Vsevolod Kovalevskij (b. 1988) is an artist-curator, living and working between Vilnius, Tromsø and Oslo. In 2020, he opened the artist-run space ‘InTheCloset’. He has participated in Rupert’s Alternative Education Programme in Vilnius (2014), holds a BFA and MFA from Vilnius Academy of Art (2015), and an MA from Tromsø Academy of Contemporary Art (2018) and Goldsmiths University (2018).

Aistė Marija Stankevičiūtė (AMS): If I were to put you in my head, you would probably take the form of a hydra, juggling with glowing pixels, words that rhyme before falling apart, and spaces teeming with creatures, some more familiar than others.

If you were to stay in human form, you would give the impression of being a perfect time planner, which is really a superpower, no less than the ability to manipulate multiple objects at once.

You are also an artist, a curator, and a creator of situations and communities, and I have no doubt that at the end of our conversation, these paragraphs will be filled with many new forms of yours.

I would like to start the conversation with your curatorial work. A couple of years ago in Tromsø, in a cupboard in your apartment, 350 kilometres north of the Arctic Circle, you opened an exhibition space called InTheCloset, for projects that question the meaning behind gender, identity, discomfort, censorship, inclusiveness, and the lack of it. While it’s not such a rare occurrence to run a gallery in one’s home, I rarely hear about an exhibition in a cupboard. It would be interesting to know how this space started. Which came first, the title or the space?

Vsevolod Kovalevskij (VK): What an impressively deep presentation, drawing parallels between interweaving mythologies, from Chronos to the multi-headed Hydra that changed depending on the place, the time and the imagination of the authors, an evolving creature, questioning the evolution of multi-universals.

You’re absolutely right that galleries in homes aren’t rare. That’s why for a long time I avoided thinking about opening a gallery at home. The emergence of the space happened subconsciously in 2019, when I moved into a new apartment. The title and the space did not follow each other, but my experience of being a person identifying as ‘queer’. When I arrived in Norway from Lithuania, where I was quite open about my orientation, I experienced a kind of cultural shock. For the first time since 2010, I encountered a lot of people who were still ‘in the closet’, and when asked why, they usually replied that coming out of the closet would be equal to social suicide. After hearing this from a large group of people, I was horrified. It is important to note that the first conversations with people in hiding happened in the relatively small town of Tromsø, which has a population of around 90,000. But even in bigger cities, including Oslo, I still got into weird situations. Since then, I have become interested in the history of Norwegian LGBTQIA+, and I was shocked to discover that homosexuality, for example, was only decriminalised fifty years ago. The first book on the history of Norwegian LGBT was published in 2019. In terms of the visual arts, the spaces that represent LGBT started their activities no earlier than 2012, and the last space that communicated on LGBT topics closed in 2021. There are many parallels between what I have seen in Lithuania and what I have experienced through stories in Norway. Being interested in the field of art and LGBTQIA+ representation, I missed art that reflected and raised questions about this socio-cultural section of society. As a result, InTheCloset emerged as a kind of space that basically dared to speak out, inviting people into an intimate space. It has become a safe space for dialogue, not only between art objects and visitors, but also directly between the visitor and the artist. It is also important to mention that the understanding of ‘queer’ in Norway is rather superficial. The Queer community is quite small, even in Oslo, and the concept of ‘queer’ is isolated, for example, from political ideology.

Vsevolod Kovalevskij

AMS: Hiding in a cupboard seems to make you feel like the monster that you involuntarily learn to fear as a child, and that anxiety doesn’t leave you, even when you start living alone, paying taxes, and having troubled sleep. In these cases, the only way out is probably to form monster communities that whisper in the shadows first, and then pop out into society in all their colours. We are used to thinking that what happens in intimate spaces usually stays there for ever. What role do you think InTheCloset plays in this context? Would you agree that by organising events at home, a place to which we usually invite people who we trust completely, you narrow your audience down to a small circle? It is interesting to think who InTheCloset is aimed at, and who participates in it?

VK: I would agree with your statement that we usually invite people into our home who we trust completely, but not in the case of InTheCloset. Most visitors are strangers, since communication about the gallery’s existence spread by word of mouth, so eventually quite a lot of people, not just people close to me, learned about the possibility to experience what it means to hide in the closet. However, a visitor cannot come to InTheCloset whenever they want, it is only by agreement. A visit can last up to twenty-five minutes, and the maximum number of people in the closet during the agreed time is two. So one of the more curious situations was when eight guests from Italy requested to come at the same time.

The experience of inviting strangers into my home is not so unacceptable to me personally, because it opens up opportunities for new connections, conversations, and even friendships; it shapes the community, in local, national and global contexts. The fact that somewhere in the city, in someone’s bedroom, and even more so in a cupboard, there is a gallery, seems shocking and intriguing to strangers who come. I think it’s the visitor who experiences a bigger shock in this case, because arriving at someone’s house, entering their bedroom and the cupboard, where they are locked for twenty-five minutes, is really an adventure. For some people, twenty-five minutes feel like hours, and sometimes visitors leave the cupboard with tears in their eyes.

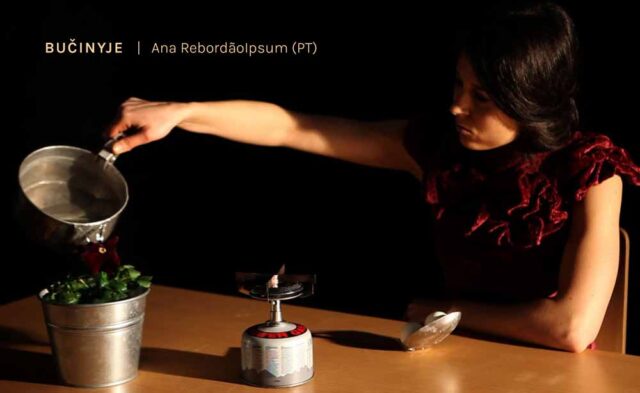

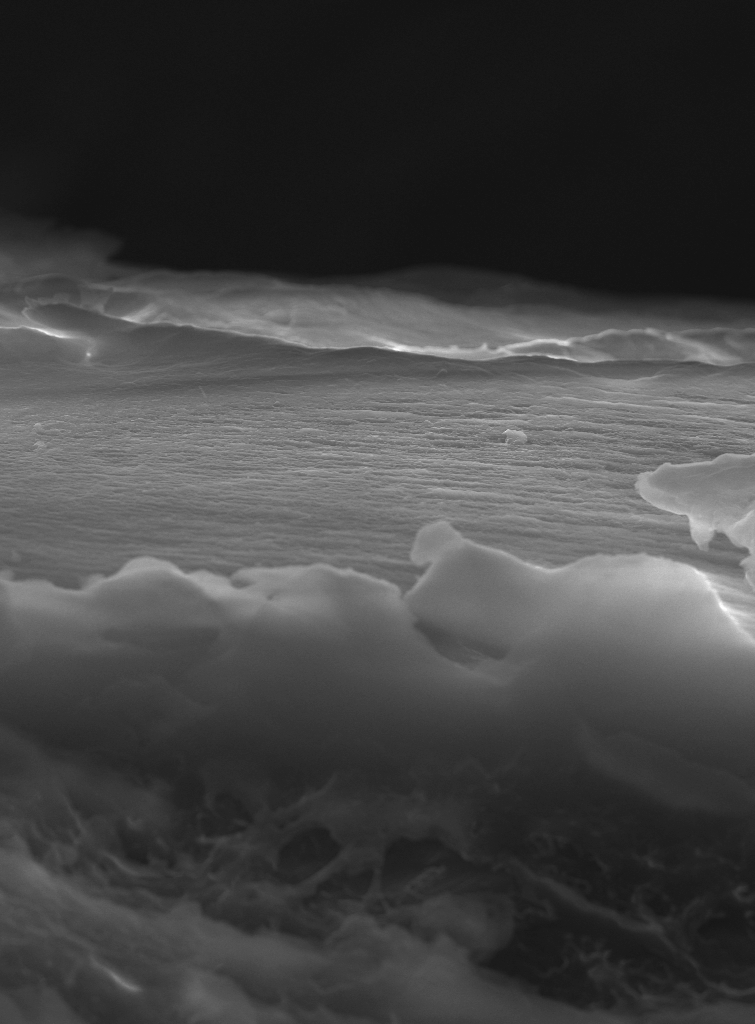

Talking of skeletons in cupboards, I think we should expand. We don’t just keep skeletons in cupboards. We have all possible worlds in there, our secrets, our experiences, and so on. InTheCloset has two functions in this context: it’s a place where artworks create new spaces and sensations. For example, the film Now and There, Here and Then (2018) by the South Korean artist Sun Park, depicting a conversation between her mother in South Korea and the artist herself living in the United Kingdom, reflects on the role of women, cultural differences, and themes of loneliness. The Belgian artist Anouk De Clercq, meanwhile, examines the surface of a single frame from a sixteen-millimetre black-and-white film with a microscope, reflecting on ways of seeing and the nature of cinema. Spatiality is one of the key concepts in Anouk De Clercq’s work, where she delves into space as deeply as possible, on the smallest scale, and tries to see what insights we can get from this other perspective. In the context of InTheCloset, the work suggested reflecting on the invisible history of LGBTQIA+ cinema. Rebecka Erin Moran’s ‘Pleasure Altar’, in collaboration with SmellLab Berlin (a scent studio) and the sound designer Kristján Zaklynsky, created a ‘masturbation chamber’, filled with butt-plug-shaped organic wax candles scented with specially designed perfume that lulled the visitor into a trance, while listening to the techno feminist soundtrack ‘Stop Stopping Now Hypnosis’.

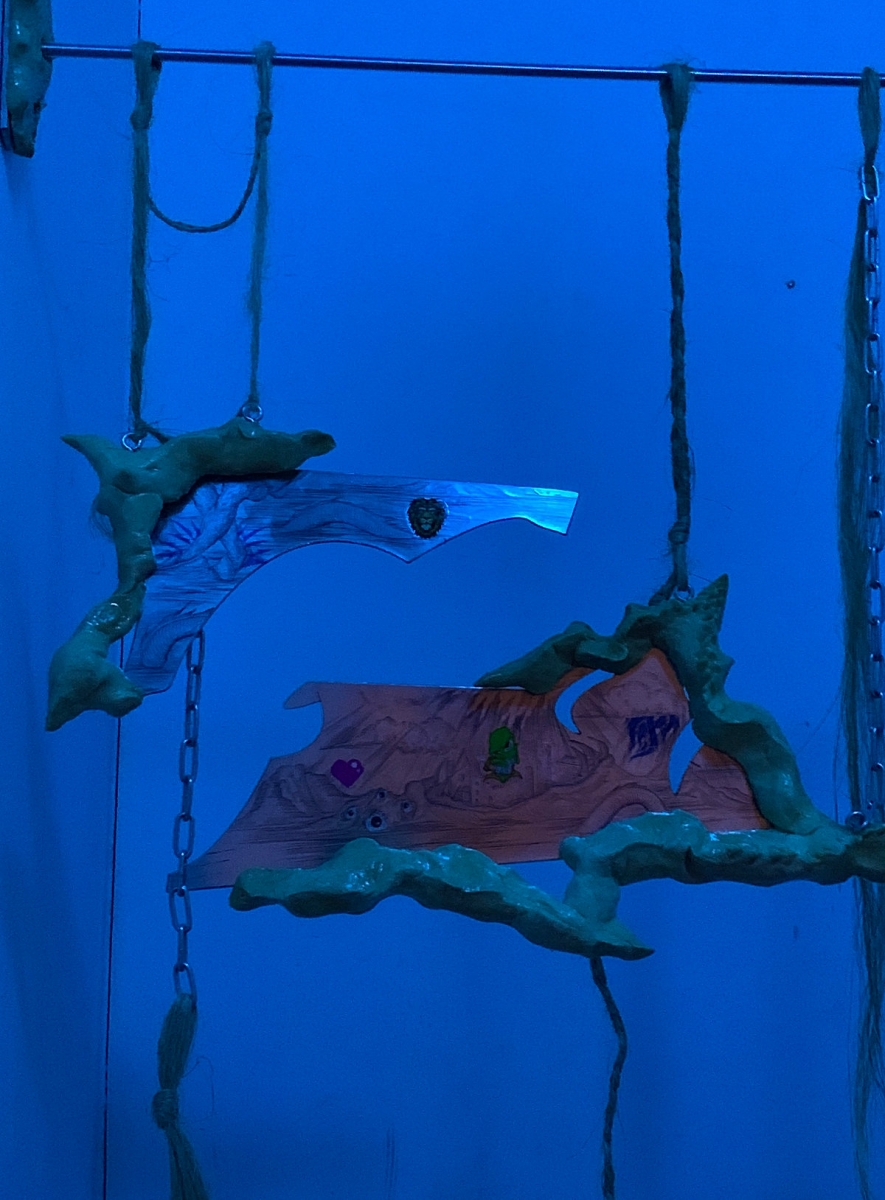

Thinking directly about monsters and communities, I’d like to mention Anastasia Sosunova and her series ‘Metallic Taste in Your Mouth’, inspired by East European festive korovai cakes, used as a gesture of family or community acceptance in traditional rituals such as weddings. Sosunova bakes korovai cakes her own way: she reveals metal cores with horrific etchings and apocalyptic images. By engraving hybrid creatures and diluvial landscapes, the artist tries to find refuge in the spheres of the excommunicated. Monstrosity here appears as a force of liberation from tradition and normality, and points to an alternative. In this sense, as Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri suggest, ‘We can acknowledge these monstrous metamorphoses of the body not only as danger but also as an opportunity to create an alternative society.’

And finally, the second function of InTheCloset is a dialogue between a work of art, a space, a visitor, an experience, an artist, a curator, and ultimately, the broader context that takes place outside the closet.

Anne Haaning, Search Quarry, installation view, InTheCloset, Tromsø

AMS: Is it true that there are two closets, in Tromsø and Oslo? Can you tell us how the second one came about?

VK: The presence of InTheCloset really depends on where I live, which depends on my mood in which country I want to be at the time and the obligations I have. The location of the space also depends on whether the apartment has a space for InTheCloset. Therefore, there is always only one closet. This creates ‘living’ migrating spaces, with their unique challenges and experiences. In this case, it involves not only the architectural, domestic and social (rent, flatmates, etc) circumstances, but also local issues relating to both the city in which the space is located and national and international political issues. The relocation from Tromsø to Oslo, for example, completely changed the architecture of the space, and created additional tasks in preparing the exhibition programme, because it had to be coordinated with the leisure time of my flatmates, which, for example, was not an issue in Tromsø. There are also questions about differences and similarities in the social and historical context, such as Tromsø and Oslo, and northern and southern Norway. This creates a difference between artists and their projects in the programme. The main task of InTheCloset is to show art projects that are not shown enough, or to expand already-existing dialogues.

AMS: It would be interesting to hear about your life with your works. After all, even when you’re alone, you’re not alone, and something is constantly showing in your cupboard. I’m not sure if I’d be able to concentrate in those circumstances; maybe it would only work if I imagined that the art only existed for as long as I was looking at it. On the other hand, since you yourself are the organiser of the space, you have a great opportunity to invite only the works that you agree with, because you will have to live with them for a bit as well. Do you ever choose projects that provoke you (or your flatmates)?

VK: I can’t imagine my life without art. The constant updating of artworks is a privilege that makes me improve, not only as an artist and curator, but also as a person. It really happens that I choose projects that provoke not only me but others as well. If I chose only what I like, I wouldn’t be able to escape a kind of bubble/closet, and end up not having anything to communicate or discuss. An empty discussion only leads to empty experience, and we have enough of that already. Provocations and misunderstandings are important to our development. When choosing artists whose work I do not necessarily understand at the beginning, I reflect on it with each review and each conversation. A great example would be Edvine Larssen’s ‘Not Worth While. Textbulbs #IV’. It’s a work that is special with its simplicity and multi-layered nature. The project began in 2001, when the artist was living in London. At the time, Edvine was interested in the incandescent light bulb as a poetic space. The artist began sandblasting bulbs to write a text on the glass surface. This is a particularly delicate process, which requires time. Extracts from the text are taken from Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (1952). The play reflects on uncertain futures and the uneasiness that perfectly portray the present world. The fourth version of the work shown in InTheCloset (Oslo) consisted of four incandescent bulbs, engraved with the sentences: ‘Not worthwhile, now’ and ‘[Silence]’. After seeing the work, my flatmates asked what four lightbulbs can say, and why it is a work of art. We discussed it in topics ranging from self-harm and suicide, to the illusory world we live in. In this way, questions about why this is presented as a work of art, and what impact and dialogue it can communicate, were answered.

AMS: I was moved by your thoughts about the hollow experience that arises from living in a bubble, where there’s nothing to talk about, because everything is great. But how nice it is when someone stands on your toe! This is how the deepest conversations begin sometimes. What other activities, without running InTheCloset, do you spend your time on?

VK: Exactly, when everything is ‘great’, for me, personally, is one of the worst experiences, which reminds me of Tegan and Sara along with The Lonely Island song ‘Everything is AWESOME!!!’. And my activities outside the cupboard, preparing for solo and group exhibitions, working with multi-channel audio installations and photograph series, re-editing the WashUpWashDown movie, and developing a collection of clothes and accessories. I’m working on compiling and distributing an archive of exhibitions and curated projects together with the Norwegian Association of Curators, developing strategies and guidelines considering the position and responsibilities of the curator, and how to introduce a ‘safety catch’ when working as a freelance curator. There is a very intense debate going on about this topic in Norway. I develop projects for my PhD, read books, go to exhibitions and the cinema. Most of all, I develop my culinary and gourmet skills.

AMS: Cool! Can you tell us more about the development of the collection?

VK: The development of the collection is a very exciting field of new experience, in terms of scale and audience. It’s an intense process that requires reflecting on endless scenarios, boredom leading to pragmatic financial decisions, and, most importantly, considering environmental issues. However, the creative side of development is extremely interesting, and has parallels between everyday creation: the testing, prototyping and selection of materials, design solutions, search for shapes, and communication with craftsmen. For now, I can only share such details about this new activity.

AMS: Perhaps to finish our conversation, you might share what exhibitions or events await you in the near future?

VK: Probably, like everyone, I look forward to visiting documenta fifteen, to experience the subtleties of ruangrupa collective curating. And in the coming weeks, I really want to visit Sandra Mujinga’s newly opened exhibition at the Munch Museum, and together with the Norwegian artist Lars Laumann, we will travel to document the spaces for the work he will present for InTheCloset in March. I’m also looking forward to Dora García’s screenings of Love with Obstacles and If I Could Wish for Something. And while in Lithuania in the coming weeks, I will visit the artists’ studios Sodas2123, and hope to visit recently opened exhibitions in Vilnius and Kaunas. So, I hope to meet many friends and strangers whom I miss.

Not worth while (Textbulbs # IV) 2021. Edvine Larssen, exhibition view, InTheCloset, Oslo

Not worth while (Textbulbs # IV) 2021. Edvine Larssen, exhibition view, InTheCloset, Oslo

Anne Haaning, Search Quarry, installation view, InTheCloset, Tromsø

Atlas, 2016, Anouk De Clecq, exhibition view, InTheCloset, Tromsø

Atlas, 2016, Anouk De Clecq, video still

Metallic Taste in Your Mouth, 2020 – 2021, Anastasia Sosunova, exhibition view, InTheCloset, Tromsø

Metallic Taste in Your Mouth, 2020 – 2021, Anastasia Sosunova, exhibition view, InTheCloset, Tromsø