges of working as one, and I feel comfortable collaborating closely with artists, which I might not have done had I arrived at curating solely from a place of theory, exhibition histories and ‘instituent practice’.

Povilas Gumbis is an art historian interested in Eastern European and Baltic art of the 20th century, their post-soviet developments, resulting historiographies, and the contemporary scene. Presently he works at Rupert.