An interview with Corina Apostol, the curator of the exhibition ‘Orchidelirium: An Appetite for Abundance’, representing Estonia at the 59th Venice Biennale in 2022, together with the artists Bita Razavi and Kristina Norman (23 April to 27 November 2022).

Placing historical and new artworks side by side, the artistic team proposed a multifaceted view of colonial history and the critical issues that surround it. ‘Orchidelirium: An Appetite for Abundance’ was inspired by the watercolours and paintings from the first decades of the 20th century by Emilie Rosaly Saal (1871–1954), a forgotten female artist from Estonia. Saal’s works, some 300 images of tropical flowers, fruit and vegetables, depict plants from different corners of the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia, then part of the Dutch Empire), where she lived and travelled with her husband Andres Saal between 1899 and 1920.

The new works by Kristina Norman, Bita Razavi and Eko Supriyanto, based on Saal’s legacy, give a new perspective with various new elements and a unique story that challenges questions of colonialism, gender representation and botanical perspectives towards both femininity and belonging. The project reflects the difficulties of entangled histories and the relationships between ‘perpetrators’ and ‘victims’.

Artistic team together with the commissioner Maria Arusoo. Photo by Denes Farkas/CCA Estonia.

Alexia Menikou: Corina, can you tell us a bit about your curatorial practice in general?

Corina Apostol: If I were to describe what I do in three words, it would be: curiosity, caring and constructing. I am trained as both a curator and an art historian, and I have a passion for uncovering hidden or erased microhistories that give us clear insights into the bigger picture of our times, who we are, and our heritage. In my approach to my projects, I cultivate empathy and personal connection to the subject matter, especially around difficult topics. As someone who grew up in communist Eastern Europe, more exactly Romania, and matured and studied in both the new East and the West, I am constantly building connections between contexts and between cultural practitioners from different fields.

The word ‘curator’ comes from the Latin cura, which refers to care, or cure. But the word has a long history that stretches back to the Germanic/Old English chara/caru, meaning ‘grief, sorrow and trouble’ and the Old Norse kör, for sickbed. Having worked both in art institutions and public spaces in Europe and the USA, I have chosen my projects to represent my concern for and personal interest in some of the most crucial issues of our times. I enjoy working closely with artists to present art exhibitions, projects and experiences to a wide audience who may or may not be familiar with art history. Every great project starts with a deep connection between people to engage in a subject that can be equally one of concern, caring and anxiety about a topic, and at the same time a question of empathy and wonder towards the subject matter.

AM: What do you hope visitors took away from ‘Orchidelirium. An Appetite for Abundance’?

CA: The story of Emilie Rosalie Saal, an artist I began researching together with the artist Kristina Norman, is exceptional, and it is a story that is not well known, not even in Estonia. I wanted to make a connection between her practice as an artist who was acclaimed in the USA for her botanical works, Estonia’s role in colonialism in Dutch Southeast Asia, and patriarchal structures and her own emancipation at the expense of her female servants. I am proud that we were able to bring this story to the Biennale and show it in the Dutch Pavilion, using the context and the structure of the building itself as a background to the exhibition. I hope the visitor’s curiosity will encounter the imagination of the artists and my research, which dramatises Emilie’s story, making unexpected connections between contexts, histories, peoples from the past and the present, humans and plants. I am glad to hear that we had had tens of thousands of visitors to our pavilion, and the feedback was overwhelmingly enthusiastic. The topic we chose for the exhibition is not an easy one, and the process has been one of learning about others’ experiences of colonialism, and the re-evaluation of our own cultural heritage and assumptions about our histories; therefore, I am pleased that the message of ‘Orchidelirium’ has touched many.

Kristina Norman. Photo from the set of film trilogy Orchidelirium, 2022 (digital video with sound, total running time 35 min) Photography Erik Norkroos. Courtesy of the artist.

AM: Can you give us an overview of the central themes explored in the exhibition?

AC: Desire, seduction, the choices we make and their consequences, how we treat others when we gain power, the essence of human knowledge about nature, and the endurance of colonial structures, to name a few. Emilie and her famous 300 paintings of plants from Indonesia, especially her collection of 100 rare orchids, serve as a case study to access the world of 19th-century colonial empires and the experience of colonised peoples, and to draw out the ramifications of buried truths to our present moment. For example, in the film Thirst from the Orchidelirium trilogy, Kristina Norman weaves a dystopian magical universe, where machines mass-produce and transport peat from Estonia to nurseries in the Netherlands, where orchids, whose ancestors were once harvested from colonies, are bred and then transported back to be sold in Estonia and beyond. From the very beginning of the project, I wanted to give a space to our peers, curators, artists and researchers from Indonesia, to give their own accounts of these histories. I invited the curator Sadiah Boonstra and the dancer Eko Supriyanto to develop Anggrek (Orchid), a performance film that, at intervals, interrupts Norman’s film trilogy and engages in a dialogue with our insights into Emilie’s story. Recorded in Java in Indonesia, the piece explores the colonisation of indigenous nature, highlighting the continuing exploitation happening in Indonesia. The film invites the viewer to remove the bars of the colonial gaze with its exoticising cover that disassociates these flowers from their indigenous lands.

AM: What was the design process of the exhibition? With so many strands to the exhibition, was it a complicated one?

AC: I am glad you asked this question, because reviews usually focus on the works of art and the concept of the exhibition; however, in our case the design of the exhibition was integral to the message and the experience we wanted to create. We worked with a talented team of architects, Aet Ader and Arvi Andersen from b210, and I also asked my gifted colleague Kristaps Ancans to help shape the space based on the ideas of the artistic team. Kristina Norman had the original idea not to use the main entrance of the pavilion, but to have the audience enter from a side entrance. She based her idea on her research into the verandas of Estonian manor houses, which were spaces for the privileged and were closed to servants. At the same time, Bita Razavi suggested dividing the audience entering the space to create slightly different experiences, both from the point of view of physical experience and visual information. I really loved the synergy between the two artists’ ideas, and we decided to develop it together.

Inside the space, I worked closely with Aet, Arvi and Kristaps to solve the challenge of placing the films, sounds and spatial installations by the artists in a venue that was built to showcase modern art, such as painting, sculpture and photography. Kristaps described a very beautiful solution of rounding the square corners of the space, which would solve the sound question and transform the space into a flower that opens its petals, as seen from above. He also designed the ‘Wardian cases’ (based on historical cases that were used to transport plants from indigenous lands to European markets). I came across these cases that formed the foundations of empire-building through the commodification of nature in my research, which I shared with the artists, who were both keen on including them in the physical space. Instead of plants, we used them to present a selection of archival research together with a poetic commentary that I wrote. I debated with Kristaps what to select over the hundreds of photographs and texts, and chose a handful that corresponded to different themes: womanhood, motherhood and emancipation, ambition and power, independence and imprisonment.

We also engaged a very gifted designer, Laura Pappa, who conceived an amazing botanical font based on the concept of the show, which we then used in our signage and all communication, including a gorgeous set of postcards based on archival research and the artists’ new works, which have turned out to be very popular with visitors.

Gardener packing plants inside Wardian cases at the Buitenzorg Botanical Garden Kebun Raya Bogor, 1913. Courtesy of the Tropenmuseum Collection Amsterdam.

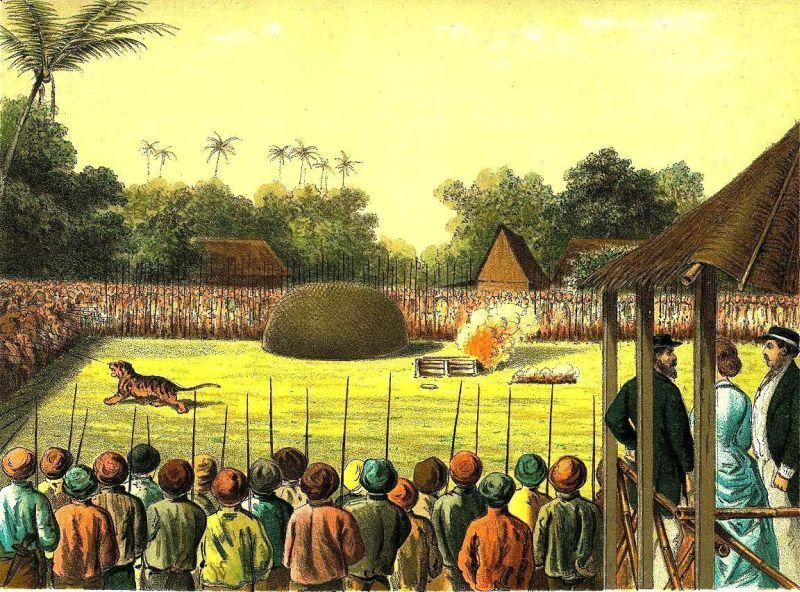

Josias Cornelis Rappard, Tiger Fight on Java (c. 1883 – 1889), lithograph, courtesy of the Tropenmuseum Collection, Amsterdam.

AM: How did you come across Emilie Saal’s work? If you had the opportunity to interview her now, in the present, what would you ask, and likewise, if you could travel back in time?

CA: Long before we even found out about the open call for the Estonian Pavilion in Venice, I wanted to create an exhibition with Kristina Norman giving a fresh perspective on colonialism, demonstrating the Estonian people’s own ambitions to colonise or be in the position of powerful figures in colonial structures. One of our case studies was the story of Emilie’s spouse, the writer, cartographer, photographer and traveller Andres Saal. He is known locally for his novels on the struggle by Estonia to become independent from the Russian Empire, as well as for being a high-ranking official in Dutch Indonesia, working directly with the Dutch colonial army. We learned about Emilie in the footnotes to her husband’s biography. I was intrigued by a passing mention of her exhibition of over 300 paintings at the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science and Art in 1926.

I immediately started searching for her works, and even though my initial inquiries at museums, galleries, collections and archives didn’t turn up any of her original works, I was able to find lithographic copies of them on online trading sites. The people selling them had no idea who Emilie was or the significance of her practice, they were simply looking for buyers who wanted to decorate their homes with her work. I began ‘hunting’ for more copies, and managed to collect about thirty for my archive. In a way, this inspired the title of the exhibition ‘Orchidelirium’ or ‘orchid madness’, referring to the period in 19th-century Europe when wealthy merchants, kings and collectors deployed orchid hunters to go to ‘exotic’ places and pillage the indigenous landscape in search of rare specimens.

Bita Razavi Kratt, 2022, kinetic sculpture. Photo: Anu Vahtra.

AM: How did you meet Kristina Norman and Bita Razavi? How did the collaboration for Orchidelirium form?

CA: I was already familiar with Kristina’s work before I started working at the Tallinn Art Hall in 2019. She is one of the most gifted artists and filmmakers in the Baltic, often dealing with difficult topics around the experience of people in a vulnerable position in society, and I asked her to collaborate on an exhibition. We applied together in the first round of the competition for the Estonian Pavilion with the ‘Orchidelirium’ project proposal, based on a previous idea we had planned for an exhibition at the Art Hall. We both believed it was an amazing fit, as our idea revolved around colonial relations between the Netherlands, Estonia and Indonesia through a botanical lens, and we had the opportunity to present our work in the Dutch Rietveld Pavilion in the Giardini!

After the jury suggested we expand the artistic team, we turned to Bita Razavi, to whom we introduced the ethical aims of our project (the most important of which was the representation of the Indonesian point of view or voice in the project), and she agreed to contribute work to ‘Orchidelirium’. From then on, the project developed as a collaboration between us, and each of us had the creative freedom to invite our own creative partners and advisors to support us in this multi-layered project.

AM: While a positive gesture from the Netherlands and the Mondriaan Fund to invite Estonia to use their Rietveld Pavilion in the Giardini for the Biennale Arte 2022, the fact remains that it is mainly only the ‘older’ and ‘richer’ countries in Europe that have permanent pavilions in Venice. Does this correspond with the power struggles explored in the exhibition in the Estonian pavilion?

CA: It is true that this gesture of handing over the pavilion, or pavilions exchanging locations, is rare, but it has happened in the past. Historically, Estonia is not allowed to have a permanent presence in the Giardini. The Biennale itself is still built around the antiquated notion of nationality and the national ethos, which doesn’t correspond to the reality in the art world today, where identities are more fluid and more complex. Nonetheless, we decided to use this opportunity to challenge the notion of national representation today, and the colonial power structures that underpin it in the European context. Firstly, the topic of the exhibition as I described it engages directly with national belonging and emancipation. Secondly, the composition of the team itself breaks through the constraints of nationality. I am a Romanian living in the Baltic for the past three years. Kristina is Russian-Estonian. Bita is originally from Iran, and lives between Estonia and Finland. And our guest artist Eko Supriyanto is from Java in Indonesia. I hope that in the future the Biennale will update its structure and allow countries that have been subjected to colonial rule to have a more prominent space in the Giardini, as well as encouraging exchanges that may lead to exciting connections between contexts.

AM: Did the pandemic delay to the 59th Biennale Arte affect or alter the exhibition in any way?

CA: Of course we had to adapt to the challenges of not being able to travel or connect with each other in person. But at the same time, that extra year of work on the Estonian pavilion gave me the necessary time to deepen my research in Europe and the USA, and read more books on the topic of botanical colonialism. Also, Kristina Norman used the time to really develop her film trilogy, research locations in Estonia and the Netherlands for shooting, and collaborate with experts in manor houses, local business owners and historians. And although we were never able to reach Indonesia due to the travel restrictions, we were able to connect with our collaborators Eko and Sadiah by Zoom meetings, and exchange research and ideas over the course of several months. I am very grateful to Eko for developing the film Anggrek along with our story. I believe he found an amazing way in collaboration with Putri Novalita to shake off the hierarchies and oppressive elements that stem from colonialism in nature, even in postcolonial conditions.

Emilie Saal in collaboration with Andres Saal, Tropical fruit still-life, overpainted photograph, c. 1910-1920. Courtesy of the Estonian Literature Museum.

AM: What is the role of art in times of unrest and suffering, and what is the role of the international exhibition at the Biennale Arte during such global crises?

CA: Art is not a magic pill or a ballistic weapon. Empathy is not developed by just looking at a piece of art: it involves work on the part of the viewer as well, work for which art gives us the materials, the aesthetic, intellectual and emotional tools. Art cannot solve the climate crisis, end colonialism, or cure a pandemic. It cannot win elections or overthrow a government. It cannot undo the massive harm millions of people on this planet have suffered because of war. We cannot bring the dead back to life. Nevertheless, it is a form of resistance, repair and knowledge, creating new understandings, new languages and new ways of being. The best things are usually delicate, and the fact that they are not obviously useful or efficient is not an argument against the value of art, but an argument in favour of making sure that art and its makers can continue to survive.

International art exhibitions are a tool to bring together different propositions for the world as it is and how it could be. It is a slow tool, which doesn’t act immediately, although it may provoke a reaction from the public or the media straightaway. I have approached my international exhibitions by experimenting, analysing, looking at thought patterns, and at what forms art can take in context. There is a degree of surprise when working with artists to construct an exhibition. Without that, there is no risk, no adventure, and no discovery. Although I have focused on socio-political topics in my shows, I believe art doesn’t necessarily have to be a call to action or any other form of community service or alternative journalism. Art can be just for art’s sake. However, an exhibition is something that happens in the world. It doesn’t just offer my or other artists’ views and opinions about the shape of ideas and knowledge, but it demands a degree of responsibility as a public forum.

AM: How does the role of the curator, and in turn the exhibitions you conceive, help society reflect on its own position in the world: can art be too provocative?

CA: I don’t think there is such a thing as being too provocative. Provocation is a strategy that artists and curators use, some more successfully than others. You could say that our proposal for the Estonian pavilion is a provocative proposition to revisit the role of Estonia in world history, not only as a small nation under the yoke of the Soviet Union, but a country whose people had their own colonial ambitions, and achieved them in some cases. The subject of the pavilion is a very complex and layered project, and it is a learning process as well. We have been trying to navigate each other through the process, and have these discussions, as the pavilion is a collaborative one, and different voices and advisors are invited. Some provocations give us a deeper understanding of the invisible made visible, while others, which are careless in their approach, lack empathy, and can cause pain or harm to someone not understanding them. The two world crises, one, the pandemic, and the second, the current inhumane Russian-Ukrainian war, have shown how painful the world is already, and we need more humanity and more understanding between each other.

AM: How do you view your projects in relation to art history and the rapidly changing societies of the current time?

CA: Over the course of the last two centuries, the radical changes, from industrial to post-industrial modernity, technological to digital modernity, mass migration to the mass displacement of peoples, environmental disasters and genocidal conflicts, chaos and promise, have made fascinating subjects for artists. This situation is no less palpable today, when we are faced with such tremendous threats to our planet.

I see my projects as a basis for dense, restless and exploratory propositions spread across a multi-disciplinary field of references and artistic disciplines. I have kept this question in my projects: How can artists, thinkers, writers, composers, choreographers, singers and dancers, through images, objects, words, movements, actions, lyrics and sounds, bring the public together in active acts of engagement, looking, listening and speaking, to make sense of current tragedies? Along with artists and the public, and as a curator myself, I am not a neutral observer, but a protagonist in exhibitions and public projects.

Since I entered the field of art, I have not been interested in just curating, but in visual art and the history of art, and I see curating as an opportunity to make interventions where they are needed.

Kristaps Ancans Polar Rainbow Developed by Platvorm

AM: Apart from the Biennale, what would you say is the most interesting project you’ve worked on recently?

CA: I am currently working with the artist Kristaps Ancans on the AR sculpture Polar Rainbow. The sculpture was conceived by Kristaps as a tool of support and inspiration for communities and contexts where human rights, and in particular LGBTQIA+ rights, are under threat. Since I agreed to curate the project, we have worked closely to place the rainbow in particular locations, and to highlight the specific challenges when organisations that support communities are excluded or even criminalised. After launching the project in celebration of Pride Month in New York, which was received enthusiastically, we decided to position it in Eastern Europe. This was important for us, as we are both from the region: Kristaps is Latvian and I am Romanian by birth. To return to our roots, so to speak. We are well aware of the recent history of Poland’s so-called ‘LGBT-free zones’ where simply existing or living as a queer person is an act of defiance. We hope to attract attention to issues of intolerance and violence that still exist in Poland, and also in other EU countries that the rainbow crosses, such as Hungary and Romania. We have currently moved the rainbow over Qatar, which criminalises the LGBT community. Nonetheless, the World Cup is now being played there, and the rainbow symbol has been outright banned, while FIFA has forbidden players to display it. We have managed to show the rainbow there with the support of football fans and allies. This shows that, even in these challenging contexts, there is still a desire that things can and should be different, and that there are communities and organisations that offer protection and support.