‘If we jump in with something that we think does not belong to us, we maybe have a chance to change something.’—Zoe Gudović

ACT 1

On the evening of Friday, October 20, in Vienna, the blue logo of the ‘bal’ conference gleams into the darkness of the street. It can be seen through the full glass front of Improper Walls art space, where the film screenings of artist Diāna Tamane and EYESORE members David Dawson and Nina Vukadin are about to start.

‘bal’ stands for the first three letters of two geographical regions of ‘Eastern Europe’: the Balkans and the Baltics. If an axis were drawn between them, it would span Europe from South to North, missing Vienna by only a few hundred kilometres. Justina Špeirokaitė, one of the conference’s curators, refers to them as ‘under-focused regions’ located at the ‘peripheries of Eastern Europe’ that share a history of Socialism and its ‘aftermath of turbulent political transition’. They run the danger, she stresses, of being homogenised under the label of Eastern Europe or isolated in the national contexts of post-socialist independence; the symposium will expose but not disentangle some of these regions’ (Špeirokaitė avoids the notion of countries) complex positions in the cultural fiction we refer to as Europe.

The conference is the result of the joined efforts of Improper Walls members Urtė Špeirokaitė, Julija Karimžanova, and Justina Špeirokaitė as well as art historian, curator and ETC magazine editor Hana Čeferin, art historian and organiser Merete Väin, artist Miloš Vučićević, artist Dejan Klement, dance artist and composer Bita Bell and art association ‘Die Labile Botschaft’. Vienna was chosen as a focal point where the artistically rich communities from both regions—though largely under- or mis-represented in the Austrian context—can meet and exchange. In a reparative reading, Vienna is reinterpreted as common ground for creating discourse and solidarity between them; a hijacked centre to exchange meanings from the periphery.

bal conference, Justina Špeirokaitė, Hana Čeferin. Photo: Urtė Špeirokaitė

The bal regions, a term invented by the curators, share the fact that their rich history of queer and feminist struggle and resistance has not made it into any official historical narratives, neither in the histories of the Socialist regimes, their nation-state successors, nor the Western-focused history of queer-feminism. Hence, the symposium gives the stage to these queer-feminist perspectives as an intersectional Other. The invited speakers, artists and performers are rooted in the geopolitical histories of the bal regions and/or in their lived experiences as people from the queer and FLINTA (female, lesbian, intersex, non-binary, trans and agender) communities. They uncover their genealogies in histories in which they have always persisted but remained unacknowledged, bringing their treasure troves of marginalised experience and knowledge to the table.

Diāna Tamane’s film Under the Same Sky starts. A voice begins narrating the life of an absent body, starting with her mother’s desire to nourish her well, her resulting overweight and her relatives’ conviction she would lose weight once unhappy love struck her for the first time. It quickly becomes evident this is the story of someone born into the cultural category ‘woman’. She recounts the beginning of her life in the Soviet Union, growing up in Latvia and studying in Moscow, while the images move through scenes of a contemporary life in a beach town. We follow a young woman engaged in her beauty routine, smartphone conversations and meetings with friends. These scenes linger too long to remain interesting but the dramaturgical talent of the speaker and the conceptual allure of the incongruent narration and image captivate the viewer. How does the depicted woman relate to the voice? Is she a stand-in, a re-enactment or an actress? Does the disparity between what is shown and told highlight a common denominator? Notions of femininity (i.e. how to be a woman) connect both protagonists but are never overtly addressed. Between the two, we gradually find out, lies a family generation and a move between East and West. Communist and capitalist societies are not presented as opposing entities; the voice gives no value judgement. Instead, the viewer begins to understand them as permeable and entangled both in the global market and the mundane rollercoaster of the speaker’s biography, who ended up settling in a Spanish tourist town due to a job listing recruiting young people from the Soviet Union to advertise Timeshare apartments. The film ends by bringing the ‘voice’ and the depicted woman together—they are mother and daughter—showing that the lives of individuals are always only party congruent with the dominant imagination of history.

Next up is the documentary KOLEKTИV: Intersections and Journeys across Belgrade by Nina Vukadin and David Dawson from the artist and urbanist collective EYESORE. After Tamane’s family-focused microhistorical project, this film takes the audience on an exploration of elective affinities in contemporary art and activism, following six artists, collectives, underground institutions and their communities. Their work focuses on the commons, carving out space for culture and solidarity in a city undergoing gentrification and supporting people on a local level. The artistic outcomes are portrayed as secondary to the relational processes of creating together or for an audience. EYESORE usually reflect on lived human experience in the structures of urban space; here they examine how their protagonists are socially intertwined with their surroundings and the significance of their locations in different parts of Belgrade. A member of one collective located on the outskirts of the city tells the interviewers ‘You have to want to come here to be with us’, reminding us that notions of centre and margin exist on various levels. In one memorable scene, visual artist Aleksandar Jevtić speaks of a society that takes care of ‘small line artists’, their small struggles and victories. When one of the interviewers asks for more information, he answers, ‘You are young, you are forgiven for not knowing.’, thus pointing to the value of local and alternative forms of knowledge, typically unheard in globalised discourses. EYESORE’s documentary allows the audience a glimpse into this place-based knowledge and we are left questioning: How much of the plethora of inspiring and socially engaged art do we usually miss out on because of the international focus of artistic winner culture?

ACT 2

The second day of the symposium is dedicated to panel discussions and performances. The discussion sessions tentatively assert a pattern that began to emerge during the film screenings: Baltic contributions (re)evaluate history while the Balkan (in this case ex-Yugoslavian) contributions stress present-day practices. The only exception is Sebastian Brank’s talk which analyses portrayals of the Eastern European intruder in horror films, thereby addressing the Western gaze (i.e. how the Eastern European identity has been represented antagonistically in Western cultural production). Still, this pattern of historical and present perspectives does not seem coincidental. Theorising the why requires a deeper look into how belonging to the Soviet Union and to Yugoslavia are framed very differently by contemporary evaluations and how these regions’ experiences of Socialism diverge. Especially in the cultural field, many people from the former Yugoslavia appreciate the past system of solidarity and stress the powerful sense of community among the member states. Zoe Gudović, one of bal’s contributors, spoke of the Yugoslavian communist system in a recent issue of Volksstimme, a left-wing Austrian politics and culture magazine. She said, ‘If one grows up in a system that supplies openness and connection to people […] and a politics of freedom and care, one gets a feeling of safety.’ In the Baltics, there seems to a be greater public consensus of the Soviet past as traumatic and nostalgia for Socialism is seen as increasingly problematic and as an imperialist taint in the face of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The talks do not only address the ruptures of political transformation but also genealogies and residues; for example, Rasa Navickaitė’s talk traces how the pathologised image of homosexuality developed in Soviet discourse seamlessly continued in the nation-state of Lithuania in the 1990s, still impacting public opinion today.

bal conference, Rasa Navickaitė, Sebastjan Brank. Photo: Urtė Špeirokaitė

bal conference, Justina Špeirokaitė, Piret Karro. Photo: Urtė Špeirokaitė

bal conference, Zoe Gudovič, Piret Karro. Photo: Urtė Špeirokaitė

This review, however, will focus on Zoe Gudović and Piret Karro’s talks, as they convincingly illustrate the necessity to fight queer-feminist battles with different dictions and audiences in mind. Although both claim visibility for FLINTA pioneers and are affiliated with academia, their approach to bal’s discussion format could not be more different.

Gudović start her talk by telling the organisers it was a risk to invite her as she is not interested in political correctness. Among many other practices on the art-activism continuum, she makes artistic interventions in public toilets to put art into the hands of those who do not think it belongs to them. If EYESORE’s documentary has positioned cultural work as an inherently social practice, Gudović brings to the symposium the questions: Is culture—with the audience it commonly interpellates (a term borrowed from Marxist theorist Louis Althusser who uses it to say that discourses always construct who their receivers are and which role they play)—enough to bring about social change? How can culture truly address those it leaves out? She is also a mediator who fights to bring marginalised cultural workers to the foreground. Her presentation stresses the erasure of lesbian artists from mainstream discourses, as well as from queer—understood as gay—discourses in the former Yugoslavia. Her forthcoming book is comprised of interviews with ex-Yoguslavian lesbian feminist artists. She rushes through her slides of artworks telling the audience, ‘There are so many, I just want you to at least hear their names once.’ Gudović speaks off-the-cuff, scrambles for words sometimes and addresses the audience in Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian when she doesn’t find the appropriate English expression. She punctuates her speech with her body, performing her presence against the very marginalisation she calls out.

Piret Karro’s words on the other hand sound as if they were chosen in advance. She has the refined clarity of somebody who has made her case repeatedly and her language fulfils the expectations of scholarly conduct. Her research is currently on show at the VABAMU Occupation Museum in Tallinn and she works as a government official for gender equality in Estonia. Karro has taken it upon herself to trace the history of the Estonian women’s movement. She comments on the hardships of even finding the concept ’women’s movement’ in historical data banks. How can you discover your ancestry when your name has been erased? Using the infinitesimally small fragments and faint clues she could glean from the country’s records that compile the part-truth of official history, she has pieced together a material cultural history in which Estonian feminists can root themselves.

This, she says, is a vitally necessary alternative to Western feminism, whose concepts and historical timelines cannot be neatly translated to or superimposed on post-socialist states. She stresses that in the Soviet Union, gender equality was proclaimed to be achieved with women’s access to paid labour, when in fact they were also deemed responsible for housework and childcare, and hence, faced a double burden. ‘A woman worked her first shift at the factory, her second shift at home and, if she was politically active, a third shift after that. In the Soviet Union in the 1960s, women were tractor drivers, while in the West they were housewives. Thus the third-wave feminist slogan “the personal is political” could only have been a mockery to Soviet women as their private life had been politicised in the name of the state long ago.’ Given these differences, Karro asks, ‘Can we even talk in the same terminology as Western feminists?’

As the audience asks questions, Karro and Gudović exchange looks that speak of hope, a kind of hope that results from being in the middle of something that seemed almost hopeless. Both work against the tides of hegemony which cast into oblivion present and past artists, activists and ancestors. With their different approach to language and action, alongside their different circles of influence, they dismantle the patriarchy from different sides with a common goal. Their presentations are acts of resistance against forgetting.

ACT 3

In a restaurant, an evening of performances takes place. One corner has been emptied of tables and a huge mirror covers the back wall almost entirely; it will mirror the performers and their audience. The night is dedicated to queer embodiment.

bENGA wRONG, a self-described contemporary pagan, enters the stage in tight leggings, stilettos, a steampunk-ish corset, a pink wig and a headdress made of Berlin rubbish, as they later reveal. Music plays in the background; the microphone is dressed in a bridal veil; a projection of cosmic light compliments bENGA’s Bowie-esque, space-age appearance. They orient themselves—‘Where am I?’—and claim their ground. There is little ambiguity in their self-confidence as they perform a rather conventional pop diva femininity. Then the music stops and a pristine robotic voice relays instructions. bENGA harmonises with it, repeating its question, ‘Are you a boy or a girl?’, first in confusion and then in almost-compulsive mockery. The voice speaks in riddles and bENGA tries to understand, ‘A sense? What is this? There is something more to get?’, thus equating existential questioning with profit. They simultaneously embody and make fun of neoliberalist identity search; their performance oscillates between struggle and self-promotion.

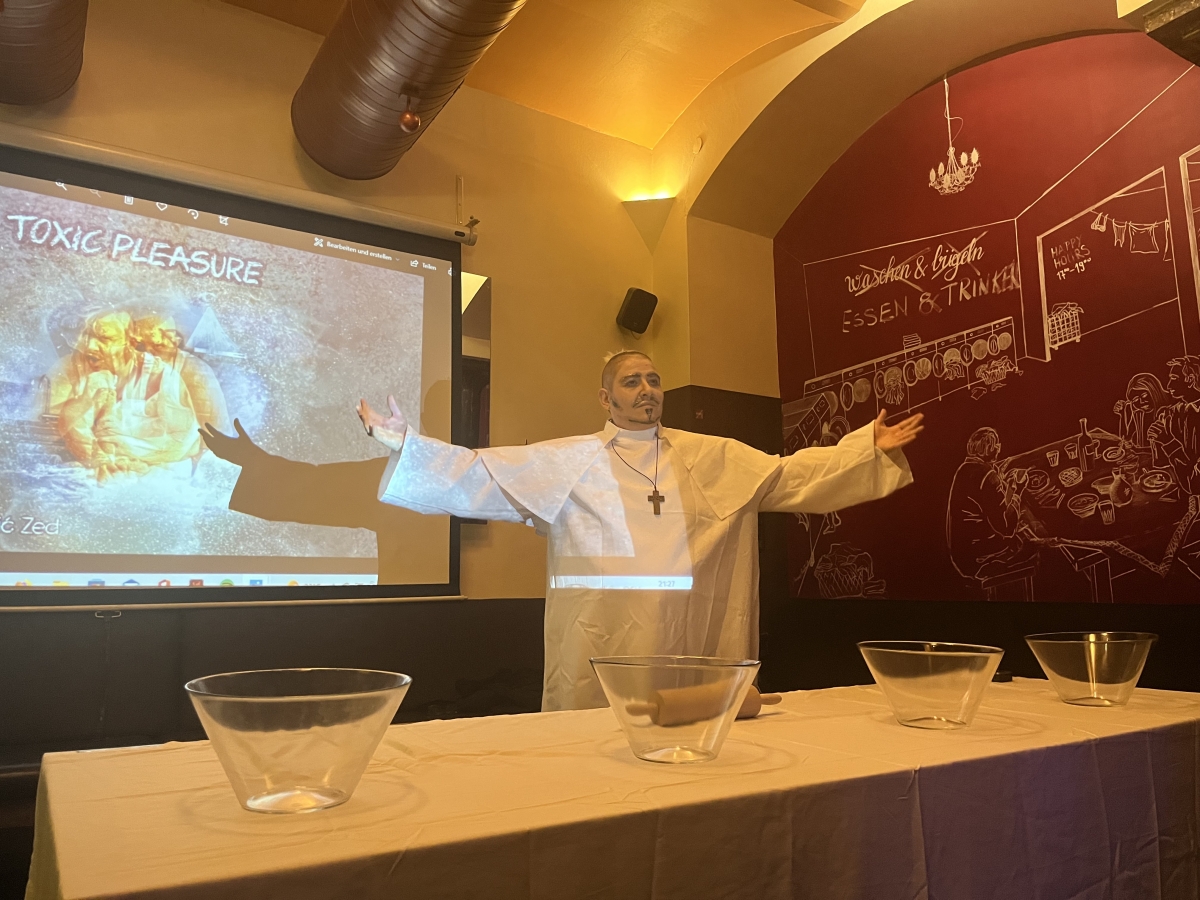

Zed Zedlic Zed—Zoe Gudović’s drag king alter ego—makes a rumbling entry, his voice fills the room as he introduces himself; the importance of his name reverberates like a battle cry. According to Gudović, this boundless confidence is something useful to be learned from men—for that reason, she facilitates drag king workshops for FLINTA people. Zed has prepared a PowerPoint presentation called ‘Toxic Pleasure’ and his message is simple: ‘Remember the power’. He points out the negative connotation of the word ‘black’ and takes off his black jacket to reveal a pristine white outfit he then complements with an apron that has a hypersexualised male body printed on it. He masturbates his rolling pin before changing into his white priest robe and handing out penis- shaped communion wafers. Viewers now hold a manifestation of power in their hands, one they can handle. The idea of ingesting it is unappetising; are we contaminating ourselves or appropriating something? Zed’s final words to us: ‘Now that you know what power looks like, deconstruct it.’

Next to the stage, Querelle, cultural worker Edvinas Grinkevičius’ drag persona, pushes for a queer eclectic glamour. Their costume combines elements of gay kink (biker hat), protest culture (balaclava) and punk (torn fishnet tights). His dressing gown is either latex or a bin bag. Inviting audience members to do one of his nails in exchange for a story, he talks about the struggles of organising queer events in Kaunas, of encounters with the police, the municipal government and the oppressive regime of Belarus, where their partner is from. In the second part of the performance, they hand out photographs of powerful, toxic male figures such as Benjamin Netanyahu, Donald Trump and others who have raised furore with their sexism and queerphobia. Using huge flesh-coloured dildos (hello power, we meet again so soon) they rip the pictures apart. Audre Lorde’s assertion that ‘the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’ comes to mind. Have the tools been transformed in Querelle’s manicured hands? How much do dildos themselves subvert the phallus? The line between subversion and perpetuation is a tightrope walk.

Last up is mirabella paidamwoyo dzurini. Vienna’s art/performance scene knows them for embodying queer and Black aesthetics and pointing to the tensions they create in hegemonial spaces. With the performer comes a sudden increase in the number of people of colour in a predominantly white audience. This prompts some of the symposium’s fundamental questions: Who is concerned by what is discussed here? Can different experiences of Otherness be negotiated together without losing track of each one’s specificity? The curatorial choice of dzurini’s performance can be interpreted as a closing of ranks with other intersectional Others, taking the symposium’s claim beyond the geopolitical bal regions for the first time. mirabella paidamwoyo dzurini presents a refined and simplified version of the performance vocabulary they have developed in the past years. They enter in a tight, skin-coloured suit with chains and straps, transparent plastic high heels and Frankenstein-esque blue-green face paint. With these accessories pointing to the history of slavery and the fetishisation of Black bodies, they radiate conventional feminine sexiness as well as unpredictable danger. Their voice is looped through a microphone as they begin to repeat sentences, invitations and intimate confessions such as ‘Come stay insane, it’s your favourite game’ and ‘ich liebe dich’ (‘I love you’ in German), until each one lingers in a net of contradicting interpretations. Do they express kinship? Are they threats or projected expectations? One phrase stays in mind particularly: “The part that hurt the most didn’t hurt enough’. Does it implicate an audience who feels comfortable enough in the status quo to rebel against it?

Reverberating in the skilfully executed and thought-provoking performances is a concern the symposium has left untouched: deconstructing femininity. Just as Tamane’s film never explicitly critiques the hardships of womanhood (beauty standards, care work and so on), the performances—except for Zed Zedlic Zed’s, whose critical use of masculinity becomes evident in context—employ sexualised femininity as a mode of expression through costuming and movement, but leave it unquestioned. This is in some sense the same, Western post-feminist debate that has been ongoing ever since Rosalind Gill coined the phrase ‘sexualisation of culture’. Can sexualised femininity be appropriated by queer-feminist discourse without dragging along the male gaze or a pressure-creating ideal? Making a case for this femininity through queer and feminist performance, reclaiming it from the derogatory patriarchal associations of being ‘superficial’ or ‘slutty’, has certainly been a coup d’état against gender hierarchies. But has it become so much a part of the queer repertoire that it can be considered hijacked and free of problematic meanings? What about other, more disconcerting images of a liberated FLINTA sexuality? Meanwhile, a few kilometres away, Kris Lemsalu’s portal-shaped sculpture Chará, reminiscent of a toothed vagina, smiles into the Viennese night.

A recap of bal conference can be found here: https://improperwalls.com/events/2023/10/20/bal-conference.

bENGA wRONG. Photo: Miloš Vučićević

mirabella paidamwoyo dziruni. Photo: Miloš Vučićević

Querelle. Photo: Miloš Vučićević

Zed Zeldich Zed. Photo: Miloš Vučićević

Zed Zeldich Zed. Photo: Miloš Vučićević

mirabella paidamwoyo dziruni, Querelle, bENGA wRONG, Zed Zeldich Zed. Photo: Miloš Vučićević

Zed Zeldich Zed. Photo: Miloš Vučićević