Aleknaičiai is a small village in the Pakruojis district, surrounded by rolling plains on one side and gently sloping riverbeds on the other. There are several homesteads, including a brick school built in the interwar period where a new quality and a rarely realized symbiosis of rural and modern culture meet, in Aleknaičiai Culture and Education Space (Akee). As Vilius Vaitiekūnas, the initiator and culture producer of Akee, said, it is difficult to specify when Akee started, but artistic and educational activities began to take shape there in 2018. The cultural centre is currently reshaping its goals and intentions, and aims to become a space for educational projects, artistic residencies and cultural projects, connected by the space of the former Aleknaičiai school and the community. In this interview, we talk with Vilius Vaitiekūnas, the inheritor of the building where the Akee space operates, about contemporary art emerging in the village, the uniqueness of rural areas, and Akee’s stories and ideas.

Vilius Vaitiekūnas. Photo: Lisa Jasperina Bommerson

Agnė Sadauskaitė: Vilius, before talking about Akee, I would like to get to know you as well. You are an art educator and artist, and studied for a long time abroad. In addition to your activities in Aleknaičiai, you have also worked at the Contemporary Art Centre in Vilnius. Tell us what activities you are currently focused on.

Vilius Vaitiekūnas: I am now focused on my studies in Helsinki, studying the MA programme in Visual Cultures, Curating and Contemporary Art at Aalto University. As I am almost halfway through my second year, I have been putting together the outline of my thesis with my supervisor for the last few weeks. Before that, I worked at the Centre for Contemporary Art as a curator of education and community engagement, and I studied in the Netherlands at Minerva Academy and at the University of Groningen. The knowledge I gained about discourses in art, cultural sociology and cognitive sciences shaped my view of contemporary art and culture in general.

I am also nearing the end of my post-academic studies initiated by the Spain originated Inland collective – Inland Academy. Together with other participants in the programme at the Academy, we delve into so-called folk knowledge, the cultural distinctiveness of rural areas. We visit different initiatives, exhibitions and events in Europe that are engaging with and operating in rural areas. In the Inland Academy programme, we pay a lot of attention to the analysis of today’s power structures, the dynamics between the countryside and the city, the reflection of the culture that exists and that can take place in the countryside, and the traditional contemporary art. In addition to academic activities, I also initiate cultural education workshops, cooperate with different organisations, and contribute to the establishment of cooperation networks. I am trying to understand what kind of world we are inheriting and creating. So now I spend time positioning myself and doing various experiments. One of them is Akee.

AS: What made you interested in combining traditional culture and contemporary art?

VV: Before answering this question, I will clarify that it is not so much the connection that is important to me, but creation itself in the countryside, and its impact on the cultural field in general. Rural areas have their own cultural, historical and social tensions, and due to them and the ever-increasing need for resources, they are rapidly changing. The countryside 15 years ago and before is very different to what it is today. Swift urbanization, the impact of entrepreneurship programmes, and investment (and expectations) by large companies are changing the countryside, the biodiversity, and the communities and their needs. Meanwhile, contemporary culture, be it contemporary art, dance, architecture or other forms, at least in my experience, is often created and matured while experiencing urban spaces and echoing questions, sensations and changes that are important to these spaces. Of course, it’s not that the countryside and the city are like two separate poles, they depend on each other, but they also have differences, which, it seems to me, pose a certain burden for the people who create in them. It is also a question of perspective, from where certain problems and tensions are viewed. After all, experiencing global warming and thinking about it in a city, university or gallery is different to taking care of bees in the countryside and seeing how their population changes due to the unstable weather conditions, farming methods, etc. I say this and I think of my grandfather, who has lived in the countryside all his life. He started keeping bees almost a decade ago, and his observations about changing nature shook me more than statistics about the decline of the bee population that I have read in any book.

Now it seems that I have become interested in the countryside by chance, because the former Aleknaičiai elementary school was partly inherited by my family. However, looking deeper, as far as I know, most of my family come from the countryside, and only my parents’ generation has had the opportunity to build a life in the city. So by being interested in the countryside, I continue developing a relationship both with my family’s past and with myself. I rarely talk about it, therefore I don’t have a particular vocabulary to articulate it, but I feel the continuity and responsibility. After getting familiar with research on culture and sociology, different ways of creating and obtaining knowledge, and how public discourse is being shaped, the rural areas in the Baltic region appear as a little-researched field. Or at least I haven’t found that would resonate with my own interests. In addition, the city is cramped, and, at least how it appears to me, many participants in the cultural field are overworked, which, I believe, also affects topics and ways of speaking that are important to us. So maybe by creating such a space in the countryside, we will come up with some solutions for tensely furrowed brows and stomach aches. And, of course, we will expand the infrastructure of the cultural field, and find new and effective ways to share things that are interesting to us.

Akee surroundings, 2021. Photo: Alexandra Bondarev

Akee surroundings, 2021. Photo: Alexandra Bondarev

AS: During our email conversation, you mentioned that the intention to create Akee was as important and changing as the cultural space itself. It would be interesting to know what the main impetus behind the creation of Akee was. How did the idea come about? In addition, what are the main motives now that four years have passed since the beginning of the foundation?

VV: It is difficult to point out the date when activities started here; perhaps we can think of Akee’s activities as an inheritance and adaptation to what came before. My own initiatives here began when my grandfather Vytautas inherited part of the Aleknaičiai Primary School building and the nearby land in 2014 from the teachers Stasys and Bronė Grušas who lived there. In the summer of 2018, I returned to Lithuania from my studies in the Netherlands and wanted to explore the property of my family and spend time with friends in the countryside, so I came here with several artists. We found everything as it was: scents, clothes, stationery, school records, documentation, and other things. At that time, I didn’t think much about what we were doing here, we just started organizing the former school, sorting out and archiving the material we found.

I also told the journalist Juta Liutkevičiūtė on the radio programme Ryto Allegro that in August 2020, when I returned to Lithuania and worked with the Artscape Arts Agency, its director Aistė Ulubey and her colleague Ieva Šlechtavičiūtė suggested establishing an association, writing an international project together, and creating an infrastructure for cultural activities. We had about forty days to buy the rest of the property, come up with the concept, write the application, etc. We made it on time, with the help of residents of the Pakruojis district and others. Unfortunately, although we were very close, we did not make it into the top five and missed the opportunity to get a decent amount of money to repair the property. Looking back at that marathon now, it seems good that it all ended like that: Artscape has spent the last two years on cultural education activities for refugees and their representation, development of a socially engaged art discourse in the Baltic countries, while the last few years have allowed me to think more slowly about what I would like to do with the inherited school building.

AS: The Akee space is in the former Aleknaičiai village school, which functioned from 1939 to 2000. This space, full of stories, is brought to life by your own hands, and the school archive is being prepared. Does the historically rich space influence the direction of activity?

VV: Oh yes, it does. There is a sense of continuity and meaning when looking at the history of the school. It was built with local people’s money before the Second World War with the intention to create a space where the children of the community could develop. So it was a future-oriented space, and we want to keep it that way.

Akee interior, 2021. Photo: Gabrielė Žukauskaitė

Akee interior, 2021. Photo: Gabrielė Žukauskaitė

Akee interior, 2021. Photo: Gabrielė Žukauskaitė

AS: When it comes to people’s experience, the community aspect also naturally emerges, especially since one of Akee’s goals is to increase accessibility to culture in rural areas. What is community engagement? What do you think this space can offer to the village of Aleknaičiai and the surrounding settlements?

VV: Yes, this broad and dry statement is in Akee’s future goals, but we don’t have a refined strategy for its implementation. And honestly, I don’t think that committing to create and execute one is really where I would see value for this project at its current state. As of now, the goal is to devote our energy to experiments, which are primarily about finding ways to work with and bringing the rural context into the discourse of contemporary culture. In order to share what we uncover or learn while being here, we create and develop educational programmes. Of course, the projects we carry out are related to the context we are in, but as it seems now, it is not so easy to involve a person who is not interested in a so-called contemporary professional culture, when he/she/they do not have a personal connection with its creators. Therefore, we are trying to create this connection. Since we have been running projects for three years now, we purposely aim to cooperate with local institutions, to get to know members of the local community, people working at local schools, libraries, and local authorities, because only by working together with them is it possible to increase accessibility to culture. By meeting locals, one also learns a lot about the place itself. Many inhabitants of this region have a connection with the Aleknaičiai school as it was active for more than 60 years: they studied, worked and sent their children to study here. People are curious, and we’re looking for the best ways to communicate with them.

AS: It seems that the most extensive activities take place when you return to Aleknaičai. Does the centre have ongoing activities?

VV: The space is crowded during the summer, there are always artists staying here, residencies and educational activities happening, visitors come, my grandfather is beekeeping here. However, there is no continuous programme, and at least there won’t be while I’m in Finland.

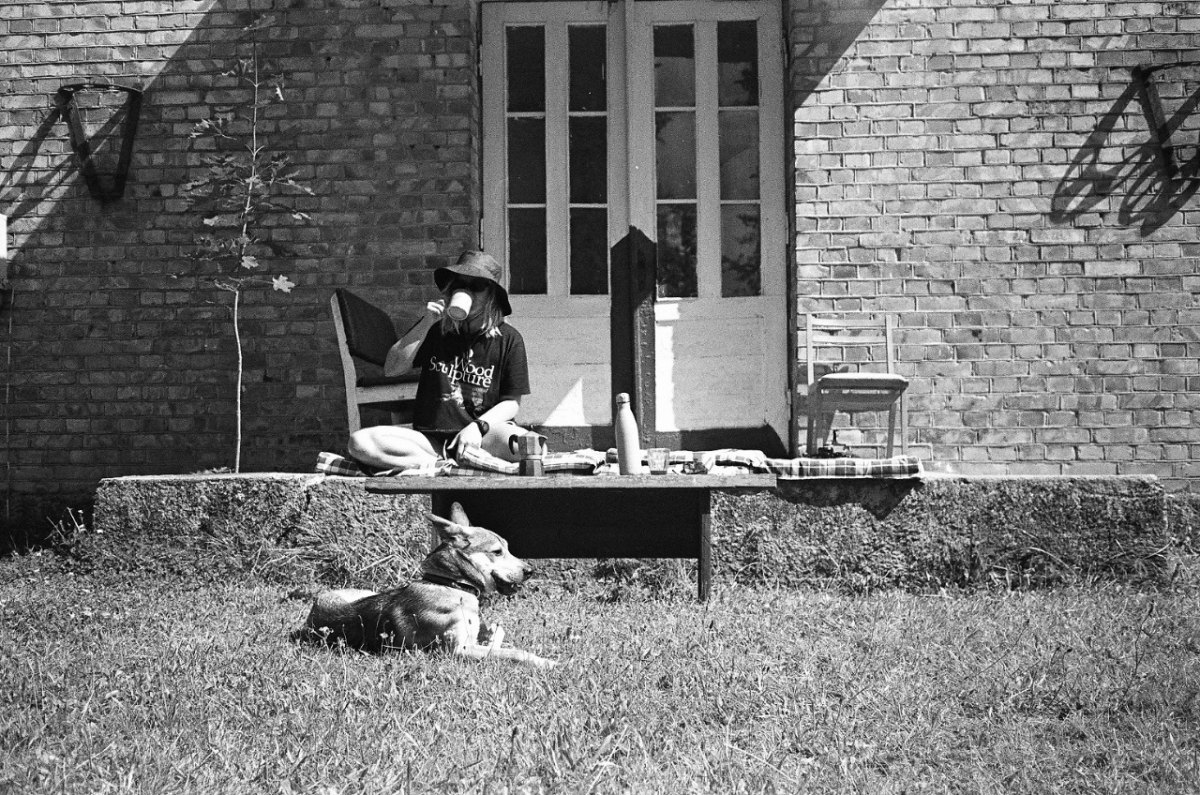

Photo: Aleksandra Bondarev

Akee interior (Bon Alog and Simba). Photo: Aleksandra Bondarev

AS: You mentioned that Akee’s activities were greatly influenced by your participation in studies at the Inland Academy. Combining rural and contemporary art culture, academic and rural knowledge, this learning space focuses on the search for new forms and interdisciplinarity as a response to the ongoing climate crisis. What experiences and knowledge gained at the Academy contributed to the formation process of Akee?

VV: That is very true. In particular, the example of Inland is encouraging. For more than a decade, they have been carrying out various cultural activities related to rural areas while often using tools to engage with the local contexts that are typically associated with contemporary culture. Further, they also create a real impact on the European cultural field. Participating in the Academy made it possible to comprehend the similarities between and experience problems of cultural institutions in the countryside and in the contemporary art field. This was very important in contextualizing and trying to understand in what context Akee is, and what problems we share with other institutions. Also, I found many like-minded people, and my vocabulary for articulating specificities of culture in the countryside has improved. Inland Academy puts lots of effort in identifying how and to what extent the contemporary art field has participated in the formation of rural areas and culture, how those participants in the field spend time or perceive rural areas, and how those areas are affected by global processes.

AS: So, in addition to many aspects, the Inland Academy helps to verbalize the processes taking place in rural areas.

VV: Indeed. Institutions that take a critical look at rural areas in different parts of the world are now being established and are successfully operating. The emerging infrastructure for their collaboration is beginning to shape the way we speak. Sociological, cultural, geological, ecological and other research is carried out nearby, allowing the problems and existing resources in non-urban areas to be identified, and people coming from the contemporary art field can apply their knowledge here.

AS: What is the main mission and aspiration of Akee? Perhaps it is as changeable as the intention behind creating the space.

VV: It is difficult to talk about it: the intention changes with time and so does the mission, especially before I have assembled a team that will bring its own insights. I see Akee as a community-building project. I would like to expand the infrastructure of contemporary culture to the regions, and create a non-urban perspective for seeing the world we inhabit. For me personally, Aleknaičiai is a space through which I now think, shape my scientific research, and instrumentalise it in this way. There are a lot of social and cultural issues that one may want to look at, but this can be done only after accumulating knowledge, finding partners, learning from them and applying what they have learned through their activity..

Project ‘Lokal radio’. Photo: Vilius Vaitiekūnas

Project ‘Lokal radio’. Photo: Vilius Vaitiekūnas

Project ‘Lokal radio’. Photo: Vilius Vaitiekūnas

AS: It’s great to see that the basis of Akee is already in place, but the space itself is still being shaped and changed. This gives an impetus for a new space where not every detail or aspect of the activity is documented but changing.

VV: I do this deliberately as I don’t find constructing an image through a declared future impact first, and then chase this image through organizing different activities. Now we have an abandoned school building, we have carried out some projects and this is what Akee is. It seems to me that this is one of the advantages of non-governmental organizations: they can be flexible and adjust their trajectories while their team is changing. Also, this state of uncertainty makes the space much more receptive to the events that the present brings, allowing for a more operative response in the unforeseen future. For example, I was very interested in the Millennium Schools project (Tūkstantmečio mokyklų projektas in Lithuanian). I am thinking about how it could be helpful in expanding the infrastructure of the Lithuanian cultural field to the countryside.

AS: Do you accept the idea of eroticizing the countryside, of making it a recreational area?

VV: Exoticization in itself can of course be, and often is, problematic; but if it is so, then I am more interested in thinking about why and how it appears instead of accepting or rejecting it. Now, speaking from a position of a ‘justice warrior’, it may not seem to be very ethical to reduce the countryside to a place that only nurtures ‘traditional culture’, serves as a break from the city and its pace of living and where one can experience the ‘wild’ nature. However, inhabitants of the countryside themselves often use these images when promoting rural tourism, local products and more. I don’t have a better solution on how to see the countryside, but I myself try to look at it as comprehensively as possible.

Kamilė Krasauskaitė at the residency. Photo: Aleksandra Bondarev

AS: You have been running art residencies at Akee since 2018. Tell us more about them.

VV: As we have a beautiful building, and it doesn’t cost too much to maintain it in the summer, we try to keep it as open as possible to anyone who wants to come. So far, Akee’s residencies are not in a fixed format, as they are held differently every year. In the first year, it was a group of friends who wanted to explore an abandoned building together. Later, we started writing project proposals for the Lithuanian Cultural Council (Lietuvos kultūros taryba in Lithuanian) to execute specific artists’ projects. Eventually, artists themselves started contacting us, and asked if they could come and hang out. I think we will continue this way further on.

AS: Are you planning to write a residency project for the coming year?

VV: Yes.

Workshop for kids by Kamilė Krasauskaitė, 2022

Project ‘Lokal radio’. Photo: Vilius Vaitiekūnas

Project ‘Lokal radio’. Photo: Vilius Vaitiekūnas

AS: Many (cultural) activities and events in Lithuania, as is often the case abroad, are concentrated in big cities, while the Aleknaičiai community operates in the countryside. What challenges do you face when developing an educational space and artists’ residency far from the centre? And at the same time, what benefits and surprises does it bring?

VV: I am not at Aleknaičiai all the time, and the space itself, at least until now, was created quite intuitively and not very strategically, so the challenges arise primarily from this way of working. If I were to spend more time here, I think the first challenge would be the geographical distance and the not-very-convenient public transport from Vilnius and Kaunas. The majority of professionals in the culture field live in those cities, so participating in the cultural discourse and shaping it while being 200 kilometers away from cultural centers has its advantages and challenges. It is welcoming that funding and opportunities are increasing for cultural producers to operate in the countryside, but most of us operate specifically in Vilnius and Kaunas. Another problem, as for many non-governmental organizations, is funding. Most of Lithuania’s cultural budget is allocated for the maintenance of property and state institutions, so in order to create a space like Akee, it is necessary to apply to various funding structures, which often impose compromises.

When it comes to advantages and surprises, while staying in the countryside, one can observe natural processes, food and resource extraction industries more clearly, and experience the sense of continuity if one’s own ancestors come from the area as such. Allowing more space in the countryside can develop a perspective that, at least to me, appears as important in the future. Further, rural communities, local institutions and businesses in Pakruojis district are open to newcomers, and help new initiatives to settle, local educational institutions integrate our events and educational programs into their activities with excitement. It is also a joy to notice that my friends who work in the cultural field are also willingly involved in the development of Akee, so it becomes a joint project.

AS: What are Akee’s plans for the future? Do you plan to expand the range of activities?

VV: As of now, it doesn’t feel right to speak about things that haven’t been done yet, thus it would be rewarding to create more opportunities for discussing topics related to the countryside, the heritage, the extraction of materials and their use within the discourse of Lithuanian culture in the coming years. Also, it would be great to invite more friends and colleagues to develop their practices and research here, in the countryside, involve more students in high-quality cultural educational activities. The future will tell, maybe there will be public lectures, reading groups, inter-institutional collaborations, or maybe just a rewarding honey harvest and opportunities to spend time by the lake in the summer.

Akee interior, 2021. Photo: Gabrielė Žukauskaitė

Akee interior, 2021. Photo: Gabrielė Žukauskaitė

Akee logo