Linda Boļšakova is a Latvian interdisciplinary artist, who uses a myriad of artistic and critical instruments in her work to address the question of the relationship between humans and other species in the ecosystem. This relationship is seen as being biologically determined, and yet also something that is always in the making: unfixed and fluctuating. The artist emphasises that she sees her work as poetry that poses unanswered questions and opens up a space for communication, but is also positive and encouraging, and not preaching. Although her works are often complex and sculptural, performance is the main medium, which often serves as a channel for dialogic engagement with audiences.

Laine Kristberga: Can you tell us a little bit more about your interest in biological processes and art? How do you find the points of intersection between these two disciplines?

Linda Boļšakova: The subject of plants is very close important to me. I started working on this topic while I was studying in Scotland. Over time, I have introduced slight transformations, but I am still working on it today. I am interested not only in the relationship that people have with plants, which is a very interesting topic, rich in opportunities for exploration, but the bonds as such. And, of course, since we are all experiencing the pandemic, the question of bonds and relationships has become even more relevant.

LK: Have you carried out extensive research in this field? Are there authors whose work is especially important to you?

LB: Timothy Morton, and his book Dark Ecology [2016]. I read it for research purposes, but it turned out to be important to me personally, too. Also, Donna Haraway. I think everyone is quoting her [laughs] I also find Timo Maran’s book Ecosemiotics very valuable. It inspired the linguistic aspect of the ‘Seed Library’ project at the ‘Sporta Pils’ urban gardening project, which consists of stories that I collected from the ‘Sporta Pils’ gardeners. My aim was not to collect stories where gardeners express their pride in growing the most outstanding vegetables or flowers, but stories of ordinary routines, where gardeners went to a supermarket, bought some seeds or plants that were for sale, and then forgot to water them, and nothing came of it. This experience is also valuable, because it all reveals our relationship with plants and the environment, especially in an urban environment. The gardeners usually replied that they had nothing special to say, but when I heard the stories, they were full of valuable insights, and very touching, amusing and diverse. I really enjoyed working with the gardeners and listening to their stories! You can listen to these stories on the ‘Sporta pils dārzi’ website (https://sportapilsdarzi.lv/lv/stories). The project echoes Timo Maran’s ideas in terms of the language we use to speak with and about plants, Ursula K. Le Guinn’s story of phytolinguists, and Michael Marder’s invitation to grow botany of words, and Robin Wall Kimmerer’s emphatic way to learn from plants. Language is very often criticised for being a system full of dichotomies. This project is a modest attempt, together with gardeners, to develop a language that doesn’t just describe plants, but has grown from them. A common language that might assist us in understanding them better. It is, of course, hard to say how much we can actually succeed in this, and how feasible it is to ever understand the Other. Nevertheless, I believe it is worth attempting, and seeing what comes of it.

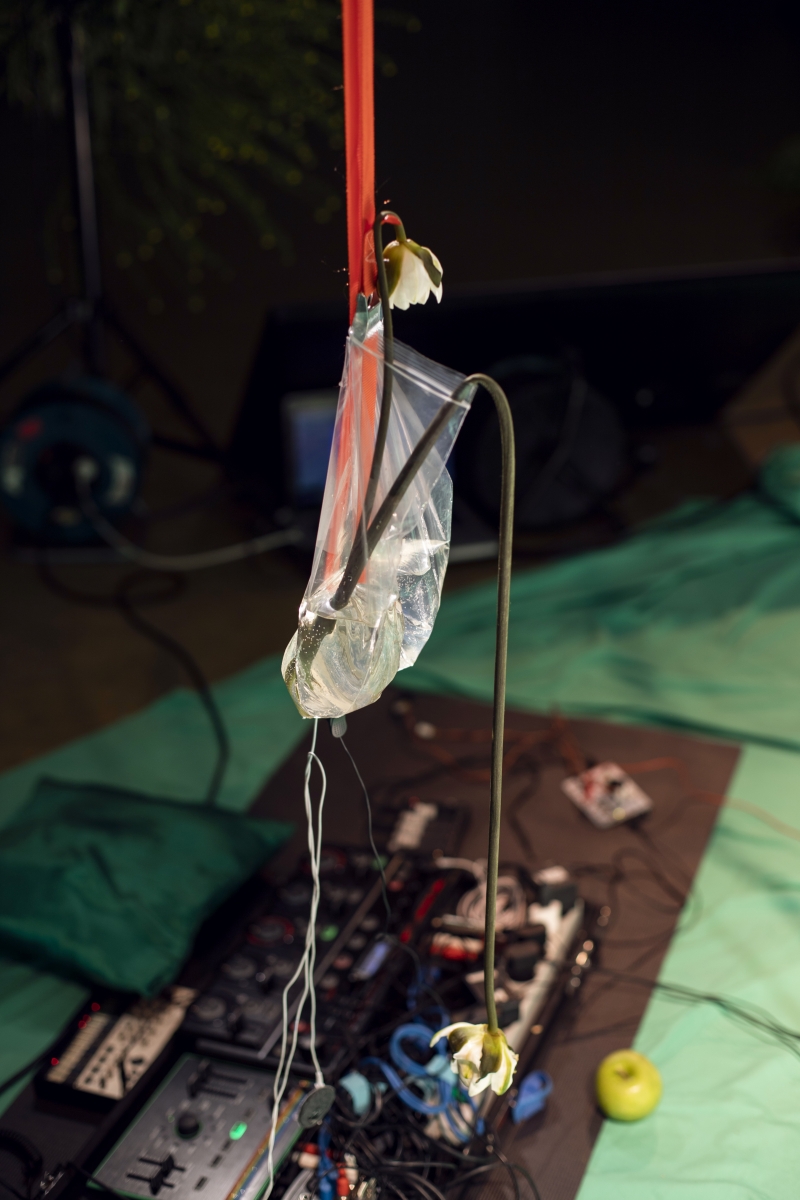

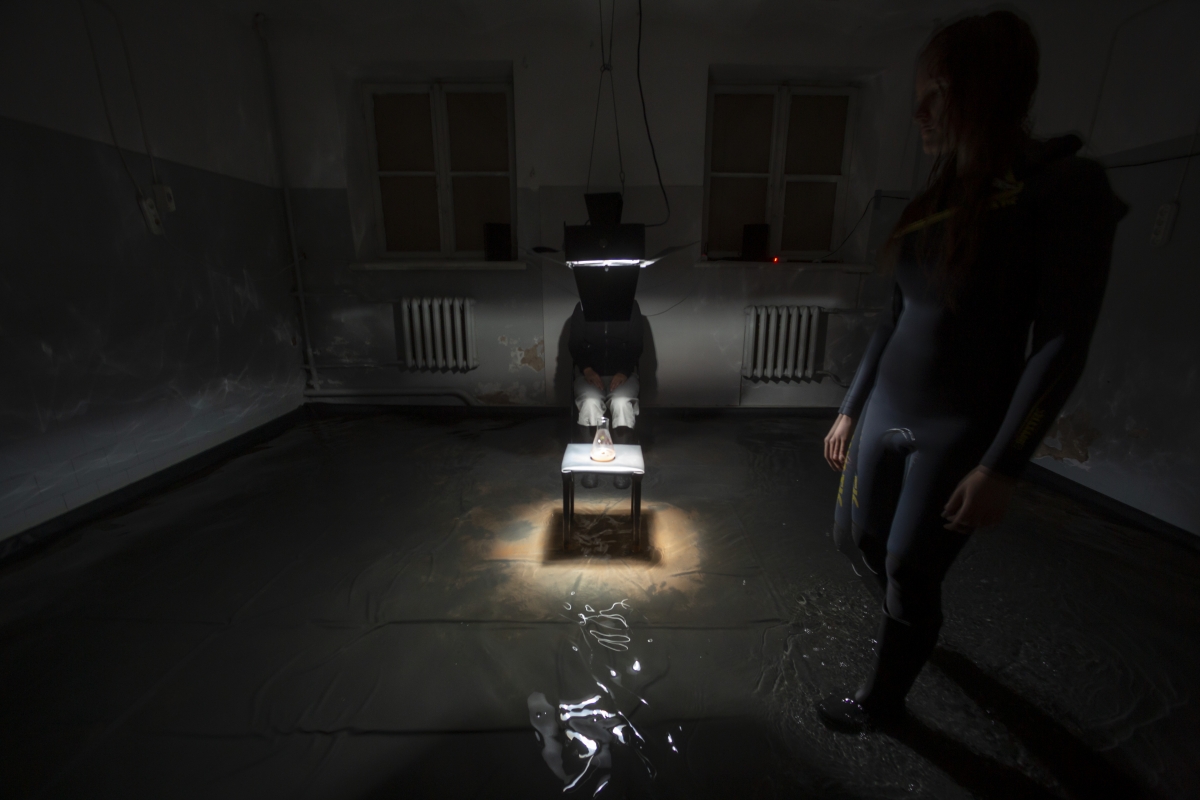

Living Memory. Multisensory experience for one person. Part of the cycle of events “Ecosystems of Change” (Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, curated by Ieva Astahovska), 2021. Photos by Didzis Grodzs.

LK: How is it being an artist who is interested in plants? Is it difficult to find like-minded artists in Latvia? Or do you feel rather isolated, because there is no network?

LB: Yes, I’m often in touch with my former fellow-students from Scotland, who have moved to Finland or elsewhere. Also, the artist Sandra Kosorotova from Estonia, who works with similar topics. Although there are many artists engaging with plant life in Latvia, I have somehow mostly collaborated with researchers.

LK: Have you had interdisciplinary projects as well? I mean projects where you collaborated with researchers?

LB: Yes, the ‘Seminafuturi’ project (https://seminafuturi.com/en/) is like that. It’s a series. We have a second seed already. The first was in Latvia, and is now located at the National Botanic Garden in Salaspils. The second seed is in the Nezahat Gökyiğit Botanic Garden in Istanbul in Turkey. These projects came to light in cooperation with researchers, a composer of music, a 3-D artist, and a web developer. It was very interesting. The work was like a point of intersections for various disciplines, as well as for plants and people. The process was about the coexistence of humans and plants in the future, and grew out of research into seed banks. I love putting various disciplines together. Coming back to the theme of language, they all have a certain language, a form of expression, or an artistic dialect, that enrich each other in the process of making. I find it really echoes this need for diversity, not only in nature but also in our practices.

LK: You are an interdisciplinary artist who often works with performative instruments. You frequently integrate your body into a work of art. You also create various models of interaction between you and the spectators. Can you comment on this creative strategy?

LB: Performance is one of the means of expression in my artistic practice. Along with installations and sculptural manifestations, a little bit of photography, and text as well. The body is crucial to me when thinking about modes of being and existing, as well as the relationship with the world of plants. I think the body is the key channel through which we can find a bond with plants. The bond that I would like to propose is one of equality between plants and human beings, and through corporeal co-existence, embodiment, I can create a non-hierarchical space where I’m not superior but equal to the plant. To just simply be and (co)exist is already powerful enough for me. Sometimes, when I see people come into an installation space full of rubble and weeds, it seems they don’t find anything worth seeing. For me, it invites a critical reflection in terms of our value systems, what we consider valuable or worth preserving at all. If something just exists, isn’t that valuable in itself? This also raises questions about our knowledge systems, and how much we understand the intricate connections of life networks. Even the tiniest element has its place, and is extremely valuable in the ecosystem. Perhaps this bond is invisible to us, but it does not mean that it doesn’t have any value.

LK: Can you tell us about the work Intimacy of Strangers (2020) at the ISSP Gallery?

LB: The gallery space was full of pollen. There was a specially created piece of music for the installation, and I invited people to dance. I was wearing a specially made velvet suit, created by Anastasija Golubeva, to echo the tactile aspect of the interaction. The performance was born in the mutual interaction between myself and the spectators, as well as the pollen and the music. What seemed valuable to me was the process of co-creation. I borrowed the title from the evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis, who characterised the process as the most fundamental practice of becoming with each other. The core of Margulis’ view of life is that new kinds of species evolve primarily through the long-lasting intimacy of strangers. One such example of the intimacy of strangers is the orchid and pollinator relationship, and this co-creative process extends to other realms as well.

Intimacy of Strangers. Installation and interactive performance. ISSP Gallery, 2020. Photos by Andrejs Strokins, Ingus Bajārs.

Intimacy of Strangers. Installation and interactive performance. ISSP Gallery, 2020. Photos by Andrejs Strokins, Ingus Bajārs.

LK: What were the reactions of the spectators? Did you instruct them, or rather implied what was expected of them?

LB: At first, people were impressed with the pollen and the smell of it. Sometimes people asked for explanations. So the experience usually started with a conversation. I told them about the work and the concept behind the piece. Margulis quotes the example of orchids and pollinators, namely, that orchids keep and embody the memory of the pollinator even after the pollinator has become extinct. When we look at orchids, we don’t usually think about certain species of bee, whereas the drone ‘sees’ the difference, and in a way engages in a playful dance with the flower. After telling the story, I then asked the spectators to dance with me [laughs] Each dance was different, and so was each performance piece. Some dances didn’t even involve touching, just movements of the hands and fingers. Others had several people moving together as one organism. Dancing with children was a completely different experience again.

LK: The spectator becomes a co-creator engaged in a work of art as a process. This is very characteristic of performance art. As a result, a more dynamic model of art consumption emerges.

LB: Definitely! The spectator becomes a creator of the experience too. The process is also essential. Although they are created materially before a show, my works are often activated at the moment when the spectator literally walks into the space. The creative process really starts when the exhibition opens. I sometimes envy photographers, for example, who can hang their work on the walls and go home [laughs] My work is often created in the interaction with the spectator, which is also very important when we think about the bonds and ecology.

LK: If we return to the question of biological connections from various perspectives, can you tell us about the work Off Spring that was exhibited at the Alma gallery (14 December 2019 to 17 January 2020) on Tērbatas Street in Riga? I remember its beautiful smell: peat and spring flowers.

LB: This work stemmed from a performance piece that I created for the performance event Springification organised at the Latvian Centre for Performance Art. In Off Spring, I was sleeping on peat, which filled the entire gallery from one end to the other. There was a slope, which also created a feeling of unbalance. I was sleeping there among spring flowers, hyacinths and snowdrops, which were growing slowly. The show opened on 13 December, but the gallery was full of spring. I thought, what it would be like if the spring started on 13 December? I was inspired by the poem ‘Primavera’ by the Scottish poet Robin Robertson about the movement of the seasons, that every new season comes as fast as we walk, at approximately the same tempo. Then I did a little calculation, and discovered that if people continue the same way, in 280 years, or sooner, spring could actually arrive on 13 December.

LK: This was a work created for viewing. Since the gallery is made of glass, accidental spectators, passers-by on the street, also had access to the work.

LB: Yes, I did not see them, because I was asleep, but I was told that a lot of passers-by stopped beside the gallery and watched me. There was also a contrast between the winter outside and me sleeping inside, in an environment so reminiscent of spring. Because I only had a tiny costume on, my body created a feeling of vulnerability and fragility.

LK: I hope it was warm indoors!

LB: Yes, it was rather warm, but when you sleep for hours on peat, at some point you start feeling the cold, and wish you could stand up and put on a coat [laughs] But I couldn’t do that! There was also a sense of equality with the plants, because they cannot walk away if they don’t like something in the environment. The only solution for them is to adapt. I became aware of it only in the process of performing. Since this work, I have really turned to this philosophy of process and time, where I contemplate important questions, and arrive at revelatory eureka moments through the process.

Off Spring. Installation and performance. Alma Gallery, 2019. Photos by Toms Harjo.

LK: Are you also thinking in the direction of eco-criticism, especially in terms of what the result of our action or lack of action is in the ecosystem?

LB: I do think about it, but I don’t want to become an evangelist who preaches and tells others how to lead their lives. I think about it personally, because I study the reciprocal relationship between plants and humans. Along with the climate crisis, this relationship has become more crucial. But I would rather abstain from defining my work as being based on eco-criticism. I hope to encourage relationship building between humans and plants, but it is entirely up to each individual what kind of relationship they want. I agree that it is valid to realise the current dynamic, but it is also important to understand how we can move on, to offer a way to imagine our relationship with plants being otherwise. I think that imagination and art are crucial and very important catalysts for change, and in this way art plays an important role in the climate crisis discourse. So what I want to emphasise in my work is the power of nature, its strength, rather than victimising it. I would like to encourage closer ties with the environment, as opposed to arguing that we are the ones to blame. We are not different; we are part of nature. Instead of eco-criticism, I see my works as being more aligned with poetry. The works are not didactic, but rather open up the possibility to question reality.

LK: Can you say a bit more about the challenges that you face when dealing with the ephemeral quality of your works. They often have a complex structure, they are meant to be experienced through various senses, and yet it is impossible to take them home and hang them on a wall. That, of course, would only be possible with the documentation.

LB: My works are always site-specific. They are connected to the space, and grow out of the specific environment where they are created. And in this sense, it is very difficult to adapt them to some other space and time, such as audio-visual space. In that case, they would be completely different works. For example, Off Spring would not work if it was created in the spring or the summer! It had to be exhibited on 13 December! [laughs] To some degree, this spatial-temporal quality is characteristic of all of my work, and I appreciate that very much. I see parallels with the cyclical patterns in nature, and that nothing is permanent. My works grow out of the environment where they are located; it is very similar to the world of plants.

LK: Are you planning to retain the performative instruments in your works? Does it feel natural to you?

LB: Yes, it feels very organic to me. I see performance as a part of the creative process, along with issues of materiality and embodiment. For example, in the project ‘Semina Futuri’ there was a completely different concept of embodiment and performance, since it was implemented in an augmented reality; however, it was still there.

Living Memory. Multisensory experience for one person. Part of the cycle of events “Ecosystems of Change” (Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, curated by Ieva Astahovska), 2021. Photos by Didzis Grodzs.

LK: Could you say a bit more about the project ‘Living Memory’ (2021), curated by Ieva Astahovska at the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art as part of the ‘Eco-Systems of Change’ series of events?

LB: This work reflected on the role of memory in society, and the importance of place in the preservation of memory. The research and learning process were focused on alpine butterwort (Pinguicula alpina), which has been extinct in Latvia since 2008. Its last natural growth was on the north side of the Staburags Cliff, which was flooded in 1965 by Soviet engineering work and the construction of a hydroelectric power plant. This plant currently grows only in sterile in-vitro lab conditions at the National Botanic Garden, despite the fact that the species had a natural habitat in Latvia since the last Ice Age (about 14,000 years ago)! It seems almost tragi-comic and absurd that something like this can happen! The genetic information stored by the plant for thousands of years has simply disappeared! And here we can see parallels with humans who saw the Staburags Cliff in their childhood and who still remember it. But such people are very few. When they pass away, there will be no living memory, just photographs and scientific facts. The memory will cease to live. ‘Living Memory’ was a multi-sensory experience for one person that encouraged us to think about these processes.

LK: Yes, Staburags was definitely a huge loss, which occurred due to the Soviet aim to create large-scale technology projects. But for Latvia, it had a symbolic value too. It was almost a part of the national identity.

LB: Yes, it was a very valuable and unique site, but it was also more than that. It was also meaningful because it was so important to people. It’s similar to the cemetery culture, where we go to the cemetery to remember the deceased and reflect on mortality and other issues. The site becomes meaningful because of the ritualistic and symbolic value. When such a site is lost, what do we do, and where do we go? I also think Soviet experiences and memories have not been processed enough. In this context, the work of art becomes a point of departure, which, I hope, allows us to address these issues. When people spoke about their experience of ‘Living Memory’, they spoke about an overwhelming sadness.

LK: In terms of media employed and public engagement, the work Angiosperm, which you created for the Riga Performance Festival ‘Starptelpa’ in 2019, is also worth mentioning. In this performance, you collaborated with the artist Sabīne Moore.

LB: Sabīne was amazing! In the performance, there was not only public but also technological engagement of the green screen, television and the medium of video where my live performance was transposed. Also, in the work, I addressed the question of sexuality: I see it as being intrinsically connected with our human nature in terms of creation and life. And, as such, I think we should appreciate and respect it. We should also view it critically as something that has become an integral part of consumer culture. I also think that female sexuality is rather problematic, at least that’s how I feel. I’m interested in the topic of sexuality and eco-sexuality, how sexuality is manifested in the world of plants.

LK: Can you explain the concept of eco-sexuality?

LB: Eco-sexuality emerged as a critical discourse in which the idea and assumption that nature should be perceived as a forever-giving and forever-forgiving mother is criticised. Eco-sexuals claim that it would be healthier to perceive nature as a lover, as opposed to a mother, because a lover will not forgive you for your wrongdoings [laughs]. Eco-sexuality encourages a love of nature and an intimacy-based relationship that we experience when we are in nature, for example, when we swim or enjoy being outdoors. The movement was started by Annie Sprinkle and her partner Beth Stephens. They have also created performances where they marry various natural entities. In the film festival ‘2ANNAS’, I curated a programme of short films dedicated to eco-sexuality.

LK: What project are you working on at the moment?

I’m currently working on a continuation of the ‘Living Memory’ project for an exhibition at the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art at the end of this year. There are plans to plant alpine butterwort (Pinguicula alpina) at the Staburags Cliff of Rauna this year, so it will be exciting to see this little carnivorous plant growing in Latvia again.

Angiosperm. Performance at Riga Performance Art Festival “Starptelpa” (Latvian Centre for Performance Art), 2019. Photos by Anna Maskava.

Angiosperm. Performance at Riga Performance Art Festival “Starptelpa” (Latvian Centre for Performance Art), 2019. Photos by Anna Maskava.

Angiosperm. Performance at Riga Performance Art Festival “Starptelpa” (Latvian Centre for Performance Art), 2019. Photos by Anna Maskava.

Angiosperm. Performance at Riga Performance Art Festival “Starptelpa” (Latvian Centre for Performance Art), 2019. Photos by Anna Maskava.

Intimacy of Strangers. Installation and interactive performance. ISSP Gallery, 2020. Photos by Andrejs Strokins, Ingus Bajārs.

Intimacy of Strangers. Installation and interactive performance. ISSP Gallery, 2020. Photos by Andrejs Strokins, Ingus Bajārs.

Intimacy of Strangers. Installation and interactive performance. ISSP Gallery, 2020. Photos by Andrejs Strokins, Ingus Bajārs.

Intimacy of Strangers. Installation and interactive performance. ISSP Gallery, 2020. Photos by Andrejs Strokins, Ingus Bajārs.

Living Memory. Multisensory experience for one person. Part of the cycle of events “Ecosystems of Change” (Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, curated by Ieva Astahovska), 2021. Photos by Didzis Grodzs.

Living Memory. Multisensory experience for one person. Part of the cycle of events “Ecosystems of Change” (Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, curated by Ieva Astahovska), 2021. Photos by Didzis Grodzs.

Living Memory. Multisensory experience for one person. Part of the cycle of events “Ecosystems of Change” (Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, curated by Ieva Astahovska), 2021. Photos by Didzis Grodzs.

Living Memory. Multisensory experience for one person. Part of the cycle of events “Ecosystems of Change” (Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, curated by Ieva Astahovska), 2021. Photos by Didzis Grodzs.

Living Memory. Multisensory experience for one person. Part of the cycle of events “Ecosystems of Change” (Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, curated by Ieva Astahovska), 2021. Photos by Didzis Grodzs.

Living Memory. Multisensory experience for one person. Part of the cycle of events “Ecosystems of Change” (Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, curated by Ieva Astahovska), 2021. Photos by Didzis Grodzs.

Off Spring. Installation and performance. Alma Gallery, 2019. Photos by Toms Harjo.

Off Spring. Installation and performance. Alma Gallery, 2019. Photos by Toms Harjo.

Off Spring. Installation and performance. Alma Gallery, 2019. Photos by Toms Harjo.

Off Spring. Installation and performance. Alma Gallery, 2019. Photos by Toms Harjo.

Semina futuri: placeholder for future coexistence (II Ophrys Lycia). AR performance, environmental sculpture, specially composed music, website and an exhibition at Depo, Istanbul, curated by Rana Öztürk. 2021. Work is part of Nezahat Gökyiğit Botanical Garden collection in Istanbul.

Seminafuturi1.1 : Semina futuri: placeholder for future coexistence (I Cypripedium calceolus). AR performance, environmental sculpture, specially composed music and website. Sculpture Quadrennial Riga, 2020. Work is part of the National Botanic Garden collection in Salaspils, Latvia.

Semina futuri: placeholder for future coexistence (II Ophrys Lycia). AR performance, environmental sculpture, specially composed music, website and an exhibition at Depo, Istanbul, curated by Rana Öztürk. 2021. Work is part of Nezahat Gökyiğit Botanical Garden collection in Istanbul.

Semina futuri: placeholder for future coexistence (II Ophrys Lycia). AR performance, environmental sculpture, specially composed music, website and an exhibition at Depo, Istanbul, curated by Rana Öztürk. 2021. Work is part of Nezahat Gökyiğit Botanical Garden collection in Istanbul.